2021Alkinsdmscres.Pdf with Marking the Unmarkable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khalladi-Bpp Anexes-Arabic.Pdf

Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 107 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 108 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 109 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 110 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 111 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 112 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 113 The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria are intended to be an easily and widely understood system for classifying species at high risk of global extinction. The IUCN Red List is categorized in the following Categories: • Extinct (EX): A taxon is Extinct when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form. Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects 114 Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 • Extinct in the Wild (EW): A taxon is Extinct in the Wild when it is known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity or as a naturalized population (or populations) well outside the past range. A taxon is presumed Extinct in the Wild when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. -

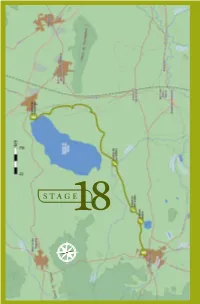

B I R D W a T C H I N G •

18 . F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS STAGE18 E S N O 158 BIRDWATCHING • GR-249 Great Path of Malaga F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS 18 . STAGE 18 Fuente de Piedra - Campillos L O C A T I O N he José Antonio Valverde Visitor´s Centre at the TReserva Natural de la Laguna de Fuente de Piedra is the starting point of Stage 18. Taking the direction south around the taken up mainly by olive trees and grain. eastern side of the salt water lagoon This type of environment will continue to you will be walking through farmland the end of this stage and it determines until the end of this stage in Campillos the species of birds which can be seen village. The 15, 7 km of Stage 18 will here. You will be crossing a stream and allow you to discover this wetland well then walking along the two lakes which known at national level in Spain, and will make your Stage 18 bird list fill cultivated farmland which creates a up with highly desirable species. The steppe-like environment. combination of wetland and steppe creates very valuable habitats with DESCRIPTION a rare composition of taxa unique at European level. ABOUT THE BIRDLIFE: Stage 18 begins at the northern tip HIGHLIGHTED SPECIES of the lagoon where you take direction Neither the length, diffi culty level or south through agricultural environment, elevation gain of this stage is particularly DID YOU KNOW? ecilio Garcia de la Leña, in Conversation 9th of “Historical Conversations of Malaga” published by Cristóbal Medina Conde (1726-1798) and entitled «About Animal Kingdom of Malaga and some Places in its Bishopric», Ccomments: «…In some lagoons, along sea shores and river banks some large and beautiful birds breed, called Flamingos and Phoenicopteros according to the ancients...», after a description of the bird´s anatomy he adds: «The Romans appreciated the bird greatly, especially its tongue which was served as an exquisite dish…». -

Tail Breakage and Predatory Pressure Upon Two Invasive Snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at Two Islands in the Western Mediterranean

Canadian Journal of Zoology Tail breakage and predatory pressure upon two invasive snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at two islands in the Western Mediterranean Journal: Canadian Journal of Zoology Manuscript ID cjz-2020-0261.R2 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 17-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Febrer-Serra, Maria; University of the Balearic Islands Lassnig, Nil; University of the Balearic Islands Colomar, Victor; Consorci per a la Recuperació de la Fauna de les Illes Balears Draft Sureda Gomila, Antoni; University of the Balearic Islands; Carlos III Health Institute, CIBEROBC Pinya Fernández, Samuel; University of the Balearic Islands, Biology Is your manuscript invited for consideration in a Special Not applicable (regular submission) Issue?: Zamenis scalaris, Hemorrhois hippocrepis, invasive snakes, predatory Keyword: pressure, Balearic Islands, frequency of tail breakage © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 34 Canadian Journal of Zoology 1 Tail breakage and predatory pressure upon two invasive snakes (Serpentes: 2 Colubridae) at two islands in the Western Mediterranean 3 4 M. Febrer-Serra, N. Lassnig, V. Colomar, A. Sureda, S. Pinya* 5 6 M. Febrer-Serra. Interdisciplinary Ecology Group. University of the Balearic Islands, 7 Ctra. Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain. E-mail address: 8 [email protected]. 9 N. Lassnig. Interdisciplinary Ecology Group. University of the Balearic Islands, Ctra. 10 Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain. E-mail address: 11 [email protected]. 12 V. Colomar. Consortium for the RecoveryDraft of Fauna of the Balearic Islands (COFIB). 13 Government of the Balearic Islands, Spain. -

