06 4 1979.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Greek Body in Crisis: Contemporary Dance as a Site of Negotiating and Restructuring National Identity in the Era of Precarity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0vg4w163 Author Zervou, Natalie Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Greek Body in Crisis: Contemporary Dance as a Site of Negotiating and Restructuring National Identity in the Era of Precarity A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Natalie Zervou June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Marta Elena Savigliano, Chairperson Dr. Linda J. Tomko Dr. Anthea Kraut Copyright Natalie Zervou 2015 The Dissertation of Natalie Zervou is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments This dissertation is the result of four years of intensive research, even though I have been engaging with this topic and the questions discussed here long before that. Having been born in Greece, and having lived there till my early twenties, it is the place that holds all my childhood memories, my first encounters with dance, my friends, and my family. From a very early age I remember how I always used to say that I wanted to study dance and then move to the US to pursue my dream. Back then I was not sure what that dream was, other than leaving Greece, where I often felt like I did not belong. Being here now, in the US, I think I found it and I must admit that when I first begun my pursuit in graduate studies in dance, I was very hesitant to engage in research concerning Greece. -

Annual Sustainability Report 2015

Annual Sustainability Report 2015 1 Message from Theano Metaxa, the Wife of the Founder Nikolaos Metaxas CRETA MARIS Ἒργο ζωῆς 40 χρόνων A 40 years work.. a life achievement The number 40 sacred symbol in Cretan folklore and the Christian religion. 40 days after the birth of the child the mother takes the wish. 40 days after death, is the memorial to the dead. 40 days is the Fast lasting before Christmas Eve. 40 days before the New Year Eve Christians bring the sacred icon to the church. 40 herbs and greens cooked for treatment. 40dentri (sarantadendri is a local plant) ... to dissolve the spell. 40 Saints (celebrating on March 2nd) “Forty sow, forty planted, forty reap.” (local saying) 40 waves should have passed the girls the silkworm eggs, in order to open. 40 years was the age of adulthood. Sarantari (Saranta means 40 in Greek) (location name) Sarantatris (family name) Sarantizo (greetings treat the evil eye) Centipede (in Greek called 40-legs) Number 40 is also used in many songs and Greek sayings. 40 – a very important number for our people, a very important number for Creta Maris. Forty years - a lifetime – of supply in Tourism, Crete, People. Let’s make them a hundred! 2 Message from the CEO, Andreas Metaxas “The amount of resources someone has is of minor importance in comparison with his willingness and expertise to implement these resources” The literal meaning of the word “Sustainability” in Greek is associated with the concept of bearing fruit eternally (“Αειφορία < αεί + -φορία”). In familiar lan- guage, sustainability means to produce/use a resource while maintaining the balance that exists in nature. -

A Primeira Guerra Mundial E Outros Ensaios

14 2014/1520152017 A PRIMEIRA GUERRA MUNDIAL E OUTROS ENSAIOS RESPUBLICA Revista de Ciência Política, Segurança e Relações Internacionais FICHA TÉCNICA Órgão do CICPRIS – Centro de Inves- Conselho Editorial tigação em Ciência Política, Relações Internacionais e Segurança (ULHT e ULP) Adelino Torres (Professor Emérito do ISEG) Adriano Moreira (Professor Emérito da Universidade Diretor de Lisboa) João de Almeida Santos Alberto Pena Subdiretor (Universidade de Vigo) José Filipe Pinto António Bento (Universidade da Beira Interior) Coordenador Editorial Sérgio Vieira da Silva António Fidalgo (Universidade da Beira Interior) Assessoras da Direção Enrique Bustamante Teresa Candeias (Universidade Complutense Elisabete Pinto da Costa de Madrid) Gianluca Passarelli Conselho de Redação (Universidade de Roma “La Sapienza”) Diogo Pires Aurélio, Elisabete Costa, Fer- nanda Neutel, Fernando Campos, João de Guilherme d’Oliveira Martins Almeida Santos, José Filipe Pinto, Manuel (Administrador da Fundação Calouste Gonçalves Martins, Paulo Mendes Pinto e Gulbenkian) Sérgio Vieira da Silva Javier Roca García (Universidade Complutense Colaboradores Permanentes de Madrid) Todos os membros do CICPRIS Jesús Timoteo Álvarez (Universidade Complutense de Madrid) João Cardoso Rosas Paulo Ferreira da Cunha (Universidade do Minho) (Universidade do Porto) John Loughlin Pierre Musso (Universidade de Cambridge) (Universidade de Rennes 2) José Bragança de Miranda Rafael Calduch (Universidade Nova de Lisboa e ULHT) (Universidade Complutense José Lamego de Madrid) (Universidade -

