Is Forest Certification Targeting Areas of High Biodiversity in Cork Oak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Portugal: Birds, Alpine Flora & Prehistoric

Wild Portugal: Birds, Alpine Flora & Prehistoric Art Naturetrek Tour Report 14 – 21 July 2015 Ocellated Lizard Marsh Gentian White-rumped Swift Purple Shot Copper Report compiled by Philip Thompson Images by Tom Mabbett Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Wild Portugal: Birds, Alpine Flora & Prehistoric Art Tour Report Tour Participants: Philip Thompson & Tom Mabbett (leaders) with 15 Naturetrek clients Day 1 Tuesday 14th July With our safe mid-afternoon arrival into Porto airport, the formalities of collecting the minibuses were completed and, eventually, we were on our way for a direct transfer to our first hotel, based in the historic town of Castelo Rodrigo. A refreshment stop on the way was taken; it was something of a shock to the system as we stepped out of the air-conditioned vehicles into 38˚C! Fortunately, this was a very dry heat with non-existent humidity and not too taxing. Having arrived at the hotel, we were soon assigned our various rooms, spread among the three houses that make up the comfortable accommodation. After a pleasant dinner, we retired to rest up and prepare for an early start the next day. Day 2 Wednesday 15th July An early start was taken today in order to make the best use of the cooler conditions at the start of the day, and to enable a return to the hotel in the heat of the late afternoon for a swim and relax. We began with a drive to an area of arable cultivation where a small population of Little Bustards are known to occur. -

Bonelli's Eagle

# 017 Bird-o-soar 21 May 2018 BONELLI’S EAGLE Records of predation on Varanus griseus and Ptyonoprogne concolor by Aquila fasciata in Agolai, Jodhpur, India IUCN Red List: Least Concern (BirdLife International 2016) Images of Bonelli’s Eagle at Agolai, Jodhpur. (A) ventro-lateral view (B) dorsal view from top (C) a fresh predation of Dusky Crag Martin catch in flight (D) another predation of a Desert Monitor was sighted near to the Bonelli’s Eagle nest Prey-predator interactions are rarely observed in the field, and most attempts to identify and quantify their occurrence have Aves focused on a narrow range of species. Raptors typically hunt and [Class of Birds] kill their prey. Small lizards and frogs are preyed upon by a great Accipitriformes variety of animals (Duellman & Trueb 1986; Greene 1988; Zug [Order of diurnal birds of prey] 1993). Here we have recorded a predation upon Desert Monitor Accipitridae Varanus griseus and Dusky Crag Martin Ptyonoprogne concolor [Family of Hawks and by Bonelli’s Eagle Aquila fasciata in Thar Desert of Rajasthan. Eagles] Bonelli’s Eagle is known to be a characteristic local and Aquila fasciatus [Bonelli’s Eagle] scarce resident breeding raptor species in countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and the Middle East (Gensbol 1987; Species described by Vieillot in 1822 Rocamora 1994). This raptor is also found commonly in the Zoo’s Print Vol. 33 | No. 5 17 # 017 Bird-o-soar 21 May 2018 southeastern Palaearctic region, Indochina, southeastern China and Indonesia (Cramp & Simmons 1980; BirdLife International 2018). It plays a key role as top predator in natural ecosystems (Rocamora 1994). -

