Itineraries in the World of the Enlightenment. Adamantios Korais from Smyrna Via Montpellier to Paris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Greek Enlightenment and the Changing Cultural Status of Women

SOPHIA DENISSI The Greek Enlightenment and the Changing Cultural Status of Women In 1856 Andreas Laskaratos, one of the most liberal authors of his time, writes: There is no doubt that we took a giant step in allowing our women learning. This step reveals that a revolution took place in the spirit; a revolution which has taken our minds away from the road of backwardness and has led them to the road of progress. Though this transmission has not received any attention yet, it constitutes one of these events that will leave its trace in the history of the human spirit.1 Laskaratos is quite correct in talking about a revolution since the decision to accept women's education at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries was indeed a revolutionary act if we consider the state of Greek women who had been living in absolute ignorance and seclusion that prevailed throughout the years of the Ottoman occupation. What caused this revolution? What made Greek men, or rather a progressive minority at first, still subjects of the Ottoman Empire concede the right to education and even to a public voice for women? The answer will be revealed to us by taking a close look at the first educated Greek women who managed to break the traditional silence imposed upon their sex by patriarchal culture and make their presence felt in the male world. We can distinguish two main groups among the first educated Greek women; those coming from the aristocratic circle of the Phanariots and those coming from the circle of progressive men of letters. -

The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864

1 Constructing Ionian Identities: The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864 Maria Paschalidi Department of History University College London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to University College London 2009 2 I, Maria Paschalidi, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Utilising material such as colonial correspondence, private papers, parliamentary debates and the press, this thesis examines how the Ionian Islands were defined by British politicians and how this influenced various forms of rule in the Islands between 1815 and 1864. It explores the articulation of particular forms of colonial subjectivities for the Ionian people by colonial governors and officials. This is set in the context of political reforms that occurred in Britain and the Empire during the first half of the nineteenth-century, especially in the white settler colonies, such as Canada and Australia. It reveals how British understandings of Ionian peoples led to complex negotiations of otherness, informing the development of varieties of colonial rule. Britain suggested a variety of forms of government for the Ionians ranging from authoritarian (during the governorships of T. Maitland, H. Douglas, H. Ward, J. Young, H. Storks) to representative (under Lord Nugent, and Lord Seaton), to responsible government (under W. Gladstone’s tenure in office). All these attempted solutions (over fifty years) failed to make the Ionian Islands governable for Britain. The Ionian Protectorate was a failed colonial experiment in Europe, highlighting the difficulties of governing white, Christian Europeans within a colonial framework. -

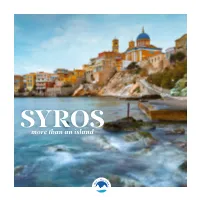

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

200Th Anniversary of the Greek War of Independence 1821-2021 18 1821-2021

Special Edition: 200th Anniversary of the Greek War of Independence 1821-2021 18 1821-2021 A publication of the Dean C. and Zoë S. Pappas Interdisciplinary March 2021 VOLUME 1 ISSUE NO. 3 Center for Hellenic Studies and the Friends of Hellenic Studies From the Director Dear Friends, On March 25, 1821, in the city of Kalamata in the southern Peloponnesos, the chieftains from the region of Mani convened the Messinian Senate of Kalamata to issue a revolutionary proclamation for “Liberty.” The commander Petrobey Mavromichalis then wrote the following appeal to the Americans: “Citizens of the United States of America!…Having formed the resolution to live or die for freedom, we are drawn toward you by a just sympathy; since it is in your land that Liberty has fixed her abode, and by you that she is prized as by our fathers.” He added, “It is for you, citizens of America, to crown this glory, in aiding us to purge Greece from the barbarians, who for four hundred years have polluted the soil.” The Greek revolutionaries understood themselves as part of a universal struggle for freedom. It is this universal struggle for freedom that the Pappas Center for Hellenic Studies and Stockton University raises up and celebrates on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the beginning of the Greek Revolution in 1821. The Pappas Center IN THIS ISSUE for Hellenic Studies and the Friends of Hellenic Studies have prepared this Special Edition of the Hellenic Voice for you to enjoy. In this Special Edition, we feature the Pappas Center exhibition, The Greek Pg. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Ahif Po L I C Y J O U R N