Albanian Families' History and Heritage Making at the Crossroads of New

Voicing the stories of the excluded: Albanian families’ history and heritage making at the crossroads of new and old homes Eleni Vomvyla UCL Institute of Archaeology Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor in Philosophy in Cultural Heritage 2013 Declaration of originality I, Eleni Vomvyla confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature 2 To the five Albanian families for opening their homes and sharing their stories with me. 3 Abstract My research explores the dialectical relationship between identity and the conceptualisation/creation of history and heritage in migration by studying a socially excluded group in Greece, that of Albanian families. Even though the Albanian community has more than twenty years of presence in the country, its stories, often invested with otherness, remain hidden in the Greek ‘mono-cultural’ landscape. In opposition to these stigmatising discourses, my study draws on movements democratising the past and calling for engagements from below by endorsing the socially constructed nature of identity and the denationalisation of memory. A nine-month fieldwork with five Albanian families took place in their domestic and neighbourhood settings in the areas of Athens and Piraeus. Based on critical ethnography, data collection was derived from participant observation, conversational interviews and participatory techniques. From an individual and family group point of view the notion of habitus led to diverse conceptions of ethnic identity, taking transnational dimensions in families’ literal and metaphorical back- and-forth movements between Greece and Albania. -

Modern Greek:Layout 1.Qxd

Modern Greek:Layout 1 10/11/2010 5:24 PM Page 1 MODERN GREEK STUDIES (AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND) Volume 14, 2010 A Journal for Greek Letters Pages on the Crisis of Representation: Nostalgia for Being Otherwise Modern Greek:Layout 1 10/11/2010 5:24 PM Page 4 CONTENTS SECTION ONE Joy Damousi Ethnicity and Emotions: Psychic Life in Greek Communities 17 Gail Holst-Warhaft National Steps: Can You Be Greek If You Can’t Dance a Zebekiko? 26 Despina Michael Μαύρη Γάτα: The Tragic Death and Long After-life of Anestis Delias 44 Shé M. Hawke The Ship Goes Both Ways: Cross-cultural Writing by Joy Damousi, Antigone Kefala, Eleni Nickas and Beverley Farmer 75 Peter Morgan The Wrong Side of History: Albania’s Greco-Illyrian Heritage in Ismail Kadare’s Aeschylus or the Great Loser 92 SECTION TWO Anthony Dracopoulos The Poetics of Analogy: On Polysemy in Cavafy’s Early Poetry 113 Panayota Nazou Weddings by Proxy: A Cross-cultural Study of the Proxy-Wedding Phenomenon in Three Films 127 Michael Tsianikas Τρεμολογια /Tremology 144 SECTION THREE Christos A. Terezis Aspects of Proclus’ Interpretation on the Theory of the Platonic Forms 170 Drasko Mitrikeski Nàgàrjuna’s Stutyatãtastava and Catuþstava: Questions of Authenticity 181 Modern Greek:Layout 1 10/11/2010 5:24 PM Page 5 CONTENTS 5 Vassilis Adrahtas and Paraskevi Triantafyllopoulou Religion and National/Ethnic Identity in Modern Greek Society: A Study of Syncretism 195 David Close Divided Attitudes to Gypsies in Greece 207 Bronwyn Winter Women and the ‘Turkish Paradox’: What The Headscarf is Covering Up -

The Greek Enlightenment and the Changing Cultural Status of Women

SOPHIA DENISSI The Greek Enlightenment and the Changing Cultural Status of Women In 1856 Andreas Laskaratos, one of the most liberal authors of his time, writes: There is no doubt that we took a giant step in allowing our women learning. This step reveals that a revolution took place in the spirit; a revolution which has taken our minds away from the road of backwardness and has led them to the road of progress. Though this transmission has not received any attention yet, it constitutes one of these events that will leave its trace in the history of the human spirit.1 Laskaratos is quite correct in talking about a revolution since the decision to accept women's education at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries was indeed a revolutionary act if we consider the state of Greek women who had been living in absolute ignorance and seclusion that prevailed throughout the years of the Ottoman occupation. What caused this revolution? What made Greek men, or rather a progressive minority at first, still subjects of the Ottoman Empire concede the right to education and even to a public voice for women? The answer will be revealed to us by taking a close look at the first educated Greek women who managed to break the traditional silence imposed upon their sex by patriarchal culture and make their presence felt in the male world. We can distinguish two main groups among the first educated Greek women; those coming from the aristocratic circle of the Phanariots and those coming from the circle of progressive men of letters. -

