The 'Atomic' Despatch: Field Marshal Auchinleck, the Fall of the Tobruk Garrison and Post-War Anglo-South African Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 14 AUGUST, 1946 4097 Shortly Afterwards Our Troops Took Possession Eamichliye to a Point Where the Road Mosul- of the Town

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 14 AUGUST, 1946 4097 shortly afterwards our troops took possession Eamichliye to a point where the road Mosul- of the town. The railway and all railway in- Deir-ez-Zor crosses the Iraq-Syria frontier. .stallations up to the Turkish frontier had -been (iii) Lt. General Quinan was to submit captured intact as well as several bridges which his plans for holding the Northern Frontier had .been prepared for demolition. of Iraq against hostile advance through On 8th July, a column was sent to capture Anatolia or Iran. The construction of per- Hassetche, the seat of the local Government, manent defences in this area was to be con- in the Bee du Canard. Here the French de- fined to denying, where possible, the main cided not to fight and the town and fort were • lines of approach by armoured fighting occupied without opposition. vehicles into Iraq from Turkey or Iran with On gth July Ras el Ain was found to be the object of slowing up an advance and clear of French troops. Lack of motor trans- forcing it into unsuitable country. Plans in port made furtiher advance impossible. 5th detail were also to be prepared for an ad- Battalion I3th Frontier Force Rifles therefore vance into Turkish or Iranian territory in remained in occupation of the Bee du Canard order to seize defiles suitable for delaying covering the railway and the remainder of the action and to carry out extensive demoli- column returned to Mosul on I4th July. tions. 26. On return, of the Headquarters of I7th (iv) A suitable force was to be held in Indian Infantry Brigade to Mosul, the Head- readiness to enable the occupation of quarters of the aoth Indian Infantry Brigade Abadan and Naft-i-Shah to be carried out at moved to Baghdad, being better placed there short notice. -

Rite Works O Claud E

Rite W orks Volume VI Issue VII 1370 Grant Street July 2013 Denver, CO 80203 (303) 861-4261 DENVER CONSISTORY NEWS STAFF Rite Works DENVER CONSISTORY OFFICE o Claud E. Dutro, 33° Bulletin Advisory (303) 861-4261 Newsletter FAX (303) 861-4269 o Audrey Ford Technical Advisor & Correspondent Publications Committee (303) 861-4261 FAX (303) 861-4269 D. J. Cox, 33°, Chairman Bill Hickey, 32° KCCH John A. Moreno, 33° Staff Photographer Richard Silver, 32° (303) 238-3635 Jack D. White, 32° KCCH D. J. Cox, 33° Editor This publication is produced monthly by (970) 980-4340 and for the benefit of members, staff and Ashley S. Buss, 32° KCCH interested parties associated with the Webmaster Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, Southern Jurisdiction of the United States of America and, more particularly, the Denver Consistory in In this Issue: the Valley of Denver, Orient of Colorado. The views expressed in this Remembrance – Memorial Roll 3 publication do not necessarily reflect Calendar 4 those of the Denver Consistory or its Feature Article: Did You Know That? 5 officers. Enthusiasm, Value and Commitment 6 Deadline for articles is two (2) days after the monthly stated The Mason’s Home 6 meeting. Submitted articles should be 250 to 1,000 words. Where appropriate, relevant high-resolution images with I Am Freemasonry 7 proper credits may be included with your submission. Images will normally be restricted to a maximum 3.5” by Scottish Rite Caps 8-9 3.5” size, but may be larger in special circumstances. Articles may be submitted in hard copy to the office or Ye Happy Few 9 electronic form via email. -

The Attack Will Go on the 317Th Infantry Regiment in World War Ii

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2003 The tta ack will go on the 317th Infantry Regiment in World War II Dean James Dominique Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Dominique, Dean James, "The tta ack will go on the 317th Infantry Regiment in World War II" (2003). LSU Master's Theses. 3946. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3946 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ATTACK WILL GO ON THE 317TH INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts In The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Dean James Dominique B.S., Regis University, 1997 August 2003 i ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MAPS........................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT................................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 -

From the Desert Sands to the Burmese Jungle: the Indian Army and the Lessons of North Africa, September 1939–November 1942

