<I>Salamandra Salamandra</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-Dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus Spp

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2005 The aN tural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia Michael Steven Osbourn Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Osbourn, Michael Steven, "The aN tural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia" (2005). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 735. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia. Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science Biological Sciences By Michael Steven Osbourn Thomas K. Pauley, Committee Chairperson Daniel K. Evans, PhD Thomas G. Jones, PhD Marshall University May 2005 Abstract The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia. Michael S. Osbourn There are over 4000 documented caves in West Virginia, potentially providing refuge and habitat for a diversity of amphibians and reptiles. Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus porphyriticus, are among the most frequently encountered amphibians in caves. Surveys of 25 caves provided expanded distribution records and insight into ecology and diet of G. -

Maximum Size of the Spectacled Salamander, Salamandrina

©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at 186 SHORT NOTE HERPETOZOA 18 (3/4) Wien, 30. Dezember 2005 SHORT NOTE western Honduras.- Senckenbergiana biologica, ratios than females (e.g., head length/ snout- Frankfurt am Main; 81(1/2): 269-276. MARTINS, M. & vent length, tail length/snout-vent length) as OLIVEIRA, E. (1999): Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus Region, Central Amazonia, Brazil.- reported by VANNI (1980), ZUFFI (1999) and Herpetological Natural History, Phoenix; 6 (2):78-150. ANTONELLI (1999). Total length (TL; i.e. PEREZ-SANTOS, C. & MORENO, A. (1990): Anotaciones from the tip of the snout to the end of the tail) biométricas y alimenticias de la serpiente neotropical of the Spectacled Salamander is usually 8-10 Atractus badius (BOIE, 1827) (Serpentes, Colubridae) de la Colección del Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales cm (VANNI 1980; ZUFFI 1999; ANGELINI et al. de Madrid.- Revista Espanola de Herpetologia, Madrid; 2001). Until 2001 the maximum TL record- 4: 9-15. PETERS, J. A. (1960): The snakes of the sub- ed in males and females were 9.6 cm family Dipsadinae.- Miscellaneous Publications, (ANTONELLI 1999) and 11.6 cm, respectively Museum of Zoology, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor; (114): 1-224. SAVAGE, J. (1960): A revision of the (ZAGAGLIONI 1978; VANNI 1980). Later, Ecuadorian snakes of the colubrid genus Atractus.- ANGELINI et al. (2001) reported a maximum Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology, Univ TL of 12.3 cm recorded in two females from of Michigan, Ann Arbor; (112): 1-86. different populations of S. -

<I>In Vivo</I> Sexual Discrimination in <I>Salamandrina Perspicillata</I

HERPETOLOGICAL JOURNAL 20: 17–24, 2010 In vivo sexual discrimination in Salamandrina perspicillata: a cross-check analysis of annual changes in external cloacal morphology and spermic urine release Leonardo Vignoli1, Romina Silici1, Rossana Brizzi2 & Marco A. Bologna1 1Dipartimento di Biologia Ambientale, Università Roma Tre, Rome, Italy 2Dipartimento di Biologia Evoluzionistica “Leo Pardi”, Università di Firenze, Florence, Italy In Salamandrina, the lack of visible external sexual dimorphism makes the sexing of individuals difficult without sacrifice. The cloaca of Salamandrina in both males and females appears externally as a slit on an unswollen surface, a trait which is consistent throughout the year. Nonetheless, a slight divarication of its borders allows the recognition of three morphs (A, B and C), respectively characterizing male cloaca (all phases), female cloaca without protruding oviductal papillae (courtship phase) and female cloaca with prolapsed oviductal papillae (oviposition phase). Figures and schematic diagrams are provided to illustrate the differences in detail, which are all recognizable to the naked eye or by means of a hand magnifier. In addition to morphology, another reliable method of sexing salamanders is urine examination, albeit only during the courtship and post-courtship phases. Applying these methods for sex determination, we found a male- biased operational sex ratio in two populations, ranging from 6.6:1 (autumn–winter) to 14:1 (May). Males were confined to terrestrial environments, whereas females were also found in water during oviposition. Salamandrina perspicillata was active throughout the year, except during the hottest months (July–August). Key words: cloaca, salamander, sex determination, sex ratio, sexual dimorphism INTRODUCTION Hayes, 1998). Sexing based on behavioural differences requires direct observations, which often prove difficult. -

Is the Italian Stream Frog (Rana Italica Dubois, 1987) an Opportunistic Exploiter of Cave Twilight Zone?

