A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emmett Till-‐ the Murder That Sparked the Civil Rights Movement Emmitt Till

Emmett Till- The Murder that sparked the Civil Rights Movement Emmitt Till Travel Exhibit on display in classroom. Day 1- Students will watch The PBS documentary on the Murder of Emmett Till And students will keep a journal of key events, locations, and people related to this historical event. Day 2-Guest Speaker Lent Rice- Current Director Bureau of Professional Standards of the Desoto Sheriff’s Department. Lived in Sumner Mississippi when the Emmett Till murder trial occurred and was on the FBI investigation team to reopen the Emmett Till Murder case in 2006. Students will watch videos of Wheeler Parker and Simeon Wright ( from the Delta Center Archives ) share what happened in the store , the night Emmett Till was kidnapped, and the murder trial. Students will have copies of The Court Reporter activities from the Delta Center and complete the student activities on the Emmett Till traveling exhibit. Day 3- Primary Source – students will be provided with a copy of the lyrics to the Bob Dylan song, the murder of Emmett Till, and follow along as they listen to Bob Dylan perform the song. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVKTx9YlKls DAY 3 – Students in small groups will be provided with articles from the Mississippi History Archives on Acts of Civil disobedience in Mississippi. and must write and perform their own Protest Song based on one of the historical events. (This lesson plan is available on the website the Mississippi Department of Archives and History) Day 4- Student groups will perform protest songs in class. Awards will be granted to best performance and best song. -

Marching Through '64

MARCHING THROUGH '64 David J. Garrow Wilson Quarterly Spring 1998, Volume 22, pp. 98-101. Section: Current Books PILLAR OF FIRE: America in the King Years, 1963-65. By Taylor Branch. Simon & Schuster. 746 pp. $30 Pillar of Fire is the second volume of Taylor Branch's projected threevolume history of the American black freedom struggle during the 1950s and 1960s. Ten years ago, Branch published his first volume, Parting the Waters, a richly detailed account of the civil rights movement that covered the years 1954-63 in 922 pages of text. Ending with the aftermath of John F. Kennedy's November 22 assassination, Parting the Waters was intended to be the first of two volumes that would carry the story forward until Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination on April 4, 1968. But Branch changed plans, expanding his history from two volumes to three. Pillar of Fire covers the movement's history from December 1963 until February 1965 in 613 pages of text. Or, to be more precise, about 419 pages of text, for the first 194 pages are devoted to recapitulating much of the 1962-63 history that the author comprehensively treated in Parting the Waters. Should Pillar of Fire be evaluated by itself, or should it be assessed in tandem with Parting the Waters? As King often said, most "either-or" questions-this one included-are best answered with "bothand" responses. Comparing Pillar with Parting raises two questions: why devote almost one-third of Pillar to a reprise of Parting, and why allocate 400-plus pages to essentially just 1964, when all of 1954 through 1963 merited "only" 900? In the author's defense, his readers- whether or not they read Parting the Waters a decade ago-deserve some recapitulation, and 1963 and 1964 almost inarguably were the crucial years of the civil rights movement. -

Hamer Biography

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977) “All my life I’ve been sick and tired. Now I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” Fannie Lou Hamer was among the most significant participants in the struggle launched in the latter half of the twentieth century to achieve freedom and social justice for African Americans. Born October 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, Mississippi, she was the last of the twenty children of Lou Ella and James Townsend. They were sharecroppers, and since sharecropping generally bound workers to the land (a form of peonage), most sharecroppers were born poor, lived poor, and died poor. At age six Fannie Lou joined her parents in the cotton fields. By the time she was twelve, she was forced to drop out of school and work full time to help support her family. At age 27 she married another sharecropper named Perry “Pap” Hamer. In August 1962, Mrs. Hamer attended a meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in her hometown, Ruleville, Mississippi. This is where she made the fateful decision to attempt to register to vote. For this decision she was forced by her landlord to leave the plantation where she worked. In June the following year, she and several SNCC colleagues were brutally beaten in a Winona, Mississippi jail by law enforcement officers. This beating left her blind in her left eye and her kidneys permanently damaged. Mrs. Hamer’s historic presence in Atlantic City at the 1964 national convention of the Democratic Party brought national prominence with her electrifying testimony before the convention’s credentials committee. -

