Tail Breakage and Predatory Pressure Upon Two Invasive Snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at Two Islands in the Western Mediterranean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khalladi-Bpp Anexes-Arabic.Pdf

Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 107 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 108 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 109 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 110 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 111 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 112 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 113 The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria are intended to be an easily and widely understood system for classifying species at high risk of global extinction. The IUCN Red List is categorized in the following Categories: • Extinct (EX): A taxon is Extinct when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form. Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects 114 Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 • Extinct in the Wild (EW): A taxon is Extinct in the Wild when it is known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity or as a naturalized population (or populations) well outside the past range. A taxon is presumed Extinct in the Wild when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. -

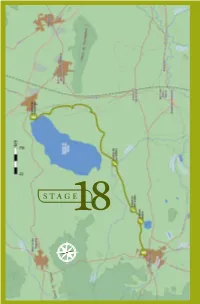

B I R D W a T C H I N G •

18 . F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS STAGE18 E S N O 158 BIRDWATCHING • GR-249 Great Path of Malaga F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS 18 . STAGE 18 Fuente de Piedra - Campillos L O C A T I O N he José Antonio Valverde Visitor´s Centre at the TReserva Natural de la Laguna de Fuente de Piedra is the starting point of Stage 18. Taking the direction south around the taken up mainly by olive trees and grain. eastern side of the salt water lagoon This type of environment will continue to you will be walking through farmland the end of this stage and it determines until the end of this stage in Campillos the species of birds which can be seen village. The 15, 7 km of Stage 18 will here. You will be crossing a stream and allow you to discover this wetland well then walking along the two lakes which known at national level in Spain, and will make your Stage 18 bird list fill cultivated farmland which creates a up with highly desirable species. The steppe-like environment. combination of wetland and steppe creates very valuable habitats with DESCRIPTION a rare composition of taxa unique at European level. ABOUT THE BIRDLIFE: Stage 18 begins at the northern tip HIGHLIGHTED SPECIES of the lagoon where you take direction Neither the length, diffi culty level or south through agricultural environment, elevation gain of this stage is particularly DID YOU KNOW? ecilio Garcia de la Leña, in Conversation 9th of “Historical Conversations of Malaga” published by Cristóbal Medina Conde (1726-1798) and entitled «About Animal Kingdom of Malaga and some Places in its Bishopric», Ccomments: «…In some lagoons, along sea shores and river banks some large and beautiful birds breed, called Flamingos and Phoenicopteros according to the ancients...», after a description of the bird´s anatomy he adds: «The Romans appreciated the bird greatly, especially its tongue which was served as an exquisite dish…». -

Observations of Marine Swimming in Malpolon Monspessulanus

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 593-596 (2021) (published online on 29 March 2021) Snake overboard! Observations of marine swimming in Malpolon monspessulanus Grégory Deso1,*, Xavier Bonnet2, Cornélius De Haan3, Gilles Garnier4, Nicolas Dubos5, and Jean-Marie Ballouard6 The ability to swim is widespread in snakes and not The diversity of fundamentally terrestrial snake restricted to aquatic (freshwater) or marine species species that colonised islands worldwide, including (Jayne, 1985, 1988). A high tolerance to hypernatremia remote ones (e.g., the Galapagos Archipelago), shows (i.e., high concentration of sodium in the blood) enables that these reptiles repeatedly achieved very long and some semi-aquatic freshwater species to use brackish successful trips across the oceans (Thomas, 1997; and saline habitats. In coastal populations, snakes may Martins and Lillywhite, 2019). However, we do not even forage at sea (Tuniyev et al., 2011; Brischoux and know how snakes reached remote islands. Did they Kornilev, 2014). Terrestrial species, however, are rarely actively swim, merely float at the surface, or were observed in the open sea. While snakes are particularly they transported by drifting rafts? We also ignore the resistant to fasting (Secor and Diamond, 2000), long trips mechanisms that enable terrestrial snakes to survive in the marine environment are metabolically demanding during long periods at sea and how long they can do so. (prolonged locomotor efforts entail substantial energy Terrestrial tortoises travel hundreds of kilometres, can expense) and might be risky (Lillywhite, 2014). float for weeks in ocean currents, and can sometimes Limited freshwater availability might compromise the survive in hostile conditions without food and with hydromineral balance of individuals, even in amphibious limited access to freshwater (Gerlach et al., 2006). -

