The Power, Subjectivity, and Space of India's Mughal Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

215 the History and Practice of Naming Streets in Delhi

International Journal of Advanced Research and Development International Journal of Advanced Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4030, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.advancedjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 3; May 2017; Page No. 215-218 The history and practice of naming streets in Delhi Nidhi M.A (F), Delhi School of Economics, Delhi, India Introduction: History of Streets which naming streets took place have changed considerably. The word ‘Street’ was borrowed from Latin language. The Delhi, India’s capital is believed to be one of the oldest cities Roman strata or paved roads were taken up to drive the word of the world. From Indraprastha to New Delhi, it had been a street. The word street helps us to recognise the roman roads long journey. As popularly believed, Delhi has been the site which were straight as an arrow, connecting the strategic for seven historic cities- Lalkot, Siri, Tughlaqabad, Jahan positions in the region. Panah, Ferozabad, Purana Quila and Shahajahanabad. The early forms of street transport were horses or even Shahajahanabad remains a living city till present housing humans carrying goods over tracks. The first improved trails about half a million people. would have been at mountain passes and through swamps. As 2.5.1 Street names of Shahajahanabad: Mughal Capital trade increased, the tracks were often flattened or widened to The seventh city of Delhi, Shahajahanabad was built in 1638 accommodate human and animal traffic, Some of these soil on the banks of river Yamuna. The two major streets of tracks were developed into broad networks, allowing Shahajahanabad were Chandni Chowk and Faiz Bazaar. -

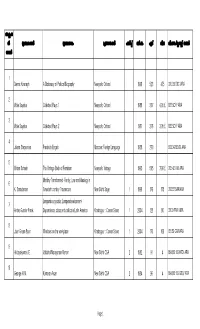

V. Aravindakshan 2.Xlsx

അക്സഷ ന് ഗര്ന്ഥകാരന് ഗര്ന്ഥനാമം പര്സാധകന് പതിപ്പ് വര്ഷംഏട്വിലവിഷയം/കല്ാസ്സ് നമ്പര് നമ്പര് 1 Dennis Kavnagh A Dictionary of Political Biography Newyork: Oxford 1998 523 475 320.092 DIC /ARA 2 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 1 Newyork: Oxford 1988 307 4.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 3 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 2 Newyork: Oxford 1987 276 3.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 4 Jelena Stepanova Frederick Engels Moscow: Foreign Language 1958 270 923.343 ENG/ ARA 5 Miriam Schneir The Vintage Book of Feminism Newyork: Vintage 1995 505 7.99 £ 305.42 VIN/ ARA 6 Matriliny Transformed -Family, Law and Ideology in K. Saradamoni Twenteth century Travancore New Delhi: Sage 1 1999 176 175 306.83 SAR/ARA 7 Lumpenbourgeoisle: Lumpendevelopment- Andre Gunder Frank Dependence, class and politics in Latin America Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 128 80 320.9 FRA/ ARA 8 Joan Green Baun Windows on the workplace Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 170 100 651.59 GRA/ARA 9 Hridayakumari. E. Vallathol Narayanan Menon New Delhi: CSA 2 1982 91 4 894.812 109 HRD/ ARA 10 George. K.M. Kumaran Asan New Delhi: CSA 2 1984 96 4 894.812 109 GEO/ ARA Page 1 11 Tharakan. K.M. M.P. Paul New Delhi: CSA 1 1985 96 4 894.812 109 THA/ ARA 12 335.43 AJI/ARA Ajit Roy Euro-Communism' An Analytical story Calcutta: Pearl 88 10 13 801.951 MAC/ARA Archi Bald Macleish Poetry and Experience Australia: Penguin Books 1960 187 Alien Homage' -Edward Thompson and 14 891.4414 THO/ARA E.P. Thompson Rabindranath Tagore New Delhi : Oxford 2 1998 175 275 15 894.812309 VIS/ARA R.Viswanathan Pottekkatt New Delhi: CSA 1 1998 60 5 16 891.73 CHE/ARA A.P. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

