Part Two: the First Amendment and the Right to Engage in the Mass Protest of State-Enforced Social Inequality Based on Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H

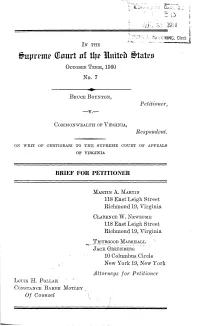

IN THE 71uprrmtr (21nrl of 11ir littitch tatras OCTOBER TERM, 1960 No. 7 BRUCE BOYNTON, Petitioner, -v.--- COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA BRIEF FOR PETITIONER MARTIN A. MARTIN 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia CLARENCE W. NEWSOME 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H. POLLAK CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY Of Counsel r a n TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opinions Below -------....-....-------- ------------------- 1 Jurisdiction ------------------------ ------------- 1 Questions Presented ------------------- ------------ 2 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved -.. 2 Statement --- --- .----------------------- ------------- 3 Summary of Argument ------..---------------------- 5 Argument -----------..--.....--- ----------- 6 Introductory ------------- -------------------- 6 The statute involved -- ---------------------- 6 Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8 I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab- lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti- tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu- larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal ------..------------- 14 II. Petitioner's criminal conviction which served only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restaurant conflicts with principles established by decisions of this Court, and there- by violates the Fourteenth Amendment --------- 22 Conclusion --- .--.--...---- 2626---... ii TABLE OF CASES PAGE Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ------------------- 11 Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 ----------- 15 Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 21 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 --------------------- 21 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. -

Movement 1954-1968

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT 1954-1968 Tuesday, November 27, 12 NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN AFFAIRS Curated by Ben Hazard Tuesday, November 27, 12 Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, The initial phase of the black protest activity in the post-Brown period began on December 1, 1955. Rosa Parks of Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat to a white bus rider, thereby defying a southern custom that required blacks to give seats toward the front of buses to whites. When she was jailed, a black community boycott of the city's buses began. The boycott lasted more than a year, demonstrating the unity and determination of black residents and inspiring blacks elsewhere. Martin Luther King, Jr., who emerged as the boycott movement's most effective leader, possessed unique conciliatory and oratorical skills. He understood the larger significance of the boycott and quickly realized that the nonviolent tactics used by the Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi could be used by southern blacks. "I had come to see early that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to the Negro in his struggle for freedom," he explained. Although Parks and King were members of the NAACP, the Montgomery movement led to the creation in 1957 of a new regional organization, the clergy-led Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) with King as its president. King remained the major spokesperson for black aspirations, but, as in Montgomery, little-known individuals initiated most subsequent black movements. On February 1, 1960, four freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College began a wave of student sit-ins designed to end segregation at southern lunch counters. -

Nominees and Bios

Nominees for the Virginia Emancipation Memorial Pre‐Emancipation Period 1. Emanuel Driggus, fl. 1645–1685 Northampton Co. Enslaved man who secured his freedom and that of his family members Derived from DVB entry: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Driggus_Emanuel Emanuel Driggus (fl. 1645–1685), an enslaved man who secured freedom for himself and several members of his family exemplified the possibilities and the limitations that free blacks encountered in seventeenth‐century Virginia. His name appears in the records of Northampton County between 1645 and 1685. He might have been the Emanuel mentioned in 1640 as a runaway. The date and place of his birth are not known, nor are the date and circumstances of his arrival in Virginia. His name, possibly a corruption of a Portuguese surname occasionally spelled Rodriggus or Roddriggues, suggests that he was either from Africa (perhaps Angola) or from one of the Caribbean islands served by Portuguese slave traders. His first name was also sometimes spelled Manuell. Driggus's Iberian name and the aptitude that he displayed maneuvering within the Virginia legal system suggest that he grew up in the ebb and flow of people, goods, and cultures around the Atlantic littoral and that he learned to navigate to his own advantage. 2. James Lafayette, ca. 1748–1830 New Kent County Revolutionary War spy emancipated by the House of Delegates Derived from DVB/ EV entry: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Lafayette_James_ca_1748‐1830 James Lafayette was a spy during the American Revolution (1775–1783). Born a slave about 1748, he was a body servant for his owner, William Armistead, of New Kent County, in the spring of 1781. -

