Imperial Influence on the Postcolonial Indian Army, 1945-1973

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 104 – July 2020

THE TIGER Homes for heroes by the sea . THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 104 – JULY 2020 CHAIRMAN’S COLUMN Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to The Tiger. Whilst the first stage of the easing of the “lockdown” still prevent us from re-uniting at Branch Meetings, there is still a certain amount of good news emanating from the “War Front”. In Ypres, from 1st July, members of the public will be permitted to attend the Last Post Ceremony, although numbers will be limited to 152, with social distancing of 1.5 metres observed. 1st July will also see the re-opening of Talbot House in Poperinghe. Readers will be pleased to learn that the recent fund-raising appeal for the House, featured in this very column in the May edition of The Tiger reached its required target and my thanks go to those of you who donated to this worthy cause. Another piece of news has, as yet, received scant publicity but could prove to be the most important of all. In the aftermath of the recent “attack” on the Cenotaph, during which an attempt was made to set alight our national flag, I was delighted to read in the Press that: a Desecration of War Memorials Bill, carrying a ten year prison sentence, would be brought before the Commons as a matter of urgency. The subsequent discovery that ten years was the maximum sentence rather than the minimum tempered my joy somewhat, but the fact that War Memorials are now finally to be legally placed on a higher plane than other statuary is, at least in my opinion, a major step forward in their protection. -

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

A Look Into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan Over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori

A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir https://www.e-ir.info/2020/10/07/a-look-into-the-conflict-between-india-and-pakistan-over-kashmir/ PRANAV ASOORI, OCT 7 2020 The region of Kashmir is one of the most volatile areas in the world. The nations of India and Pakistan have fiercely contested each other over Kashmir, fighting three major wars and two minor wars. It has gained immense international attention given the fact that both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers and this conflict represents a threat to global security. Historical Context To understand this conflict, it is essential to look back into the history of the area. In August of 1947, India and Pakistan were on the cusp of independence from the British. The British, led by the then Governor-General Louis Mountbatten, divided the British India empire into the states of India and Pakistan. The British India Empire was made up of multiple princely states (states that were allegiant to the British but headed by a monarch) along with states directly headed by the British. At the time of the partition, princely states had the right to choose whether they were to cede to India or Pakistan. To quote Mountbatten, “Typically, geographical circumstance and collective interests, et cetera will be the components to be considered[1]. -

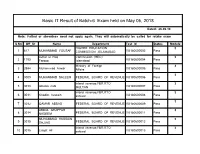

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

Grenadier News the Autumn Newsletter of the Grenadier Guards Association

www.grengds.com Grenadier News The Autumn Newsletter of the Grenadier Guards Association Edition 3, October 2016 Association Headquarters President: Colonel REH Aubrey-Fletcher General Secretary & Regimental Treasurer: Major AJ Green Association Senior Non-Commissioned Officer: Sgt R Broomes Regimental Headquarters The Lieutenant Colonel: Lieutenant General Sir George Norton, KCVO, CBE Regimental Adjutant: Major GVA Baker Regimental Archivist: Captain AGH Ogden Assistant Equerry: Captain FCB Moynan Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant: WO2 (RQMS) M Cox Regimental Affairs Non-Commissioned Officer: LSgt R Haughton Regimental Property Non-Commissioned Officer: LSgt M MacMillan Civilian Clerk: Mr Edward (Yomi) Fowowe Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk, LONDON, SW1E 6HQ REGIMENTAL HEADQUARTERS The Regimental Adjutant In January, the 1st Battalion mounted its last Queen’s Guard and on completion moved from London District to the 11th Infantry Brigade. The Battalion has a challenging two years ahead. In 2017 it will assume the role of lead Battlegroup of the NATO Very High Readiness Joint Task Force; this force is designed to deter further Russian aggression in Eastern Europe. 2016 is being spent training in preparation for this role. Some may recall that in 2015, the Battalion earned glowing reports for its performance on exercise in Kenya; in June this year, the Battalion deployed once more to Kenya and earned another first class report, this time whilst carrying out an even more demanding exercise. Currently, and until the end of the year there are various exercises in the UK, Germany and Eastern Europe. The Battlegroup will consist of Battalion Headquarters, a rifle company, Support Company and logistic support from the 1st Battalion, together with 1 www.thegrenadierguards.com www.grengds.com Dutch, Albanian and Latvian Companies. -