Kevin Milburn, Delhi Durbar Dress. in Derbyshire.Pdf

Dr Kevin Milburn Delhi Durbar Dress. In Derbyshire. And so, with a final intense, some may say frantic, period of work, the prototype stage of our project has come to an end. All the archival work in London – such as at the British Film Institute, the National Portrait Gallery and nosing around inside Carlton House Terrace – is completed; the correspondence with American institutions, such as the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress, is over; the star-gazing at ‘celebrity’ authors and historians – step forward Owen Jones, Tristram Hunt and Kate Williams, all similarly beavering away in The British Library – is no more. All of which makes me a little sad. Following soon after that stage of the project, came the onset of the most recent editing phase, which has largely revolved around copy editing and proofing written texts for the app as well as audio/film scripts associated with it. However, in between hunter-gathering information and then giving it a bit of a polish (hopefully) came a rather jolly and extremely productive away-day, one that took me and Nicola away from this project’s more usual Exeter St. David’s-London Paddington axis, to the quiet foothills of the south-eastern corner of the Pennines, and, more specifically still, to Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire. Kedleston Hall, National Trust. Photograph: Kevin Milburn Dr Kevin Milburn Built in the mid-18th century by renowned architect Robert Adam to be the country seat of the Curzon family, Kedleston Hall is now a popular National Trust property. And it was here, that a group of enthusiastic, good hearted, shivering and, initially, blurry eyed, people, gathered to film and photograph − courtesy of 360 degree SpinMe technology − the most famous outfit associated with the subject of our app, Mary Curzon: the Peacock Dress. -

King for a Day Teacher's Guide

King for a Day Teacher’s Guide for Grades K - 3 With Student Activity Sheets by Rukhsana Khan www.rukhsanakhan.com About Rukhsana Khan Rukhsana has been writing seriously since 1989. Currently she has twelve books published, several of which have been nominated and/or won awards. She is an accomplished storyteller and has performed at numerous festivals. For more information on Rukhsana and her books please visit her website: www.rukhsanakhan.com Rukhsana was born in Lahore, Pakistan and immigrated to Canada, with her family, at the age of three. She began by writing for community magazines and went on to write songs and stories for the Adam's World children's videos. Rukhsana is a member of SCBWI, The Writers Union of Canada and Storytelling Toronto. She lives in Toronto with her husband and family. To see the video book talk/tutorials for King for a Day and other titles, check out Ru khsana‘s Youtube chann el Books by Rukhsana: https://www.youtube.com/user/MsRukhsanaKhan King for a Day Big Red Lollipop Wanting Mor A New Life Many Windows Silly Chicken Ruler of the Courtyard The Roses in My Carpets Muslim Child King of the Skies Bedtime Ba-a-a-lk Dahling if You Luv Me Would You Please Please Smile King for a Day Teacher’s Guide by Rukhsana Khan Page 2 The following curriculum applications are fulfilled by the discussion topics and activities outlined in this teacher’s guide: Legend writing applications character applications visual art math applications applications drama applications Social Studies For insights into the creation of this book, read the interview between the author Rukhsana Khan and the illustrator Christiane Kromer in Appendix 1 Discussion Topics before reading the book (Reading Standards, Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strand 7) (Speaking & Listening Standards, Comprehension & Collaboration, Strands 1 and 2) Grades K - 3: Examine the cover of King for a Day. -

Administration of India Under the Mughul Emperors

Course: B.A History Honors Semester: B.A. 4th semester Code: 410 Topic:Administration of India under the Mughul Emperors Prepared by: Dr Sangeeta Saxena, Assistant Professor Department: History, Patna Women's College, Patna E mail: [email protected] Administration of India under the Mughul Emperors Content: 1 Central Administration of India under the Mughul emperors 2. Provincial Administration and local administration 3.. Military administration. 4. Financial Administration 5. Law and Justice. The Central Administration: Mughul emperors brought about certain fundamental changes in the administrative structure in India. Babur, the founder of the Mughul empire, assumed the title of Padshah (emperor) which was continued by his successors. It meant that the Mughul emperors did not accept the Khalifa even as their nominal overlord. Thus, the Mughul emperors were completely free from even the nominal authority of any foreign power or individual. Akbar enhanced further the power and prestige of the emperor. He declared himself the arbiter in case of difference of opinions regarding Islamic laws. The Mughul rule was also not theocratic. Except Aurangzeb no other Mughul emperor attempted to carry his administration on principles of Islam. The Mughul rule was not a police state as well. The emperors accepted two primary duties for themselves—Jahanbani (protection of the state) and Jahangiri (extension of the empire). Besides, they tried to create those conditions which were conducive to economic and cultural progress of their subjects. Another novelty of the Mughuls was that they began the policy of religious toleration. Babur and Humayun were no bigots while Akbar pursued the policy of equal respect to all religions. -

