The Ichikawa and Warrior Family Dynamics In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No.723 (April Issue)

NBTHK SWORD JOURNAL ISSUE NUMBER 723 April, 2017 Meito Kansho Examination of Important Swords Juyo Bijutsu Hin Important Art Object Type: Tachi Owner: Mori Kinen (memorial) Shu-sui Museum Mei: Toshitsune Length: 2 shaku 3 sun1 bu 8 rin (70.25 cm) Sori: 9 bu 6 rin (2.9 cm) Motohaba: 9 bu 2 rin (2.8 cm) Sakihaba: 6 bu 3 rin (1.9 cm) Motokasane: 2 bu (0.6 cm) Sakikasane: 1 bu 1 rin (0.35 cm) Kissaki length: 8 bu 6 rin (2.6 cm) Nakago length: 6 sun 5 bu 7 rin (19.9 cm) Nakago sori: 1 bu (0.3 rin) Commentary This is a shinogi zukuri tachi with an ihorimune, a standard width, and there is not much difference in the widths at the moto and saki. It is slightly thick, there is a large koshi-sori with funbari, the tip has a prominent sori, and there is a short chu- kissaki. The jihada is itame mixed with mokume, the entire jihada is well forged, and some areas have a fine ko-itame jihada. There are ji-nie, chikei along the itame hada areas, and jifu utsuri. The entire hamon is high, and composed of ko- gunome mixed with ko-choji, square gunome, and togariba. The hamon’s vertical alterations are not prominent, and in some places it is a suguha type hamon. There are ashi and yo, a nioiguchi, a little bit of uneven fine mura, and mizukaze-like utsuri at the koshimoto is very clear and almost looks like a hamon. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90w6w5wz Author Carter, Caleb Swift Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Caleb Swift Carter 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries by Caleb Swift Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor William M. Bodiford, Chair This dissertation considers two intersecting aspects of premodern Japanese religions: the development of mountain-based religious systems and the formation of numinous sites. The first aspect focuses in particular on the historical emergence of a mountain religious school in Japan known as Shugendō. While previous scholarship often categorizes Shugendō as a form of folk religion, this designation tends to situate the school in overly broad terms that neglect its historical and regional stages of formation. In contrast, this project examines Shugendō through the investigation of a single site. Through a close reading of textual, epigraphical, and visual sources from Mt. Togakushi (in present-day Nagano Ken), I trace the development of Shugendō and other religious trends from roughly the thirteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. This study further differs from previous research insofar as it analyzes Shugendō as a concrete system of practices, doctrines, members, institutions, and identities. -

The Dogen Canon D 6 G E N ,S Fre-Shobogenzo Writings and the Question of Change in His Later Works

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1997 24/1-2 The Dogen Canon D 6 g e n ,s Fre-Shobogenzo Writings and the Question of Change in His Later Works Steven H eine Recent scholarship has focused on the question of whether, and to what extent, Dogen underwent a significant change in thought and attitudes in nis Later years. Two main theories have emerged which agree that there was a decisive change although they disagree about its timing and meaning. One view, which I refer to as the Decline Theory, argues that Dogen entered into a prolonged period of deterioration after he moved from Kyoto to Echizen in 1243 and became increasingly strident in his attacks on rival lineages. The second view, which I refer to as the Renewal Theory, maintains that Dogen had a spiritual rebirth after returning from a trip to Kamakura in 1248 and emphasized the priority of karmic causality. Both theories, however, tend to ignore or misrepresent the early writings and their relation to the late period. I will propose an alternative Three Periods Theory suggesting that the main change, which occurred with the opening of Daibutsu-ji/Eihei-ji in 1245, was a matter of altering the style of instruc tion rather than the content of ideology. At that point, Dogen shifted from the informal lectures (jishu) of the Shdbdgenzd,which he stopped deliver ing, to the formal sermons (jodo) in the Eihei koroku, a crucial later text which the other theories overlook. I will also point out that the diversity in literary production as well as the complexity and ambiguity of historical events makes it problematic for the Decline and Renewal theories to con struct a view that Dogen had a single, decisive break with his previous writings. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Nihontō Compendium

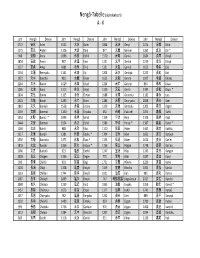

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

BEYOND THINKING a Guide to Zen Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK Spiritual practice is not some kind of striving to produce enlightenment, but an expression of the enlightenment already inherent in all things: Such is the Zen teaching of Dogen Zenji (1200–1253) whose profound writings have been studied and revered for more than seven hundred years, influencing practitioners far beyond his native Japan and the Soto school he is credited with founding. In focusing on Dogen’s most practical words of instruction and encouragement for Zen students, this new collection highlights the timelessness of his teaching and shows it to be as applicable to anyone today as it was in the great teacher’s own time. Selections include Dogen’s famous meditation instructions; his advice on the practice of zazen, or sitting meditation; guidelines for community life; and some of his most inspirational talks. Also included are a bibliography and an extensive glossary. DOGEN (1200–1253) is known as the founder of the Japanese Soto Zen sect. Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. Translators Reb Anderson Edward Brown Norman Fischer Blanche Hartman Taigen Dan Leighton Alan Senauke Kazuaki Tanahashi Katherine Thanas Mel Weitsman Dan Welch Michael Wenger Contributing Translator Philip Whalen BEYOND THINKING A Guide to Zen Meditation Zen Master Dogen Edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi Introduction by Norman Fischer SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2012 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Japan's Use of Flour Began with Noodles