CHAPTER SEVEN FROM THE DESERT SANDS TO THE BURMESE JUNGLE: THE INDIAN ARMY AND THE LESSONS OF NORTH AFRICA, SEPTEMBER 1939–NOVEMBER 1942 Tim Moreman Introduction The Indian Army contingent that fought in North Africa against German and Italian troops between 1939–42 formed a comparatively small part of the polyglot British Commonwealth armies, drawn from the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and smaller Allied countries. The degree to which different Indian Army formations took part in the Western Desert varied enormously. The 4th Indian Division was arguably the most experienced of all British formations in the theatre, seeing nearly two and half years of combat, with only a few brief intermissions to rest, retrain and reorganize, by November 1942. The 5th Indian Division also made a significant albeit smaller contribution to the desert war, after being blooded in Eritrea, before eventually returning to India in 1943. A relatively smaller part was played by 10th Indian Division from May–June 1942, when it was caught up in the tail end of the Gazala battles, savaged while escap- ing from Mersa Matruh and then participated in the defence of El Alamein. A single brigade of 8th Indian Division—the inexperienced 18th Indian Infantry Brigade—was rushed forward in July 1942, more- over, to El Alamein and was destroyed by German panzers at Deir El Shein on 1st July 1942.1 The unfortunate independent 3rd Indian Motor Brigade was also deployed in the Western Desert where on two separate occasions it was overwhelmed by Axis troops. A large num- ber of British officers from the Indian service also held senior com- mand and staff appointments in Middle East Command, particularly 1 For an early account of the Indian Army in North Africa see The Tiger Strikes and the Tiger Kills: The Story of the Indian Divisions in the North African Campaigns (London: 1944). -

Military History Anniversaries 1 Thru 15 July

Military History Anniversaries 1 thru 15 July Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests JUL 00 1940 – U.S. Army: 1st Airborne Unit » In 1930, the U.S. Army experimented with the concept of parachuting three-man heavy-machine-gun teams. Nothing came of these early experiments. The first U.S. airborne unit began as a test platoon formed from part of the 29th Infantry Regiment, in July 1940. The platoon leader was 1st Lieutenant William T. Ryder, who made the first jump on August 16, 1940 at Lawson Field, Fort Benning, Georgia from a B-18 Bomber. He was immediately followed by Private William N. King, the first enlisted soldier to make a parachute jump. Although airborne units were not popular with the top U.S. Armed Forces commanders, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sponsored the concept, and Major General William C. Lee organized the first paratroop platoon. On a tour of Europe he had first observed the revolutionary new German airborne forces which he believed the U.S. Army should adopt. This led to the Provisional Parachute Group, and then the United States Army Airborne Command. General Lee was the first commander at the new parachute school at Fort Benning, in west-central Georgia. The U.S. Armed Forces regards Major General William C. Lee as the father of the Airborne. The first U.S. combat jump was near Oran, Algeria, in North Africa on November 8, 1942, conducted by elements of the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment. -

Life in the Army in British India (Related Reading)

Life in the Army in British India (Related reading) 1) “Stringer Lawrence: Father of the Indian Army” by Colonel J. Biddulph, London, 1901, first edition; hardcover; 1 map; 2 tables; 133pp. The life of the British Army officer who rose to become the first Commander-in-Chief of the HEIC’s army and became known as “the Father of the Indian Army”. 2) “From Sepoy to Subedar: Being the Life and Adventures of Subedar Sita Ram, a Native Officer of the Bengal Army ( as translated by Lt. Colonel Norgate, Lahore, 1873)” Edited by James Lunt (late 16th. Royal Lancers and 4th. Burma Rifles). A 1970 reprint; London; hardcover; The Hindi original was printed as the text-book which young British officers of the Indian Army had to translate into English as part of their language competency examination. An excellent and rare insight into service in the old pre-Mutiny Bengal Army of the Hon. East India Company by an Indian who rose through the ranks. 3) “Tales of the Mountain Gunners” edited by C.H.T. MacFetridge and J.P. Warren; Edinburgh, 1973; hardcover; 22 illustrations; 11 maps; 327 pp. An anthology of tales and short stories by those who served in one of the most unusual and colourful units in the history of the British Empire: the Mountain Artillery. Its reputation for action attracted a collection of adventurous, able and eccentric officers; usually with a combination of all three qualities. 4) “The Martial Races of India” by Lt. Gen. Sir George MacMunn, KCB; KCSI; DSO; London, 1932; hardcover; 19 illustrations; 2 maps; 368 pp. -

Airpower and Ground Armies : Essays on the Evolution of Anglo-American Air Doctrine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Airpower and ground armies : essays on the evolution of Anglo-American air doctrine. 1940- 1943/ editor, Daniel R Mortensen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Air power-Great Britain-History. 2. Air power-United States-History. 3. World War, 1939-1945- Aerial operations, British, 4. World War, 1939-1945-Aerial operations, American. 5. World War, 1939-1945-Campaigns-Africa, North. 6. Operation Torch. I. Mortensen, Daniel R. UG635.G7A89 1998 358.4’03-dc21 97-46744 CIP Digitize December 2002 from 1998 Printing NOTE: Pagination changed Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Table of Contents Page DISCLAIMER ..................................................................................................................... i FORWARD........................................................................................................................ iii ABOUT THE EDITOR .......................................................................................................v INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. vi GETTING TOGETHER ......................................................................................................1 -

