2020 Artikel Article 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khalladi-Bpp Anexes-Arabic.Pdf

Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 107 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 108 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 109 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 110 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 111 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 112 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 113 The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria are intended to be an easily and widely understood system for classifying species at high risk of global extinction. The IUCN Red List is categorized in the following Categories: • Extinct (EX): A taxon is Extinct when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form. Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects 114 Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 • Extinct in the Wild (EW): A taxon is Extinct in the Wild when it is known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity or as a naturalized population (or populations) well outside the past range. A taxon is presumed Extinct in the Wild when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. -

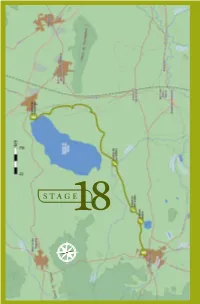

B I R D W a T C H I N G •

18 . F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS STAGE18 E S N O 158 BIRDWATCHING • GR-249 Great Path of Malaga F UENTE DE PIEDRA - CAMPILLOS 18 . STAGE 18 Fuente de Piedra - Campillos L O C A T I O N he José Antonio Valverde Visitor´s Centre at the TReserva Natural de la Laguna de Fuente de Piedra is the starting point of Stage 18. Taking the direction south around the taken up mainly by olive trees and grain. eastern side of the salt water lagoon This type of environment will continue to you will be walking through farmland the end of this stage and it determines until the end of this stage in Campillos the species of birds which can be seen village. The 15, 7 km of Stage 18 will here. You will be crossing a stream and allow you to discover this wetland well then walking along the two lakes which known at national level in Spain, and will make your Stage 18 bird list fill cultivated farmland which creates a up with highly desirable species. The steppe-like environment. combination of wetland and steppe creates very valuable habitats with DESCRIPTION a rare composition of taxa unique at European level. ABOUT THE BIRDLIFE: Stage 18 begins at the northern tip HIGHLIGHTED SPECIES of the lagoon where you take direction Neither the length, diffi culty level or south through agricultural environment, elevation gain of this stage is particularly DID YOU KNOW? ecilio Garcia de la Leña, in Conversation 9th of “Historical Conversations of Malaga” published by Cristóbal Medina Conde (1726-1798) and entitled «About Animal Kingdom of Malaga and some Places in its Bishopric», Ccomments: «…In some lagoons, along sea shores and river banks some large and beautiful birds breed, called Flamingos and Phoenicopteros according to the ancients...», after a description of the bird´s anatomy he adds: «The Romans appreciated the bird greatly, especially its tongue which was served as an exquisite dish…». -

Ship Rats and Island Reptiles: Patterns of Co-Existence in the Mediterranean

Ship rats and island reptiles: patterns of co-existence in the Mediterranean Daniel Escoriza GRECO, University of Girona, Girona, Girona, Spain ABSTRACT Background. The western Mediterranean archipelagos have a rich endemic fauna, which includes five species of reptiles. Most of these archipelagos were colonized since early historic times by anthropochoric fauna, such as ship rats (Rattus rattus). Here, I evaluated the influence of ship rats on the occurrence of island reptiles, including non-endemic species. Methodology. I analysed a presence-absence database encompassing 159 islands (Balearic Islands, Provence Islands, Corso-Sardinian Islands, Tuscan Archipelago, and Galite) using Bayesian-regularized logistic regression. Results. The analysis indicated that ship rats do not influence the occurrence of endemic island reptiles, even on small islands. Moreover, Rattus rattus co-occurred positively with two species of non-endemic reptiles, including a nocturnal gecko, a guild considered particularly vulnerable to predation by rats. Overall, the analyses showed a very different pattern than that documented in other regions of the globe, possibly attributable to a long history of coexistence. Subjects Biodiversity, Biogeography, Conservation Biology, Ecology, Zoology Keywords Alien species, Co-occurrences, Extinction, Island endemic, Lizard INTRODUCTION The Mediterranean basin is a hotspot of biodiversity, but it is also one of the regions Submitted 19 November 2019 Accepted 28 February 2020 in which biodiversity is most threatened, specifically by the massive transformation of Published 19 March 2020 landscapes and the spread of alien species (Médail & Quézel, 1999). The loss of biodiversity Corresponding author in the region began in ancient times, shortly after human colonization of the islands (Vigne, Daniel Escoriza, 1992). -

Tail Breakage and Predatory Pressure Upon Two Invasive Snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at Two Islands in the Western Mediterranean