Biography Bottle Project Due Date: February 3, 2015 Students Will

Biography Bottle Project Due Date: February 3, 2015 Students will learn as they celebrate Black History Month in February, by (1) researching facts {biographies/auto‐biographies/non‐fiction text} to write a 3 paragraph essay, in school, and (2) creating a Biography Bottles Statue/Image, at home, that will be displayed in our school library, during the month of February. It is important that all the deadlines listed below are met so that students do not fall behind and miss the due dates. The subject for the bio‐bottle project will be a famous African American that is selected, from a given list, by students and approved by the teacher on January 15th. The reading/research for this project will be done at home and at school. The reading/research should be completed by Wednesday, January 21st. Please have parents sign and return the slips listed below to teachers by Wednesday, January 21st. The completed Biography Bottle Statue/Image is due on Tuesday, February 3rd . Attached to this document is the grading rubric that I will use to for the bio bottle project. Materials needed for the bottle: 1 plastic bottle . For example: Small water or soda bottle 2 liter soda bottle Ketchup bottle Dish soap bottle o Please note the a minimum size should be at least 16 ounces, and the maximum size should be a 2 liter bottle Sand, dirt, or gravel to put in the bottom of your bottle to anchor it Things to decorate your bottle to look like the person you have researched . For example: Paint, yarn, glue, sequins, felt, beads, feathers, colored paper, pipe cleaners, Styrofoam balls, fabric, buttons, clay, googly eyes, etc. -

100 Facts About Rosa Parks on Her 100Th Birthday

100 Facts About Rosa Parks On Her 100th Birthday By Frank Hagler SHARE Feb. 4, 2013 On February 4 we will celebrate the centennial birthday of Rosa Parks. In honor of her birthday here is a list of 100 facts about her life. 1. Rosa Parks was born on Feb 4, 1913 in Tuskegee, Alabama. ADVERTISEMENT Do This To Fix Car Scratches This car gadget magically removes scratches and scuffs from your car quickly and easily. trynanosparkle.com 2. She was of African, Cherokee-Creek, and Scots-Irish ancestry. FEATURED VIDEOS Powered by Sen Gillibrand reveals why she's so tough on Al Franken | Mic 2020 NOW PLAYING 10 Sec 3. Her mother, Leona, was a teacher. 4. Her father, James McCauley, was a carpenter. 5. She was a member of the African Methodist Episcopal church. 6. She attended the Industrial School for Girls in Montgomery. 7. She attended the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes for secondary education. 8. She completed high school in 1933 at the age of 20. 9. She married Raymond Parker, a barber in 1932. 10. Her husband Raymond joined the NAACP in 1932 and helped to raise funds for the Scottsboro boys. 11. She had no children. 12. She had one brother, Sylvester. 13. It took her three tries to register to vote in Jim Crow Alabama. 14. She began work as a secretary in the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP in 1943. 15. In 1944 she briefly worked at Maxwell Air Force Base, her first experience with integrated services. 16. One of her jobs within the NAACP was as an investigator and activist against sexual assaults on black women. -

Montgomery Bus Boycott and Freedom Rides 1961

MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT AND FREEDOM RIDES 1961 By: Angelica Narvaez Before the Montgomery Bus Boycott vCharles Hamilton Houston, an African-American lawyer, challenged lynching, segregated public schools, and segregated transportation vIn 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality organized “freedom rides” on interstate buses, but gained it little attention vIn 1953, a bus boycott in Baton Rouge partially integrated city buses vWomen’s Political Council (WPC) v An organization comprised of African-American women led by Jo Ann Robinson v Failed to change bus companies' segregation policies when meeting with city officials Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) vVirginia's law allowed bus companies to establish segregated seating in their buses vDuring 1944, Irene Morgan was ordered to sit at the back of a Greyhound Bus v Refused and was arrested v Refused to pay the fine vNAACP lawyers William Hastie and Thurgood Marshall contested the constitutionality of segregated transportation v Claimed that Commerce Clause of Article 1 made it illegal v Relatively new tactic to argue segregation with the commerce clause instead of the 14th Amendment v Did not claim the usual “states rights” argument Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) v Supreme Court struck down Virginia's law v Deemed segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional v “Found that Virginia's law clearly interfered with interstate commerce by making it necessary for carriers to establish different rules depending on which state line their vehicles crossed” v Made little -