Hungary & Transylvania

Although we had many exciting birds, the ‘Bird of the trip’ was Wallcreeper in 2015. (János Oláh) HUNGARY & TRANSYLVANIA 14 – 23 MAY 2015 LEADER: JÁNOS OLÁH Central and Eastern Europe has a great variety of bird species including lots of special ones but at the same time also offers a fantastic variety of different habitats and scenery as well as the long and exciting history of the area. Birdquest has operated tours to Hungary since 1991, being one of the few pioneers to enter the eastern block. The tour itinerary has been changed a few times but nowadays the combination of Hungary and Transylvania seems to be a settled and well established one and offers an amazing list of European birds. This tour is a very good introduction to birders visiting Europe for the first time but also offers some difficult-to-see birds for those who birded the continent before. We had several tour highlights on this recent tour but certainly the displaying Great Bustards, a majestic pair of Eastern Imperial Eagle, the mighty Saker, the handsome Red-footed Falcon, a hunting Peregrine, the shy Capercaillie, the elusive Little Crake and Corncrake, the enigmatic Ural Owl, the declining White-backed Woodpecker, the skulking River and Barred Warblers, a rare Sombre Tit, which was a write-in, the fluty Red-breasted and Collared Flycatchers and the stunning Wallcreeper will be long remembered. We recorded a total of 214 species on this short tour, which is a respectable tally for Europe. Amongst these we had 18 species of raptors, 6 species of owls, 9 species of woodpeckers and 15 species of warblers seen! Our mammal highlight was undoubtedly the superb views of Carpathian Brown Bears of which we saw ten on a single afternoon! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Hungary & Transylvania 2015 www.birdquest-tours.com We also had a nice overview of the different habitats of a Carpathian transect from the Great Hungarian Plain through the deciduous woodlands of the Carpathian foothills to the higher conifer-covered mountains. -

Turkey Birding Eastern Anatolia Th Th 10 June to 20 June 2021 (11 Days)

Turkey Birding Eastern Anatolia th th 10 June to 20 June 2021 (11 days) Caspian Snowcock by Alihan Vergiliel Turkey, a country the size of Texas, is a spectacular avian and cultural crossroads. This fascinating nation boasts an ancient history, from even before centuries of Greek Roman and Byzantine domination, through the 500-year Ottoman Empire and into the modern era. Needless to say, with such a pedigree the country holds some very impressive archaeological and cultural sites. Our tour of Eastern Turkey starts in the eastern city of Van, formerly known as Tuspa and 3,000 years ago the capital city of the Urartians. Today there are historical structures from the Seljuk and Ottoman periods, and Urartian artifacts can be seen at its archaeological museum. RBL Turkey Itinerary 2 However, it is the birds that are of primary interest to us as here, at the eastern limits of the Western Palearctic, we expect to find some very special and seldom-seen species, including Mountain ‘Caucasian’ Chiffchaff, Green Warbler, Mongolian Finch and Grey-headed Bunting. Around the shores of Lake Van we will seek out Moustached and Paddyfield Warblers in the dense reed beds, while on the lake itself, our targets include Marbled Teal, the threatened White-headed Duck, Dalmatian Pelican, Pygmy Cormorant and Armenian Gull, plus a selection of waders that may include Terek and Broad-billed Sandpiper. As we move further north-east into the steppe and semi desert areas, we will attempt to find Great Bustards and Demoiselle Cranes, with a potential supporting cast of Montagu’s Harrier, Steppe Eagle, the exquisite Citrine Wagtail and Twite, to name but a few. -

Khalladi-Bpp Anexes-Arabic.Pdf

Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 107 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 108 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 109 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 110 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 111 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 112 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 113 The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria are intended to be an easily and widely understood system for classifying species at high risk of global extinction. The IUCN Red List is categorized in the following Categories: • Extinct (EX): A taxon is Extinct when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form. Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects 114 Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 • Extinct in the Wild (EW): A taxon is Extinct in the Wild when it is known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity or as a naturalized population (or populations) well outside the past range. A taxon is presumed Extinct in the Wild when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. -