ED 194 419 EDRS PRICE Jessup, John E., Jr.: Coakley, Robert W. A

r r DOCUMENT RESUME ED 194 419 SO 012 941 - AUTHOR Jessup, John E., Jr.: Coakley, Robert W. TITLE A Guide to the Study and use of Military History. INSTITUTION Army Center of Military History, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 497p.: Photographs on pages 331-336 were removed by ERIC due to poor reproducibility. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 ($6.50). EDRS PRICE MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *History: military Personnel: *Military Science: *Military Training: Study Guides ABSTRACT This study guide On military history is intended for use with the young officer just entering upon a military career. There are four major sections to the guide. Part one discusses the scope and value of military history, presents a perspective on military history; and examines essentials of a study program. The study of military history has both an educational and a utilitarian value. It allows soldiers to look upon war as a whole and relate its activities to the periods of peace from which it rises and to which it returns. Military history also helps in developing a professional frame of mind and, in the leadership arena, it shows the great importance of character and integrity. In talking about a study program, the guide says that reading biographies of leading soldiers or statesmen is a good way to begin the study of military history. The best way to keep a study program current is to consult some of the many scholarly historical periodicals such as the "American Historical Review" or the "Journal of Modern History." Part two, which comprises almost half the guide, contains a bibliographical essay on military history, including great military historians and philosophers, world military history, and U.S. -

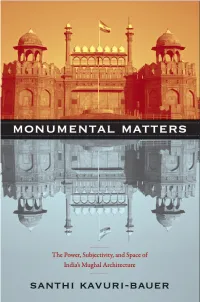

The Power, Subjectivity, and Space of India's Mughal Architecture

monumental matters monumental matters The Power, Subjectivity, and Space of India’s Mughal Architecture Santhi Kavuri-Bauer Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by April Leidig-Higgins Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. In memory of my father, Raghavayya V. Kavuri contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 Breathing New Life into Old Stones: The Poets and Artists of the Mughal Monument in the Eighteenth Century 19 2 From Cunningham to Curzon: Producing the Mughal Monument in the Era of High Imperialism 49 3 Between Fantasy and Phantasmagoria: The Mughal Monument and the Structure of Touristic Desire 76 4 Rebuilding Indian Muslim Space from the Ruins of the Mughal “Moral City” 95 5 Tryst with Destiny: Nehru’s and Gandhi’s Mughal Monuments 127 6 The Ethics of Monumentality in Postindependence India 145 Epilogue 170 Notes 179 Bibliography 197 Index 207 acknowledgments This book is the result of over ten years of research, writing, and discus- sion. Many people and institutions provided support along the way to the book’s final publication. I want to thank the UCLA International Institute and Getty Museum for their wonderful summer institute, “Constructing the Past in the Middle East,” in Istanbul, Turkey in 2004; the Getty Foundation for a postdoctoral fellowship during 2005–2006; and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts Grant Award for a subvention grant toward the costs of publishing this book. -

Mountbatten, Auchinleck and the End of British Indian Army: August-November 1947

Loughborough University Institutional Repository Mountbatten, Auchinleck and the end of British Indian Army: August-November 1947 This item was submitted to Loughborough University's Institutional Repository by the/an author. Citation: ANKIT, R., 2018. Mountbatten, Auchinleck and the end of British Indian Army: August-November 1947. Britain and the World, [forthcoming]. Additional Information: • This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article that will be published by Edinburgh University Press in Britain and the World. The Version of Record will be available online at: https://www.euppublishing.com/loi/brw. Metadata Record: https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/35103 Version: Accepted for publication Publisher: c Edinburgh University Press Rights: This work is made available according to the conditions of the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) licence. Full details of this licence are available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Please cite the published version. 1 Mountbatten, Auchinleck and the end of British Indian Army: August-November 1947 Abstract Juxtaposing the private papers of Louis Mountbatten and Claude Auchinleck, this article seeks to illuminate the crux at the centre of the reconstitution of the British Indian army into Indian and Pakistani armies, namely, their worsening relationship between April and November 1947, in view of what they saw as each other’s partisan position and its consequences, the closure of Auchinleck’s office and his departure from India. In doing so in considerable detail, it brings to fore yet another aspect of that fraught period of transition at the end of which the British Indian Empire was transformed into the dominions of India and Pakistan and showcases the peculiar predilections in which the British found themselves during the process of transfer of power. -

The Pakistan Army Officer Corps, Islam and Strategic Culture 1947-2007

The Pakistan Army Officer Corps, Islam and Strategic Culture 1947-2007 Mark Fraser Briskey A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW School of Humanities and Social Sciences 04 July 2014 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). I have either used no substantial portions of copyright material in my thesis or I have obtained permission to use copyright material; where permission has not been granted I have applied/ ·11 apply for a partial restriction of the digital copy of my thesis or dissertation.' Signed t... 11.1:/.1!??7 Date ...................... /-~ ....!VP.<(. ~~~-:V.: .. ......2 .'?. I L( AUTHENTICITY STATEMENT 'I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. No emendation of content has occurred and if there are any minor Y, riations in formatting, they are the result of the conversion to digital format.' · . /11 ,/.tf~1fA; Signed ...................................................../ ............... Date .