Chartbook on Women's Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Report Covers Updates to Cleveland

Master Plan Update Report City of Cleveland Heights Page 1 11 47 159 Vision Goal Action Overall Summary % Status Pending 6.92 On Track 59.75 Some Disruption 1.89 Status 47% Major Disruption 1.26 Progress Upcoming 0.63 0 100 Completed 29.56 Report Legend No Update Overdue # Priority Page 2 Plan Summary Vision 1 Progress 56% Vision 2 Progress 56% % # % # On Track 70.83 17 Status Pending 4.76 1 Some Disruption 8.33 2 On Track 42.86 9 Status Completed 20.83 5 Status Upcoming 4.76 1 Completed 47.62 10 Vibrant Neighborhoods Cleveland Heights will be a city of strong, Complete Transportation Network Cleveland Heights will be a safe, and vibrant neighborhoods composed of a variety of community where getting to work, meeting friends over dinner, or beautiful homes and buildings, well-maintained yards and shopping can be accomplished easily by foot, bike, transit, or car greenspaces, historic districts, active neighborhood associations, along beautiful and well-maintained streets that safely and and revitalized blocks. comfortably accommodate all users. Vision 3 Progress 55% Vision 4 Progress 55% % # % # Status Pending 7.14 1 On Track 60.0 9 On Track 35.71 5 Completed 40.0 6 Status Some Disruption 7.14 1 Status Major Disruption 14.29 2 Completed 35.71 5 Environmentally Sustainable Community Cleveland Heights will Business Friendly Cleveland Heights will be a business-friendly be an environmentally sustainable community that uses green community that leverages the city’s entrepreneurial spirit, well- infrastructure to capture and slow stormwater, encourages active educated population, solid services, strong infrastructure, and transportation, and promotes state of the art building techniques proximity to world-class institutions to foster new businesses, to preserve the environment. -

NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress

Institute of Education Sciences U.S. Department of Education NCES 2009–479 NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress READING 1971–2008 MATHEMATICS 1973–2008 CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Executive Summary 6 Introduction This report presents the results of the NAEP long- 8 The Long-Term Trend Assessment term trend assessments in reading and mathemat- in Reading ics, which were most recently given in the 2007–08 28 The Long-Term Trend Assessment school year to students at ages 9, 13, and 17. Nationally representative samples of over 26,000 in Mathematics public and private school students were assessed 50 Technical Notes in each subject area. 53 Appendix Tables The long-term trend assessments make it possible to chart educational progress since the early 1970s. Results in reading are available for 12 assessments going back to the rst in 1971. The rst of 11 assess- ments in mathematics was administered in 1973. What is Throughout this report, the most recent results are compared to those from 2004 and from the rst year The Nation’s the assessment was conducted. ™ Report Card ? The original assessment format, content, and proce- dures were revised somewhat in 2004 to update content The Nation’s Report Card™ informs the public about and provide accommodations to students with disabili- the academacademicic achachievementievement ooff elementarelementaryy and ties and English language learners. The knowledge and secondary students in the United StatesStates. Report skills assessed, however, remain essentially the same cards communicate the findings of the National since the rst assessment year. Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a continuing and nationally representative measure Improvements seen in reading and of achievement in various subjects over time. -

Developing Achievement Levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress for Writing Grades 8 and 12 in 2011 and Grade 4 in 2013

National Assessment Governing Board Developing Achievement Levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress for Writing Grades 8 and 12 in 2011 and Grade 4 in 2013 Submitted to: Dr. Susan Loomis National Assessment Governing Board 800 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 825 Washington, DC 20002-4233 Email: [email protected] Phone: 202.357.6940 This study was funded by the National Assessment Governing Board under Contract ED-NAG-10-C-0003. Submitted by: Measured Progress 100 Education Way Dover, NH 03820 Phone: 603.749.9102 NAEP Writing ALS Design Document March 10, 2011 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 Purpose of This Document ................................................................................. 5 Organization of This Document ......................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 7 Body of Work ...................................................................................................... 7 BoW Technological Integration and Enhancements (BoWTIE) ..................... 10 Research Studies ..................................................................................................... 13 Field Trial .......................................................................................................... 13 Hardware .................................................................................................... -