The Freedom Rides of 1961

The Freedom Rides of 1961 “If history were a neighborhood, slavery would be around the corner and the Freedom Rides would be on your doorstep.” ~ Mike Wiley, writer & director of “The Parchman Hour” Overview Throughout 1961, more than 400 engaged Americans rode south together on the “Freedom Rides.” Young and old, male and female, interracial, and from all over the nation, these peaceful activists risked their lives to challenge segregation laws that were being illegally enforced in public transportation throughout the South. In this lesson, students will learn about this critical period of history, studying the 1961 events within the context of the entire Civil Rights Movement. Through a PowerPoint presentation, deep discussion, examination of primary sources, and watching PBS’s documentary, “The Freedom Riders,” students will gain an understanding of the role of citizens in shaping our nation’s democracy. In culmination, students will work on teams to design a Youth Summit that teaches people their age about the Freedom Rides, as well as inspires them to be active, engaged community members today. Grade High School Essential Questions • Who were the key players in the Freedom Rides and how would you describe their actions? • Why do you think the Freedom Rides attracted so many young college students to participate? • What were volunteers risking by participating in the Freedom Rides? • Why did the Freedom Rides employ nonviolent direct action? • What role did the media play in the Freedom Rides? How does media shape our understanding -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Amelia Boynton Robinson

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Amelia Boynton Robinson Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Robinson, Amelia Boynton, 1911- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Amelia Boynton Robinson, Dates: September 4, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 7 Betacame SP videocasettes (3:24:55). Description: Abstract: Civil rights leader Amelia Boynton Robinson (1911 - 2015 ) was one of the civil rights leaders that led the famous first march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which became known as Bloody Sunday. She was also the first African American woman ever to seek a seat in Congress from Alabama. Robinson was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 4, 2007, in Tuskegee, Alabama. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_244 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Civil rights pioneer Amelia Boynton Robinson was born on August 18, 1911, in Savannah, Georgia. As a young lady, Robinson became very active in women’s suffrage. In 1934, at the age of twenty-three, Robinson became one of the few registered African American voters. In an era where literacy tests were used to discriminate against African Americans seeking to vote, Robinson used her status as a registered voter to assist other African American applicants to become registered voters. In 1930, while working as a home economics teacher in the rural south, Robinson became re-acquainted with Sam William Boynton, an extension agent for the county whom she had met while studying at Tuskegee Institute. -

The Evelyn T. Butts Story Kenneth Cooper Alexa

Developing and Sustaining Political Citizenship for Poor and Marginalized People: The Evelyn T. Butts Story Kenneth Cooper Alexander ORCID Scholar ID# 0000-0001-5601-9497 A Dissertation Submitted to the PhD in Leadership and Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Leadership and Change, Graduate School of Leadership and Change, Antioch University. Dissertation Committee • Dr. Philomena Essed, Committee Chair • Dr. Elizabeth L. Holloway, Committee Member • Dr. Tommy L. Bogger, Committee Member Copyright 2019 Kenneth Cooper Alexander All rights reserved Acknowledgements When I embarked on my doctoral work at Antioch University’s Graduate School of Leadership and Change in 2015, I knew I would eventually share the fruits of my studies with my hometown of Norfolk, Virginia, which has given so much to me. I did not know at the time, though, how much the history of Norfolk would help me choose my dissertation topic, sharpen my insights about what my forebears endured, and strengthen my resolve to pass these lessons forward to future generations. Delving into the life and activism of voting-rights champion Evelyn T. Butts was challenging, stimulating, and rewarding; yet my journey was never a lonely one. Throughout my quest, I was blessed with the support, patience, and enduring love of my wife, Donna, and our two sons, Kenneth II and David, young men who will soon begin their own pursuits in higher education. Their embrace of my studies constantly reminded me of how important family and community have been throughout my life. -

Freedom Riders Democracy in Action a Study Guide to Accompany the Film Freedom Riders Copyright © 2011 by WGBH Educational Foundation