Contents Herpetological Journal

British Herpetological Society Herpetological Journal Volume 31, Number 3, 2021 Contents Full papers Killing them softly: a review on snake translocation and an Australian case study 118-131 Jari Cornelis, Tom Parkin & Philip W. Bateman Potential distribution of the endemic Short-tailed ground agama Calotes minor (Hardwicke & Gray, 132-141 1827) in drylands of the Indian sub-continent Ashish Kumar Jangid, Gandla Chethan Kumar, Chandra Prakash Singh & Monika Böhm Repeated use of high risk nesting areas in the European whip snake, Hierophis viridiflavus 142-150 Xavier Bonnet, Jean-Marie Ballouard, Gopal Billy & Roger Meek The Herpetological Journal is published quarterly by Reproductive characteristics, diet composition and fat reserves of nose-horned vipers (Vipera 151-161 the British Herpetological Society and is issued free to ammodytes) members. Articles are listed in Current Awareness in Marko Anđelković, Sonja Nikolić & Ljiljana Tomović Biological Sciences, Current Contents, Science Citation Index and Zoological Record. Applications to purchase New evidence for distinctiveness of the island-endemic Príncipe giant tree frog (Arthroleptidae: 162-169 copies and/or for details of membership should be made Leptopelis palmatus) to the Hon. Secretary, British Herpetological Society, The Kyle E. Jaynes, Edward A. Myers, Robert C. Drewes & Rayna C. Bell Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK. Instructions to authors are printed inside the Description of the tadpole of Cruziohyla calcarifer (Boulenger, 1902) (Amphibia, Anura, 170-176 back cover. All contributions should be addressed to the Phyllomedusidae) Scientific Editor. Andrew R. Gray, Konstantin Taupp, Loic Denès, Franziska Elsner-Gearing & David Bewick A new species of Bent-toed gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Cyrtodactylus Gray, 1827) from the Garo 177-196 Hills, Meghalaya State, north-east India, and discussion of morphological variation for C. -

Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles of Morocco: a Taxonomic Update and Standard Arabic Names

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 1-14 (2021) (published online on 08 January 2021) Checklist of amphibians and reptiles of Morocco: A taxonomic update and standard Arabic names Abdellah Bouazza1,*, El Hassan El Mouden2, and Abdeslam Rihane3,4 Abstract. Morocco has one of the highest levels of biodiversity and endemism in the Western Palaearctic, which is mainly attributable to the country’s complex topographic and climatic patterns that favoured allopatric speciation. Taxonomic studies of Moroccan amphibians and reptiles have increased noticeably during the last few decades, including the recognition of new species and the revision of other taxa. In this study, we provide a taxonomically updated checklist and notes on nomenclatural changes based on studies published before April 2020. The updated checklist includes 130 extant species (i.e., 14 amphibians and 116 reptiles, including six sea turtles), increasing considerably the number of species compared to previous recent assessments. Arabic names of the species are also provided as a response to the demands of many Moroccan naturalists. Keywords. North Africa, Morocco, Herpetofauna, Species list, Nomenclature Introduction mya) led to a major faunal exchange (e.g., Blain et al., 2013; Mendes et al., 2017) and the climatic events that Morocco has one of the most varied herpetofauna occurred since Miocene and during Plio-Pleistocene in the Western Palearctic and the highest diversities (i.e., shift from tropical to arid environments) promoted of endemism and European relict species among allopatric speciation (e.g., Escoriza et al., 2006; Salvi North African reptiles (Bons and Geniez, 1996; et al., 2018). Pleguezuelos et al., 2010; del Mármol et al., 2019). -

Elaphe Scalaris

Keeping and breeding the Ladder snake, ELAPHE SCALARIS KevinJ. Hingley cally around 1.2 metres in length, though some can 22 Bushe:,,fields Road, Dudley, West reach 1.6 metres. Midla11ds, DY:1 2LP, E11gla11d. • CAPTIVE HUSBANDRY • INTRODUCTION If you want an easy to keep and breed ratsnake this is The Ladder snake, Elaphe scalaris, is not a ratsnake for one such species, but of course its temperament could the faint-hearted keeper.Whilst they make a good ter be better. Unlike some other European and North rarium subject and are not difficult to keep or breed, American Elaphe species I have kept the Ladder snake most specimens are lively, fast-moving and nervous is not put off its food by higher temperatures of around snakes which rarely hesitate to bite at their own dis 30°C in the warmest summer months - in fact they cretion. If you want a tame snake or one that is not seem to relish it. I began keeping this species with two likely to bite you, don't buy a Ladder snake. hatchlings (one of each sex) which were given to me As far as European ratsnakes are concerned, the Ladder in 1990 and in exchange the following year I gave their snake is considered to be the only species of truly breeder a baby female Leopard snake.The two babies European origin, the other species being thought to posed no problems to rear and were kept initially in have originated in Asia and have since extended their small separate boxes with paper towelling substrate,a ranges ever westward into Europe with time.As such, cardboard tube for a hiding place and a small dish of £ scalaris is confined to most of Portugal and Spain, a water.The temperature was around 28°C,and as they few Mediterranean islands (including lies d'Hyeres and grew they were simply transferred to increasingly lar Minorca) and southern France.The young of this spe ger quarters until they were adult, and then they were cies give it its common name, for they bear the pattern placed in a fauna box each and kept in the warmest of a "ladder" along their back, but this fades with age part of my snake room. -

