Exploring Body Injuries in the Horseshoe Whip Snake, Hemorrhois Hippocrepis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khalladi-Bpp Anexes-Arabic.Pdf

Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 107 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 108 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 109 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 110 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 111 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 112 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 113 The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria are intended to be an easily and widely understood system for classifying species at high risk of global extinction. The IUCN Red List is categorized in the following Categories: • Extinct (EX): A taxon is Extinct when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form. Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects 114 Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 • Extinct in the Wild (EW): A taxon is Extinct in the Wild when it is known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity or as a naturalized population (or populations) well outside the past range. A taxon is presumed Extinct in the Wild when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. -

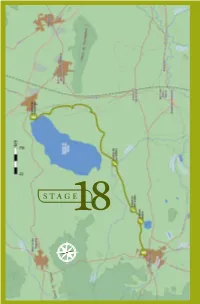

B I R D W a T C H I N G •

18 . F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS STAGE18 E S N O 158 BIRDWATCHING • GR-249 Great Path of Malaga F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS 18 . STAGE 18 Fuente de Piedra - Campillos L O C A T I O N he José Antonio Valverde Visitor´s Centre at the TReserva Natural de la Laguna de Fuente de Piedra is the starting point of Stage 18. Taking the direction south around the taken up mainly by olive trees and grain. eastern side of the salt water lagoon This type of environment will continue to you will be walking through farmland the end of this stage and it determines until the end of this stage in Campillos the species of birds which can be seen village. The 15, 7 km of Stage 18 will here. You will be crossing a stream and allow you to discover this wetland well then walking along the two lakes which known at national level in Spain, and will make your Stage 18 bird list fill cultivated farmland which creates a up with highly desirable species. The steppe-like environment. combination of wetland and steppe creates very valuable habitats with DESCRIPTION a rare composition of taxa unique at European level. ABOUT THE BIRDLIFE: Stage 18 begins at the northern tip HIGHLIGHTED SPECIES of the lagoon where you take direction Neither the length, diffi culty level or south through agricultural environment, elevation gain of this stage is particularly DID YOU KNOW? ecilio Garcia de la Leña, in Conversation 9th of “Historical Conversations of Malaga” published by Cristóbal Medina Conde (1726-1798) and entitled «About Animal Kingdom of Malaga and some Places in its Bishopric», Ccomments: «…In some lagoons, along sea shores and river banks some large and beautiful birds breed, called Flamingos and Phoenicopteros according to the ancients...», after a description of the bird´s anatomy he adds: «The Romans appreciated the bird greatly, especially its tongue which was served as an exquisite dish…». -

A New Miocene-Divergent Lineage of Old World Racer Snake from India

RESEARCH ARTICLE A New Miocene-Divergent Lineage of Old World Racer Snake from India Zeeshan A. Mirza1☯*, Raju Vyas2, Harshil Patel3☯, Jaydeep Maheta4, Rajesh V. Sanap1☯ 1 National Centre for Biological Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bangalore 560065, India, 2 505, Krishnadeep Towers, Mission Road, Fatehgunj, Vadodra 390002, Gujarat, India, 3 Department of Biosciences, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat-395007, Gujarat, India, 4 Shree cultural foundation, Ahmedabad 380004, Gujarat, India ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract A distinctive early Miocene-divergent lineage of Old world racer snakes is described as a new genus and species based on three specimens collected from the western Indian state of Gujarat. Wallaceophis gen. et. gujaratenesis sp. nov. is a members of a clade of old world racers. The monotypic genus represents a distinct lineage among old world racers is recovered as a sister taxa to Lytorhynchus based on ~3047bp of combined nuclear (cmos) and mitochondrial molecular data (cytb, ND4, 12s, 16s). The snake is distinct morphologi- cally in having a unique dorsal scale reduction formula not reported from any known colubrid snake genus. Uncorrected pairwise sequence divergence for nuclear gene cmos between OPEN ACCESS Wallaceophis gen. et. gujaratenesis sp. nov. other members of the clade containing old Citation: Mirza ZA, Vyas R, Patel H, Maheta J, world racers and whip snake is 21–36%. Sanap RV (2016) A New Miocene-Divergent Lineage of Old World Racer Snake from India. PLoS ONE 11 (3): e0148380. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148380 Introduction Editor: Ulrich Joger, State Natural History Museum, GERMANY Colubrid snakes are one of the most speciose among serpents with ~1806 species distributed across the world [1–5]. -