Contents Herpetological Journal

British Herpetological Society Herpetological Journal Volume 31, Number 3, 2021 Contents Full papers Killing them softly: a review on snake translocation and an Australian case study 118-131 Jari Cornelis, Tom Parkin & Philip W. Bateman Potential distribution of the endemic Short-tailed ground agama Calotes minor (Hardwicke & Gray, 132-141 1827) in drylands of the Indian sub-continent Ashish Kumar Jangid, Gandla Chethan Kumar, Chandra Prakash Singh & Monika Böhm Repeated use of high risk nesting areas in the European whip snake, Hierophis viridiflavus 142-150 Xavier Bonnet, Jean-Marie Ballouard, Gopal Billy & Roger Meek The Herpetological Journal is published quarterly by Reproductive characteristics, diet composition and fat reserves of nose-horned vipers (Vipera 151-161 the British Herpetological Society and is issued free to ammodytes) members. Articles are listed in Current Awareness in Marko Anđelković, Sonja Nikolić & Ljiljana Tomović Biological Sciences, Current Contents, Science Citation Index and Zoological Record. Applications to purchase New evidence for distinctiveness of the island-endemic Príncipe giant tree frog (Arthroleptidae: 162-169 copies and/or for details of membership should be made Leptopelis palmatus) to the Hon. Secretary, British Herpetological Society, The Kyle E. Jaynes, Edward A. Myers, Robert C. Drewes & Rayna C. Bell Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK. Instructions to authors are printed inside the Description of the tadpole of Cruziohyla calcarifer (Boulenger, 1902) (Amphibia, Anura, 170-176 back cover. All contributions should be addressed to the Phyllomedusidae) Scientific Editor. Andrew R. Gray, Konstantin Taupp, Loic Denès, Franziska Elsner-Gearing & David Bewick A new species of Bent-toed gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Cyrtodactylus Gray, 1827) from the Garo 177-196 Hills, Meghalaya State, north-east India, and discussion of morphological variation for C. -

Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco: a Taxonomic Update and Standard Arabic Names

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 1-14 (2021) (published online on 08 January 2021) Checklist of amphibians and reptiles of Morocco: A taxonomic update and standard Arabic names Abdellah Bouazza1,*, El Hassan El Mouden2, and Abdeslam Rihane3,4 Abstract. Morocco has one of the highest levels of biodiversity and endemism in the Western Palaearctic, which is mainly attributable to the country’s complex topographic and climatic patterns that favoured allopatric speciation. Taxonomic studies of Moroccan amphibians and reptiles have increased noticeably during the last few decades, including the recognition of new species and the revision of other taxa. In this study, we provide a taxonomically updated checklist and notes on nomenclatural changes based on studies published before April 2020. The updated checklist includes 130 extant species (i.e., 14 amphibians and 116 reptiles, including six sea turtles), increasing considerably the number of species compared to previous recent assessments. Arabic names of the species are also provided as a response to the demands of many Moroccan naturalists. Keywords. North Africa, Morocco, Herpetofauna, Species list, Nomenclature Introduction mya) led to a major faunal exchange (e.g., Blain et al., 2013; Mendes et al., 2017) and the climatic events that Morocco has one of the most varied herpetofauna occurred since Miocene and during Plio-Pleistocene in the Western Palearctic and the highest diversities (i.e., shift from tropical to arid environments) promoted of endemism and European relict species among allopatric speciation (e.g., Escoriza et al., 2006; Salvi North African reptiles (Bons and Geniez, 1996; et al., 2018). Pleguezuelos et al., 2010; del Mármol et al., 2019). -

Long- and Short-Term Impact of Temperature on Snake Detection in the Wild: Further Evidence from the Snake Hemorrhois Hippocrepis

