Aspects of Rendering the Sacred Tetragrammaton in Greek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CE:1227A-1228A) HEXAPLA and TETRAPLA, Two Editions of the Old Testament by ORIGEN

(CE:1227a-1228a) HEXAPLA AND TETRAPLA, two editions of the Old Testament by ORIGEN. The Bible was the center of Origen's religion, and no church father lived more in it than he did. The foundation, however, of all study of the Bible was the establishment of an accurate text. Fairly early in his career (c. 220) Origen was confronted with the fact that Jews disputed whether some Christian proof texts were to be found in scripture, while Christians accused the Jews of removing embarrassing texts from scripture. It was not, however, until his long exile in Caesarea (232-254) that Origen had the opportunity to undertake his major work of textual criticism. EUSEBIUS (Historia ecclesiastica 6. 16) tells us that "he even made a thorough study of the Hebrew language," an exaggeration; but with the help of a Jewish teacher he learned enough Hebrew to be able to compare the various Jewish and Jewish-Christian versions of the Old Testament that were extant in the third century. Jerome (De viris illustribus 54) adds that knowledge of Hebrew was "contrary to the spirit of his period and his race," an interesting sidelight on how Greeks and Jews remained in their separate communities even though they might live in the same towns in the Greco-Roman East. Origen started with the Septuagint, and then, according to Eusebius (6. 16), turned first to "the original writings in the actual Hebrew characters" and then to the versions of the Jews Aquila and Theodotion and the Jewish-Christian Symmachus. There is a problem, however, about the next stage in Origen's critical work. -

Frank Moore Cross's Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Classics and Religious Studies Department 2014 Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Crawford, Sidnie White, "Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls" (2014). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 127. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford This paper examines the impact of Frank Moore Cross on the study of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Since Cross was a member of the original editorial team responsible for publishing the Cave 4 materials, his influence on the field was vast. The article is limited to those areas of Scrolls study not covered in other articles; the reader is referred especially to the articles on palaeography and textual criticism for further discussion of Cross’s work on the Scrolls. t is difficult to overestimate the impact the discovery They icturedp two columns of a manuscript, columns of of the Dead Sea Scrolls had on the life and career of the Book of Isaiah . -

Andrew Perrin 2019 David Noel Freedman Award for Excellence

Andrew Perrin 2019 David Noel Freedman Award for Excellence and Creativity in Hebrew Bible Scholarship We are pleased to announce that the 2019 David Noel Freedman Award for Excellence and Creativity in Hebrew Bible Scholarship has been awarded to Andrew Perrin for his paper entitled, “Danielic Pseudepigraphy in/and the Hebrew Scriptures? Remodeling the Structure and Scope of Daniel Traditions at Qumran.” Andrew Perrin (Ph.D Religious Studies, McMaster University, 2013) is Canada Research Chair in Religious Identities of Ancient Judaism and Director of the Dead Sea Scrolls Institute at Trinity Western University in Langley, British Columbia, Canada. His research explores the life, thought, and literature of Second Temple Judaism through the lens of the Dead Sea Scrolls. His book The Dynamics of Dream-Vision Revelation in the Aramaic Dead Sea Scrolls (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015) won the Manfred Lautenschlaeger Award for Theological Promise from the University of Heidelberg. Aspects of his work have been published in Journal of Biblical Literature, Dead Sea Discoveries, Vetus Testamentum, Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha, and Biblical Archaeology Review, with a co-authored article in Revue de Qumran winning the Norman E. Wagner Award from the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies. He has been a fellow of the Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem and of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. He is currently writing a commentary on priestly literature in the Aramaic Dead Sea Scrolls, which was awarded an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The goal of the Freedman Award is to promote excellence and creativity in Hebrew Bible scholarship. -

Sethian Gnosticism by Joan Ann Lansberry

Sethian Gnosticism By Joan Ann Lansberry The label Gnosticism covers a varied group of religious and philosophical movements that existed in the first and second centuries CE. Today, those who consider themselves Gnostics seek transformative awakening from a material-based stupefaction. But back in the early centuries of the Christian Era, gnosticism was quite a hodge-podge of ideas deriving from the Corpus Hermeticum, the Jewish Apocalyptic writings, the Hebrew Scriptures themselves, and particularly Platonic philosophy. There's even some Egyptian texts, the Gospel of the Egyptians and three Steles of Seth. Seth? Is this Egyptian Set or Jewish Seth? Scholars are divided on this subject, but most of them say there is little connection. “Inasmuch as the Gnostic traditions pertaining to Seth derive from Jewish sources, we are led to posit that the very phenomenon of 'Sethian' Gnosticism per se is of Jewish, perhaps pre-Christian, origin.”1 So who is this Seth who features in Sethian Gnosticism? Birger Pearson says: “After examining the magical texts on Seth-Typhon and the Gnostic texts on Seth, I concluded that no relationship existed between Egyptian Seth and Gnostic Seth.”2 He further declares “By the time of the Gnostic literature no Egyptians except magicians worshipped Seth.”3 But were there any magicians who were also gnostics? Pearson continues: “Contrary to his earlier good standing, the Egyptian Seth becomes a demonic figure in the late Hellenistic period. It is inconceivable that Egyptian Seth was tied in with a hero of the Gnostic -