Tail Breakage and Predatory Pressure Upon Two Invasive Snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at Two Islands in the Western Mediterranean

Canadian Journal of Zoology Tail breakage and predatory pressure upon two invasive snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at two islands in the Western Mediterranean Journal: Canadian Journal of Zoology Manuscript ID cjz-2020-0261.R2 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 17-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Febrer-Serra, Maria; University of the Balearic Islands Lassnig, Nil; University of the Balearic Islands Colomar, Victor; Consorci per a la Recuperació de la Fauna de les Illes Balears Draft Sureda Gomila, Antoni; University of the Balearic Islands; Carlos III Health Institute, CIBEROBC Pinya Fernández, Samuel; University of the Balearic Islands, Biology Is your manuscript invited for consideration in a Special Not applicable (regular submission) Issue?: Zamenis scalaris, Hemorrhois hippocrepis, invasive snakes, predatory Keyword: pressure, Balearic Islands, frequency of tail breakage © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 34 Canadian Journal of Zoology 1 Tail breakage and predatory pressure upon two invasive snakes (Serpentes: 2 Colubridae) at two islands in the Western Mediterranean 3 4 M. Febrer-Serra, N. Lassnig, V. Colomar, A. Sureda, S. Pinya* 5 6 M. Febrer-Serra. Interdisciplinary Ecology Group. University of the Balearic Islands, 7 Ctra. Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain. E-mail address: 8 [email protected]. 9 N. Lassnig. Interdisciplinary Ecology Group. University of the Balearic Islands, Ctra. 10 Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain. E-mail address: 11 [email protected]. 12 V. Colomar. Consortium for the RecoveryDraft of Fauna of the Balearic Islands (COFIB). 13 Government of the Balearic Islands, Spain. -

Observations of Marine Swimming in Malpolon Monspessulanus

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 593-596 (2021) (published online on 29 March 2021) Snake overboard! Observations of marine swimming in Malpolon monspessulanus Grégory Deso1,*, Xavier Bonnet2, Cornélius De Haan3, Gilles Garnier4, Nicolas Dubos5, and Jean-Marie Ballouard6 The ability to swim is widespread in snakes and not The diversity of fundamentally terrestrial snake restricted to aquatic (freshwater) or marine species species that colonised islands worldwide, including (Jayne, 1985, 1988). A high tolerance to hypernatremia remote ones (e.g., the Galapagos Archipelago), shows (i.e., high concentration of sodium in the blood) enables that these reptiles repeatedly achieved very long and some semi-aquatic freshwater species to use brackish successful trips across the oceans (Thomas, 1997; and saline habitats. In coastal populations, snakes may Martins and Lillywhite, 2019). However, we do not even forage at sea (Tuniyev et al., 2011; Brischoux and know how snakes reached remote islands. Did they Kornilev, 2014). Terrestrial species, however, are rarely actively swim, merely float at the surface, or were observed in the open sea. While snakes are particularly they transported by drifting rafts? We also ignore the resistant to fasting (Secor and Diamond, 2000), long trips mechanisms that enable terrestrial snakes to survive in the marine environment are metabolically demanding during long periods at sea and how long they can do so. (prolonged locomotor efforts entail substantial energy Terrestrial tortoises travel hundreds of kilometres, can expense) and might be risky (Lillywhite, 2014). float for weeks in ocean currents, and can sometimes Limited freshwater availability might compromise the survive in hostile conditions without food and with hydromineral balance of individuals, even in amphibious limited access to freshwater (Gerlach et al., 2006). -