Bhu Puu 2014

BHU PUU 2014 The Editor Bhu Puu Journal Welfare Branch, Defence Wing, Embassy of India G.P.O. Post Box No. 292, Kathmandu, Nepal Journal of Indian Ex-Servicemen Tel: 00977–1–4412597; E–mail: [email protected] Welfare Organisation in Nepal Design and Print by: Creative Press Pvt. Ltd. STRENgTHENINg BONDS INDIAN ARMY DAY CELEBRATIONS 2014 : AN RENDEZVOUS WITH OUR VETERANS Indian Army Day was celebrated by and professionalism. He acknowledged Defence Wing, Embassy of India, Nepal Indian Army as a reputed Institution of in Kathmandu on ... Jan 2014. Gen world repute. The highlight of the evening Gaurav SJB Rana, COAS, Nepalese was the presence of our gallantry award Army and Hony General of Indian Army winners. The event was also attended was the Chief Guest of the event. The by prominent dignitaries including senior proceedings commenced with inaugural officials of NA and various ministries of address by His Excellency Mr Ranjit GoN, representatives from diplomatic Rae, the Ambassador of India in Nepal. missions in Nepal, media personnel, Thereafter COAS, NA read out his artist community and heads of important message in which he appreciated Indian corporate houses including the Indian Army's rich history of selfless sacrifice joint ventures. COAS NA ADDRESSING THE GATHERING THE AMBASSADOR WITH OUR WAR HEROES COAS WITH THE OFFICERS OF DEFENCE WING CONTENTS Messages - 3 Visit of The Prime Minister of India - 6 COAS Visit - 8 Visits - 10 Defence Wing in Nepal - 11 Welfare Branch - 12 Medical Facilities - 14 Educational Assistance - 18 ECHS -

T He Indian Army Is Well Equipped with Modern

Annual Report 2007-08 Ministry of Defence Government of India CONTENTS 1 The Security Environment 1 2 Organisation and Functions of The Ministry of Defence 7 3 Indian Army 15 4 Indian Navy 27 5 Indian Air Force 37 6 Coast Guard 45 7 Defence Production 51 8 Defence Research and Development 75 9 Inter-Service Organisations 101 10 Recruitment and Training 115 11 Resettlement and Welfare of Ex-Servicemen 139 12 Cooperation Between the Armed Forces and Civil Authorities 153 13 National Cadet Corps 159 14 Defence Cooperaton with Foreign Countries 171 15 Ceremonial and Other Activities 181 16 Activities of Vigilance Units 193 17. Empowerment and Welfare of Women 199 Appendices I Matters Dealt with by the Departments of the Ministry of Defence 205 II Ministers, Chiefs of Staff and Secretaries who were in position from April 1, 2007 onwards 209 III Summary of latest Comptroller & Auditor General (C&AG) Report on the working of Ministry of Defence 210 1 THE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT Troops deployed along the Line of Control 1 s the world continues to shrink and get more and more A interdependent due to globalisation and advent of modern day technologies, peace and development remain the central agenda for India.i 1.1 India’s security environment the deteriorating situation in Pakistan and continued to be infl uenced by developments the continued unrest in Afghanistan and in our immediate neighbourhood where Sri Lanka. Stability and peace in West Asia rising instability remains a matter of deep and the Gulf, which host several million concern. Global attention is shifting to the sub-continent for a variety of reasons, people of Indian origin and which is the ranging from fast track economic growth, primary source of India’s energy supplies, growing population and markets, the is of continuing importance to India. -

CANADA's SIBERIAN POLICY I918

CANADA'S SIBERIAN POLICY i918 - 1919 ROBERT NEIL MURBY B.A,, University of British Columbia, 1968 A1 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the DEPARTMENT OF SLAVONIC STUDIES We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard. THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1969 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and Study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thes,is for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Robert N. Murby Department of Slavonic Studies The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Da 1e April 17th. 1969 - ii - ABSTRACT The aim of this essay was to add to the extremely limited fund of knowledge regarding Canada's relations with Siberia during the critical period of the Intervention, The result hopefully is a contribution both to Russian/Soviet and Canadian history. The scope of the subject includes both Canada's military participation in the inter-allied intervention and simultaneously the attempt on the part of Canada to economically penetrate Siberia, The principal research was carried out at the Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa during September and October, 1968. The vast majority of the documents utilized in this essay have never previously been published either in whole or in part. -