The Jews of Hellenistic Egypt Jews in Egypt Judahites to E

15 April 2019 Septuagint, Synagogue, and Symbiosis: Jews in Egypt The Jews of Hellenistic Egypt Those who escaped the Babylonian advance on Jerusalem, 605‐586 B.C.E. Gary A. Rendsburg Rutgers University Jeremiah 44:1 ַה ָדּ ָב ֙ר ֲא ֶ ֣שׁר ָהָי֣ה ֶ ֽא ִל־יְר ְמָ֔יהוּ ֶ֚אל ָכּל־ ַהְיּ ִ֔הוּדים ַהיֹּ ְשׁ ִ ֖בים ְבּ ֶ ֣אֶר ץ ִמ ְצָ ֑ר ִים Mandelbaum House ַהיֹּ ְשׁ ִ ֤בים ְבּ ִמ ְגדֹּ ֙ל ְוּב ַת ְח ַפּ ְנ ֵ ֣חס ְוּב֔נֹף וּ ְב ֶ ֥אֶרץ ַפּ ְת ֖רוֹס ֵל ֽ ֹאמר׃ April 2019 4 The word which was to Jeremiah, concerning all the Jews who dwell in the land of Egypt, who dwell in Migdol, Tahpanhes, Noph, and the land of Pathros, saying. Judahites to Egypt 600 – 585 B.C.E. Pathros Map of the Persian (Achaemenid) Empire 538 – 333 B.C.E. Bust of the young Alexander the Great (c. 100 B.C.E.) (British Museum) Empire of Alexander the Great (356‐323 B.C.E.) / (r. 336‐323 B.C.E.) 1 15 April 2019 Cartouche of Alexander the Great N L c. 330 B.C.E. D I K A (Louvre, Paris) R S S The Four Successor Kingdoms to Alexander the Great Ptolemies – Alexandria, Egypt (blue) Selecudis – Seleukia / Antioch (golden) Ptolemy Dynasty Jews under Alexander and Ptolemy I 305 B.C.E. – 30 B.C.E. Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 12, Chapter 1 • Ptolemy brought Jews from Judea and Jerusalem to Egypt. Founded by Ptolemy I, • He had heard that the Jews had been loyal to Alexander. -

God Among the Gods: an Analysis of the Function of Yahweh in the Divine Council of Deuteronomy 32 and Psalm 82

LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY AND GRADUATE SCHOOL GOD AMONG THE GODS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE FUNCTION OF YAHWEH IN THE DIVINE COUNCIL OF DEUTERONOMY 32 AND PSALM 82 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF RELIGION IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES BY DANIEL PORTER LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA MAY 2010 The views expressed in this thesis do not necessarily represent the views of the institution and/or of the thesis readers. Copyright © 2010 by Daniel Porter All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my wife, Mariel And My Parents, The Rev. Fred A. Porter and Drenda Porter Special thanks to Dr. Ed Hindson and Dr. Al Fuhr for their direction and advice through the course of this project. iii ABSTRACT The importance of the Ugaritic texts discovered in 1929 to ancient Near Eastern and Biblical Studies is one of constant debate. The Ugaritic texts offer a window into the cosmology that shaped the ancient Near East and Semitic religions. One of the profound concepts is the idea of a divine council and its function in maintaining order in the cosmos. Over this council sits a high god identified as El in the Ugaritic texts whose divine function is to maintain order in the divine realm as well on earth. Due to Ugarit‟s involvement in the ancient world and the text‟s representation of Canaanite cosmology, scholars have argued that the Ugaritic pantheon is evidenced in the Hebrew Bible where Yahweh appears in conjunction with other divine beings. Drawing on imagery from both the Ugaritic and Hebrew texts, scholars argue that Yahweh was not originally the high god of Israel, and the idea of “Yahweh alone” was a progression throughout the biblical record. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

A Philosophical Investigation of the Nature of God in Igbo Ontology

Open Journal of Philosophy, 2015, 5, 137-151 Published Online March 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2015.52016 A Philosophical Investigation of the Nature of God in Igbo Ontology Celestine Chukwuemeka Mbaegbu Department of Philosophy, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Received 25 February 2015; accepted 3 March 2015; published 4 March 2015 Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract In its general task, philosophy as an academic or professional exercise is a conscious, critical, per- sonal reflection on human experience, on man, and how he perceives and interprets his world. This article specifically examines the nature of God in Igbo ontology. It is widely accepted by all philosophers that man in all cultures has the ability to philosophize. This was what Plato and Aris- totle would want us to believe, but it is not the same as saying that man has always philosophized in the academic meaning of the word in the sense of a coherent, systematic inquiry, since power and its use are different things altogether. Using the method of analysis and hermeneutics this ar- ticle sets out to discover, find out the inherent difficulties in the common sense views, ideas and insights of the pre-modern Igbo of Nigeria to redefine, refine and remodel them. The reason is sim- ple: Their concepts and nature of realities especially that of the nature of God were very hazy, in- articulate and confusing. -