Chemical Recognition of Snake Predators by Lizards in a Mediterranean Island

From tameness to wariness: chemical recognition of snake predators by lizards in a Mediterranean island Abraham Mencía*, Zaida Ortega* and Valentín Pérez-Mellado Department of Animal Biology, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Antipredatory defenses are maintained when benefit exceeds cost. A weak predation pressure may lead insular lizards to tameness. Podarcis lilfordi exhibits a high degree of insular tameness, which may explain its extinction from the main island of Menorca when humans introduced predators. There are three species of lizards in Menorca: the native P. lilfordi, only on the surrounding islets, and two introduced lizards in the main island, Scelarcis perspicillata and Podarcis siculus. In addition, there are three species of snakes, all introduced: one non-saurophagous (Natrix maura), one potentially non- saurophagous (Rhinechis scalaris) and one saurophagous (Macroprotodon mauritani- cus). We studied the reaction to snake chemical cues in five populations: (1) P. lilfordi of Colom, (2) P. lilfordi of Aire, (3) P. lilfordi of Binicodrell, (4) S. perspicillata, and (5) P. siculus, ordered by increasing level of predation pressure. The three snakes are present in the main island, while only R. scalaris is present in Colom islet, Aire and Binicodrell being snake-free islets. We aimed to assess the relationship between predation pressure and the degree of insular tameness regarding scent recognition. We hypothesized that P. lilfordi should show the highest degree of tameness, S. perspicillata should show intermediate responses, and P. siculus should show the highest wariness. Results are clear: neither P. lilfordi nor S. perspicillata recognize any of the snakes, while P. -

Long- and Short-Term Impact of Temperature on Snake Detection in the Wild: Further Evidence from the Snake Hemorrhois Hippocrepis

Acta Herpetologica 5(2): 143-150, 2010 Long- and short-term impact of temperature on snake detection in the wild: further evidence from the snake Hemorrhois hippocrepis Francisco J. Zamora-Camacho1,*, Gregorio Moreno-Rueda2, Juan M. Pleguezuelos1 1 Departamento de Biología Animal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Granada, E-18071, Grana- da, Spain. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Estación Experimental de Zonas Áridas (CSIC), La Cañada de San Urbano, Ctra. Sacramento s/n, E-04120, Almería, Spain. Submitted on: 2010, 25th February; revised on: 2010, 15th, August; accepted on: 2010, 22th, October. Abstract. Global change is causing an average temperature increment which affects several aspects of organisms’ biology, especially in ectotherms. Nevertheless, there is still scant knowledge about how this change is affecting reptiles. This paper shows that, the higher average temperature in a year, the more individuals of the snake Hem- orrhois hippocrepis are found in the field, because temperature increases the snakes’ activity. Furthermore, the quantity of snakes found was also correlated with the tem- perature of the previous years. Our results suggest that environmental temperature increases the population size of this species, which could benefit from the tempera- ture increment caused by climatic change. However, we did not find an increase in population size with the advance of years, suggesting that other factors have negatively impacted on this species, balancing the effect of increasing temperature. Keywords. -

Western Sand Racer – Psammodromus Occidentalis Fitze, González-Jimena, San-José, San Mauro Y Zardoya, 2012

