Japan's Use of Flour Began with Noodles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Muroran Times

people want the most were a branch of the city office and a library, both of them were about MURORAN 19%. Also, the kind of eating places lacking in the area, in order, were family restaurants, soba/udon restaurants, and fast food TIMES establishments. March 1, 2011 No.256 なかじまちょう しょうてんがい じ っ し Muroran City Office 1-2 Saiwai-cho, Muroran, 中島町 の 商店街 で ア ン ケ ー ト を 実施 し た Hokkaido 051-8511JAPAN<0143-22-1111> け っ か ちか ちゅうしゃじょう ひ つ よ う こ え もっと おお 結果、近くに駐車場が必要との声が最も多く News and Topics ありました。 Muroran’s population Muroran Curry Ramen Renewed The Japanese government takes a national Nissin Food Products Co., Ltd renewed census once every 5 years. The most recent one Muroran Curry Ramen, the package type of was held in October 2010. According to the instant noodle and put it on the market. result, the population of Muroran is 94,531. The first Muroran Curry Ramen which was on That is a decrease of 3,841 since the previous the market last March sold two million census. packages around the whole country. At its peak the population of Muroran was 70% of the sales were in Hokkaido, so that the 162,059 in 1970, and it has been decreasing renewed product was put on the market only since then. inside Hokkaido. There are, 179 cities, towns, and villages in Company officials say that the renewed product Hokkaido but only 16 of them have increased in has a spicier taste, and wakame sea weed has population, including Sapporo, Tomakomai. -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

Yeomiji Menu 14

여 미 YEOMIJI 지 Korean BBQ Restaurant APPETIZERS 물만두 Steamed Dumplings 9 두부전 Seared Tofu (v, gf) 8 Steamed homemade dumplings filled with Pan-seared tofu, served with house soy sauce kimchi, tofu, bean sprouts and beef 잡채 Japchae Noodles (v, gf) 15 만두구이 Fried Dumplings 9 Potato glass noodles sautèed with spinich, carrots Pan-fried homemade dumplings filled with and ear mushrooms tofu, zucchini, carrots, mushrooms and glass noodles Choice of beef or vegetarian (v) 떡볶이 Spicy Rice Cakes (v, gf, s) 14 Rice cake sautéed with vegetables in chili sauce 새우 슈마이 Shrimp Shumai 6 Optional addition of hard boiled eggs Steamed miniature wontons filled with shrimp 호박죽 Squash Soup (v, gf) 9 닭날개 Crispy Wings 12 Kabocha squash soup topped with dried dates Battered crispy chicken wings glazed with and pine nuts garlic soy sauce 에다마메 Edamame (v, gf) 6 파전 / 김치, 야채, 해물 Korean Pancakes 13 Baby soy beans steamed and lightly salted Korean pancake with choice of kimchi (v,) (add $2), assorted vegetables (v), or seafood (add $3) SALADS 연어 샐러드 Salmon Salad (gf) 17 아보카도 망고 샐러드 Avocado Mango Salad (v, gf) 15 Mixed greens, salmon sashimi and avocado with Mixed greens, avocado, mango, sun-dried ginger dressing raisins with plum sauce KOREAN TACOS Three palm sized soft corn tortillas with lettuce, scallion, tomato-onion-avocado salsa with choice of topping 갈비 Kalbi 15 닭구이 Chicken 14 소불고기 Beef Bulgogi 14 양념닭 Spicy Chicken (s) 14 돼지불고기 Spicy or Non-Spicy Pork 14 야채 Bean Sprouts and Spinach (v, gf) 13 김치불고기 Kimchi Pork (s) 14 If you have any allergies or dietary restrictions, -

