The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

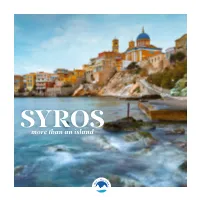

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

(1822 -1833) the First Missionaries Sent By

THE GREEK PRESS AT MALTA OF THE AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSIONS (1822 -1833) The first missionaries sent by the American Board of Commis sioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) to their Western Asia or Mediterranean Mission (the area which included the Mission to the Greeks) were the Reverends Pliny Fisk (1792-1825) and Levi Parsons (1792-1822). They left Boston, the Headquarters of the ABCFM, on November 3, 1819 aboard the ship Sally Ann and reached Smyrna in January of 18201. On December 23, 1819 their ship stopped at Malta which was dt the time the center of activity of the English Protestant missionaries, and there they met the Reverend William Jowett, the representative of the Church Missionary Society, the Reverend Samuel Sheridan Wilson, representative of the London Missionary Society and Dr. Cleardo Naudi, a native of Malta and active in the Bible Society which was formed there,by the British missionaries in 1817. These gen tlemen gave the American missionaries information and letters of introduction to influential people in Smyrna and Chios. When they arrived at Smyrna on January 15, 1820 they met the Rever end Charles Williamson, Episcopal minister and chaplain to the British Consulate and to the Levant Company's factory there.2 After discussing their purpose with Reverend Williamson they decided that Smyrna had many advantages to offer for missionary 1. Accounts of their missionary Clogg (I) p. 177-193. activities are to be found in Alvan 2. For information on Williamson Bond, Memoir of the Rev. Pliny and the activities of the Bible So Fisk, A.M. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Archaeology in the community - educational aspects: Greece: a case-study Papagiannopoulos, Konstantinos How to cite: Papagiannopoulos, Konstantinos (2002) Archaeology in the community - educational aspects: Greece: a case-study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4630/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Konstantinos Papagiannopoulos Archaeology in the community - educational aspects. Greece: a case-study (Abstract) Heritage education in Greece reproduces and reassures the individual, social and national sel£ My purpose is to discuss the reasons for this situation and, by giving account of the recent developments in Western Europe and the new Greek initiatives, to improve the study of the past using non-traditional school education. In particular, Local History projects through the Environmental Education optional lessons allow students to approach the past in a more natural way, that is through the study of the sources and first hand material. -

Περίληψη : Γενικές Πληροφορίες Area: 84.069 Km2

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Κέκου Εύα , Σπυροπούλου Βάσω Μετάφραση : Easthope Christine , Easthope Christine , Ντοβλέτης Ονούφριος (23/3/2007) Για παραπομπή : Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Μαυροειδή Μαρία , Κέκου Εύα , Σπυροπούλου Βάσω , "Syros", 2007, Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Περίληψη : Γενικές Πληροφορίες Area: 84.069 km2 Coastline length: 84 km Population: 19,782 Island capital and its population: Hermoupolis (11,799) Administrative structure: Region of South Aegean, Prefecture of the Cyclades, Municipality of Hermoupolis (Capital: Hermoupolis, 11,799), Municipality of Ano Syros (Capital: Ano Syros, 1,109), Municipality of Poseidonia (Capital: Poseidonia, 633) Local newspapers: Koini Gnomi, Logos, Apopsi Local journals and magazines: Serious Local radio stations: Media 92 (92.0), Radio Station of the Metropolis of Syros (95.4), Aigaio FM (95.4), Syros FM 100.3 (100.3), FM 1 (101.0), Faros FM (104.0), Super FM (107.0) Local TV stations: Syros TV1, Aigaio TV Museums: Syros Archaeological Museum, Historical Archive (General State Archives), Art Gallery "Hermoupolis", Hermoupolis Municipal Library, Cyclades Art Gallery, Industrial Museum of Syros, Historical Centre of the Catholic Church of Syros, Historical Archive of the Municipality of Ano Syros, Marcos Vamvakaris Museum, Ano Syros Museum of Traditional Professions Archaeological sites and monuments: Chalandriani, Kastri, Grammata, Miaoulis Square at Hermoupolis, Hermoupolis Town Hall, Hellas -

The Evangelization of the Ottoman Christians in Western Anatolia in the Nineteenth Century Merih Erol*

“All We Hope is a Generous Revival”: The Evangelization of the Ottoman Christians in Western Anatolia in the Nineteenth Century Merih Erol* “Bütün Ümidimiz Cömert Bir Uyanış”: On Dokuzuncu Yüzyılda Batı Anadolu’da Os- manlı Hıristiyanlarının Evanjelizasyonu Öz Bu makalenin konusu 1870 ve 1880’li yıllarda American Board of Commis- sioners for Foreign Missions adlı misyonerlik örgütünün Batı Türkiye Misyonu adlı biriminin kapsamındaki Manisa ve İzmir istasyonlarında yürüttüğü faaliyetler ve bu bölgedeki Rum ve Ermenilere İncil’in mesajını öğretme çabalarıdır. Esas kaynaklar olarak Amerikalı Protestan misyoner Marcellus Bowen’ın 1874-1880 yılları arasın- da Manisa’dan Boston’daki ana merkeze ve Yunanistan kökenli Protestan misyoner George Constantine’in 1880-1889 yılları arasında İzmir’den Boston’a gönderdikleri mektuplar kullanılmıştır. Bu birinci şahıs anlatımlar olguları ve olayları anında ve doğrudan yorumladıkları için çok zengin bir malzeme sunarlar. Bu çalışma, Ameri- kalı misyonerlerin faaliyetlerini İzmir’in çokkültürlü ve çokuluslu toplumuna uyar- lama çabalarını, bölgede yaşayan Rumlara ve Ermenilere vaaz verirken ya da onlara ibadet için seslenirken hangi dilin kullanılması gerektiği konusundaki kanaatlerini ve gerekçelerini, Protestan misyonerlere muhalefet eden İzmir’deki Rum Ortodoks yüksek rütbeli ruhbanlarının başvurduğu yolları ve dini kitap satma, okul ve kilise açma/yapma eylemlerinin Osmanlı yetkililerince hangi şartlara bağlandığını ve yet- kililerin engelleriyle karşılaştıklarında misyonerlerin hangi aracılara başvurduklarını incelemektedir. Anahtar kelimeler: İzmir, Anadolu’da misyonerlik faaliyetleri, Ermeni ve Rum Pro- testanlar, mezhep/din değiştirme, on dokuzuncu yüzyıl. * Özyeğin University. Osmanlı Araştırmaları / The Journal of Ottoman Studies, LV (2020), 243-280 243 “ALL WE HOPE IS A GENEROUS REVIVAL” Introduction Smyrna/İzmir was the first mission station of the American Board of Com- missioners for Foreign Missions in Ottoman Turkey.1 Yet the British Protestants’ arrival in the city was earlier. -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 8, 2011 Establishing the Discipline of Classical Philology in Nineteenth-century Greece Matthaiou Sophia Institute for Neohellenic Research/ NHRF http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/hr.279 Copyright © 2011 To cite this article: Matthaiou, S. (2012). Establishing the Discipline of Classical Philology in Nineteenth-century Greece. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 8, 117-148. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/hr.279 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 12/12/2018 10:14:06 | ESTABLISHING THE DISCIPLINE OF CLASSICAL PHILOLOGY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY GREECE Sophia Matthaiou Abstract: This paper outlines the process of establishing the discipline of classical philology in Greece in the nineteenth century. During the period shortly before the Greek War of Independence, beyond the unique philological expertise of Adamantios Korais, there is additional evidence of the existence of a fledging academic discussion among younger scholars. A younger generation of scholars engaged in new methodological quests in the context of the German school of Alterthumswissenschaft. The urgent priorities of the new state and the fluidity of scholarly fields, as well as the close association of Greek philology with ideology, were some of the factors that determined the “Greek” study of antiquity during the first decades of the Greek state. The rise of classical philology as an organized discipline during the nineteenth century in Greece constitutes a process closely associated with the conditions under which the new state was constructed. This paper will touch upon the conditions created for the development of the discipline shortly before the Greek War of Independence, as well as on the factors that determined its course during the first decades of the Greek State.1 Although how to precisely define classical philology as an organized discipline is subject to debate, our basic frame of reference will be the period’s most advanced “school of philology”, the German school. -

Ascsa Ar 94 (1974-1975)

AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS FouNDED 1881 Incorporated under the Laws of Massachusetts, 1886 NINETY-FOURTH ANNUAL REPORT 1974-1975 AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STIJDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1 9 7 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ARTICLES OF I NCORPORATION 4 BoARD oF T RuSTEES • 5 MANAGING C OMMITTEE 7 CoMMITTEES OF THE MANAGING CoMMITTEE 15 STAFF OF THE SCHOOL 16 CouNCIL OF THE ALUMNI AssociATION 18 THE AuxiLIARY FuND AssociATION 18 C ooPERATING INSTITUTIONS 19 REPORTS: Director 21 Librarian of the School 27 Director of the Gennadius Library . 28 Professor of Archaeology 34 Field Director of the Agora Excavations 36 Field Director of the Corinth Excavations 40 Special Research Fellows: Visiting Professors 43 Chairman of the Committee on Admissions and Fellowships 47 Director of Summer Session I . 50 Director of Summer Session II 52 Chairman of the Committee on Publications 56 Report of the Auxiliary Fund Association . 65 Report of the Treasurer 66 The Alumni Association . 75 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY J· H. FURST COMPANY, BALTIMORE, MARYLAND ARTICLES OF INCORPORATION AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS AT ATHENS BE IT KNowN WHEREAS James R. Lowell, T. D. Woolsey, Charles Eliot Norton, William M. Sloane, B. L. Gildersleeve, William W. Goodwin, Henry BOARD OF TRUSTEES 197~1975 Drisler, Frederic J. de Peyster, John Williams White, Henry G. Marquand and Martin Brimmer, have associated themselves with the intention of forming Joseph Alsop ....•.....•.. ..• 2720 Dumbarton Avenue, Washington, a corporation under the name of the District of Columbia John Nicholas Brown .•• . • . ...• . SO South Main Street, Providence, Rhode Island TRUSTEES OF THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL Frederick C. -

06 4 1979.Pdf

VOL. VI, No. 4 WINTER 1979 Editorial Board: DAN GEORGAKAS PASCHALIS M. KITROMILIDES PETER PAPPAS YIANNIS P. ROUBATIS Advisory Editors: Nucos PETROPOULOS DINO SIOTIS The Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora air mail; Institutional—$20.00 for one is a quarterly review published by Pella year, $35.00 for two years. Single issues Publishing Company, Inc., 461 Eighth cost $3.50; back issues cost $4.50. Avenue, New York, NY 10001, U.S.A., in March, June, September, and Decem- Advertising rates can be had on request ber. Copyright © 1979 by Pella Publish- by writing to the Managing Editor. ing Company. Articles appearing in this Journal are The editors welcome the freelance sub- abstracted and/or indexed in Historical mission of articles, essays and book re- Abstracts and America: History and views. All submitted material should be Life; or in Sociological Abstracts; or in typewritten and double-spaced. Trans- Psychological Abstracts; or in the Mod- lations should be accompanied by the ern Language Association Abstracts (in- original text. Book reviews should be cludes International Bibliography) in approximately 600 to 1,200 words in accordance with the relevance of content length. Manuscripts will not be re- to the abstracting agency. turned unless they are accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All articles and reviews published in Subscription rates: Individual—$12.00 the Journal represent only the opinions for one year, $22.00 for two years; of the individual authors; they do not Foreign—$15.00 for one year by surface necessarily reflect the views of the mail; Foreign—$20.00 for one year by editors or the publisher NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS MARIOS L. -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Documentation Centre - EKT journals The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 8, 2011 Establishing the Discipline of Classical Philology in Nineteenth-century Greece Matthaiou Sophia Institute for Neohellenic Research/ NHRF https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.279 Copyright © 2011 To cite this article: Matthaiou, S. (2012). Establishing the Discipline of Classical Philology in Nineteenth-century Greece. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 8, 117-148. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.279 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 09:06:11 | ESTABLISHING THE DISCIPLINE OF CLASSICAL PHILOLOGY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY GREECE Sophia Matthaiou Abstract: This paper outlines the process of establishing the discipline of classical philology in Greece in the nineteenth century. During the period shortly before the Greek War of Independence, beyond the unique philological expertise of Adamantios Korais, there is additional evidence of the existence of a fledging academic discussion among younger scholars. A younger generation of scholars engaged in new methodological quests in the context of the German school of Alterthumswissenschaft. The urgent priorities of the new state and the fluidity of scholarly fields, as well as the close association of Greek philology with ideology, were some of the factors that determined the “Greek” study of antiquity during the first decades of the Greek state. The rise of classical philology as an organized discipline during the nineteenth century in Greece constitutes a process closely associated with the conditions under which the new state was constructed. -