Acta Herpetologica 5(2): 143-150, 2010 Long- and short-term impact of temperature on snake detection in the wild: further evidence from the snake Hemorrhois hippocrepis Francisco J. Zamora-Camacho1,*, Gregorio Moreno-Rueda2, Juan M. Pleguezuelos1 1 Departamento de Biología Animal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Granada, E-18071, Grana- da, Spain. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Estación Experimental de Zonas Áridas (CSIC), La Cañada de San Urbano, Ctra. Sacramento s/n, E-04120, Almería, Spain. Submitted on: 2010, 25th February; revised on: 2010, 15th, August; accepted on: 2010, 22th, October. Abstract. Global change is causing an average temperature increment which affects several aspects of organisms’ biology, especially in ectotherms. Nevertheless, there is still scant knowledge about how this change is affecting reptiles. This paper shows that, the higher average temperature in a year, the more individuals of the snake Hem- orrhois hippocrepis are found in the field, because temperature increases the snakes’ activity. Furthermore, the quantity of snakes found was also correlated with the tem- perature of the previous years. Our results suggest that environmental temperature increases the population size of this species, which could benefit from the tempera- ture increment caused by climatic change. However, we did not find an increase in population size with the advance of years, suggesting that other factors have negatively impacted on this species, balancing the effect of increasing temperature. Keywords. -

Deliberate Tail Loss in Dolichophis Caspius and Natrix Tessellata (Serpentes: Colubridae) with a Brief Review of Pseudoautotomy in Contemporary Snake Families

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 12 (2): 367-372 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2016 Article No.: e162503 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Deliberate tail loss in Dolichophis caspius and Natrix tessellata (Serpentes: Colubridae) with a brief review of pseudoautotomy in contemporary snake families Jelka CRNOBRNJA-ISAILOVIĆ1,2,*, Jelena ĆOROVIĆ2 and Balint HALPERN3 1. Faculty of Sciences and Mathematics, University of Niš, Višegradska 33, 18000 Niš, Serbia. 2. Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, University of Belgrade, Despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia. 3. MME BirdLife Hungary, Költő u. 21, 1121 Budapest, Hungary. * Corresponding author, J. Crnobrnja-Isailović, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 22. April 2015 / Accepted: 16. July 2015 / Available online: 29. July 2015 / Printed: December 2016 Abstract. Deliberate tail loss was recorded for the first time in three large whip snakes (Dolichophis caspius) and one dice snake (Natrix tessellata). Observations were made in different years and in different locations. In all cases the tail breakage happened while snakes were being handled by researchers. Pseudoautotomy was confirmed in one large whip snake by an X-Ray photo of a broken piece of the tail, where intervertebral breakage was observed. This evidence and literature data suggest that many colubrid species share the ability for deliberate tail loss. However, without direct observation or experiment it is not possible to prove a species’ ability for pseudoautotomy, as a broken tail could also be evidence of an unsuccessful predator attack, resulting in a forcefully broken distal part of the tail. Key words: deliberate tail loss, pseudoautotomy, Colubridae, Dolichophis caspius, Natrix tessellate. -

Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of Risk Assessments: Final Report (Year 1) - Annex 4: Risk Assessment for Lampropeltis Getula

Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of Risk Assessments: Final Report (year 1) - Annex 4: Risk assessment for Lampropeltis getula Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of risk assessments to tackle priority species and enhance prevention Contract No 07.0202/2016/740982/ETU/ENV.D2 Final Report Annex 4: Risk Assessment for Lampropeltis getula (Linnaeus, 1766) November 2017 1 Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of Risk Assessments: Final Report (year 1) - Annex 4: Risk assessment for Lampropeltis getula Risk assessment template developed under the "Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of risk assessments to tackle priority species and enhance prevention" Contract No 07.0202/2016/740982/ETU/ENV.D2 Based on the Risk Assessment Scheme developed by the GB Non-Native Species Secretariat (GB Non-Native Risk Assessment - GBNNRA) Name of organism: Common kingsnake Lampropeltis getula (Linnaeus, 1766) Author(s) of the assessment: ● Yasmine Verzelen, Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Brussels, Belgium ● Tim Adriaens, Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Brussels, Belgium ● Riccardo Scalera, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group, Rome, Italy ● Niall Moore, GB Non-Native Species Secretariat, Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), York, Great Britain ● Wolfgang Rabitsch, Umweltbundesamt, Vienna, Austria ● Dan Chapman, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (CEH), Wallingford, Great Britain ● Peter Robertson, Newcastle University, Newcastle, Great Britain Risk Assessment Area: The geographical coverage of the risk assessment is the territory of the European Union (excluding the outermost regions) Peer review 1: Olaf Booy, GB Non-Native Species Secretariat, Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), York, Great Britain Peer review 2: Ramón Gallo Barneto, Área de Medio Ambiente e Infraestructuras. -

Patterns of Biological Invasion in the Herpetofauna of the Balearic Islands: Determining the Origin and Predicting the Expansion As Conservation Tools

Universidade do Porto Faculdade de Ciências Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos Patterns of biological invasion in the herpetofauna of the Balearic Islands: Determining the origin and predicting the expansion as conservation tools. Mestrado em Biodiversidade, Genética e Evolução Iolanda Raquel Silva Rocha May 2012 2 Iolanda Raquel Silva Rocha Patterns of biological invasion in the herpetofauna of the Balearic Islands: Determining the origin and predicting the expansion as conservation tools. Thesis submitted in order to obtain the Master’s degree in Biodiversity, Genetics and Evolution Supervisors: Dr. Miguel A. Carretero and Dr. Daniele Salvi CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos 3 4 Para ser grande, sê inteiro: nada Teu exagera ou exclui. Sê todo em cada coisa. Põe quanto és No mínimo que fazes. Assim em cada lago a lua toda Brilha, porque alta vive. 5 6 Acknowledgments Firstly, I want to say a couple of words about my choice. In the end of my Graduation, I was confused about what Masters I should attend. I chose this Masters on Biodiversity, Genetics and Evolution, due to the possibility of be in a research center of excellence and develope skills in genetics, since in graduation I did more ecological works. I knew that I did not want to do only genetics, then the group of Integrative Biogreography, Ecology and Evolution, attacted my attention. When this theme was proposed me, I felt really excited and I though ‘This is it! My perfect thesis theme’. Indeed, my decision of being in this Masters became more accurate, through the development of this work. -

A High Predation Rate by the Introduced Horseshoe Whip Snake Hemorrhois Hippocrepis Paints a Bleak Future for the Endemic Ibiza Wall Lizard Podarcis Pityusensis

Eur J Wildl Res (2017)63:13 DOI 10.1007/s10344-016-1068-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE The fall of a symbol? A high predation rate by the introduced horseshoe whip snake Hemorrhois hippocrepis paints a bleak future for the endemic Ibiza wall lizard Podarcis pityusensis Arlo Hinckley1 & Elba Montes2 & Enrique Ayllón3 & Juan M Pleguezuelos4 Received: 27 June 2016 /Revised: 28 August 2016 /Accepted: 30 November 2016 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2016 Abstract Invasive species currently account for a major threat the predation pressure on the endemic Podarcis pityusensis, to global biodiversity, and island ecosystems are among the the only native reptile in the island, is very high, as this lizard most vulnerable, because of the frequency and success of spe- represents 56% of the prey in frequency, which might threaten cies introductions on islands. Within Mediterranean islands, its survival on the long term. Our results on the feeding ecol- reptiles not only are frequently introduced species but are also ogy of the snake are of sufficient concern to justify the main- among the most threatened because of these introductions. The tenance of actions to eradicate this invader. Balearic archipelago is a good example of this, since only two of its current 16 species of reptiles are native. Thirteen years Keywords Balearic islands . Hemorrhois hippocrepis . ago, the snake Hemorrhois hippocrepis was introduced by Invasive species . Snake . Lizard cargo in Ibiza island, and it is in expansion. Individuals obtain- ed from an early eradication campaign showed a fast expres- sion of phenotypic plasticity and acquired larger sizes than Introduction those of the source population, probably due to a high prey availability and predator scarcity. -

