Inter-War, Inter-Service Friction on the North-West Frontier of India and Its Impact on the Development and Application of Royal Air Force Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 104 – July 2020

THE TIGER Homes for heroes by the sea . THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 104 – JULY 2020 CHAIRMAN’S COLUMN Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to The Tiger. Whilst the first stage of the easing of the “lockdown” still prevent us from re-uniting at Branch Meetings, there is still a certain amount of good news emanating from the “War Front”. In Ypres, from 1st July, members of the public will be permitted to attend the Last Post Ceremony, although numbers will be limited to 152, with social distancing of 1.5 metres observed. 1st July will also see the re-opening of Talbot House in Poperinghe. Readers will be pleased to learn that the recent fund-raising appeal for the House, featured in this very column in the May edition of The Tiger reached its required target and my thanks go to those of you who donated to this worthy cause. Another piece of news has, as yet, received scant publicity but could prove to be the most important of all. In the aftermath of the recent “attack” on the Cenotaph, during which an attempt was made to set alight our national flag, I was delighted to read in the Press that: a Desecration of War Memorials Bill, carrying a ten year prison sentence, would be brought before the Commons as a matter of urgency. The subsequent discovery that ten years was the maximum sentence rather than the minimum tempered my joy somewhat, but the fact that War Memorials are now finally to be legally placed on a higher plane than other statuary is, at least in my opinion, a major step forward in their protection. -

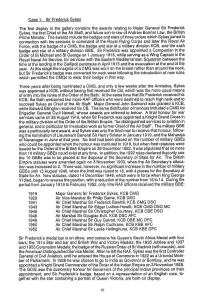

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020 The Dissertation Committee for John Michael Meyer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation. One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) Committee: Ami Pedahzur, Supervisor Zoltan D. Barany David M. Buss William Roger Louis Thomas G. Palaima Paul B. Woodruff One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) by John Michael Meyer Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Dedication To Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis who guided me on this endeavor from start to finish and To Lorna Paterson Wingate Smith. Acknowledgements Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis have helped me immeasurably throughout my time at the University of Texas, and I wish that everyone could benefit from teachers so rigorous and open minded. I will never forget the compassion and strength that they demonstrated over the course of this project. Zoltan Barany developed my skills as a teacher, and provided a thoughtful reading of my first peer-reviewed article. David M. Buss kept an open mind when I approached him about this interdisciplinary project, and has remained a model of patience while I worked towards its completion. My work with Tom Palaima and Paul Woodruff began with collaboration, and then moved to friendship. Inevitably, I became their student, though they had been teaching me all along. -

Staffp2facts May06

STAFF CADET PART II FACT SHEET HQ Kent Wing Air Training Corps Yeomanry Cottages, Boxley Road, Maidstone, Kent ME14 2AR Officer Commanding Wing Commander A. Atkins RAFVR(T) Wing Administrative Officer Squadron Leader R. Bushby RAFR (Including co-ordination of Camps and AEF) Wing Hon Chairman Squadron Leader R. E. Fawkes RAFVR(T) (Retd) Wing Chaplain Reverend D. Barnes Squadrons: 36 Staff Numbers: Officers: 63; Adult SNCOs: 68; Civilian Instructors 146 (correct at 20-Mar-06) Number of Cadets: 1115 enrolled and probationers (correct at 30-Sep-05) Wing Staff and Duties (as at 01-Jan-05) Post Duties WSO1 Squadron Leader V. R. Beaney RAFVR(T) Deputy Adventure Training Technical Officer, BELA Course Director, Duke of Edinburgh’s Award & Area 1 Staff Officer WSO2 Squadron Leader C. Hatton RAFVR(T) Gliding Liaison, Health and Safety, Airshows, Aircraft Recognition, Aeromodelling, AWO/Adult SNCO Liaison & Area 2 Staff Officer WSO3 Squadron Leader B. J. Fitzpatrick RAFVR(T) Classification and Syllabus Training (inc. BTECs), Pre-Adult and Adult Training Courses, Marconi-Elliott and Clarke Competitions, Bands & Area 3 Staff Officer WSO4 Squadron Leader R. C. Goodayle RAFVR(T) Deputy OC Wing, Adventure Training Technical Officer, Green Camps and ACF Liaison, PMC, Pentathlon & Area 4 Staff Officer WSO5 Flight Lieutenant D. C. Horsley RAFVR(T) Corporate Communications, Radio Communications, Flying Development and Flying Opportunities, Work Experience and Station Visits, Elworthy Trophy & Special Projects WSO6 Squadron Leader P. Atkins RAFVR(T) Cadet NCO Training Courses, Adult and Cadet First Aid Training, Techniques of Instruction, Nijmegen, Overseas Visits & Sun’n’Fun WWO AWO H. Hollamby Area Warrant Officers Wing Duties Performed by Squadron Staff Shooting Flight Lieutenant M. -

Suez 1956 24 Planning the Intervention 26 During the Intervention 35 After the Intervention 43 Musketeer Learning 55

Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd i 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East Louise Kettle 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiiiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Louise Kettle, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/1 3 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3795 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3797 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3798 1 (epub) The right of Louise Kettle to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iivv 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. Learning from History 1 Learning from History in Whitehall 3 Politicians Learning from History 8 Learning from the History of Military Interventions 9 How Do We Learn? 13 What is Learning from History? 15 Who Learns from History? 16 The Learning Process 18 Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 21 2. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