Theorising Return Migration

ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES Tolerance and Cultural Diversity Discourses in Greece Anna Triandafyllidou, Ifigeneia Kokkali European University Institute 2010/08 1. Overview National Discourses Background Country Reports EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES Tolerance and Cultural Diversity Discourses in Greece ANNA TRIANDAFYLLIDOU AND IFIGENEIA KOKKALI EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES Work Package 1 – Overview of National Discourses on Tolerance and Cultural Diversity D1.1 Country Reports on Tolerance and Cultural Diversity Discourses © 2010 Anna Triandafyllidou and Ifigeneia Kokkali This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the research project, the year and the publisher. Published by the European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Via dei Roccettini 9 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole - Italy ACCEPT PLURALISM Research Project, Tolerance, Pluralism and Social Cohesion: Responding to the Challenges of the 21st Century in Europe European Commission, DG Research Seventh Framework Programme Social Sciences and Humanities grant agreement no. 243837 www.accept-pluralism.eu www.eui.eu/RSCAS/ Available from the EUI institutional repository CADMUS cadmus.eui.eu Tolerance, Pluralism and Social Cohesion: Responding to the Challenges of the 21st Century in Europe (ACCEPT PLURALISM) ACCEPT PLURALISM is a Research Project, funded by the European Commission under the Seventh Framework Program. The project investigates whether European societies have become more or less tolerant during the past 20 years. -

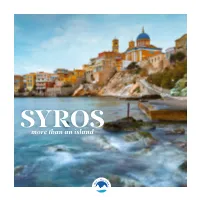

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

200Th Anniversary of the Greek War of Independence 1821-2021 18 1821-2021

Special Edition: 200th Anniversary of the Greek War of Independence 1821-2021 18 1821-2021 A publication of the Dean C. and Zoë S. Pappas Interdisciplinary March 2021 VOLUME 1 ISSUE NO. 3 Center for Hellenic Studies and the Friends of Hellenic Studies From the Director Dear Friends, On March 25, 1821, in the city of Kalamata in the southern Peloponnesos, the chieftains from the region of Mani convened the Messinian Senate of Kalamata to issue a revolutionary proclamation for “Liberty.” The commander Petrobey Mavromichalis then wrote the following appeal to the Americans: “Citizens of the United States of America!…Having formed the resolution to live or die for freedom, we are drawn toward you by a just sympathy; since it is in your land that Liberty has fixed her abode, and by you that she is prized as by our fathers.” He added, “It is for you, citizens of America, to crown this glory, in aiding us to purge Greece from the barbarians, who for four hundred years have polluted the soil.” The Greek revolutionaries understood themselves as part of a universal struggle for freedom. It is this universal struggle for freedom that the Pappas Center for Hellenic Studies and Stockton University raises up and celebrates on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the beginning of the Greek Revolution in 1821. The Pappas Center IN THIS ISSUE for Hellenic Studies and the Friends of Hellenic Studies have prepared this Special Edition of the Hellenic Voice for you to enjoy. In this Special Edition, we feature the Pappas Center exhibition, The Greek Pg. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

2011 Joint Conference

Joint ConferenceConference:: Hellenic Observatory,The British SchoolLondon at School Athens of & Economics & British School at Athens Hellenic Observatory, London School of Economics Changing Conceptions of “Europe” in Modern Greece: Identities, Meanings, and Legitimation 28 & 29 January 2011 British School at Athens, Upper House, entrance from 52 Souedias, 10676, Athens PROGRAMME Friday, 28 th January 2011 9:00 Registration & Coffee 9:30 Welcome : Professor Catherine Morgan , Director, British School at Athens 9:45 Introduction : Imagining ‘Europe’. Professor Kevin Featherstone , LSE 10:15 Session One : Greece and Europe – Progress and Civilisation, 1890s-1920s. Sir Michael Llewellyn-Smith 11:15 Coffee Break 11:30 Session Two : Versions of Europe in the Greek literary imagination (1929- 1961). Professor Roderick Beaton , King’s College London 12:30 Lunch Break 13:30 Session Three : 'Europe', 'Turkey' and Greek self-identity: The antinomies of ‘mutual perceptions'. Professor Stefanos Pesmazoglou , Panteion University Athens 14:30 Coffee Break 14:45 Session Four : The European Union and the Political Economy of the Greek State. Professor Georgios Pagoulatos , Athens University of Economics & Business 15:45 Coffee Break 16:00 Session Five : Contesting Greek Exceptionalism: the political economy of the current crisis. Professor Euclid Tsakalotos , Athens University Of Economics & Business 17:00 Close 19:00 Lecture : British Ambassador’s Residence, 2 Loukianou, 10675, Athens Former Prime Minister Costas Simitis on ‘European challenges in a time of crisis’ with a comment by Professor Kevin Featherstone 20:30 Reception 21:00 Private Dinner: British Ambassador’s Residence, 2 Loukianou, 10675, Athens - By Invitation Only - Saturday, 29 th January 2011 10:00 Session Six : Time and Modernity: Changing Greek Perceptions of Personal Identity in the Context of Europe.