Remarks and a Question-And-Answer Session With

1092 July 17 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1997 but how we're going to become one America if I had a voice like that, I could run for in the 21st century. We need your help. a third term, even though theÐ[laughter]. In September, I'm going home to Little I enjoyed meeting with your board mem- Rock to observe the 40th anniversary of the bers and JoAnne Lyons Wooten, your execu- integration of Little Rock Central High tive director, backstage. I met Vanessa Wil- School. When those nine black children were liams, who said, ``You know, I'm the presi- escorted by armed troops on their first day dent-elect; have you got any advice for me of school, there were a lot of people who on being president?'' True story. I said, ``I were afraid to stand up for them. But the do. Always act like you know what you're local NAACP, led by my friend Daisy Bates, doing.'' [Laughter] stood up for them. I want to say to you, I'm delighted to be Today, every time we take a stand that ad- joined here tonight by a distinguished group vances the cause of equal opportunity and of people from our White House and from excellence in education, every time we do the administration, including the Secretary of something that really gives economic Labor, Alexis Herman, and the Secretary of empowerment to the dispossessed, every Education, Dick Riley, and a number of oth- time we further the cause of reconciliation ers from the White House. -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

Martin Luther King Jr.'S Mission and Its Meaning for America and the World

To the Mountaintop Martin Luther King Jr.’s Mission and Its Meaning for America and the World New Revised and Expanded Edition, 2018 Stewart Burns Cover and Photo Design Deborah Lee Schneer © 2018 by Stewart Burns CreateSpace, Charleston, South Carolina ISBN-13: 978-1985794450 ISBN-10: 1985794454 All Bob Fitch photos courtesy of Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, reproduced with permission Dedication For my dear friend Dorothy F. Cotton (1930-2018), charismatic singer, courageous leader of citizenship education and nonviolent direct action For Reverend Dr. James H. Cone (1936-2018), giant of American theology, architect of Black Liberation Theology, hero and mentor To the memory of the seventeen high school students and staff slain in the Valentine Day massacre, February 2018, in Parkland, Florida, and to their families and friends. And to the memory of all other schoolchildren murdered by American social violence. Also by Stewart Burns Social Movements of the 1960s: Searching for Democracy A People’s Charter: The Pursuit of Rights in America (coauthor) Papers of Martin Luther King Jr., vol 3: Birth of a New Age (lead editor) Daybreak of Freedom: Montgomery Bus Boycott (editor) To the Mountaintop: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Mission to Save America (1955-1968) American Messiah (screenplay) Cosmic Companionship: Spirit Stories by Martin Luther King Jr. (editor) We Will Stand Here Till We Die Contents Moving Forward 9 Book I: Mighty Stream (1955-1959) 15 Book II: Middle Passage (1960-1966) 174 Photo Gallery: MLK and SCLC 1966-1968 376 Book III: Crossing to Jerusalem (1967-1968) 391 Afterword 559 Notes 565 Index 618 Acknowledgments 639 About the Author 642 Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the preeminent Jewish theologian, introduced Martin Luther King Jr. -

Unwise and Untimely? (Publication of "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"), 1963

,, te!\1 ~~\\ ~ '"'l r'' ') • A Letter from Eight Alabama Clergymen ~ to Martin Luther J(ing Jr. and his reply to them on order and common sense, the law and ~.. · .. ,..., .. nonviolence • The following is the public statement directed to Martin My dear Fellow Clergymen, Luther King, Jr., by eight Alabama clergymen. While confined h ere in the Birmingham City Jail, I "We the ~ders igned clergymen are among those who, in January, 1ssued 'An Appeal for Law and Order and Com· came across your r ecent statement calling our present mon !)ense,' in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom, if ever, do We expressed understanding that honest convictions in I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts I sought to answer all of the criticisms that cross my but urged that decisions ot those courts should in the mean~ desk, my secretaries would he engaged in little else in time be peacefully obeyed. the course of the day, and I would have no time for "Since that time there had been some evidence of in constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of creased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Re genuine goodwill and your criticisms are sincerely set sponsible citizens have undertaken to work on various forth, I would like to answer your statement in what problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Bir I hope will he patient and reasonable terms. mingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and real I think I should give the reason for my being in Bir· istic approach to racial problems. -