AHIF P O L I C Y J O U R N A L Spring 2015 Kapodistrias and the Making of Modern Europe and Modern Greece Patrick Theros n 1998, Theodoros Pangalos, Greece’s Foreign Minister attended an EU Conference of I otherwise little note in Brussels. He was half asleep during the sessions until the then President of the Dutch Parliament rose to speak about the common European heritage. The Dutchman proclaimed that a common cultural history united Europe: beginning with feudalism, followed by the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Counter- reformation, the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. This history differentiated Europeans from non-Europeans, a category which the unctuous Dutchman obviously deemed unworthy of membership. Pangalos suddenly came awake and leaped to his feet to state, in his normal colorful fashion, that the Dutchman had just insulted Greece. Greece had indeed lived through feudalism. It had come to Greece in the form of the Fourth Crusade, the sacking of Constantinople, and the dismembering of the country that virtually depopulated Greece. Pangalos apparently went on to eviscerate the Dutchman. He described the Renaissance as created by Greek scholars who fled the Turkish conquest. As for the Reformation and Counter Reformation; those were internal civil wars of the Papacy. No one seems to have memorialized Pangalos’ comments on the Enlightenment and the French Revolution as his Greek diplomats cringed and mostly tried to quiet him down. Pangalos’ ranting was more or less on point and, in fact, historically quite accurate. But the EU officials present, locked into the notion that Western civilization (quite narrowly defined) provided the gold standard for the world to try to emulate while the history and culture of others rated only academic interest made fun of Pangalos to the other Greeks present. -

Iosipos Moesiodax – Un Dascăl Din Secolul Al Xviii-Lea Și Concepția Sa Privind Cunoașterea

IOSIPOS MOESIODAX – UN DASCĂL DIN SECOLUL AL XVIII-LEA ȘI CONCEPȚIA SA PRIVIND CUNOAȘTEREA DRAGOȘ POPESCU* I OSIPOS M OESIODAX – AN 18TH-CENTURY S CHOLAR AND HIS V IEW ON K NOWLEDGE A BSTRACT: The following article presents the life and work of Josip Moesiodax (1725–1800), a professor at the Princely Academies in Bucharest and Iasi in the latter part of the 18th century. Representative of the Enlightenment, Moesiodax encouraged the natural sciences and regarded the Neo-Aristotelianism that prevailed in the Balkan scholarship as the main source of stagnation of knowledge in the Ottoman Empire. He argued for the replacement of the Aristotelian metaphysics with mathematics as a basic discipline in school as well as for the simplification of scientific terminology. He is the author of Apology (1781) and Pedagogy (1779), two significant works of that age. K EYWORDS: Neo-Aristotelianism; Princely Academies of Bucharest and Iasi; experimental science; Enlightement; Iosipos Moesiodax. INTRODUCERE În secolul al XVIII-lea, în Moldova și Țara Românească administrate de domnitorii fanarioți, învățământul superior (cu excepția celui teologic) se desfășura la Academiile Domnești din Iași și București. Lecțiile se țineau în limba greacă, spre deosebire de universitățile apusene, unde limba de predare era latina. La acea vreme, alegerea limbii de predare în instituțiile de învățământ superior, de-a lungul și de-a latul continentului, nu presupunea prea multe opțiuni: marile texte filosofice și științifice (datând din Antichitate), ca și comentariile lor autorizate (redactate în Antichitatea târzie sau Evul Mediu), erau disponibile în greacă și latină și făceau obligatorie, în prealabil, achiziționarea acestor limbi. -