A peer-reviewed open-access journal Subterranean IsBiology the Italian 25: 49–60 stream (2018) frog (Rana italica Dubois, 1987) an opportunistic exploiter... 49 doi: 10.3897/subtbiol.25.23803 SHORT COMMUNICATION Subterranean Published by http://subtbiol.pensoft.net The International Society Biology for Subterranean Biology Is the Italian stream frog (Rana italica Dubois, 1987) an opportunistic exploiter of cave twilight zone? Enrico Lunghi1,2,3, Giacomo Bruni4, Gentile Francesco Ficetola5,6, Raoul Manenti5 1 Universität Trier Fachbereich VI Raum-und Umweltwissenschaften Biogeographie, Universitätsring 15, 54286 Trier, Germany 2 Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università di Firenze, Sezione di Zoologia “La Spe- cola”, Via Romana 17, 50125 Firenze, Italy 3 Natural Oasis, Via di Galceti 141, 59100 Prato, Italy 4 Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Boulevard de la Plaine 2, 1050 Ixelles, Bruxelles, Belgium 5 Department of Environmen- tal Science and Policy, Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Celoria 26, 20133 Milano, Italy 6 Univ. Greno- ble Alpes, CNRS, Laboratoire d’Écologie Alpine (LECA), F-38000 Grenoble, France Corresponding author: Enrico Lunghi ([email protected]) Academic editor: O. Moldovan | Received 22 January 2018 | Accepted 9 March 2018 | Published 20 March 2018 http://zoobank.org/07A81673-E845-4056-B31C-6EADC6CA737C Citation: Lunghi E, Bruni G, Ficetola GF, Manenti R (2018) Is the Italian stream frog (Rana italica Dubois, 1987) an opportunistic exploiter of cave twilight zone? Subterranean Biology 25: 49–60. https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.25.23803 Abstract Studies on frogs exploiting subterranean environments are extremely scarce, as these Amphibians are usually considered accidental in these environments. However, according to recent studies, some anurans actively select subterranean environments on the basis of specific environmental features, and thus are able to inhabit these environments throughout the year. -

The Evolution of Pueriparity Maintains Multiple Paternity in a Polymorphic Viviparous Salamander Lucía Alarcón‑Ríos 1*, Alfredo G

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The evolution of pueriparity maintains multiple paternity in a polymorphic viviparous salamander Lucía Alarcón‑Ríos 1*, Alfredo G. Nicieza 1,2, André Lourenço 3,4 & Guillermo Velo‑Antón 3* The reduction in fecundity associated with the evolution of viviparity may have far‑reaching implications for the ecology, demography, and evolution of populations. The evolution of a polygamous behaviour (e.g. polyandry) may counteract some of the efects underlying a lower fecundity, such as the reduction in genetic diversity. Comparing patterns of multiple paternity between reproductive modes allows us to understand how viviparity accounts for the trade-of between ofspring quality and quantity. We analysed genetic patterns of paternity and ofspring genetic diversity across 42 families from two modes of viviparity in a reproductive polymorphic species, Salamandra salamandra. This species shows an ancestral (larviparity: large clutches of free aquatic larvae), and a derived reproductive mode (pueriparity: smaller clutches of larger terrestrial juveniles). Our results confrm the existence of multiple paternity in pueriparous salamanders. Furthermore, we show the evolution of pueriparity maintains, and even increases, the occurrence of multiple paternity and the number of sires compared to larviparity, though we did not fnd a clear efect on genetic diversity. High incidence of multiple paternity in pueriparous populations might arise as a mechanism to avoid fertilization failures and to ensure reproductive success, and thus has important implications in highly isolated populations with small broods. Te evolution of viviparity entails pronounced changes in individuals’ reproductive biology and behaviour and, by extension, on population dynamics1–3. For example, viviparous species ofen show an increased parental invest- ment compared to oviparous ones because they produce larger and more developed ofspring that are protected from external pressures for longer periods within the mother 4–7. -