LD5655.V855 1996.M385.Pdf (6.218Mb)

EDUCATING FOR FREEDOM: THE HIGHLANDER FOLK SCHOOL IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, 1954 TO 1964 by Jacqueline Weston McNulty Thesis submitted to the facutly of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History APPROVED: Yuu a Hayward Farrar, Chairman _ \ 4 A af 7 - “ : Lo f lA bn G UU. f Lake Ak Jo Peter Wallenstein Beverly Bunch-Ly ns February, 1996 Blacksburg, Virginia U,u LD 55S Y$55 199@ M2g5 c.2 EDUCATING FOR FREEDOM: THE HIGHLANDER FOLK SCHOOL IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, 1954 TO 1964 by Jacqueline Weston McNulty Dr. Hayward Farrar, Chairman History (ABSTRACT) This study explores how the Citizenship School Program of the Highlander Folk School shaped the grassroots leadership of the Civil Rights Movement. The thesis examines the role of citizenship education in the modern Civil Rights Movement and explores how educational efforts within the Movement enfranchised and empowered a segment of Southern black society that would have been untouched by demonstrations and federal voting legislation. Civil Rights activists in the Deep South, attempting to register voters, recognized the severe inadequacies of public education for black students and built parallel educational institutions designed to introduce black students to their rights as American citizens, develop local leadership and grassroots organizational structures. The methods the activists used to accomplish these goals had been pioneered in the mid-1950’s by Septima Clark and Myles Horton of the Highlander Folk School. Horton and Clark developed a successful curriculum structure for adult literacy and citizenship education that they implemented on Johns Island off the coast of South Carolina. -

Martin Luther King and Communism Page 20 the Complete Files of a Communist Front Organization Were Taken in a Raid in New Orleans

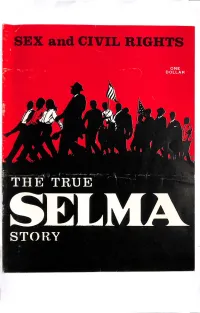

Several hundred demonstrators were forced to stand on Dexter Ave1me in front of the State Capitol at Montgomery. On the night of March 10, 1965, these demonstrators, who knew that once they left the area they would not be able to return, urinated en masse in the street on the signal of James Forman, SNCC ExecJJtiVe Director. "All right," Forman shoute<)l, "Everyone stand up and relieve yourself." Almost everyone did. Some arrests were made of men who went to obscene extremes in expos ing themselves to local police officers. The True SELMA Story Albert C. (Buck) Persons has lived in Birmingham, Alabama for 15 years. As a stringer for LIFE and managing editor of a metropolitan weekly newspaper he covered the Birmingham demonstrations in 1963. On a special assignment for Con gressman William L. Dickinson of Ala bama he investigated the Selma-Mont gomery demonstrations in March, 1965. In 1961 Persons was one of a handful of pilots hired to support the invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. His story on this two years later led to the admission by President Kennedy that four Ameri can flyers had died in combat over the beaches of Southern Cuba in an effort to drive Fidel Castro from the armed Soviet garrison that had been set up 90 miles off the coast of the United States. After interviewing scores of people who were eye-witnesses to the Selma-Montgomery march, Mr. Persons has written the articles published here. In summation he says, "The greatest obstacle in the Negro's search for "freedom" is the Negro himself and the leaders he has chosen to follow. -