B I R D W a T C H I N G •

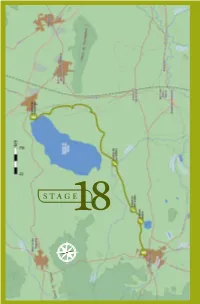

18 . F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS STAGE18 E S N O 158 BIRDWATCHING • GR-249 Great Path of Malaga F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS 18 . STAGE 18 Fuente de Piedra - Campillos L O C A T I O N he José Antonio Valverde Visitor´s Centre at the TReserva Natural de la Laguna de Fuente de Piedra is the starting point of Stage 18. Taking the direction south around the taken up mainly by olive trees and grain. eastern side of the salt water lagoon This type of environment will continue to you will be walking through farmland the end of this stage and it determines until the end of this stage in Campillos the species of birds which can be seen village. The 15, 7 km of Stage 18 will here. You will be crossing a stream and allow you to discover this wetland well then walking along the two lakes which known at national level in Spain, and will make your Stage 18 bird list fill cultivated farmland which creates a up with highly desirable species. The steppe-like environment. combination of wetland and steppe creates very valuable habitats with DESCRIPTION a rare composition of taxa unique at European level. ABOUT THE BIRDLIFE: Stage 18 begins at the northern tip HIGHLIGHTED SPECIES of the lagoon where you take direction Neither the length, diffi culty level or south through agricultural environment, elevation gain of this stage is particularly DID YOU KNOW? ecilio Garcia de la Leña, in Conversation 9th of “Historical Conversations of Malaga” published by Cristóbal Medina Conde (1726-1798) and entitled «About Animal Kingdom of Malaga and some Places in its Bishopric», Ccomments: «…In some lagoons, along sea shores and river banks some large and beautiful birds breed, called Flamingos and Phoenicopteros according to the ancients...», after a description of the bird´s anatomy he adds: «The Romans appreciated the bird greatly, especially its tongue which was served as an exquisite dish…». -

Habitat Use of the Aesculapian Snake, Zamenis Longissimus, at the Northern Extreme of Its Range in Northwest Bohemia

THE HERPETOLOGICAL BULLETIN The Herpetological Bulletin is produced quarterly and publishes, in English, a range of articles concerned with herpetology. These include society news, full-length papers, new methodologies, natural history notes, book reviews, letters from readers and other items of general herpetological interest. Emphasis is placed on natural history, conservation, captive breeding and husbandry, veterinary and behavioural aspects. Articles reporting the results of experimental research, descriptions of new taxa, or taxonomic revisions should be submitted to The Herpetological Journal (see inside back cover for Editor’s address). Guidelines for Contributing Authors: 1. See the BHS website for a free download of the Bulletin showing Bulletin style. A template is available from the BHS website www.thebhs.org or on request from the Editor. 2. Contributions should be submitted by email or as text files on CD or DVD in Windows® format using standard word-processing software. 3. Articles should be arranged in the following general order: Title Name(s) of authors(s) Address(es) of author(s) (please indicate corresponding author) Abstract (required for all full research articles - should not exceed 10% of total word length) Text acknowledgements References Appendices Footnotes should not be included. 4. Text contributions should be plain formatted with no additional spaces or tabs. It is requested that the References section is formatted following the Bulletin house style (refer to this issue as a guide to style and format). Particular attention should be given to the format of citations within the text and to references. 5. High resolution scanned images (TIFF or JPEG files) are the preferred format for illustrations, although good quality slides, colour and monochrome prints are also acceptable. -

Tail Breakage and Predatory Pressure Upon Two Invasive Snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at Two Islands in the Western Mediterranean

Canadian Journal of Zoology Tail breakage and predatory pressure upon two invasive snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at two islands in the Western Mediterranean Journal: Canadian Journal of Zoology Manuscript ID cjz-2020-0261.R2 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 17-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Febrer-Serra, Maria; University of the Balearic Islands Lassnig, Nil; University of the Balearic Islands Colomar, Victor; Consorci per a la Recuperació de la Fauna de les Illes Balears Draft Sureda Gomila, Antoni; University of the Balearic Islands; Carlos III Health Institute, CIBEROBC Pinya Fernández, Samuel; University of the Balearic Islands, Biology Is your manuscript invited for consideration in a Special Not applicable (regular submission) Issue?: Zamenis scalaris, Hemorrhois hippocrepis, invasive snakes, predatory Keyword: pressure, Balearic Islands, frequency of tail breakage © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 34 Canadian Journal of Zoology 1 Tail breakage and predatory pressure upon two invasive snakes (Serpentes: 2 Colubridae) at two islands in the Western Mediterranean 3 4 M. Febrer-Serra, N. Lassnig, V. Colomar, A. Sureda, S. Pinya* 5 6 M. Febrer-Serra. Interdisciplinary Ecology Group. University of the Balearic Islands, 7 Ctra. Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain. E-mail address: 8 [email protected]. 9 N. Lassnig. Interdisciplinary Ecology Group. University of the Balearic Islands, Ctra. 10 Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain. E-mail address: 11 [email protected]. 12 V. Colomar. Consortium for the RecoveryDraft of Fauna of the Balearic Islands (COFIB). 13 Government of the Balearic Islands, Spain. -