Scientific Publications Included in The

Scientific publications included in the SCI Daversa DR, Monsalve-Carcaño C, Carrascal LM, Bosch J, 2018. Seasonal migrations, body temperature fluctuations, and infection dynamics in adult amphibians. PeerJ 6,e4698 Fisher MC, Ghosh P, Shelton JMG, Bates K, Brookes L, Wierzbicki C, Rosa GM, Aanensen DM, Alvarado-Rybak M, Bataille A, Berger L, Böll S, Bosch J, Clare FC, Courtois E, Crottini A, Cunningham AA, Doherty-Bone TM, Gebresenbet F, Gower DJ, Höglund J, Jenkinson TS, Kosch TA, James TY, Lambertini C, Laurila A, Lin CF, Loyau A, Martel A, Meurling S, Miaud C, Minting P, Ndriantsoa S, Pasmans F, Rakotonanahary T, Rabemananjara FCE, Ribeiro LP, Schmeller DS, Schmidt BR, Skerratt L, Smith F, Soto-Azat C, Tessa G, Toledo LF, Valenzuela-Sánchez A, Verster R, Vörös J, Waldman B, Webb RJ, Weldon C, Wombwell E, Zamudio KR, Longcore J, Garner TWJ, 2018. Development and worldwide use of a protocol for the non-lethal isolation of chytrids from amphibians. Scientific Reports 8,7772 O'Hanlon SJ, Rieux A, Farrer RA, Rosa GM, Waldman B, Bataille A, Kosch TA, Murray K, Brankovics B, Fumagalli M, Martin MD, Wales N, Alvarado-Rybak M, Bates KA, Berger L, Böll S, Brookes L, Clare FC, Courtois EA, Cunningham AA, Doherty-Bone TM, Ghosh P, Gower DJ, Hintz WE, Höglund J, Jenkinson TS, Lin CF, Laurila A, Loyau A, Martel A, Meurling S, Miaud C, Minting P, Pasmans F, Schmeller D, Schmidt BR, Shelton JMG, Skerratt LF, Smith F, Soto-Azat C, Spagnoletti M, Tessa G, Toledo LF, Valenzuela-Sánchez A, Verster R, Vörös J, Webb RJ, Wierzbicki C, Wombwell E, Zamudio KR, Aanensen DM, James TY, Gilbert MTP, Weldon C, Bosch J, Balloux F, Garner TWJ, Fisher MC, 2018. -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

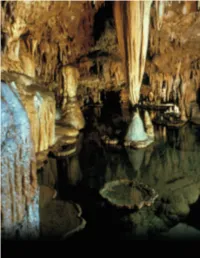

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

Strasbourg, 22 May 2002

Strasbourg, 21 October 2015 T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 [Inf18e_2015.docx] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Standing Committee 35th meeting Strasbourg, 1-4 December 2015 GROUP OF EXPERTS ON THE CONSERVATION OF AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES 1-2 July 2015 Bern, Switzerland - NATIONAL REPORTS - Compilation prepared by the Directorate of Democratic Governance / The reports are being circulated in the form and the languages in which they were received by the Secretariat. This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 - 2 – CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE __________ 1. Armenia / Arménie 2. Austria / Autriche 3. Belgium / Belgique 4. Croatia / Croatie 5. Estonia / Estonie 6. France / France 7. Italy /Italie 8. Latvia / Lettonie 9. Liechtenstein / Liechtenstein 10. Malta / Malte 11. Monaco / Monaco 12. The Netherlands / Pays-Bas 13. Poland / Pologne 14. Slovak Republic /République slovaque 15. “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” / L’« ex-République yougoslave de Macédoine » 16. Ukraine - 3 - T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 ARMENIA / ARMENIE NATIONAL REPORT OF REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA ON NATIONAL ACTIVITIES AND INITIATIVES ON THE CONSERVATION OF AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES GENERAL INFORMATION ON THE COUNTRY AND ITS BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Armenia is a small landlocked mountainous country located in the Southern Caucasus. Forty four percent of the territory of Armenia is a high mountainous area not suitable for inhabitation. The degree of land use is strongly unproportional. The zones under intensive development make 18.2% of the territory of Armenia with concentration of 87.7% of total population. -

Developing Methods to Mitigate Chytridiomycosis, an Emerging Disease of Amphibians

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Developing methods to mitigate chytridiomycosis, an emerging disease of amphibians Geiger, Corina C Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-86534 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Geiger, Corina C. Developing methods to mitigate chytridiomycosis, an emerging disease of amphibians. 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. ❉❡✈❡❧♦♣✐♥❣ ▼❡❤♦❞ ♦ ▼✐✐❣❛❡ ❈❤②✐❞✐♦♠②❝♦✐✱ ❛♥ ❊♠❡❣✐♥❣ ❉✐❡❛❡ ♦❢ ❆♠♣❤✐❜✐❛♥ Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorw¨urde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Universit¨atZ¨urich von Corina Claudia Geiger von Chur GR Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Lukas Keller (Vorsitz) Prof. Dr. Heinz-Ulrich Reyer Dr. Benedikt R. Schmidt (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Matthew C. Fisher (Gutachter) Z¨urich, 2013 ❉❡✈❡❧♦♣✐♥❣ ▼❡❤♦❞ ♦ ▼✐✐❣❛❡ ❈❤②✐❞✐♦♠②❝♦✐✱ ❛♥ ❊♠❡❣✐♥❣ ❉✐❡❛❡ ♦❢ ❆♠♣❤✐❜✐❛♥ Corina Geiger Dissertation Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies University of Zurich Supervisors Dr. Benedikt R. Schmidt Prof. Dr. Heinz-Ulrich Reyer Dr. Matthew C. Fisher Prof. Dr. Lukas Keller Z¨urich, 2013 To all the midwife toads that got sampled during this project ”The least I can do is speak out for those who cannot speak for themselves.” - Jane Goodall Acknowledgements I cordially thank Beni Schmidt for his support which was always so greatly appreciated, be it in fund raising, designing experiments or for his skilled statistical and editorial judgments. He managed to explain the meaning of any complex problem in simple terms and again and again he turned out to be a walking encyclopedia of amphibians, statistical models, Bd and many other common and uncommon topics. -