HESCHEL-KING FESTIVAL Mishkan Shalom Synagogue January 4-5, 2013

THE HESCHEL-KING FESTIVAL Mishkan Shalom Synagogue January 4-5, 2013 “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “In a free society, when evil is done, some are guilty, but all are responsible.” Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., fourth from right, walking alongside Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, second from right, in the Selma civil rights march on March 21, 1965 Table of Contents Welcome...3 Featured Speakers....10 General Information....4 Featured Artists....12 Program Schedule Community Groups....14 Friday....5 The Heschel-King Festival Saturday Morning....5 Volunteers....17 Saturday Afternoon....6 Financial Supporters....18 Saturday Evening....8 Community Sponsors....20 Mishkan Shalom is a Reconstructionist congregation in which a diverse community of progressive Jews finds a home. Mishkan’s Statement of Principles commits the community to integrate Prayer, Study and Tikkun Olam — the Jewish value for repair of the world. The synagogue, its members and Senior Rabbi Linda Holtzman are the driving force in the creation of this Festival. For more info: www.mishkan.org or call (215) 508-0226. 2 Welcome to the Heschel-King Festival Thank you for joining us for the inaugural Heschel-King Festival, a weekend of singing together, learning from each other, finding renewal and common ground, and encouraging one another’s action in the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. Dr. King and Rabbi Heschel worked together in the battle for civil rights, social justice and peace. Heschel marched alongside King in Selma, Alabama, demanding voting rights for African Americans. -

Learning from History the Nashville Sit-In Campaign with Joanne Sheehan

Building a Culture of Peace Forum Learning From History The Nashville Sit-In Campaign with Joanne Sheehan Thursday, January 12, 2017 photo: James Garvin Ellis 7 to 9 pm (please arrive by 6:45 pm) Unitarian Universalist Church Free and 274 Pleasant Street, Concord NH 03301 Open to the Public Starting in September, 1959, the Rev. James Lawson began a series of workshops for African American college students and a few allies in Nashville to explore how Gandhian nonviolence could be applied to the struggle against racial segregation. Six months later, when other students in Greensboro, NC began a lunch counter sit-in, the Nashville group was ready. The sit- As the long-time New in movement launched the England Coordinator for Student Nonviolent Coordinating the War Resisters League, and as former Chair of War James Lawson Committee, which then played Photo: Joon Powell Resisters International, crucial roles in campaigns such Joanne Sheehan has decades as the Freedom Rides and Mississippi Freedom Summer. of experience in nonviolence training and education. Among those who attended Lawson nonviolence trainings She is co-author of WRI’s were students who would become significant leaders in the “Handbook for Nonviolent Civil Rights Movement, including Marion Barry, James Bevel, Campaigns.” Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash, and C. T. Vivian. For more information please Fifty-six years later, Joanne Sheehan uses the Nashville contact LR Berger, 603 496 1056 Campaign to help people learn how to develop and participate in strategic nonviolent campaigns which are more The Building a Culture of Peace Forum is sponsored by Pace e than protests, and which call for different roles and diverse Bene/Campaign Nonviolence, contributions. -

MESSENGER on the COVER in the Spirit of Sankofa

WINTER 2018 MESSENGER ON THE COVER In the Spirit of Sankofa A Publication of the The cover features the adinkra Sankofa heart symbol. Underneath is, an image of the autographed sentiment, “In the Spirit of Sankofa,” by Dr. Marlene O’Bryant-Seabrook. AVERY RESEARCH CENTER FOR AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE The autograph is from Georgette Mayo’s personal copy College of Charleston of A Communion of the Spirits: African-American Quilters, 125 Bull Street • Charleston, SC 29424 Preservers, and Their Stories by Roland Freeman (Rutledge Hill Ph: 843.953.7609 • Fax: 843.953.7607 Press 1996). Dr. O’Bryant-Seabrook is a featured quilt artist in Archives: 843.953.7608 the book. In the background is Dr. O’Bryant-Seabrook’s quilt, avery.cofc.edu Gone Clubbing: Crazy About Jazz (2008). Adinkra are visual symbols that AVERY INSTITUTE OF AFRO-AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE represent proverbs relating to history PO Box 21492 • Charleston, SC 29413 and customs of the Asante people of Ph: 843.953.7609 • Fax: 843.953.7607 West Africa. Sankofa means “go back www.averyinstitute.us to the past in order to build for the future.” We should learn from the past STAFF and move forward into the future with Patricia Williams Lessane, Executive Director that knowledge. A stylized heart, as Barrye Brown, Reference and Outreach Archivist featured on the cover, or a bird with Daron L. Calhoun II, RSJI Coordinator its head turned back while walking Curtis J. Franks, Curator; Coordinator of Public forward, are the two symbols used Programs and Facilities Manager to represent Sankofa.