DEMOCRACY IN ACTION A STUDY GUIDE TO ACCOMPANY THE FILM FREEDOM RIDERS DEMOCRACY IN ACTION A STUDY GUIDE TO ACCOMPANY THE FILM FREEDOM RIDERS Copyright © 2011 by WGBH Educational Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover art credits: Courtesy of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Back cover art credits: Bettmann/CORBIS. To download a PDF of this guide free of charge, please visit www.facinghistory.org/freedomriders or www.pbs.org/freedomriders. ISBN-13: 978-0-9819543-9-4 ISBN-10: 0-9819543-9-1 Facing History and Ourselves Headquarters 16 Hurd Road Brookline, MA 02445-6919 ABOUT FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES Facing History and Ourselves is a nonprofit and the steps leading to the Holocaust—the educational organization whose mission is to most documented case of twentieth-century engage students of diverse backgrounds in an indifference, de-humanization, hatred, racism, examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism antisemitism, and mass murder. It goes on to in order to promote a more humane and explore difficult questions of judgment, memory, informed citizenry. As the name Facing History and legacy, and the necessity for responsible and Ourselves implies, the organization helps participation to prevent injustice. Facing History teachers and their students make the essential and Ourselves then returns to the theme of civic connections between history and the moral participation to examine stories of individuals, choices they confront in their own lives, and offers groups, and nations who have worked to build a framework and a vocabulary for analyzing the just and inclusive communities and whose stories meaning and responsibility of citizenship and the illuminate the courage, compassion, and political tools to recognize bigotry and indifference in their will that are needed to protect democracy today own worlds. -

“Two Voices:” an Oral History of Women Communicators from Mississippi Freedom Summer 1964 and a New Black Feminist Concept ______

THE TALE OF “TWO VOICES:” AN ORAL HISTORY OF WOMEN COMMUNICATORS FROM MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM SUMMER 1964 AND A NEW BLACK FEMINIST CONCEPT ____________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________________________ by BRENDA JOYCE EDGERTON-WEBSTER Dr. Earnest L. Perry Jr., Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled: THE TALE OF “TWO VOICES:” AN ORAL HISTORY OF WOMEN COMMUNICATORS FROM MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM SUMMER 1964 AND A NEW BLACK FEMINIST CONCEPT presented by Brenda Joyce Edgerton-Webster, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Earnest L. Perry, Jr. Dr. C. Zoe Smith Dr. Carol Anderson Dr. Ibitola Pearce Dr. Bonnie Brennen Without you, dear Lord, I never would have had the strength, inclination, skill, or fortune to pursue this lofty task; I thank you for your steadfast and graceful covering in completing this dissertation. Of greatest importance, my entire family has my eternal gratitude; especially my children Lauren, Brandon, and Alexander – for whom I do this work. Special acknowledgements to Lauren who assisted with the audio and video recording of the oral interviews and often proved herself key to keeping our home life sound; to my fiancé Ernest Evans, Jr. who also assisted with recording interviews and has supported me in every way possible from beginning to end; to my late uncle, Reverend Calvin E. -

Civil Rights Resproj

TheAFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE in North Carolina The Civil Rights Movement North Carolina Freedom Monument Project Research Project Lesson Plan for Teachers: Procedures ■ Students will read the introduction and time line OBJECTIVE: To become familiar with of the Civil Rights Movement independently, as a significant events in the Civil Rights Movement small group or as a whole class. and their effects on North Carolina: ■ Students will complete the research project independently, as a small group or as a whole class. 1. Students will develop a basic understanding of, and ■ Discussion and extensions follow as directed by be able to define specific terms; the teacher. 2. Students will be able to make correlations between the struggle for civil rights nationally and in North Evaluation Carolina; ■ Student participation in reading and discussion of 3. Students will be able to analyze the causes and the time line. predict solutions for problems directly related to dis- ■ Student performance on the research project. criminatory practices. Social Studies Objectives: 3.04, 4.01, 4.03, 4.04, 4.05, 5.03, 6.04, 7.02, 8.01, 8.03, 9.01, 9.02, 9.03 Social Studies Skills: 1, 2, 3 Language Arts Objectives: 1.03, 1.04, 2.01, 5.01, 6.01, 6.02 Resources / Materials / Preparations ■ Time line ■ Media Center and/or Internet access for student research. ■ This research project will take two or three class periods for the introduction and discussion of the time line and to work on the definitions. The research project can be assigned over a two- or three-week period.