10. Why Didn't Jesus Use the Septuagint?

10 Q Did Jesus and the apostles, including Paul, quote from the Septuagint? A There are absolutely no manuscripts pre-dating the third century A.D. to validate the claim that Jesus or Paul quoted a Greek Old Testament. Quotations by Jesus and Paul in new versions’ New Testaments may match readings in the so-called Septuagint because new versions are from the exact same corrupt fourth and fifth century A.D. manuscripts which underlie the document sold today and called the Septuagint. These manuscripts are Alexandrinus, Vaticanus, and Sinaiticus. According to the colophon on the end of Sinaiticus, it came from Origen’s Hexapla. The others likely did also. Even church historians, Jerome, Hort, and our contemporary D.A. Carson, would agree that this is probably true. Origen wrote his Hexapla two hundred years after the life of Christ and Paul! NIV New Testament and Old Testament quotes may match occasionally because they were both penned by the same hand — a hand which recast both Old and New Testament to suit his Platonic and Gnostic leanings. New versions take the Sinaiticus, Vaticanus, and Alexandrinus manuscripts — which are in fact Origen’s Hexapla — and change the traditional Masoretic Old Testament text to match these. Alfred Martin, who was a past vice- president of Moody Bible Institute, called Origen “unsafe.” Origen’s Hexapla is a very unsafe source to use to change the historic Old Testament. The preface of the Septuagint marketed today points out that the stories surrounding the B.C. (before Christ) creation of the Septuagint (LXX) and the existence of a Greek Old Testament are based on fables. -

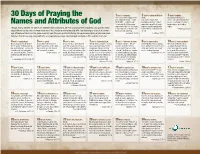

30 Days of Praying the Names and Attributes Of

30 Days of Praying the 1 God is Jehovah. 2 God is Jehovah-M’Kad- 3 God is infinite. The name of the independent, desh. God is beyond measure- self-complete being—“I AM This name means “the ment—we cannot define Him WHO I AM”—only belongs God who sanctifies.” A God by size or amount. He has no Names and Attributes of God to Jehovah God. Our proper separate from all that is evil beginning, no end, and no response to Him is to fall down requires that the people who limits. Though God is infinitely far above our ability to fully understand, He tells us through the Scriptures very specific truths in fear and awe of the One who follow Him be cleansed from —Romans 11:33 about Himself so that we can know what He is like, and be drawn to worship Him. The following is a list of 30 names possesses all authority. all evil. and attributes of God. Use this guide to enrich your time set apart with God by taking one description of Him and medi- —Exodus 3:13-15 —Leviticus 20:7,8 tating on that for one day, along with the accompanying passage. Worship God, focusing on Him and His character. 4 God is omnipotent. 5 God is good. 6 God is love. 7 God is Jehovah-jireh. 8 God is Jehovah-shalom. 9 God is immutable. 10 God is transcendent. This means God is all-power- God is the embodiment of God’s love is so great that He “The God who provides.” Just as “The God of peace.” We are All that God is, He has always We must not think of God ful. -

Elohim and Jehovah in Mormonism and the Bible

Elohim and Jehovah in Mormonism and the Bible Boyd Kirkland urrently, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints defines the CGodhead as consisting of three separate and distinct personages or Gods: Elohim, or God the Father; Jehovah, or Jesus Christ, the Son of God both in the spirit and in the flesh; and the Holy Ghost. The Father and the Son have physical, resurrected bodies of flesh and bone, but the Holy Ghost is a spirit personage. Jesus' title of Jehovah reflects his pre-existent role as God of the Old Testament. These definitions took official form in "The Father and the Son: A Doctrinal Exposition by the First Presidency and the Twelve" (1916) as the culmination of five major stages of theological development in Church history (Kirkland 1984): 1. Joseph Smith, Mormonism's founder, originally spoke and wrote about God in terms practically indistinguishable from then-current protestant the- ology. He used the roles, personalities, and titles of the Father and the Son interchangeably in a manner implying that he believed in only one God who manifested himself as three persons. The Book of Mormon, revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants prior to 1835, and Smith's 1832 account of his First Vision all reflect "trinitarian" perceptions. He did not use the title Elohim at all in this early stage and used Jehovah only rarely as the name of the "one" God. 2. The 1835 Lectures on Faith and Smith's official 1838 account of his First Vision both emphasized the complete separateness of the Father and the Son.