Fukusuke Japanese Ramen

OPEN HOUR LUNCH MON - THU 11:30 AM - 2:00 PM DINNER MON - THU 5:00 PM - 9:00 PM FRI 11:30 AM - 9:30 PM fukusuke SAT & SUN 11:30 AM - 9:00 PM Japanese Ramen Dining Substitution to Kale Noodle / Udon $1 Extra, Cha-Shu can be substituted with Gyoza or RAMEN Steamed Vegetable SHOYU Shoyu ... SOY SAUCE FLAVOR SHOYU RAMEN 9.79 2 pcs Chashu Pork, Naruto, Bamboo Shoots, Black Mushroom, Seaweed & Green Onion MISO Spicy Miso CHASHUMEN 11.29 5 pcs Chashu Pork, Naruto, Bamboo Shoots, Black Mushroom, Seaweed & Green Onion MISO RAMEN 11.29 2 pcs Chashu Pork, Naruto, Bamboo Shoots, SUPER CHASHUMEN RAMEN 13.79 Black Mushroom, Corn & Green Onion 8pcs Chashu Pork, Naruto, Soft/Hard Boiled Egg, Green Onion & Roasted Garlic Oil SPICY MISO 11.79 2 pcs Chashu Pork, Naruto, Bamboo Shoots, MOYASHI SHOYU RAMEN 11.99 Black Mushroom, Corn, Green Onion, Caramelized Chopped Chashu Pork, Bean Sprout, Jalapeno & Spicy Red Miso Green Onion, Red Onion, Roasted Seaweed MOYASHI MISO RAMEN 12.99 SHOYU RAMEN W/ CHICKEN KARAAGE 11.79 Caramelized Chopped Chashu Pork, Bean Sprout, Deep Fried Chicken Breast, Naruto, Roasted Seaweed, Green Onion, Red Onion & Corn Soft/Hard Boiled Egg & Green Onion SPICY “GARLIC BUTTER CORN” 11.79 3 pcs Chashu Pork, Garlic Butter Corn, Green Onion, Jalapeno & Spicy Red Miso TENNO SEAFOOD RAMEN 14.29 2 pcs Jumbo Shrimps, 2 pcs Mussels, Langostinos, Red Onion, Jalapeno, Cilantro, Green Onion, Bean Sprout, Yuzu Lemon & Spicy Red Miso Super Chashumen SHIO ... SEA SALT FLAVOR SHIO RAMEN 9.79 2 pcs Chashu Pork, Naruto, Bamboo Shoots, Black Mushroom -

Yaki Udon Noodles

DINNER MENU APPETIZERS SALADS Edamame / 4.00 Pork Gyoza / 5.50 House Salad / 3.50 Pork Eggroll / 5.50 Cucumber Sunomono / 4.95 Fried Vegetarian Spring Roll / 5.50 Seaweed Salad / 4.95 Crab Rangoon / 6.50 Squid Salad / 5.95 Calamari Tempura / 8.95 Spicy Sashimi Salad / 14.95 Shrimp Tempura / 8.95 Vegetable Tempura / 6.95 FRIED RICE *No Egg Upon Request* Vegetable Fried Rice / 9.95 Steak Fried Rice / 12.95 Tofu Fried Rice / 10.95 Shrimp Fried Rice / 12.95 Chicken Fried Rice / 11.95 Combo Fried Rice / 13.95 (Chicken, Steak, and Shrimp) NOODLES Choose between thin wheat yakisoba noodles or thick yaki udon noodles Vegetable Yakisoba or Yaki Udon / 10.95 Chicken Yakisoba or Yaki Udon / 12.95 Tofu Yakisoba or Yaki Udon / 11.95 Steak Yakisoba or Yaki Udon / 13.95 Shrimp Yakisoba or Yaki Udon / 13.95 Combo Yakisoba or Yaki Udon / 14.95 (Chicken, Steak, and Shrimp) HOUSE SPECIALS Tempura Udon / 13.95 Thick, wheat noodle in a refreshingly mild-flavored soy dashi broth. Dol-Sot-Bop Served with / tempura 14.95 shrimp and veggies Steamed rice with sauteed beef and vegetables topped with a fried egg and served in a hot stone bowl. Bul-Dak / 16.95 Spicy Korean-style fire chicken and sauteed veggies. Served with steamed rice Tofu Dol-Sot-Bop / 13.95 Steamed rice with tofu and vegetables topped with a fried egg and Bulgogi served / 17.95 in a hot stone bowl Korean-style barbeque beef and sauteed vegetables. Served with steamed rice ENTREES Served with miso soup, house salad, vegetables, and steamed rice (Substitute fried rice for $2.50) Spicy Ginger Shrimp / Blackened Tuna Steak / 18.95 17.95 Chicken Katsu / Pineapple Chicken Karaage / (breaded in panko and deep fried) (Sweet and sour) 18.95 19.95 Teriyaki Chicken / Hibachi Steak / 18.95 20.95 S I D E S Steamed Rice / 2.50 Sauteed Vegetables / 7.95 Miso Soup / 3.00 Steamed Vegetales / 7.95 Sushi Rice / 3.50 DESSERTS Tempura Ice Cream / Mochi Ice Cream / Green Tea Ice Cream / 6.00 5.00 4.00 . -