Review Species List of the European Herpetofauna – 2020 Update by the Taxonomic Committee of the Societas Europaea Herpetologi

Amphibia-Reptilia 41 (2020): 139-189 brill.com/amre Review Species list of the European herpetofauna – 2020 update by the Taxonomic Committee of the Societas Europaea Herpetologica Jeroen Speybroeck1,∗, Wouter Beukema2, Christophe Dufresnes3, Uwe Fritz4, Daniel Jablonski5, Petros Lymberakis6, Iñigo Martínez-Solano7, Edoardo Razzetti8, Melita Vamberger4, Miguel Vences9, Judit Vörös10, Pierre-André Crochet11 Abstract. The last species list of the European herpetofauna was published by Speybroeck, Beukema and Crochet (2010). In the meantime, ongoing research led to numerous taxonomic changes, including the discovery of new species-level lineages as well as reclassifications at genus level, requiring significant changes to this list. As of 2019, a new Taxonomic Committee was established as an official entity within the European Herpetological Society, Societas Europaea Herpetologica (SEH). Twelve members from nine European countries reviewed, discussed and voted on recent taxonomic research on a case-by-case basis. Accepted changes led to critical compilation of a new species list, which is hereby presented and discussed. According to our list, 301 species (95 amphibians, 15 chelonians, including six species of sea turtles, and 191 squamates) occur within our expanded geographical definition of Europe. The list includes 14 non-native species (three amphibians, one chelonian, and ten squamates). Keywords: Amphibia, amphibians, Europe, reptiles, Reptilia, taxonomy, updated species list. Introduction 1 - Research Institute for Nature and Forest, Havenlaan 88 Speybroeck, Beukema and Crochet (2010) bus 73, 1000 Brussel, Belgium (SBC2010, hereafter) provided an annotated 2 - Wildlife Health Ghent, Department of Pathology, Bacteriology and Avian Diseases, Ghent University, species list for the European amphibians and Salisburylaan 133, 9820 Merelbeke, Belgium non-avian reptiles. -

Exploring Body Injuries in the Horseshoe Whip Snake, Hemorrhois Hippocrepis

Acta Herpetologica 13(1): 65-73, 2018 DOI: 10.13128/Acta_Herpetol-22465 Exploring body injuries in the horseshoe whip snake, Hemorrhois hippocrepis Juan M. Pleguezuelos*, Esmeralda Alaminos, Mónica Feriche Dep. Zoología, Fac. Ciencias, Univ. Granada, E-18071 Granada, Spain. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Submitted on: 2017, 18th September; revised on: 2017, 10th November; accepted on: 2018, 7th January Editor: Dario Ottonello Abstract. Body injuries on snakes may serve as indices of predation rate, which is otherwise difficult to record by direct methods because of the usual scarcity and shy nature of these reptiles. We studied the incidence of body scar- ring and tail breakage in a Mediterranean colubrid, Hemorrhois hippocrepis, from south-eastern Spain. This species exhibits two traits that favour tail breakage, a long tail and active foraging tactics. The large sample (n = 328) of indi- viduals acquired also enabled us to determine how the incidence of these injuries varies ontogenetically, between the sexes, in relation to energy stores, and to seek for the possible existence of multiple tail breakage. Overall, the inci- dence of tail breakage was rather low (13.1%) and similar to that of body scarring (12.7%). However, there was a sig- nificant ontogenetic shift in the incidence of tail breakage; such injuries barely appeared in immature snakes but stub- tailed individuals were present in 38.7% of snakes in the upper decile of body size. In contrast to most other studies, our data show a sex difference in the incidence of these injuries, adult male rates quadrupling those of adult females for body scarring and males maintaining larger stubs, probably because of the presence of copulatory organs housed in the base of the tail.