THE HINDU EDITORIAL on a VARANASI COURT ORDERING an ASI SURVEY in GYANVAPI MOSQUE Relevant For: Null | Topic: Indian Architecture Incl

Source : www.thehindu.com Date : 2021-04-10 A DISTURBING ORDER: THE HINDU EDITORIAL ON A VARANASI COURT ORDERING AN ASI SURVEY IN GYANVAPI MOSQUE Relevant for: null | Topic: Indian Architecture incl. Art & Craft & Paintings The order of a civil court in Varanasi that the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) should conduct a survey to ascertain whether the Gyanvapi mosque was built over a demolished Hindu temple is an unconscionable intervention that will open the floodgates for another protracted religious dispute. The order, apparently in gross violation of the explicit legislative prohibition on any litigation over the status of places of worship, is likely to give a fillip to majoritarian and revanchist forces that earlier carried on the Ram Janmabhoomi movement over a site in Ayodhya. That dispute culminated in the country’s highest court handing over the site to the very forces that conspired to illegally demolish the Babri Masjid. The plaintiffs, who have filed a suit as representatives of Hindu faith to reclaim the land on which the mosque stands, have now succeeded in getting the court to commission an ASI survey to look for the sort of evidence that they would never have been able to adduce on their own. The order has been issued despite the fact that the Allahabad High Court reserved its order on the maintainability of the suit on March 15 and is yet to pronounce its ruling. It is not clear why the civil judge did not wait for the ruling and went ahead with his directive to the ASI. By an order in 1997, the civil court had decided that the suit was not barred by the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which said all pending suits concerning the status of places of worship will abate and that none can be instituted. -

The First National Conference Government in Jammu and Kashmir, 1948-53

THE FIRST NATIONAL CONFERENCE GOVERNMENT IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR, 1948-53 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY BY SAFEER AHMAD BHAT Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ISHRAT ALAM CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2019 CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I, Safeer Ahmad Bhat, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, certify that the work embodied in this Ph.D. thesis is my own bonafide work carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Ishrat Alam at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. The matter embodied in this Ph.D. thesis has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. I declare that I have faithfully acknowledged, given credit to and referred to the researchers wherever their works have been cited in the text and the body of the thesis. I further certify that I have not willfully lifted up some other’s work, para, text, data, result, etc. reported in the journals, books, magazines, reports, dissertations, theses, etc., or available at web-sites and included them in this Ph.D. thesis and cited as my own work. The manuscript has been subjected to plagiarism check by Urkund software. Date: ………………… (Signature of the candidate) (Name of the candidate) Certificate from the Supervisor Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge. Prof. Ishrat Alam Professor, CAS, Department of History, AMU (Signature of the Chairman of the Department with seal) COURSE/COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION/PRE- SUBMISSION SEMINAR COMPLETION CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. -

A Hundred Years of Tagore in Finland

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVII (2015) 10.12797/CIS.17.2015.17.08 Klaus Karttunen [email protected] (University of Helsinki) A Hundred Years of Tagore in Finland Summary: The reception of Rabindranath Tagore in Finland, starting from newspa- per articles in 1913. Finnish translations of his works (19 volumes in 1913–2013, some in several editions) listed and commented upon. Tagore’s plays in theatre, radio and TV, music composed on Tagore’s poems. Tagore’s poem (Apaghat 1929) commenting upon the Finnish Winter War. KEYWORDS: Rabindranath Tagore, Bengali Literature, Indian English Literature, Fin nish Literature. In Finland as well as elsewhere in the West, the knowledge of Indian literature was restricted to a few Sanskrit classics until the second decade of the 20th century. The Nobel Prize in Literature given to Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) in 1913 changed this at once. To some extent, the importance of Tagore had been noted even before—the Swedish Nobel Committee did not get his name out of nowhere.1 Tagore belonged to a renowned Bengali family and some echoes of this family had even been heard in Finland. As early as the 1840s, 1 The first version of this paper was read at the International Tagore Conference in Halle (Saale), Germany, August 2–3, 2012. My sincere thanks are due to Hannele Pohjanmies, the translator of Tagore’s poetry, who has also traced many details about the history of the poet in Finland. With her kind permission, I have used this material, supplementing it from newspaper archives and from my own knowledge. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan)