Evdokia's Zeibekiko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dionysiac and Pyrrhic Roots and Survivals in the Zeybek Dance, Music, Costume and Rituals of Aegean Turkey

GEPHYRA 14, 2017, 213-239 Dionysiac and Pyrrhic Roots and Survivals in the Zeybek Dance, Music, Costume and Rituals of Aegean Turkey Recep MERİÇ In Memory of my Teacher in Epigraphy and the History of Asia Minor Reinhold Merkelbach Zeybek is a particular name in Aegean Turkey for both a type of dance music and a group of com- panions performing it wearing a particular decorative costume and with a typical headdress (Fig. 1). The term Zeybek also designates a man who is brave, a tough and courageous man. Zeybeks are gen- erally considered to be irregular military gangs or bands with a hierarchic order. A Zeybek band has a leader called efe; the inexperienced young men were called kızans. The term efe is presumably the survivor of the Greek word ephebos. Usually Zeybek is preceded by a word which points to a special type of this dance or the place, where it is performed, e.g. Aydın Zeybeği, Abdal Zeybeği. Both the appellation and the dance itself are also known in Greece, where they were called Zeibekiko and Abdaliko. They were brought to Athens after 1922 by Anatolian Greek refugees1. Below I would like to explain and attempt to show, whether the Zeybek dances in the Aegean provinces of western Turkey have any possible links with Dionysiac and Pyrrhic dances, which were very popular in ancient Anatolia2. Social status and origin of Zeybek Recently E. Uyanık3 and A. Özçelik defined Zeybeks in a quite appropriate way: “The banditry activ- ities of Zeybeks did not have any certain political aim, any systematic ideology or any organized re- ligious sect beliefs. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

SYRTAKI Greek PRONUNCIATION

SYRTAKI Greek PRONUNCIATION: seer-TAH-kee TRANSLATION: Little dragging dance SOURCE: Dick Oakes learned this dance in the Greek community of Los Angeles. Athan Karras, a prominent Greek dance researcher, also has taught Syrtaki to folk dancers in the United States, as have many other teachers of Greek dance. BACKGROUND: The Syrtaki, or Sirtaki, was the name given to the combination of various Hasapika (or Hassapika) dances, both in style and the variation of tempo, after its popularization in the motion picture Alexis Zorbas (titled Zorba the Greek in America). The Syrtaki is danced mainly in the taverns of Greece with dances such as the Zeybekiko (Zeimbekiko), the Tsiftetelli, and the Karsilamas. It is a combination of either a slow hasapiko and fast hasapiko, or a slow hasapiko, hasaposerviko, and fast hasapiko. It is typical for the musicians to "wake things up" after a slow or heavy (vari or argo) hasapiko with a medium and / or fast Hasapiko. The name "Syrtaki" is a misnomer in that it is derived from the most common Greek dance "Syrtos" and this name is a recent invention. These "butcher dances" spread throughout the Balkans and the Near East and all across the Aegean islands, and entertained a great popularity. The origins of the dance are traced to Byzantium, but the Argo Hasapiko is an evolved idiom by Aegean fisherman and their languid lifestyle. The name "Syrtaki" is now embedded as a dance form (meaning "little Syrtos," though it is totally unlike any Syrto dance), but its international fame has made it a hallmark of Greek dancing. -

Čarobnost Zvoka in Zavesti

EDUN EDUN SLOVANSKO-PITAGOREJSKA ANSAMBEL ZA STARO MEDITATIVNO KATEDRA ZA RAZVOJ ZAVESTI GLASBO IN OŽIVLJANJE SPIRITUALNIH IN HARMONIZIRANJE Z ZVOKOM ZDRAVILNIH ZVOKOV KULTUR SVETA ČAROBNOST ZVOKA IN ZAVESTI na predavanjih, tečajih in v knjigah dr. Mire Omerzel - Mirit in koncertno-zvočnih terapijah ansambla Vedun 1 I. NAŠA RESNIČNOST JE ZVOK Snovni in nesnovni svet sestavlja frekvenčno valovanje – slišno in neslišno. Toda naša danost, tudi zvenska, je mnogo, mnogo več. Zvok je alkimija frekvenc in njihovih energij, orodje za urejanje in zdravljenje subtilnih teles duha in fizičnega telesa ter orodje za širjenje zavesti in izostrovanje čutil in nadčutil. Z zvokom (resonanco) se lahko sestavimo v harmonično celoto in uglasimo z naravnimi ritmi, zaradi razglašenosti (disonance) pa lahko zbolimo. Modrosti svetovnih glasbenih tradicij povezujejo človekovo zavest z nezavednim in nadzavednim ter z zvočnimi vzorci brezmejnega, brezčasnega in večnega. Zvok nas povezuje z Velikim Snovnim Slušnim Logosom Univerzuma in Kozmično Inteligenco življenja oziroma Zavestjo Narave, ki jo vse bolj odkrivata tudi subatomska fizika in medicina. Zvok je ključ tistih vrat »duše in srca«, ki odpirajo subtilne svetove »onkraj« običajne zavesti, v mnogodimenzionalne svetove resničnosti in zavesti ter v transcendentalne svetove. Knjige dr. Mire Omerzel - Mirit, še zlasti knjižna serija Kozmična telepatija, njene delavnice in tečaji, pa tudi koncerti in zgoščenke njenega ansambla Vedun (glasbenikov – zvočnih terapevtov – medijev, ki muzicirajo v transcendentalnem stanju zavesti), vodijo bralce in poslušalce na najgloblje ravni duše, v zvočno prvobitnost, k Viru življenja, v središče in pravljične svetove človekovega duha. Zvoku Mirit in glasbeni sodelavci z besedo, glasbo in zvočno »kirurgijo« vračajo urejajočo in zdravilno moč, nekdanjo svečeniško noto in svetost. -

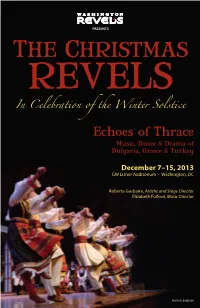

Read This Year's Christmas Revels Program Notes

PRESENTS THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey December 7–15, 2013 GW Lisner Auditorium • Washington, DC Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director PHOTO BY ROGER IDE THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey The Washington Featuring Revels Company Karpouzi Trio Koleda Chorus Lyuti Chushki Koros Teens Spyros Koliavasilis Survakari Children Tanya Dosseva & Lyuben Dossev Thracian Bells Tzvety Dosseva Weiner Grum Drums Bryndyn Weiner Kukeri Mummers and Christmas Kamila Morgan Duncan, as The Poet With And Folk-Dance Ensembles The Balkan Brass Byzantio (Greek) and Zharava (Bulgarian) Emerson Hawley, tuba Radouane Halihal, percussion Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director Gregory C. Magee, Production Manager Dedication On September 1, 2013, Washington Revels lost our beloved Reveler and friend, Kathleen Marie McGhee—known to everyone in Revels as Kate—to metastatic breast cancer. Office manager/costume designer/costume shop manager/desktop publisher: as just this partial list of her roles with Revels suggests, Kate was a woman of many talents. The most visibly evident to the Revels community were her tremendous costume skills: in addition to serving as Associate Costume Designer for nine Christmas Revels productions (including this one), Kate was the sole costume designer for four of our five performing ensembles, including nineteenth- century sailors and canal folk, enslaved and free African Americans during Civil War times, merchants, society ladies, and even Abraham Lincoln. Kate’s greatest talent not on regular display at Revels related to music. -

Modern Greek:Layout 1.Qxd

Modern Greek:Layout 1 10/11/2010 5:24 PM Page 1 MODERN GREEK STUDIES (AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND) Volume 14, 2010 A Journal for Greek Letters Pages on the Crisis of Representation: Nostalgia for Being Otherwise Modern Greek:Layout 1 10/11/2010 5:24 PM Page 4 CONTENTS SECTION ONE Joy Damousi Ethnicity and Emotions: Psychic Life in Greek Communities 17 Gail Holst-Warhaft National Steps: Can You Be Greek If You Can’t Dance a Zebekiko? 26 Despina Michael Μαύρη Γάτα: The Tragic Death and Long After-life of Anestis Delias 44 Shé M. Hawke The Ship Goes Both Ways: Cross-cultural Writing by Joy Damousi, Antigone Kefala, Eleni Nickas and Beverley Farmer 75 Peter Morgan The Wrong Side of History: Albania’s Greco-Illyrian Heritage in Ismail Kadare’s Aeschylus or the Great Loser 92 SECTION TWO Anthony Dracopoulos The Poetics of Analogy: On Polysemy in Cavafy’s Early Poetry 113 Panayota Nazou Weddings by Proxy: A Cross-cultural Study of the Proxy-Wedding Phenomenon in Three Films 127 Michael Tsianikas Τρεμολογια /Tremology 144 SECTION THREE Christos A. Terezis Aspects of Proclus’ Interpretation on the Theory of the Platonic Forms 170 Drasko Mitrikeski Nàgàrjuna’s Stutyatãtastava and Catuþstava: Questions of Authenticity 181 Modern Greek:Layout 1 10/11/2010 5:24 PM Page 5 CONTENTS 5 Vassilis Adrahtas and Paraskevi Triantafyllopoulou Religion and National/Ethnic Identity in Modern Greek Society: A Study of Syncretism 195 David Close Divided Attitudes to Gypsies in Greece 207 Bronwyn Winter Women and the ‘Turkish Paradox’: What The Headscarf is Covering Up -