By Konstantinou, Evangelos Precipitated Primarily by the Study

by Konstantinou, Evangelos Precipitated primarily by the study of ancient Greece, a growing enthusiasm for Greece emerged in Europe from the 18th century. This enthusiasm manifested itself in literature and art in the movements referred to as classicism and neoclassicism. The founda- tions of contemporary culture were identified in the culture of Greek antiquity and there was an attempt to learn more about and even revive the latter. These efforts manifested themselves in the themes, motifs and forms employed in literature and art. How- ever, European philhellenism also had an effect in the political sphere. Numerous societies were founded to support the cause of Greek independence during the Greek War of Independence, and volunteers went to Greece to join the fight against the Ottoman Empire. Conversely, the emergence of the Enlightenment in Greece was due at least in part to the Greek students who studied at European universities and brought Enlightenment ideas with them back to Greece. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Literary and Popular Philhellenism in Europe 2. European Travellers to Greece and Their Travel Accounts 3. The Greek Enlightenment 4. Reasons for Supporting Greece 5. Philhellenic Germany 6. Lord Byron 7. European Philhellenism 8. Societies for the Support of the Greeks 9. Bavarian "State Philhellenism" 10. Jakob Philip Fallmerayer and Anti-Philhellenism 11. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Indices Citation The neo-humanism of the 18th and 19th centuries contributed considerably to the emergence of a philhellenic1 climate in Europe. This new movement was founded by Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) (ᇄ Media Link #ab), who identified aesthetic ideals and ethical norms in Greek art, and whose work Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (1764) (ᇄ Media Link #ac) (History of the Art of Antiquity) made ancient Greece the point of departure for an aestheticizing art history and cultural history. -

The Eusebius Lab International Working Papers Series

Series Εργαστήριο Ιστορίας, Πολιτικής, Διπλωματίας και Γεωγραφίας της Εκκλησίας Laboratory of History, Policy, Diplomacy and Geography of the Church Papers The Eusebius Lab International Working Papers Series Eusebius Lab International Working Paper 2020/07 Working The Greek Orthodox Church during the Dictatorship of the Colonels Relations of Church and State in Greece at the seven - year period of military Junta (1967-1974) International Lab Charalampos Μ. Andreopoulos School of Pastoral and Social Theology Eusebius Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Campus GR 54636 Thessaloniki, GREECE http://eusebiuslab.past.auth.gr The ISSN:2585-366X The Greek Orthodox Church during the Dictatorship of the Colonels Relations of Church and State in Greece at the seven - year period of military Junta (1967-1974) Charalampos Μ. Andreopoulos Dr. of Theology AUTH Περίληψη Τό ἐκκλησιαστικό ἦταν τό μοναδικό ἀπό τά θέματα τῆς ζωῆς τοῦ τόπου ὅπου ἡ δικτατορία τῶν Συνταγματαρχῶν εἰς ἀμφότερες τίς φάσεις αὐτῆς (ἐπί Γ. Παπαδοπούλου, 1967-1973 καί ἐπί Δημ. Ἰωαννίδη, 1973-1974) ἐφήρμοσε διαφοροποιημένη πολιτική. Καί στίς δυό περιπτώσεις ὑπῆρχε ἴδια τακτική: Παρέμβαση στά ἐσωτερικά της Ἐκκλησίας τῆς Ἑλλάδος, παραβίαση τῆς κανονικῆς τάξεως (= τῶν ἐκκλησιαστικῶν κανόνων), ἐπιβολή Ἀρχιεπισκόπου τῆς ἐμπιστοσύνης τοῦ κατά περίπτωση πραξικοπηματία (Γ. Παπαδοπούλου-Δ. Ἰωαννίδη), πλαισιωμένου ἀπό δια- φορετική καί παντοδύναμη κάθε φορά ὁμάδα ἀρχιερέων. Κατά τήν πρώτη φάση τῆς δικτατορί- ας ὁ κανονικός καί νόμιμος Ἀρχιεπίσκοπος Χρυσόστομος Β΄ (Χατζησταύρου) ἀρνούμενος -