Aspects of Rendering the Sacred Tetragrammaton in Greek

Open Theology 2014; Volume 1: 56–88 Research Article Open Access Pavlos D. Vasileiadis Aspects of rendering the sacred Tetragrammaton in Greek Abstract: This article recounts the persistent use of the sacred Tetragrammaton through the centuries as an „effable,“ utterable name at least in some circles, despite the religious inhibitions against its pronunciation. A more systematic investigation of the various Greek renderings of the biblical name of God is provided. These renderings are found in amulets, inscriptions, literary works, etc., dating from the last few centuries B.C.E. until today. It will be illustrated that some forms of the Tetragrammaton were actually accepted and used more widely within the Greek religious and secular literature since the Renaissance and especially since the Modern Greek Enlightenment. Furthermore, it is asserted that for various reasons there is no unique or universally “correct” rendering of the Hebrew term in Greek. Of special note are two Greek transcriptions of the Tetragrammaton, one as it was audible and written down by a Greek-speaking author of a contra Judaeos work in the early 13th century in South Italy and another one written down at Constantinople in the early 17th century—both of them presented for the first time in the pertinent bibliography. Keywords: Tetragrammaton, Greek Bible, Divine names theology, Bible translations, Biblical God. DOI 10.2478/opth-2014-00061 Received August 3, 2014; accepted October 8, 2014 Introduction The name of God has always“ ,(יְהֹוָה) or Jehovah (יַהְוֶה) commonly pronounced Yahweh ,(יהוה .The sacred Tetragrammaton (Heb been regarded as the most sacred and the most distinctive name of God,” it is “His proper name par excellence.” This name holds the most prominent status within the Hebrew Scriptures in comparison to other appellations or titles attributed to God. -

RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS 2004-2010 MONOGRAPHS Ioli Vigopoulou, Le Monde Grec Vu Par Les Voyageurs Du Xvie Siècle, IRN/FNRS, Collec

1 RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS 2004-2010 MONOGRAPHS Ioli Vigopoulou, Le monde grec vu par les voyageurs du XVIe siècle, IRN/FNRS, Collection "Histoire des Idées" - 4, Athens 2004, 514 p. The central theme of this study is the Greeks’ economic activities and their daily life, as seen through the eyes and works of travellers of the 16th century, and as these subjects were recognized, recorded and published for the reading public. Its main axis is the critical treatment of the testimonies and not a simple record of information. For the purposes of this study, a 16th century travelogue is considered to be the written chronicle by any traveller who traversed the land or recounted data and events in the areas where there were Greeks in the period under scrutiny. 115 such travellers were selected, from the third decade of the 15th century until the early 17th. All the travellers and their texts are compared with Pierre Belon, as much for the traveller-figure as in regard to his product-chronicle. The main axis of the approach to the sources was the necessary filtering of descriptive testimonies, having as parameters the subjective character on the one hand of each traveller and text, and on the other hand the objective conditions of writing and provision of these data. It begins with introducing the persons-travellers and continues with the treatment by the traveller of the experience of the journey, the perception of the area and population distribution. There follows an analysis of the testimonies on the economic activities of Greeks (agriculture, stock breeding, fishing, mining, trade), daily life (occupations- professions, dwelling, clothing, nutrition, customs and manners, the women) and general judgements of their conduct and religious faith.