Thése REBBAH Abderraouf Chouaib Bibliothéque.Pdf

République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique Université Larbi Ben M’hidi Oum El Bouaghi Faculté Des Sciences Exactes et des Sciences de la Nature et de la Vie Département des Sciences de la Nature et de la Vie Thèse Présentée en vue de l’obtention du diplôme Doctorat LMD en Sciences de la nature Option: Structure et dynamique des écosystèmes Théme INVENTAIRE ET ECOLOGIE DES OISEAUX FORESTIERS DE DJEBEL SIDI REGHIS (OUM EL BOUAGHI) Présentée par : Mr.REBBAH Abderraouf Chouaib Membres du Jury: Président: BELAIDI Abdelhakim Pr (Université Larbi Ben Mhidi, Oum El-Bouaghi). Promoteur : SAHEBMenouar Pr (Université Larbi Ben Mhidi, Oum El-Bouaghi). Examinateurs: ABABSA Labed Pr (Université Larbi Ben Mhidi, Oum El-Bouaghi). Examinateurs: HOUHAMDI Moussa Pr (Université de Guelma). Examinateurs: OUAKID Mohamed Laid Pr (Université d’Annaba). Année universitaire: 2018-2019 << ِ ِ أَﻟَْﻢ ﺗَ َﺮ أَ ﱠن ﱠاﻪﻠﻟَ ﻳُﺴَﺒِّ ُﺢ ﻟَﻪُ ﻣَ ْﻦ ﻓﻲ اﻟﺴﱠﻤَ َﺎوات َو ْاﻷَ ْر ِض َواﻟﻄﱠْﻴ ُﺮ ٍ ۖ◌ ِ ِ ۗ◌ ِ ِ ﺻَ ﺎ ﻓ ـﱠ ﺎ ت ُﻛ ﻞﱞ ﻗَ ْﺪ ﻋَ ﻠ ﻢَ ﺻَ َﻼ ﺗَ ﻪُ َو ﺗَ ْﺴ ﺒ ﻴ ﺤَ ﻪُ َو ﱠاﻪﻠﻟُ ﻋَﻠﻴﻢٌ ﺑﻤَﺎ ﻳَﻔْ َﻌﻠُ َﻮن >> ﺳﻮرة اﻟﻨﻮراﻷﻳﺔ 41 Dédicaces Je dédie ce travail à : A mes parents qui m’ont tout donné, et qui étaient toujours la à coté de moi dans chaque pats depuis le premier crie pour m’aidé, m’orienté avec leurs amour et leurs sacrifices, malgré les couts dures de la vie. Aucun hommage ne pourrait être à la hauteur de l’amour Dont ils ne cessent de me combler. -