The Vlachs of Greece and Their Misunderstood History Helen Abadzi1 January 2004

The Vlachs of Greece and their Misunderstood History Helen Abadzi1 January 2004 Abstract The Vlachs speak a language that evolved from Latin. Latin was transmitted by Romans to many peoples and was used as an international language for centuries. Most Vlach populations live in and around the borders of modern Greece. The word „Vlachs‟ appears in the Byzantine documents at about the 10th century, but few details are connected with it and it is unclear it means for various authors. It has been variously hypothesized that Vlachs are descendants of Roman soldiers, Thracians, diaspora Romanians, or Latinized Greeks. However, the ethnic makeup of the empires that ruled the Balkans and the use of the language as a lingua franca suggest that the Vlachs do not have one single origin. DNA studies might clarify relationships, but these have not yet been done. In the 19th century Vlach was spoken by shepherds in Albania who had practically no relationship with Hellenism as well as by urban Macedonians who had Greek education dating back to at least the 17th century and who considered themselves Greek. The latter gave rise to many politicians, literary figures, and national benefactors in Greece. Because of the language, various religious and political special interests tried to attract the Vlachs in the 19th and early 20th centuries. At the same time, the Greek church and government were hostile to their language. The disputes of the era culminated in emigrations, alienation of thousands of people, and near-disappearance of the language. Nevertheless, due to assimilation and marriages with Greek speakers, a significant segment of the Greek population in Macedonia and elsewhere descends from Vlachs. -

Download All Beautiful Sites

1,800 Beautiful Places This booklet contains all the Principle Features and Honorable Mentions of 25 Cities at CitiesBeautiful.org. The beautiful places are organized alphabetically by city. Copyright © 2016 Gilbert H. Castle, III – Page 1 of 26 BEAUTIFUL MAP PRINCIPLE FEATURES HONORABLE MENTIONS FACET ICON Oude Kerk (Old Church); St. Nicholas (Sint- Portugese Synagoge, Nieuwe Kerk, Westerkerk, Bible Epiphany Nicolaaskerk); Our Lord in the Attic (Ons' Lieve Heer op Museum (Bijbels Museum) Solder) Rijksmuseum, Stedelijk Museum, Maritime Museum Hermitage Amsterdam; Central Library (Openbare Mentoring (Scheepvaartmuseum) Bibliotheek), Cobra Museum Royal Palace (Koninklijk Paleis), Concertgebouw, Music Self-Fulfillment Building on the IJ (Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ) Including Hôtel de Ville aka Stopera Bimhuis Especially Noteworthy Canals/Streets -- Herengracht, Elegance Brouwersgracht, Keizersgracht, Oude Schans, etc.; Municipal Theatre (Stadsschouwburg) Magna Plaza (Postkantoor); Blue Bridge (Blauwbrug) Red Light District (De Wallen), Skinny Bridge (Magere De Gooyer Windmill (Molen De Gooyer), Chess Originality Brug), Cinema Museum (Filmmuseum) aka Eye Film Square (Max Euweplein) Institute Musée des Tropiques aka Tropenmuseum; Van Gogh Museum, Museum Het Rembrandthuis, NEMO Revelation Photography Museums -- Photography Museum Science Center Amsterdam, Museum Huis voor Fotografie Marseille Principal Squares --Dam, Rembrandtplein, Leidseplein, Grandeur etc.; Central Station (Centraal Station); Maison de la Berlage's Stock Exchange (Beurs van -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by MUCC (Crossref) The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 13, 2016 The resilience of Philhellenism Tolias George http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/hr.11556 Copyright © 2017 George Tolias To cite this article: Tolias, G. (2017). The resilience of Philhellenism. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 13, 51-70. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/hr.11556 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 12/01/2020 21:33:32 | THE RESILIENCE OF PHILHELLENISM ’Tis Greece, but living Greece no more! So coldly sweet, so deadly fair, We start, for soul is wanting there… Lord Byron, The Giaour, 1813 George Tolias ABStraCT: This essay aims to survey certain key aspects of philhellenism underpinned by the recent and past bibliography on the issue. By exploring the definitions of the related terms, their origins and their various meanings, the paper underscores the notion of “revival” as a central working concept of philhellenic ideas and activities and explores its transformations, acceptances or rejections in Western Europe and in Greece during the period from 1770 to 1870. Philhellenisms “TheF rench are by tradition philhellenes.” With this phrase, the authors of Le Petit Robert exemplified the modern usage of the wordphilhellène , explaining that it denotes those sympathetic to Greece. Although the chosen example refers to a tradition, the noun “philhellene” entered the French vocabulary in 1825 as a historical term which denoted someone who championed the cause of Greek independence. According to the same dictionary, the term “philhellenism” started to be used in French in 1838.