Canadian Journal of Zoology Tail breakage and predatory pressure upon two invasive snakes (Serpentes: Colubridae) at two islands in the Western Mediterranean Journal: Canadian Journal of Zoology Manuscript ID cjz-2020-0261.R2 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 17-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Febrer-Serra, Maria; University of the Balearic Islands Lassnig, Nil; University of the Balearic Islands Colomar, Victor; Consorci per a la Recuperació de la Fauna de les Illes Balears Draft Sureda Gomila, Antoni; University of the Balearic Islands; Carlos III Health Institute, CIBEROBC Pinya Fernández, Samuel; University of the Balearic Islands, Biology Is your manuscript invited for consideration in a Special Not applicable (regular submission) Issue?: Zamenis scalaris, Hemorrhois hippocrepis, invasive snakes, predatory Keyword: pressure, Balearic Islands, frequency of tail breakage © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 34 Canadian Journal of Zoology 1 Tail breakage and predatory pressure upon two invasive snakes (Serpentes: 2 Colubridae) at two islands in the Western Mediterranean 3 4 M. Febrer-Serra, N. Lassnig, V. Colomar, A. Sureda, S. Pinya* 5 6 M. Febrer-Serra. Interdisciplinary Ecology Group. University of the Balearic Islands, 7 Ctra. Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain. E-mail address: 8 [email protected]. 9 N. Lassnig. Interdisciplinary Ecology Group. University of the Balearic Islands, Ctra. 10 Valldemossa km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain. E-mail address: 11 [email protected]. 12 V. Colomar. Consortium for the RecoveryDraft of Fauna of the Balearic Islands (COFIB). 13 Government of the Balearic Islands, Spain. -

Podarcis Pityusensis, Ibiza Wall Lizard

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T17800A7482971 Podarcis pityusensis, Ibiza Wall Lizard Assessment by: Valentin Pérez-Mellado, Iñigo Martínez-Solano View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Valentin Pérez-Mellado, Iñigo Martínez-Solano. 2009. Podarcis pityusensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009: e.T17800A7482971. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T17800A7482971.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN -

“Italian Immigrants” Flourish on Long Island Russell Burke Associate Professor Department of Biology

“Italian Immigrants” Flourish on Long Island Russell Burke Associate Professor Department of Biology talians have made many important brought ringneck pheasants (Phasianus mentioned by Shakespeare. Also in the contributions to the culture and colchicus) to North America for sport late 1800s naturalists introduced the accomplishments of the United hunting, and pheasants have survived so small Indian mongoose (Herpestes javan- States, and some of these are not gen- well (for example, on Hofstra’s North icus) to the islands of Mauritius, Fiji, erally appreciated. Two of the more Campus) that many people are unaware Hawai’i, and much of the West Indies, Iunderappreciated contributions are that the species originated in China. Of supposedly to control the rat popula- the Italian wall lizards, Podarcis sicula course most of our common agricultural tion. Rats were crop pests, and in most and Podarcis muralis. In the 1960s and species — except for corn, pumpkins, cases the rats were introduced from 1970s, Italian wall lizards were imported and some beans — are non-native. The Europe. Instead of eating lots of rats, the to the United States in large numbers for mongooses ate numerous native ani- the pet trade. These hardy, colorful little mals, endangering many species and lizards are common in their home coun- Annual Patterns causing plenty of extinctions. They also try, and are easily captured in large num- 3.0 90 became carriers of rabies. There are 80 2.5 bers. Enterprising animal dealers bought 70 many more cases of introductions like them at a cut rate in Italy and sold them 2.0 60 these, and at the time the scientific 50 1.5 to pet dealers all over the United States. -

Observations of Marine Swimming in Malpolon Monspessulanus

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 593-596 (2021) (published online on 29 March 2021) Snake overboard! Observations of marine swimming in Malpolon monspessulanus Grégory Deso1,*, Xavier Bonnet2, Cornélius De Haan3, Gilles Garnier4, Nicolas Dubos5, and Jean-Marie Ballouard6 The ability to swim is widespread in snakes and not The diversity of fundamentally terrestrial snake restricted to aquatic (freshwater) or marine species species that colonised islands worldwide, including (Jayne, 1985, 1988). A high tolerance to hypernatremia remote ones (e.g., the Galapagos Archipelago), shows (i.e., high concentration of sodium in the blood) enables that these reptiles repeatedly achieved very long and some semi-aquatic freshwater species to use brackish successful trips across the oceans (Thomas, 1997; and saline habitats. In coastal populations, snakes may Martins and Lillywhite, 2019). However, we do not even forage at sea (Tuniyev et al., 2011; Brischoux and know how snakes reached remote islands. Did they Kornilev, 2014). Terrestrial species, however, are rarely actively swim, merely float at the surface, or were observed in the open sea. While snakes are particularly they transported by drifting rafts? We also ignore the resistant to fasting (Secor and Diamond, 2000), long trips mechanisms that enable terrestrial snakes to survive in the marine environment are metabolically demanding during long periods at sea and how long they can do so. (prolonged locomotor efforts entail substantial energy Terrestrial tortoises travel hundreds of kilometres, can expense) and might be risky (Lillywhite, 2014). float for weeks in ocean currents, and can sometimes Limited freshwater availability might compromise the survive in hostile conditions without food and with hydromineral balance of individuals, even in amphibious limited access to freshwater (Gerlach et al., 2006). -