MD-Document-5Ce3908b-F876-4D68

ABOUT KIYOSHI, JAPANESE RESTAURANT Kiyoshi,清 which is used in the main icon of the restaurant’s logo is known asきよし in Japanese. True to its name, Kiyoshi’s main focus is to provide a light and wholesome meal for customers. Kiyoshi prides itself on fresh ingredients prepared using an innovative, contemporary approach. The restaurant specialises in inaniwa udon, a type of udon made in the Inaniwa area of Inakawa machi, Akita prefecture. Other highlights of Kiyoshi include sashimi, sushi, nabemono (Japanese hotpot), donburi, sake, tsukemen, yakitori and affordably priced bento sets. 01 COLD INANIWA UDON CU-1 Kiyoshi Japanese Restaurant is one of the few Japanese restaurants in Singapore specialising in inaniwa udon, a type of udon made in the Inaniwa area of Inakawa machi, Akita prefecture. This cream coloured udon is hand-stretched and is slightly thinner than regular udon, yet thicker than sōmen, or hiyamugi noodles. The most important part of the making process is the repeated hand-kneading technique which helps it to achieve its thin, smooth and delicate, melt-in-your mouth texture. The production of Inaniwa udon requires meticulous selection of ingredients and human effort, so they cannot be made in large quantities. Inaniwa udon used to be a delicacy for the privileged, however thanks to modern production techniques, it can now be enjoyed by everyone. CU-1 Kiyoshi Combination Udon $38.80 CU-3 Gyu Onsen Udon $22.80 3 kinds of udon in a set Cold thin udon with sukiyaki beef, king oyster mushroom and softboiled egg CU-2 Tempura Zaru Udon $23.80 Cold thin udon with side of mixed CU-4 Ten Chirashi Udon $23.80 tempura Cold thin udon with deep fried scallop, mushroom, avocado & cherry tomato CU-2 CU-4 Additional $2 for soba or cha soba All images are for illustration purpose only. -

Mooncat Ramen

MoonCat Ramen Menu Appetizer Edamame 3.5 Edamame Spicy 4 Shishitou(Green pepper) 5 Chashu 5 Takoyaki 6 Ikageso 6 Pork Gyoza (5pc) 6 Vegetarian Gyoza (5pc) 6 Kurobuta sausages 7 Chicken Karage 5 Ton-katsu (Pork katsu) 7.5 Chicken katsu 7 Buns 4 Bao -Chicken 5 -Chashu 5 Kaki-fry 7.5 Table side fry 7 Palla di riso 3 -6pc small rice ball (Enjoy with Ramen or Carpaccio! ) Onigiri (2pc) 4 Miso soup 3 Seaweed salad 6.5 Small green salad 4 Arizona Salad 9 Seasoned Spinach Ohitashi 3 Carpaccio -Salmon 6 Add Palla di riso -Tuna 7 (Rice-ball) for any salads -Urchin ※ASK +2 Ramen The Tonkotsu broth is prepared in the restaurant by hand. Please note that there may be slight differences in the consistency of the broth from day-to-day. Tonkotsu Ramen 12.5 Rich pork based broth with roasted pork, bean sprouts, boiled egg, green onion, red ginger Monrovia Tonkotsu Ramen 8 Original soup of MoonCat with roasted pork, boiled egg, green onion, red ginger Miso Ramen 12 Soybean paste broth with roasted pork, spinach, boiled egg, green onion, corn Shoyu Ramen 9.5 Soy sauce based clear broth with roasted pork, spinach, boiled egg, green onion, bamboo shoots Toppings for all Ramen Happy Shoyu Jr. 5 Green onion, red ginger, Small Shoyu ramen spinach, corn, bamboo shoots, bean sprouts, Yuzu-shio Ramen 10 nori(seaweed) +1 Japanese citrus and salt clear broth with roasted pork, Boiled egg +1.5 spinach, boiled egg, green onion, bamboo shoots Extra noodles +2 Curry Ramen 11 Japanese curry over Shoyu Ramen Pork belly, ground beef, (Chicken curry, Potato, Carrot, Onion) -

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

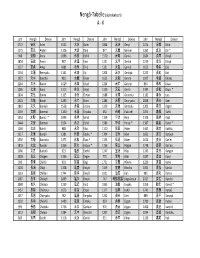

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Tonkotsu Ramen with Kakuni Chashu $8.95 Spicy Miso Yaki

Tonkotsu Ramen with Kakuni Chashu $8.95 Upgrade to DOUBLE CHASHU +$4 Rich pork bone broth with ramen noodles. Topped with Kakuni Chashu, boiled egg, chopped green onions and red bell peppers, and a dash of sesame seeds. Served with crunchy garlic oil on the side. Spicy Miso Yaki Udon $8.95 Zero Spicy Super Krazy +$0 +$0 +$0.25 +$0.50 Select Spiciness Thick udon noodles stir-fried in our special spicy miso sauce. Includes sliced mushrooms, onions, broccoli, shredded cabbage, chopped red bell peppers and green onions. Topped with bonito flakes and a dash of sesame seeds. Chicken Katsu with Spicy Tartar Sauce $7.95 A crispy fried chicken cutlet topped with spicy tartar sauce with chopped boiled eggs. Serve on a bed of spicy shredded cabbage salad. BBQ Beef Sushi Roll $9.45 Grilled Bistro Hanger Steak in Miso marinade rolled up with mixed greens, red bell peppers, and mayo. Wrapped with white rice and nori seaweed. Served with hot & spicy sauce on the side. Fried Chicken Karaage Sushi Roll $8.45 Fried Chicken Karaage rolled up with cucumbers, red bell peppers, and wasabi mayo. Wrapped with white rice and nori seaweed. Served with a dab of wasabi on the side. Gyu-Kaku Mochi-Boba with Brown Sugar Milk *Contains soybeans and dairy *Please ask a server for availability $6.75 Delicious chewy mochi with Kuromitsu, a Japanese brown sugar syrup, and milk on ice is a sweet and refreshing treat! Only at participating Gyu-Kaku Japanese BBQ locations. Item and pricing may vary by location. Other restrictions may apply. -

The Ichikawa and Warrior Family Dynamics In

ALPINE SAMURAI: THE ICHIKAWA AND WARRIOR FAMILY DYNAMICS IN EARLY MEDIEVAL JAPAN by KEVIN L. GOUGE A THESIS Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2009 ii “Alpine Samurai: The Ichikawa and Warrior Family Dynamics in Early Medieval Japan,” a thesis prepared by Kevin L. Gouge in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of History. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Goble, Chair of the Examining Committee ________________________________________ Date Committee in Charge: Dr. Andrew Goble, Chair Dr. Jeffrey Hanes Dr. Peggy Pascoe Accepted by: ____________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School iii © 2009 Kevin L. Gouge iv An Abstract of the Thesis of Kevin L. Gouge for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History to be taken June 2009 Title: ALPINE SAMURAI: THE ICHIKAWA AND WARRIOR FAMILY DYNAMICS IN EARLY MEDIEVAL JAPAN Approved: _______________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Goble This study traces the property lineage of the Ichikawa family of Japan’s Shinano province from the early 1200s through the mid-1300s. The property portfolio originated in complicated inheritance dynamics in the Nakano family, into which Ichikawa Morifusa was adopted around 1270. It is evident that Morifusa, family head for the next fifty years, was instrumental in establishing a solid foundation for the Ichikawa’s emergence as a powerful warrior clan by 1350. This study will begin with a broad interpretation of the concept of warrior “family” as reflected in a variety of primary sources, followed by an in-depth case study of six generations of the Nakano/Ichikawa lineage. -

COOKING Ready-Made Store-Bought Noodles

COOKING Ready-Made Store-Bought Noodles Semi-fresh han nama men 半生麺・乾麺 Dried kan men・冷凍麺 frozen reitō men When I don’t have the time (or a group of people to help me stomp, roll and cut noodle dough) to make fresh-stomped udon, my personal preference is to purchase han nama udon or semi-fresh udon noodles. Han-nama udon are easily available in stores throughout Japan. However, when buying Japanese noodles overseas. kan men or “dried noodles” are usually a more reliable choice. Many brands will have Sanuki 讃岐 as part of their name; this refers to the Sanuki region of Shikoku (current day Kagawa prefecture) known for its udon. Ishimaru brand (logo above) produces many excellent kinds of Sanuki-style udon noodles; two dried kan men products I have used while in the U.S.A. are té uchi hōchō-giri (”knife cut”) noodles and regular Sanuki udon noodles. Pictured below, left to right: regular DRIED Sanuki-style udon, DRIED té uchi hōchō-giri Sanuki-style udon, SEMI-FRESH Sanuki-style udon. Store all dried and shelf-stable noodles as you would any pasta, on a cool, dark, dry shelf. After opening the original packages, transfer remaining contents to a lidded jar, canister, or sealed bag (include the packet of drying agent that came with the original package). Label the container with the date the package was opened; it is best to use the product within a few months, though spoilage is rare even a year later. Cooking times for packaged Japanese noodles vary enormously according to the type (dried kan men or semi-dried han nama), and from brand to brand.