Music, Image, and Identity: Rebetiko and Greek National Identity

Universiteit van Amsterdam Graduate School for Humanities Music, Image, and Identity: Rebetiko and Greek National Identity Alexia Kallergi Panopoulou Student number: 11655631 MA Thesis in European Studies, Identity and Integration track Name of supervisor: Dr. Krisztina Lajosi-Moore Name of second reader: Prof. dr. Joep Leerssen September 2018 2 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1 .............................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Theory and Methodology ........................................................................................................ 6 Chapter 2. ........................................................................................................................... 11 2.1 The history of Rebetiko ......................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Kleftiko songs: Klephts and Armatoloi ............................................................................... 11 2.1.2 The Period of the Klephts Song .......................................................................................... 15 2.2 Rebetiko Songs...................................................................................................................... 18 2.3 Rebetiko periods .................................................................................................................. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/25/2021 04:09:39AM Via Free Access 96 Yagou

Please provide footnote text CHAPTER 4 A Dialogue of Sources: Greek Bourgeois Women and Material Culture in the Long 18th Century Artemis Yagou The Context In the Ottoman-dominated Europe of the Early Modern period (17th to 19th centuries), certain non-Muslim populations, especially the Christian elites, defined their social status and identity at the intersection of East and West. The westernization of southeastern Europe proceeded not just through the spread of Enlightenment ideas and the influence of the French Revolution, but also through changes in visual culture brought about by western influence on notions of luxury and fashion. This approach allows a closer appreciation of the interactions between traditional culture, political thought, and social change in the context of the modernization or “Europeanization” of this part of Europe.1 The role of the “conquering Balkan Orthodox merchant” in these processes has been duly emphasized.2 The Balkan Orthodox merchant represented the main vehicle of interaction and interpenetration between the Ottoman realm and the West, bringing the Balkans closer to Europe than ever before.3 The gradual expansion of Greek merchants beyond local trade and their penetra- tion into export markets is the most characteristic event of the 18th century in Ottoman-dominated Greece.4 This was triggered by political developments, more specifically the treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774, the opening of the Black 1 LuxFaSS Research Project, http://luxfass.nec.ro, [accessed 30 May 2017]. 2 Troian Stoianovich. “The Conquering Balkan Orthodox Merchant,” The Journal of Economic History 20 (1960): 234–313. 3 Fatma Müge Göçek, East Encounters West: France and the Ottoman Empire in the Eighteenth Century (New York, 1987); Vladislav Lilić, “The Conquering Balkan Orthodox Merchant, by Traian Stoianovich. -

Rhythmo-Melodic Patterns of Modi Performed on the Santouri by Nikos Kalaitzis by Mema Papandrikou

IMS-RASMB, Series Musicologica Balcanica 1.1, 2020. e-ISSN: 2654-248X Rhythmo-Melodic Patterns of Modi Performed on the Santouri by Nikos Kalaitzis by Mema Papandrikou DOI: https://doi.org/10.26262/smb.v1i1.7751 ©2020 The Author. This is an open access article under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercialNoDerivatives International 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/ (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the articles is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made. Papandrikou, Rhythmo-Melodic Patterns… Rhythmo-Melodic Patterns of Modi Performed on the Santouri by Nikos Kalaitzis Mema Papandrikou Abstract: Greek folk music follows the non-tempered modal musical system of the Byzantine ochtoechos. The Greek santouri is a music instrument tuned chromatically after the well-tempered system. As there is no ability of performing microtones, all modes are played on the well-tempered scale. Nikos Kalaitzis or “Bidagialas”, one of the greatest Greek santouri players, uses his excellent skill in order to perform folk music as close to the non-tempered modal system as possible. He focuses on the basic features of each mode/echos and tries to express the style of each one using various melodic and rhythmic techniques. Through the study of two characteristic dance tunes in different modes from the island of Lesbos, we see analytically the rhythmo-melodic patterns which are used on the santouri by this great musician and help to determine the identification of modes. -