By Hiroshi Ito, Japan’s Use of Flour Began with Noodles owner of Nagaura in Ginza Noodles Introduced by Zen Priests In previous issues of FOOD CULTURE, Hirotaka Matsumoto described the globalization of sushi with stories and photos from his own travels to sushi restaurants and stores in thirty-five cities in twenty-five countries. He provided detailed reports of the tremendous expansion of sushi throughout the world, indicating that there are 14,000 to 18,000 restaurants and stores selling sushi around the world. In the course of its history, the foods and diet of Japan have assimilated aspects of the food cultures of many coun- tries. More than any other, the use of flour, introduced from China during the Middle Ages (end of the twelfth cen- tury to the end of the sixteenth century) took firm root in Japan, making noodles a food with an importance comparable to rice, the staple food of the Japanese diet. In this issue, we begin to trace the historical development of noodles, focusing on the flour processing techniques brought from China by Japanese Zen priests, and the process that made noodles a major Japanese food. Zen Buddhism, and Dogen (1200–1253), founder of the Soto Introduction school of Zen. Seeking to revitalize Buddhism in Japan at a Since ancient times, the Japanese have included the grains fox- time when it had become quite stagnant, the priests crossed the tail millet (Setaria italica), millet (Panicum miliaceum) and sea to Zhejiang province in Jiangnan (region to the south of rice in their diet. The Japanese diet underwent three major the Yangtze river) in China. -

Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation Carl Bielefeldt

cover next page > title: Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation author: Bielefeldt, Carl. publisher: University of California Press isbn10 | asin: 0520068351 print isbn13: 9780520068353 ebook isbn13: 9780585111933 language: English subject Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. publication date: 1988 lcc: BQ9449.D657B53 1988eb ddc: 294.3/443 subject: Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i This volume is sponsored by the Center for Japanese Studies University of California, Berkeley < previous page page_i next page > cover next page > title: Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation author: Bielefeldt, Carl. publisher: University of California Press isbn10 | asin: 0520068351 print isbn13: 9780520068353 ebook isbn13: 9780585111933 language: English subject Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. publication date: 1988 lcc: BQ9449.D657B53 1988eb ddc: 294.3/443 subject: Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. cover next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation Carl Bielefeldt University of California Press Berkeley, Los Angeles, London < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv To Yanagida Seizan University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1988 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bielefeldt, Carl. Dogen's manuals of Zen meditation Carl Bielefeldt. p. cm. Bibliography: p. ISBN 0-520-06835-1 (ppk.) 1. Dogen, 1200-1253. -

Vocalizing the Lament Over the Buddha's Passing

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 43/1: 89–130 © 2016 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture http://dx.doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.43.1.2016.89-130 Michaela Mross Vocalizing the Lament over the Buddha’s Passing A Study of Myōe’s Shiza kōshiki This article examines the Shiza kōshiki (Kōshiki in four sessions), composed by the Kegon-Shingon monk Myōe (1173–1232) for the Nehan’e (Assembly on the Buddha’s nirvana). It analyzes the performance practice of the Shiza kōshiki at Myōe’s temple Kōzanji during his lifetime and at Shingon temples in the Tokugawa period, paying special attention to its musical dimension. During the Nehan’e, clerics sang various liturgical pieces of different styles and thus created a rich sonic landscape. The musical method of reciting a kōshiki text further helped effectively convey its content and thereby supported the devo- tional function of the kōshiki. At certain occasions, singing was also a means to actively engage lay attendees in the ritual. In this way, I demonstrate that music is an essential element in kōshiki, as well as in Buddhist rituals in general. An annotated translation of the Nehan kōshiki, the first of the Shiza kōshiki’s four kōshiki, is included in the online supplement to this JJRS issue. keywords: Myōe—kōshiki—shōmyō—Śākyamuni—ritual—nenbutsu—Nehan’e Michaela Mross is Shinjō Itō Postdoctoral Fellow for Japanese Buddhism at the Univer- sity of California, Berkeley. 89 n contemporary Japan the most famous observance of a kōshiki 講式 is the Shiza kōshiki (Kōshiki in four sessions), which is performed annually dur- ing the Jōrakue 常楽会, the commemoration of the death of the Buddha, at IKongōbuji 金剛峰寺 on Kōyasan. -

Encyclopedia of Japanese History

An Encyclopedia of Japanese History compiled by Chris Spackman Copyright Notice Copyright © 2002-2004 Chris Spackman and contributors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” Table of Contents Frontmatter........................................................... ......................................5 Abe Family (Mikawa) – Azukizaka, Battle of (1564)..................................11 Baba Family – Buzen Province............................................... ..................37 Chang Tso-lin – Currency............................................... ..........................45 Daido Masashige – Dutch Learning..........................................................75 Echigo Province – Etō Shinpei................................................................ ..78 Feminism – Fuwa Mitsuharu................................................... ..................83 Gamō Hideyuki – Gyoki................................................. ...........................88 Habu Yoshiharu – Hyūga Province............................................... ............99 Ibaraki Castle – Izu Province..................................................................118 Japan Communist Party – Jurakutei Castle............................................135