Contents Herpetological Journal

British Herpetological Society Herpetological Journal Volume 31, Number 3, 2021 Contents Full papers Killing them softly: a review on snake translocation and an Australian case study 118-131 Jari Cornelis, Tom Parkin & Philip W. Bateman Potential distribution of the endemic Short-tailed ground agama Calotes minor (Hardwicke & Gray, 132-141 1827) in drylands of the Indian sub-continent Ashish Kumar Jangid, Gandla Chethan Kumar, Chandra Prakash Singh & Monika Böhm Repeated use of high risk nesting areas in the European whip snake, Hierophis viridiflavus 142-150 Xavier Bonnet, Jean-Marie Ballouard, Gopal Billy & Roger Meek The Herpetological Journal is published quarterly by Reproductive characteristics, diet composition and fat reserves of nose-horned vipers (Vipera 151-161 the British Herpetological Society and is issued free to ammodytes) members. Articles are listed in Current Awareness in Marko Anđelković, Sonja Nikolić & Ljiljana Tomović Biological Sciences, Current Contents, Science Citation Index and Zoological Record. Applications to purchase New evidence for distinctiveness of the island-endemic Príncipe giant tree frog (Arthroleptidae: 162-169 copies and/or for details of membership should be made Leptopelis palmatus) to the Hon. Secretary, British Herpetological Society, The Kyle E. Jaynes, Edward A. Myers, Robert C. Drewes & Rayna C. Bell Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK. Instructions to authors are printed inside the Description of the tadpole of Cruziohyla calcarifer (Boulenger, 1902) (Amphibia, Anura, 170-176 back cover. All contributions should be addressed to the Phyllomedusidae) Scientific Editor. Andrew R. Gray, Konstantin Taupp, Loic Denès, Franziska Elsner-Gearing & David Bewick A new species of Bent-toed gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Cyrtodactylus Gray, 1827) from the Garo 177-196 Hills, Meghalaya State, north-east India, and discussion of morphological variation for C. -

A Survey on Non-Venomous Snakes in Kashan (Central Iran)

J. Biol. Today's World. 2016 Apr; 5 (4): 65-75 ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ Journal of Biology and Today's World Journal home page: http://journals.lexispublisher.com/jbtw Received: 09 March 2016 • Accepted: 22 April 2016 Research doi:10.15412/J.JBTW.01050402 A survey on Non-Venomous Snakes in Kashan (Central Iran) Rouhullah Dehghani1, Nasrullah Rastegar pouyani2, Bita Dadpour3*, Dan Keyler4, Morteza Panjehshahi5, Mehrdad Jazayeri5, Omid Mehrpour6, Amir Habibi Tamijani7 1 Social Determinants of Health (SDH) Research Center and Department of Environment Health, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran 2 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran 3 Addiction Research Centre, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran 4 Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN, United States 5 Health Center of Kashan University Medical Sciences and Health Services, Kashan, Iran 6 Atherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Research Center, Birjand University of Medical Science, Medical Toxicology and Drug Abuse Research Center, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran 7 Legal Medicine Research Center, Legal Medicine Organization, Tehran, Iran *Correspondence should be addressed to Bita Dadpour, Addiction Research Centre, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran; Tell: +985118525315; Fax: +985118525315; Email: [email protected]. ABSTRACT Due to the importance of animal bites in terms of health impacts , potential medical consequences, and the necessity of proper differentiation between venomous and non-venomous snake species, this study was conducted with the aim of identifying non-venomous, or fangless snakes, in Kashan as a major city in central Iran during a three-year period (2010- 2012). -

Strasbourg, 22 May 2002

Strasbourg, 21 October 2015 T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 [Inf18e_2015.docx] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Standing Committee 35th meeting Strasbourg, 1-4 December 2015 GROUP OF EXPERTS ON THE CONSERVATION OF AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES 1-2 July 2015 Bern, Switzerland - NATIONAL REPORTS - Compilation prepared by the Directorate of Democratic Governance / The reports are being circulated in the form and the languages in which they were received by the Secretariat. This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 - 2 – CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE __________ 1. Armenia / Arménie 2. Austria / Autriche 3. Belgium / Belgique 4. Croatia / Croatie 5. Estonia / Estonie 6. France / France 7. Italy /Italie 8. Latvia / Lettonie 9. Liechtenstein / Liechtenstein 10. Malta / Malte 11. Monaco / Monaco 12. The Netherlands / Pays-Bas 13. Poland / Pologne 14. Slovak Republic /République slovaque 15. “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” / L’« ex-République yougoslave de Macédoine » 16. Ukraine - 3 - T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 ARMENIA / ARMENIE NATIONAL REPORT OF REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA ON NATIONAL ACTIVITIES AND INITIATIVES ON THE CONSERVATION OF AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES GENERAL INFORMATION ON THE COUNTRY AND ITS BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Armenia is a small landlocked mountainous country located in the Southern Caucasus. Forty four percent of the territory of Armenia is a high mountainous area not suitable for inhabitation. The degree of land use is strongly unproportional. The zones under intensive development make 18.2% of the territory of Armenia with concentration of 87.7% of total population. -

Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco: a Taxonomic Update and Standard Arabic Names

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 1-14 (2021) (published online on 08 January 2021) Checklist of amphibians and reptiles of Morocco: A taxonomic update and standard Arabic names Abdellah Bouazza1,*, El Hassan El Mouden2, and Abdeslam Rihane3,4 Abstract. Morocco has one of the highest levels of biodiversity and endemism in the Western Palaearctic, which is mainly attributable to the country’s complex topographic and climatic patterns that favoured allopatric speciation. Taxonomic studies of Moroccan amphibians and reptiles have increased noticeably during the last few decades, including the recognition of new species and the revision of other taxa. In this study, we provide a taxonomically updated checklist and notes on nomenclatural changes based on studies published before April 2020. The updated checklist includes 130 extant species (i.e., 14 amphibians and 116 reptiles, including six sea turtles), increasing considerably the number of species compared to previous recent assessments. Arabic names of the species are also provided as a response to the demands of many Moroccan naturalists. Keywords. North Africa, Morocco, Herpetofauna, Species list, Nomenclature Introduction mya) led to a major faunal exchange (e.g., Blain et al., 2013; Mendes et al., 2017) and the climatic events that Morocco has one of the most varied herpetofauna occurred since Miocene and during Plio-Pleistocene in the Western Palearctic and the highest diversities (i.e., shift from tropical to arid environments) promoted of endemism and European relict species among allopatric speciation (e.g., Escoriza et al., 2006; Salvi North African reptiles (Bons and Geniez, 1996; et al., 2018). Pleguezuelos et al., 2010; del Mármol et al., 2019). -

Elaphe Scalaris

Keeping and breeding the Ladder snake, ELAPHE SCALARIS KevinJ. Hingley cally around 1.2 metres in length, though some can 22 Bushe:,,fields Road, Dudley, West reach 1.6 metres. Midla11ds, DY:1 2LP, E11gla11d. • CAPTIVE HUSBANDRY • INTRODUCTION If you want an easy to keep and breed ratsnake this is The Ladder snake, Elaphe scalaris, is not a ratsnake for one such species, but of course its temperament could the faint-hearted keeper.Whilst they make a good ter be better. Unlike some other European and North rarium subject and are not difficult to keep or breed, American Elaphe species I have kept the Ladder snake most specimens are lively, fast-moving and nervous is not put off its food by higher temperatures of around snakes which rarely hesitate to bite at their own dis 30°C in the warmest summer months - in fact they cretion. If you want a tame snake or one that is not seem to relish it. I began keeping this species with two likely to bite you, don't buy a Ladder snake. hatchlings (one of each sex) which were given to me As far as European ratsnakes are concerned, the Ladder in 1990 and in exchange the following year I gave their snake is considered to be the only species of truly breeder a baby female Leopard snake.The two babies European origin, the other species being thought to posed no problems to rear and were kept initially in have originated in Asia and have since extended their small separate boxes with paper towelling substrate,a ranges ever westward into Europe with time.As such, cardboard tube for a hiding place and a small dish of £ scalaris is confined to most of Portugal and Spain, a water.The temperature was around 28°C,and as they few Mediterranean islands (including lies d'Hyeres and grew they were simply transferred to increasingly lar Minorca) and southern France.The young of this spe ger quarters until they were adult, and then they were cies give it its common name, for they bear the pattern placed in a fauna box each and kept in the warmest of a "ladder" along their back, but this fades with age part of my snake room. -