MAJOR GENERAL RAYMOND F. REES the Adjutant General, Oregon National Guard

MAJOR GENERAL RAYMOND F. REES The Adjutant General, Oregon National Guard Major General Raymond F. Rees assumed duties as The Adjutant General for Oregon on July 1, 2005. He is responsible for providing the State of Oregon and the United States with a ready force of citizen soldiers and airmen, equipped and trained to respond to any contingency, natural or manmade. He directs, manages, and supervises the administration, discipline, organization, training and mobilization of the Oregon National Guard, the Oregon State Defense Force, the Joint Force Headquarters and the Office of Oregon Emergency Management. He is also assigned as the Governor’s Homeland Security Advisor. He develops and coordinates all policies, plans and programs of the Oregon National Guard in concert with the Governor and legislature of the State. He began his military career in the United States Army as a West Point cadet in July 1962. Prior to his current assignment, Major General Rees had numerous active duty and Army National Guard assignments to include: service in the Republic of Vietnam as a cavalry troop commander; commander of the 116th Armored Calvary Regiment; nearly nine years as the Adjutant General of Oregon; Director of the Army National Guard, National Guard Bureau; over five years service as Vice Chief, National Guard Bureau; 14 months as Acting Chief, National Guard Bureau; Chief of Staff (dual-hatted), Headquarters North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). NORAD is a binational, Canada and United States command. EDUCATION: US Military Academy, West Point, New York, BS University of Oregon, JD (Law) Command and General Staff College (Honor Graduate) Command and General Staff College, Pre-Command Course Harvard University Executive Program in National and International Security Senior Reserve Component Officer Course, United States Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania 1 ASSIGNMENTS: 1. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

World Literature for the Wretched of the Earth: Anticolonial Aesthetics

W!"#$ L%&'"(&)"' *!" &+' W"'&,+'$ !* &+' E("&+ Anticolonial Aesthetics, Postcolonial Politics -. $(.%'# '#(/ Fordham University Press .'0 1!"2 3435 Copyright © 3435 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available online at https:// catalog.loc.gov. Printed in the United States of America 36 33 35 7 8 6 3 5 First edition C!"#$"#% Preface vi Introduction: Impossible Subjects & Lala Har Dayal’s Imagination &' B. R. Ambedkar’s Sciences (( M. K. Gandhi’s Lost Debates )* Bhagat Singh’s Jail Notebook '+ Epilogue: Stopping and Leaving &&, Acknowledgments &,& Notes &,- Bibliography &)' Index &.' P!"#$%" In &'(&, S. R. Ranganathan, an unknown literary scholar and statistician from India, published a curious manifesto: ! e Five Laws of Library Sci- ence. ) e manifesto, written shortly a* er Ranganathan’s return to India from London—where he learned to despise, among other things, the Dewey decimal system and British bureaucracy—argues for reorganiz- ing Indian libraries. -

Men-On-The-Spot and the Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920 Undergraduate

A Highly Disreputable Enterprise: Men-on-the-Spot and the Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920 Undergraduate Research Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation "with Honors Research Distinction in History" in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Conrad Allen The Ohio State University May 2016 Project Advisor: Professor Jennifer Siegel, Department of History The First World War ended on November 11, 1918. The guns that had battered away at each other in France and Belgium for four long years finally fell silent at eleven A.M. as the signed armistice went into effect. "There came a second of expectant silence, and then a curious rippling sound, which observers far behind the front likened to the noise of a light wind. It was the sound of men cheering from the Vosges to the sea," recorded South African soldier John Buchan, as victorious Allied troops went wild with celebration. "No sleep all night," wrote Harry Truman, then an artillery officer on the Western Front, "The infantry fired Very pistols, sent up all the flares they could lay their hands on, fired rifles, pistols, whatever else would make noise, all night long."1 They celebrated their victory, and the fact that they had survived the worst war of attrition the world had ever seen. "I've lived through the war!" cheered an airman in the mess hall of ace pilot Eddie Rickenbacker's American fighter squadron. "We won't be shot at any more!"2 But all was not quiet on every front.