Fitze, P. S. (2012). Western Sand Racer – Psammodromus occidentalis. En: Enciclopedia Virtual de los Vertebrados Españoles. Salvador, A., Marco, A. (Eds.). Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid. http://www.vertebradosibericos.org/ Western Sand Racer – Psammodromus occidentalis Fitze, González-Jimena, San-José, San Mauro y Zardoya, 2012 Patrick S. Fitze Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC) Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología (CSIC) Fundación ARAID Université de Lausanne Publication date: 25-10-2012 © P. S. Fitze ENCICLOPEDIA VIRTUAL DE LOS VERTEBRADOS ESPAÑOLES Sociedad de Amigos del MNCN – MNCN - CSIC Fitze, P. S. (2012). Western Sand Racer – Psammodromus occidentalis. En: Enciclopedia Virtual de los Vertebrados Españoles. Salvador, A., Marco, A. (Eds.). Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid. http://www.vertebradosibericos.org/ Synonyms Psammodromus edwardsii (Barbosa du Bocage, 1863, p. 333); Psammodromus hispanicus (López Seoane, 1877, p.352; Lataste, 1878, p. 694; Boscá, 1880, p. 273); Psammodromus hispanicus hispanicus (Mertens, 1925, p. 81 – 84; 1926, p. 155). Common Names Catalan: Sargantana occidental ibèrica; French: Psammodrome occidental; German: Westlicher Sandläufer; Portuguese: Lagartixa-do-mato occidental; Spanish: Lagartija occidental ibérica. History of Nomenclature Up until 2010, P. occidentalis had been classified as belonging to P. hispanicus. In 2010, this species was characterized by Fitze et al. (Fitze et al., 2010; San Jose Garcia et al., 2010) based on molecular, phenotypic, and ecological analyses (Fitze et al., 2011, 2012). Type Locality Terra typica is central Spain; Colmenar del Arroyo, Madrid (Fitze et al., 2012), where both the holotype and paratypes were captured. The holotype was deposited at the National Natural History Museum of Spain (MNCN-CSIC, Madrid) and the paratypes at MNCN-CSIC and at the British Natural History Museum (NHM, London) (Fitze et al., 2012). -

2021Alkinsdmscres.Pdf with Marking the Unmarkable

Bangor University MASTERS BY RESEARCH Habitat Selection of a Non-Native Snake: Implications for Future Management of Zamenis longissimus in Colwyn Bay, North Wales Alkins, Dev Award date: 2021 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Habitat Selection of a Non-Native Snake: Implications for Future Management of Zamenis longissimus in Colwyn Bay, North Wales Devlan Alkins Supervisor: Dr Wolfgang Wüster Bangor University Keywords: Non-native, Invasive, Habitat Selection, Prey Availability, Colwyn Bay, Aesculapian, Zamenis longissimus I hereby declare that this thesis is the results of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. All other sources are acknowledged by bibliographic references. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree unless, as agreed by the University, for approved dual awards. -

Deliberate Tail Loss in Dolichophis Caspius and Natrix Tessellata (Serpentes: Colubridae) with a Brief Review of Pseudoautotomy in Contemporary Snake Families

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 12 (2): 367-372 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2016 Article No.: e162503 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Deliberate tail loss in Dolichophis caspius and Natrix tessellata (Serpentes: Colubridae) with a brief review of pseudoautotomy in contemporary snake families Jelka CRNOBRNJA-ISAILOVIĆ1,2,*, Jelena ĆOROVIĆ2 and Balint HALPERN3 1. Faculty of Sciences and Mathematics, University of Niš, Višegradska 33, 18000 Niš, Serbia. 2. Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, University of Belgrade, Despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia. 3. MME BirdLife Hungary, Költő u. 21, 1121 Budapest, Hungary. * Corresponding author, J. Crnobrnja-Isailović, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 22. April 2015 / Accepted: 16. July 2015 / Available online: 29. July 2015 / Printed: December 2016 Abstract. Deliberate tail loss was recorded for the first time in three large whip snakes (Dolichophis caspius) and one dice snake (Natrix tessellata). Observations were made in different years and in different locations. In all cases the tail breakage happened while snakes were being handled by researchers. Pseudoautotomy was confirmed in one large whip snake by an X-Ray photo of a broken piece of the tail, where intervertebral breakage was observed. This evidence and literature data suggest that many colubrid species share the ability for deliberate tail loss. However, without direct observation or experiment it is not possible to prove a species’ ability for pseudoautotomy, as a broken tail could also be evidence of an unsuccessful predator attack, resulting in a forcefully broken distal part of the tail. Key words: deliberate tail loss, pseudoautotomy, Colubridae, Dolichophis caspius, Natrix tessellate. -

Naval Radio Station Jim Creek

Naval Station Rota Reptile and Amphibian Survey September 2010 Prepared by: Chris Petersen Naval Facilities Engineering Command Atlantic Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Study Site ........................................................................................................... 1 Materials and Methods ............................................................................................ 2 Field Survey Techniques.................................................................................... 2 Vegetation Community Mapping ...................................................................... 3 Results ..................................................................................................................... 4 Amphibians ........................................................................................................ 4 Reptiles .............................................................................................................. 8 Area Profiles ...................................................................................................... 8 Core/Industrial Area...................................................................................... 8 Golf Course Area .......................................................................................... 10 Airfield/Flightline Area ................................................................................ 10 Western Arroyo