Podarcis Siculus)

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 21(4):142–143 • DEC 2014 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCED SPECIES FEATURE ARTICLES . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 Notes. The Shared on History of TreeboasTwo (Corallus grenadensisIntroduced) and Humans on Grenada: Populations of A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 theRESEARCH Italian ARTICLES Wall Lizard (Podarcis siculus) . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knighton Anole (Anolis Staten equestris) in Florida Island, New York .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 1,2 3 CONSERVATION ALERTRobert W. Mendyk and John Adragna 1Department of Herpetology,. World’s Mammals Smithsonian in Crisis National............................................................................................................................................................. Zoological Park, 3001 Connecticut Ave NW, Washington, D.C. 20008, USA 220 ([email protected]) -

Contents Herpetological Journal

British Herpetological Society Herpetological Journal Volume 31, Number 3, 2021 Contents Full papers Killing them softly: a review on snake translocation and an Australian case study 118-131 Jari Cornelis, Tom Parkin & Philip W. Bateman Potential distribution of the endemic Short-tailed ground agama Calotes minor (Hardwicke & Gray, 132-141 1827) in drylands of the Indian sub-continent Ashish Kumar Jangid, Gandla Chethan Kumar, Chandra Prakash Singh & Monika Böhm Repeated use of high risk nesting areas in the European whip snake, Hierophis viridiflavus 142-150 Xavier Bonnet, Jean-Marie Ballouard, Gopal Billy & Roger Meek The Herpetological Journal is published quarterly by Reproductive characteristics, diet composition and fat reserves of nose-horned vipers (Vipera 151-161 the British Herpetological Society and is issued free to ammodytes) members. Articles are listed in Current Awareness in Marko Anđelković, Sonja Nikolić & Ljiljana Tomović Biological Sciences, Current Contents, Science Citation Index and Zoological Record. Applications to purchase New evidence for distinctiveness of the island-endemic Príncipe giant tree frog (Arthroleptidae: 162-169 copies and/or for details of membership should be made Leptopelis palmatus) to the Hon. Secretary, British Herpetological Society, The Kyle E. Jaynes, Edward A. Myers, Robert C. Drewes & Rayna C. Bell Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK. Instructions to authors are printed inside the Description of the tadpole of Cruziohyla calcarifer (Boulenger, 1902) (Amphibia, Anura, 170-176 back cover. All contributions should be addressed to the Phyllomedusidae) Scientific Editor. Andrew R. Gray, Konstantin Taupp, Loic Denès, Franziska Elsner-Gearing & David Bewick A new species of Bent-toed gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Cyrtodactylus Gray, 1827) from the Garo 177-196 Hills, Meghalaya State, north-east India, and discussion of morphological variation for C. -

Herpetological Review Volume 38, Number 1 — March 2007

Herpetological Review Volume 38, Number 1 — March 2007 SSAR 50th Anniversary Year SSAR Officers (2007) HERPETOLOGICAL REVIEW President The Quarterly News-Journal of the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles ROY MCDIARMID USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center Editor Managing Editor National Museum of Natural History ROBERT W. HANSEN THOMAS F. TYNING Washington, DC 20560, USA 16333 Deer Path Lane Berkshire Community College Clovis, California 93619-9735, USA 1350 West Street President-elect [email protected] Pittsfield, Massachusetts 01201, USA BRIAN CROTHER [email protected] Department of Biological Sciences Southeastern Louisiana University Associate Editors Hammond, Louisiana 70402, USA ROBERT E. ESPINOZA CHRISTOPHER A. PHILLIPS DEANNA H. OLSON California State University, Northridge Illinois Natural History Survey USDA Forestry Science Lab Secretary MARION R. PREEST ROBERT N. REED MICHAEL S. GRACE R. BRENT THOMAS Joint Science Department USGS Fort Collins Science Center Florida Institute of Technology Emporia State University The Claremont Colleges Claremont, California 91711, USA EMILY N. TAYLOR GUNTHER KÖHLER California Polytechnic State University Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum Senckenberg Treasurer KIRSTEN E. NICHOLSON Section Editors Department of Biology, Brooks 217 Central Michigan University Book Reviews Current Research Current Research Mt. Pleasant, Michigan 48859, USA AARON M. BAUER JOSH HALE MICHELE A. JOHNSON e-mail: [email protected] Department of Biology Department of Sciences Department of Biology Villanova University MuseumVictoria, GPO Box 666 Washington University Publications Secretary Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia Campus Box 1137 BRECK BARTHOLOMEW [email protected] [email protected] St. Louis, Missouri 63130, USA P.O. Box 58517 [email protected] Salt Lake City, Utah 84158, USA Geographic Distribution Geographic Distribution Geographic Distribution e-mail: [email protected] ALAN M. -