Declive De La Población Más Noroccidental De Chalcides Bedriagai

Bol. Asoc. Herpetol. Esp. (2019) 30(1) 79 Declive de la población más noroccidental de Chalcides bedriagai Pedro Galán Grupo de Investigación en Bioloxía Evolutiva (GIBE). Departamento de Bioloxía. Facultade de Ciencias. Universidade da Coruña. Cam- pus da Zapateira, s/n. 15071 A Coruña. España. C.e.: [email protected] Fecha de aceptación: 10 de junio de 2019. Key words: skinks, lizards, extinction risk, Galicia, threatened populations, wild boar depredation. Chalcides bedriagai es un reptil endémi- Entre los meses de abril y agosto de 2016 co de la península ibérica cuya distribución y 2018 y entre abril y mayo de 2019, se pros- es relativamente amplia dentro de ésta, pectaron las zonas interiores arenosas vegeta- aunque se encuentra ausente de gran parte das de las playas de Lariño y el extremo norte de su tercio norte (Pollo, 2004; Salvador, 2014). de la de Area Maior (Ancoradoiro), espacios En Galicia, donde está el extremo noroc- que constituyen el núcleo principal de esta cidental de su distribución geográfica, las población de eslizón ibérico. Se muestrearon poblaciones son escasas y se encuentran los ecotonos entre las dunas secundarias y los dispersas en su mitad sur (Sociedade Galega de matorrales y herbazales de trasduna. Debi- Historia Natural, 2019), localizándose la más do a que esta especie raramente es observada extrema noroccidental en la costa meridio- activa, la búsqueda se realizó levantando las nal de A Coruña, en las playas de Louro y numerosas piedras que se encuentran sobre Lariño (Galán & Fernández-Arias, 1993; Galán, el suelo arenoso en estas zonas, restos de an- 2003; Serantes & Galán, 2007). -

<I>Salamandra Salamandra</I>

International Journal of Speleology 46 (3) 321-329 Tampa, FL (USA) September 2017 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Subterranean systems provide a suitable overwintering habitat for Salamandra salamandra Monika Balogová1*, Dušan Jelić2, Michaela Kyselová1, and Marcel Uhrin1,3 1Institute of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, P. J. Šafárik University, Šrobárova 2, 041 54 Košice, Slovakia 2Croatian Institute for Biodiversity, Lipovac I., br. 7, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3Department of Forest Protection and Wildlife Management, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences, Kamýcká 1176, 165 21 Praha, Czech Republic Abstract: The fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) has been repeatedly noted to occur in natural and artificial subterranean systems. Despite the obvious connection of this species with underground shelters, their level of dependence and importance to the species is still not fully understood. In this study, we carried out long-term monitoring based on the capture-mark- recapture method in two wintering populations aggregated in extensive underground habitats. Using the POPAN model we found the population size in a natural shelter to be more than twice that of an artificial underground shelter. Survival and recapture probabilities calculated using the Cormack-Jolly-Seber model were very constant over time, with higher survival values in males than in females and juveniles, though in terms of recapture probability, the opposite situation was recorded. In addition, survival probability obtained from Cormack-Jolly-Seber model was higher than survival from POPAN model. The observed bigger population size and the lower recapture rate in the natural cave was probably a reflection of habitat complexity. -

Population Trends of Common Birds in the Italian Alps

Population Index of Common Breeding Birds in Italian Mountain Prairies Rural development: A critical opportunity for people and biodiversity With a spotlight on the Alpine region Turin 6 november 2013 Mountains cover almost a quarter of the Earth surface, host more than 16% of global human population but provide services to many more communities and people Mountains provide many kind of resources that have positive impacts on human health and its prosperity far beyond their natural boundaries. One for all, water The mountains contribute for the 16% to the Italian national GDP However, despite their importance, the conservation status of mountains is not so satisfactory and many problems exist. Some of these are related with human presence and activities, e.g. effects of climate change, pollution, settlement and infrastructures development and tourism pressure; others with the opposite phenomena e.g. changes in cultural landscape and decrease of open habitats, and their biodiversity, due to the land abandonment For these reasons, MITO2000 project (the Italian national common bird monitoring scheme) decided to focus on species breeding in mountain open habitats MITO2000 is part of PECBMS (Pan-European Common Bird Monitoring Scheme), a Europe-wide network of national breeding bird monitoring projects. This network produces indices of population trends of many breeding bird species. One of the most important index is the FBI (Farmland Bird Index), that is one of the EU indicators to assess the impact of agri- environment measures of the CAP These indices are “aggregated indices” because they are calculated averaging the population trends of some species, choosen on the basis of their shared ecological preferences Through objective procedures we identified a group of species breeding in mountain open habitats and, from 2009, we used them to build up a new aggregate index, named FBIpm ( Mountain Prairies Index) Some results .....