A M D G Beaumont Union Review Summer 2020

A M D G BEAUMONT UNION REVIEW SUMMER 2020 "And I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year: ―Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.‖ Well, we didn‘t see this one coming. Having written in the last REVIEW about ―a year like no other‖ which concludes in this Edition, no one thought we would be living through another. Over 90% of the BU have been confined and we have seen the cancellation of The HCPT and BOFs Pilgrimage to Lourdes, The Verdun Battlefield Tour, The BUGS Meeting at Westerham and Ant Stevens much anticipated Musical ―Streetwise‖: Now rescheduled for 24-29 May 2021. Much quoted at the moment ―We will meet again, Don‘t know where, Don‘t know when but I know we will meet again some sunny day: - Actually it looks like a cloudy day in the Autumn if we are lucky! I was amazed by the response to my Easter Message: I don‘t know whether it could be described as an ―Urbi et Orbi‖ moment but it did bring a huge response from OBs worldwide. One such from Patrick Agnew which I share with you:- ―Indeed. We have taken a lot for granted, during our years; much to be grateful for. Humanity is vulnerable to many things, some much worse than seen now. Globalization has it‘s many drawbacks, as well. Our precious little planet, in such perfect evolved balance, for so many eons, is also threatened by the economic ―progress‖ of mankind, whose numbers compound upwards and ravage resources, and are poisoning them. -

Churchill, Wavell and Greece, 1941*

Robin Higham Duty, Honor and Grand Strategy: Churchill, Wavell and Greece, 1941* In our previous works, then Capt. Harold E. Raugh and I took too limited a Mediterranean view of the background of the Greek campaign of 6-26 April 19411. Far from its being Raugh’s “disastrous mistake,” I argue that General Sir Archibald Wavell’s actions fitted both traditional British practice and the general policy worked out in London. In 1986 and 1987 I argued after long and careful thought since 1967 that Wavell went to Greece as part of a loyal deception of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, whose bellicose way at war was the antithesis of Wavell’s own professionalism. Further, whereas Raugh took the narrow military view, mine was a grand-strategic approach relating ends to means. My argument here is that a restudy of the campaign in Greece of 6-27 April 1941 utilizing the Orange Leonard ULTRA messages reconfirms my thesis that going to Greece was a deception and that far from being the miserable defeat which Raugh imagined, the withdrawal was a strategic triumph in the manner of a Wellington in Spain and Portugal or of the BEF’s in France in 1940. For this Wavell deserves full credit. In this respect, then, the so-called campaign in Greece must be seen not as an ignominious retreat in the face of superior forces, but rather as a skilful, carefully planned withdrawal and ultimate evacuation. It was a successful, though materially costly, gamble. * This paper was accepted for publication in late 2005 but delayed by the Balkan Studies financial crisis. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

The Rhodesian Crisis in British and International Politics, 1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE RHODESIAN CRISIS IN BRITISH AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS, 1964-1965 by CARL PETER WATTS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham April 2006 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis uses evidence from British and international archives to examine the events leading up to Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 11 November 1965 from the perspectives of Britain, the Old Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), and the United States. Two underlying themes run throughout the thesis. First, it argues that although the problem of Rhodesian independence was highly complex, a UDI was by no means inevitable. There were courses of action that were dismissed or remained under explored (especially in Britain, but also in the Old Commonwealth, and the United States), which could have been pursued further and may have prevented a UDI. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 14 AUGUST, 1946 4097 Shortly Afterwards Our Troops Took Possession Eamichliye to a Point Where the Road Mosul- of the Town

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 14 AUGUST, 1946 4097 shortly afterwards our troops took possession Eamichliye to a point where the road Mosul- of the town. The railway and all railway in- Deir-ez-Zor crosses the Iraq-Syria frontier. .stallations up to the Turkish frontier had -been (iii) Lt. General Quinan was to submit captured intact as well as several bridges which his plans for holding the Northern Frontier had .been prepared for demolition. of Iraq against hostile advance through On 8th July, a column was sent to capture Anatolia or Iran. The construction of per- Hassetche, the seat of the local Government, manent defences in this area was to be con- in the Bee du Canard. Here the French de- fined to denying, where possible, the main cided not to fight and the town and fort were • lines of approach by armoured fighting occupied without opposition. vehicles into Iraq from Turkey or Iran with On gth July Ras el Ain was found to be the object of slowing up an advance and clear of French troops. Lack of motor trans- forcing it into unsuitable country. Plans in port made furtiher advance impossible. 5th detail were also to be prepared for an ad- Battalion I3th Frontier Force Rifles therefore vance into Turkish or Iranian territory in remained in occupation of the Bee du Canard order to seize defiles suitable for delaying covering the railway and the remainder of the action and to carry out extensive demoli- column returned to Mosul on I4th July. tions. 26. On return, of the Headquarters of I7th (iv) A suitable force was to be held in Indian Infantry Brigade to Mosul, the Head- readiness to enable the occupation of quarters of the aoth Indian Infantry Brigade Abadan and Naft-i-Shah to be carried out at moved to Baghdad, being better placed there short notice. -

British 8Th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-1918

Centre for First World War Studies British 8th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-18 by Alun Miles THOMAS Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law January 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Recent years have seen an increasingly sophisticated debate take place with regard to the armies on the Western Front during the Great War. Some argue that the British and Imperial armies underwent a ‘learning curve’ coupled with an increasingly lavish supply of munitions, which meant that during the last three months of fighting the BEF was able to defeat the German Army as its ability to conduct operations was faster than the enemy’s ability to react. This thesis argues that 8th Division, a war-raised formation made up of units recalled from overseas, became a much more effective and sophisticated organisation by the war’s end. It further argues that the formation did not use one solution to problems but adopted a sophisticated approach dependent on the tactical situation.