Aquatic Habits of Some Scincid and Lacertid Lizards in Italy

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 273-277 (2021) (published online on 01 February 2021) Aquatic habits of some scincid and lacertid lizards in Italy Matteo Riccardo Di Nicola1, Sergio Mezzadri2, Giacomo Bruni3, Andrea Ambrogio4, Alessia Mariacher5,*, and Thomas Zabbia6 Among European lizards, there are no strictly aquatic thermoregulation (Webb, 1980). We here report several or semi-aquatic species (Corti et al., 2011). The only remarkable observations of different behaviours in ones that regularly show familiarity with aquatic aquatic environments in non-accidental circumstances environments are Zootoca vivipara (Jacquin, 1787) and for three Italian lizard species (Chalcides chalcides, especially Z. carniolica (Mayer et al., 2000). Species of Lacerta bilineata, Podarcis muralis). the genus Zootoca can generally be found in wetlands and peat bogs (Bruno, 1986; Corti and Lo Cascio, 1999; Chalcides chalcides (Linnaeus, 1758) Lapini, 2007; Bombi, 2011; Speybroeck, 2016; Di Italian Three-toed Skink Nicola et al., 2019), swimming through the habitat from one floating site to another for feeding, or for escape First event. On 1 July 2020 at 12:11 h (sunny weather; (Bruno, 1986; Glandt, 2001; Speybroeck et al., 2016). Tmax = 32°C; Tavg = 25°C) near Poggioferro, Grosseto These lizards are apparently even capable of diving into Province, Italy (42.6962°N, 11.3693°E, elevation a body of water to reach the bottom in order to flee from 494 m), one of the authors (AM) observed an Italian predators (Bruno, 1986). three-toed skink floating in a near-vertical position in Nonetheless, aquatic habits are considered infrequent a swimming pool, with only its head above the water in other members of the family Lacertidae, including surface (Fig. -

A Case of Limb Regeneration in a Wild Adult Podarcis Lilfordi Lizard

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2017) 41: 1069-1071 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Short Communication doi:10.3906/zoo-1607-53 A case of limb regeneration in a wild adult Podarcis lilfordi lizard 1,2, 1 1,2,3 1 Àlex CORTADA *, Antigoni KALIONTZOPOULOU , Joana MENDES , Miguel A. CARRETERO 1 CIBIO Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, InBIO, University of Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Vila do Conde, Portugal 2 Department of Biology, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal 3 Institute of Evolutionary Biology (CSIC-Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Barcelona, Spain Received: 28.07.2016 Accepted/Published Online: 01.08.2017 Final Version: 21.11.2017 Abstract: We report here a case of spontaneous limb regeneration in a wild Podarcis lilfordi lizard from the Balearic Islands. The animal had lost a hind limb, which regenerated posteriorly into a tail-like appendage. Despite not representing a functional regeneration, the growth of this structure after limb amputation suggests that survival of the individual may have been favored by the less restrictive conditions prevailing in insular environments. Nevertheless, such cases are extremely rare in lizards, with no reported cases over the last 60 years. Key words: Limb regeneration, Podarcis lilfordi, Lacertidae, islands, Balearics Regeneration refers to the ability of an adult organism Lilford’s wall lizard (Podarcis lilfordi) is a lacertid species to restore injured or completely lost tissues and organs endemic to the Balearic Islands. It is currently restricted to (Alibardi, 2010). In reptiles, successful regeneration is the Cabrera archipelago and the offshore islets of Mallorca usually restricted to the replacement of the tail, mainly and Menorca, as it has become extinct in the main islands in lizards that perform tail autotomy (self-amputation) as (Salvador, 2014), likely due to the Neolithic introduction a defensive strategy (Clause and Capaldi, 2006; Alibardi, of allochthonous predators (Pinya and Carretero, 2011).