Salamander Species Listed As Injurious Wildlife Under 50 CFR 16.14 Due to Risk of Salamander Chytrid Fungus Effective January 28, 2016

Salamander Species Listed as Injurious Wildlife Under 50 CFR 16.14 Due to Risk of Salamander Chytrid Fungus Effective January 28, 2016 Effective January 28, 2016, both importation into the United States and interstate transportation between States, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, or any territory or possession of the United States of any live or dead specimen, including parts, of these 20 genera of salamanders are prohibited, except by permit for zoological, educational, medical, or scientific purposes (in accordance with permit conditions) or by Federal agencies without a permit solely for their own use. This action is necessary to protect the interests of wildlife and wildlife resources from the introduction, establishment, and spread of the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans into ecosystems of the United States. The listing includes all species in these 20 genera: Chioglossa, Cynops, Euproctus, Hydromantes, Hynobius, Ichthyosaura, Lissotriton, Neurergus, Notophthalmus, Onychodactylus, Paramesotriton, Plethodon, Pleurodeles, Salamandra, Salamandrella, Salamandrina, Siren, Taricha, Triturus, and Tylototriton The species are: (1) Chioglossa lusitanica (golden striped salamander). (2) Cynops chenggongensis (Chenggong fire-bellied newt). (3) Cynops cyanurus (blue-tailed fire-bellied newt). (4) Cynops ensicauda (sword-tailed newt). (5) Cynops fudingensis (Fuding fire-bellied newt). (6) Cynops glaucus (bluish grey newt, Huilan Rongyuan). (7) Cynops orientalis (Oriental fire belly newt, Oriental fire-bellied newt). (8) Cynops orphicus (no common name). (9) Cynops pyrrhogaster (Japanese newt, Japanese fire-bellied newt). (10) Cynops wolterstorffi (Kunming Lake newt). (11) Euproctus montanus (Corsican brook salamander). (12) Euproctus platycephalus (Sardinian brook salamander). (13) Hydromantes ambrosii (Ambrosi salamander). (14) Hydromantes brunus (limestone salamander). (15) Hydromantes flavus (Mount Albo cave salamander). -

Reproduction and Larval Rearing of Amphibians

Reproduction and Larval Rearing of Amphibians Robert K. Browne and Kevin Zippel Abstract Key Words: amphibian; conservation; hormones; in vitro; larvae; ovulation; reproduction technology; sperm Reproduction technologies for amphibians are increasingly used for the in vitro treatment of ovulation, spermiation, oocytes, eggs, sperm, and larvae. Recent advances in these Introduction reproduction technologies have been driven by (1) difficul- ties with achieving reliable reproduction of threatened spe- “Reproductive success for amphibians requires sper- cies in captive breeding programs, (2) the need for the miation, ovulation, oviposition, fertilization, embryonic efficient reproduction of laboratory model species, and (3) development, and metamorphosis are accomplished” the cost of maintaining increasing numbers of amphibian (Whitaker 2001, p. 285). gene lines for both research and conservation. Many am- phibians are particularly well suited to the use of reproduc- mphibians play roles as keystone species in their tion technologies due to external fertilization and environments; model systems for molecular, devel- development. However, due to limitations in our knowledge Aopmental, and evolutionary biology; and environ- of reproductive mechanisms, it is still necessary to repro- mental sensors of the manifold habitats where they reside. duce many species in captivity by the simulation of natural The worldwide decline in amphibian numbers and the in- reproductive cues. Recent advances in reproduction tech- crease in threatened species have generated demand for the nologies for amphibians include improved hormonal induc- development of a suite of reproduction technologies for tion of oocytes and sperm, storage of sperm and oocytes, these animals (Holt et al. 2003). The reproduction of am- artificial fertilization, and high-density rearing of larvae to phibians in captivity is often unsuccessful, mainly due to metamorphosis. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L.