Greek Cultures, Traditions and People

GREEK CULTURES, TRADITIONS AND PEOPLE Paschalis Nikolaou – Fulbright Fellow Greece ◦ What is ‘culture’? “Culture is the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, encompassing language, religion, cuisine, social habits, music and arts […] The word "culture" derives from a French term, which in turn derives from the Latin "colere," which means to tend to the earth and Some grow, or cultivation and nurture. […] The term "Western culture" has come to define the culture of European countries as well as those that definitions have been heavily influenced by European immigration, such as the United States […] Western culture has its roots in the Classical Period of …when, to define, is to the Greco-Roman era and the rise of Christianity in the 14th century.” realise connections and significant overlap ◦ What do we mean by ‘tradition’? ◦ 1a: an inherited, established, or customary pattern of thought, action, or behavior (such as a religious practice or a social custom) ◦ b: a belief or story or a body of beliefs or stories relating to the past that are commonly accepted as historical though not verifiable … ◦ 2: the handing down of information, beliefs, and customs by word of mouth or by example from one generation to another without written instruction ◦ 3: cultural continuity in social attitudes, customs, and institutions ◦ 4: characteristic manner, method, or style in the best liberal tradition GREECE: ANCIENT AND MODERN What we consider ancient Greece was one of the main classical The Modern Greek State was founded in 1830, following the civilizations, making important contributions to philosophy, mathematics, revolutionary war against the Ottoman Turks, which started in astronomy, and medicine. -

Glossary Ahengu Shkodran Urban Genre/Repertoire from Shkodër

GLOSSARY Ahengu shkodran Urban genre/repertoire from Shkodër, Albania Aksak ‘Limping’ asymmetrical rhythm (in Ottoman theory, specifically 2+2+2+3) Amanedes Greek-language ‘oriental’ urban genre/repertory Arabesk Turkish vocal genre with Arabic influences Ashiki songs Albanian songs of Ottoman provenance Baïdouska Dance and dance song from Thrace Čalgiya Urban ensemble/repertory from the eastern Balkans, especially Macedonia Cântarea României Romanian National Song Festival: ‘Singing for Romania’ Chalga Bulgarian ethno-pop genre Çifteli Plucked two-string instrument from Albania and Kosovo Čoček Dance and musical genre associated espe- cially with Balkan Roma Copla Sephardic popular song similar to, but not identical with, the Spanish genre of the same name Daouli Large double-headed drum Doina Romanian traditional genre, highly orna- mented and in free rhythm Dromos Greek term for mode/makam (literally, ‘road’) Duge pjesme ‘Long songs’ associated especially with South Slav traditional music Dvojka Serbian neo-folk genre Dvojnica Double flute found in the Balkans Echos A mode within the 8-mode system of Byzan- tine music theory Entekhno laïko tragoudhi Popular art song developed in Greece in the 1960s, combining popular musical idioms and sophisticated poetry Fanfara Brass ensemble from the Balkans Fasil Suite in Ottoman classical music Floyera Traditional shepherd’s flute Gaida Bagpipes from the Balkan region 670 glossary Ganga Type of traditional singing from the Dinaric Alps Gazel Traditional vocal genre from Turkey Gusle One-string, -

RCA Victor International FPM/FSP 100 Series

RCA Discography Part 26 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor International FPM/FSP 100 Series FPM/FSP 100 – Neapolitan Mandolins – Various Artists [1961] Torna A Surriento/Anema E Core/'A Tazza 'E Caffe/Funiculi Funicula/Voce 'E Notte/Santa Lucia/'Na Marzianina A Napule/'O Sole Mio/Oi Mari/Guaglione/Lazzarella/'O Mare Canta/Marechiaro/Tarantella D'o Pazzariello FPM/FSP 101 – Josephine Baker – Josephine Baker [1961] J'ai Deux Amours/Ca C'est Paris/Sur Les Quais Du Vieux Paris/Sous Les Ponts De Paris/La Seine/Mon Paris/C'est Paris/En Avril À Paris, April In Paris, Paris Tour Eiffel/Medley: Sous Les Toits De Paris, Sous Le Ciel De Paris, La Romance De Paris, Fleur De Paris FPM/FSP 102 – Los Chakachas – Los Chakachas [1961] Never on Sunday/Chocolate/Ca C’est Du Poulet/Venus/Chouchou/Negra Mi Cha Cha Cha/I Ikosara/Mucho Tequila/Ay Mulata/Guapacha/Pollo De Carlitos/Asi Va La Vida FPM/FSP 103 – Magic Violins of Villa Fontana – Magic Violins of Villa Fontana [1961] Reissue of LPM 1291. Un Del di Vedremo/Rubrica de Amor/Gigi/Alborada/Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1/Medley/Estrellita/Xochimilco/Adolorido/Carousel Waltz/June is Bustin’ Out All Over/If I Loved You/O Sole Mio/Santa Lucia/Tarantella FPM/FSP 104 – Ave a Go Wiv the Buskers – Buskers [1961] Glorious Beer/The Sunshine of Paradise Alley/She Told Me to Meet Her at the Gate/Nellie Dean/After the Ball/I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside//Any Old Iron/Down At the Old Bull and Bush/Boiled Beef and Carrots/The Sunshine of Your Smile/Wot Cher