Faunistics Study of Snakes of Western Golestan Province M

ن،ن، ز و ﯾر و ن ن د زد و ن ١٩١٩١٩ وو ٢٠٢٠٢٠ ١٣٨٨١٣٨٨١٣٨٨ ﻣﻄﺎﻟﻌﻪ ﻓﻮن ﻣﺎرﻫﺎي ﻏﺮب اﺳﺘﺎن ﮔﻠﺴﺘﺎن ﻣﻴﻨﺎ رﻣﻀﺎﻧﻲ1 ، ﺣﺎﺟﻲ ﻗﻠﻲ ﻛﻤﻲ2 ، ﻧﺎﻫﻴﺪ اﺣﻤﺪ ﭘﻨﺎه*3 ﭼﻜﻴﺪه : : ﻫﺪف ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻖ ﺣﺎﺿﺮ ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﻓﻮﻧﺴﺘﻴﻚ ﻣﺎرﻫﺎي ﻣﻨﺎﻃﻖ ﻏﺮﺑﻲ اﺳﺘﺎن ﮔﻠﺴﺘﺎن ( از ﺷﻬﺮ ﮔﺮﮔﺎن ﺗﺎ ﻣﺮز اﺳﺘﺎن ﻣﺎزﻧﺪران) ﺑﺎ ﺗﻮﺟﻪ ﺑﻪ ﺻﻔﺎت رﻳﺨﺖ ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ و ﺑﺎ ﻛﻤﻚ ﻛﻠﻴﺪﺷﻨﺎﺳﺎﻳﻲ اﺳﺖ . در اﻳﻦ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻖ ﻛﻪ از اوا ﻳﻞ ﻣﺮدادﻣﺎه 1387 ﺗﺎ آﺧﺮﻣﺮداد 1388 ﺑﻪ ﻃﻮل اﻧﺠﺎﻣﻴﺪ، ﺗﻌﺪاد 36 ﻧﻤﻮﻧﻪ از اﻳﻦ ﻣﻨﺎﻃﻖ ﺟﻤﻊ آوري وﻣﻮرد ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﻗﺮارﮔﺮﻓﺖ . ﻧﻤﻮﻧﻪ ﻫﺎي ﺷﻨﺎﺳﺎﻳﻲ ﺷﺪه ﺷﺎﻣﻞ ﻳﺎزده ﮔﻮﻧﻪ ي ﻣﺨﺘﻠﻒ درﭼﻬﺎر ﺧﺎﻧﻮاده وده ﺟﻨﺲ ﺑﻮد ﻛﻪ ﻋﺒﺎرﺗﻨﺪ از : ﻣﺎرﻛﺮﻣﻲ ﺷﻜﻞ Typhlops vermicularis از ﺧﺎﻧﻮاده ي Typhlopidae، ﻣﺎر ﭼﻠﻴﭙﺮ Natrix tessellata tessellata ، ﻣﺎر آﺑﻲ Natrix natrix natrix ، ﮔﻮﻧﺪﻣﺎر Elaphe dione dione، ﻣﺎرﭘﻠﻨﮕﻲ Hemorrhois ravergieri ، ﻣﺎرﻣﻮﺷﺨﻮر اﻳﺮاﻧﻲ Zamenis persica ﻣﺎرآﺗﺸﻲ Dolichophis jugularis ، ﻗﻤﭽﻪ ﻣﺎر Platyceps najadum ، ﺳﻮﺳﻦ ﻣﺎر Telescopus fallax ibericus ﻫﻤﮕﻲ ﻣﺘﻌﻠﻖ ﺑﻪ ﺧﺎﻧﻮاده ي Colubridae ، ﻛﻔﭽﻪ ﻣﺎر Naja oxiana از ﺧﺎﻧﻮاده ي Elapidae ،اﻓﻌﻲ ﻗﻔﻘﺎزي Gloydius caucasicus halys ازﺧﺎﻧﻮاده ي Viperidae . ﺳﭙﺲ ﻧﻘﺸﻪ ي ﭘﺮاﻛﻨﺪﮔﻲ ﻫﺮ ﮔﻮﻧﻪ ﺗﺮﺳﻴﻢ ﺷﺪ . واژه ﻫﺎي ﻛﻠﻴﺪي: ﻣﺎر، ﻓﻮﻧﺴﺘﻴﻚ ، ﮔﻠﺴﺘﺎن -1 اﺳﺘﺎدﻳﺎر داﻧﺸﮕﺎه آزاد اﺳﻼﻣﻲ واﺣﺪ آﺷﺘﻴﺎن -2 اﺳﺘﺎدﻳﺎ ر داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﮔﻠﺴﺘﺎن -3 داﻧﺸﺠﻮي ﻛﺎرﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ارﺷﺪ رﺷﺘﻪ ﻋﻠﻮم ﺟﺎﻧﻮري داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﭘﻴﺎم ﻧﻮر، ﻣﺮﻛﺰ ﺗﻬﺮان 1 ﻣﻘﺪﻣﻪ : : ﻣﺎرﻫﺎ ازﺟﻨﺒﻪ ﻫﺎي اﻗﺘﺼﺎدي و ﺑﻬﺪاﺷﺘﻲ ﻣﺎﻧﻨﺪ ﺗﻮﻟﻴﺪ ﭘﺎدزﻫﺮ، اﺳﺘﻔﺎده از ﭘﻮﺳﺖ آن ﻫﺎ درﺻﻨﺎﻳﻊ، ﺑﻪ ﻋﻨﻮان ﻳﻚ ﻣﻨﺒﻊ ﭘﺮوﺗﺌﻴﻨﻲ در ﺑﺮﺧﻲ ﻛﺸﻮرﻫﺎ و ﺑﻪ وﻳﮋه ﺟﺎﻳﮕﺎه ﻣﻬﻢ در اﻛﻮﺳﻴﺴﺘﻢ ﻫﺎ و زﻧﺠﻴﺮه ﻫﺎي ﻏﺬاﻳﻲ وﻛﻨﺘﺮل دﻓﻊ آﻓﺎت ﻛﺸﺎورزي، ﺣﺎﻳﺰ اﻫﻤﻴﺖ ﻫﺴﺘﻨﺪ 2( ). ﻣﺎرﻫﺎي اﻣﺮوزي، اﺳﺎﺳﺎً ﻳﻚ ﺷﻜﻞ، ﺑﻠﻨﺪ و ﺑﺎرﻳﻚ و ﺑﺪون اﻧﺪام ﺣﺮﻛﺘﻲ ﻫﺴﺘﻨﺪ( 14 ). -

Chemical Recognition of Snake Predators by Lizards in a Mediterranean Island

From tameness to wariness: chemical recognition of snake predators by lizards in a Mediterranean island Abraham Mencía*, Zaida Ortega* and Valentín Pérez-Mellado Department of Animal Biology, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Antipredatory defenses are maintained when benefit exceeds cost. A weak predation pressure may lead insular lizards to tameness. Podarcis lilfordi exhibits a high degree of insular tameness, which may explain its extinction from the main island of Menorca when humans introduced predators. There are three species of lizards in Menorca: the native P. lilfordi, only on the surrounding islets, and two introduced lizards in the main island, Scelarcis perspicillata and Podarcis siculus. In addition, there are three species of snakes, all introduced: one non-saurophagous (Natrix maura), one potentially non- saurophagous (Rhinechis scalaris) and one saurophagous (Macroprotodon mauritani- cus). We studied the reaction to snake chemical cues in five populations: (1) P. lilfordi of Colom, (2) P. lilfordi of Aire, (3) P. lilfordi of Binicodrell, (4) S. perspicillata, and (5) P. siculus, ordered by increasing level of predation pressure. The three snakes are present in the main island, while only R. scalaris is present in Colom islet, Aire and Binicodrell being snake-free islets. We aimed to assess the relationship between predation pressure and the degree of insular tameness regarding scent recognition. We hypothesized that P. lilfordi should show the highest degree of tameness, S. perspicillata should show intermediate responses, and P. siculus should show the highest wariness. Results are clear: neither P. lilfordi nor S. perspicillata recognize any of the snakes, while P.