Part 2 Almaz, Salyut, And

Part 2 Almaz/Salyut/Mir largely concerned with assembly in 12, 1964, Chelomei called upon his Part 2 Earth orbit of a vehicle for circumlu- staff to develop a military station for Almaz, Salyut, nar flight, but also described a small two to three cosmonauts, with a station made up of independently design life of 1 to 2 years. They and Mir launched modules. Three cosmo- designed an integrated system: a nauts were to reach the station single-launch space station dubbed aboard a manned transport spacecraft Almaz (“diamond”) and a Transport called Siber (or Sever) (“north”), Logistics Spacecraft (Russian 2.1 Overview shown in figure 2-2. They would acronym TKS) for reaching it (see live in a habitation module and section 3.3). Chelomei’s three-stage Figure 2-1 is a space station family observe Earth from a “science- Proton booster would launch them tree depicting the evolutionary package” module. Korolev’s Vostok both. Almaz was to be equipped relationships described in this rocket (a converted ICBM) was with a crew capsule, radar remote- section. tapped to launch both Siber and the sensing apparatus for imaging the station modules. In 1965, Korolev Earth’s surface, cameras, two reentry 2.1.1 Early Concepts (1903, proposed a 90-ton space station to be capsules for returning data to Earth, 1962) launched by the N-1 rocket. It was and an antiaircraft cannon to defend to have had a docking module with against American attack.5 An ports for four Soyuz spacecraft.2, 3 interdepartmental commission The space station concept is very old approved the system in 1967. -

Table of Artificial Satellites Launched in 1989

This electronic version (PDF) was scanned by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an original paper document in the ITU Library & Archives collections. La présente version électronique (PDF) a été numérisée par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'un document papier original des collections de ce service. Esta versión electrónica (PDF) ha sido escaneada por el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un documento impreso original de las colecciones del Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la UIT. (ITU) ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﻓﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺃﺟﺮﺍﻩ ﺍﻟﻀﻮﺋﻲ ﺑﺎﻟﻤﺴﺢ ﺗﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﻧﺘﺎﺝ (PDF) ﺍﻹﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﻫﺬﻩ .ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﻮﻓﺮﺓ ﺍﻟﻮﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﺿﻤﻦ ﺃﺻﻠﻴﺔ ﻭﺭﻗﻴﺔ ﻭﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﻣﻦ ﻧﻘﻼ ً◌ 此电子版(PDF版本)由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案室利用存于该处的纸质文件扫描提供。 Настоящий электронный вариант (PDF) был подготовлен в библиотечно-архивной службе Международного союза электросвязи путем сканирования исходного документа в бумажной форме из библиотечно-архивной службы МСЭ. © International Telecommunication Union Settling in. Traveling a t2 3 /0 0 0 miles perhour, Europe’s In less than a decade, Europe’s ambitious manned orbiter Hermes will auickly leave agenda in space is scheduled to become a the coast of Somalia in its wake. And head reality. Alcatel Espace looks forward to work into the sixteenth sunset of the day. ing with the European Space Agency, and Just over the horizon, a rendezvous awaits. partners like NASA ana CNES, to make the The Columbus Attached Module, an inhabit process of settling in a little easier. ed scientific platform moored to America’s Our contribution? Earth-to-orbit transmis Space Station, prepares for a link-up. -

Module 3 Slide Handouts

Pathways of Progress™ Module 3: The Logic Behind Pathways of Progress TM Three Guiding Principles in Establishing Pathways of Progress Matter Individual Student Learning Goals • We know that the level of skills for a student at the Meaningful. beginning of the year is an important predictor of their – Goals should support students to achieve meaningful outcomes or increase the likelihood of achieving meaningful and important end of year outcome (partial eta squared = 71%). outcomes. • Pathways of Progress contributes to initial skills in Ambitious. predicting later outcomes (partial eta squared = 17%). – Above typical or well above typical progress are ambitious goals. – Typical progress may be sufficient for students who are at or above benchmark – Typical progress may not be adequate for students who are likely to need additional support to achieve benchmark goals. – Below typical or well below typical progress are just not very ambitious. Attainable. – High in the well above typical range is probably not attainable. – Typical and above typical progress is readily attainable. – Well below typical and below typical progress may be attainable, but are not ambitious or meaningful. Pathways of ProgressTM ©2015 Dynamic Measurement Group 33 Pathways of ProgressTM ©2015 Dynamic Measurement Group 34 Considerations in Establishing Considerations in Establishing Student Learning Goals Student Learning Goals DIBELS Next informed considerations: Other considerations: What rate of progress is above typical progress What rate of progress is possible with a very compared to other students with similar initial skills? effective, research based intervention? What rate of progress is necessary to narrow the What resources are available to support instruction achievement gap with students making adequate and intervention? progress? What is the student attendance pattern? What rate of progress is necessary to achieve important benchmark goals. -

Mir Hardware Heritage Index

Mir Hardware Heritage Index A attitude control systems (continued) on Kvant 2 165 Aktiv docking unit. See docking systems: Aktiv on Mir 106, 119, 123, 131, 137 Almaz (see also military space stations) on Original Soyuz 157, 168-169, 187 hardware adaptation to Salyut 69, 71 on Salyut 1 67 history 63-65 on Salyut 6 75, 79, 81, 84-85 missions 177-178 on Salyut 7 91, 100, 185 in station evolution 1, 62, 154-156 on Soyuz 1 10 system tests 70 on Soyuz Ferry 24-25 Almaz 1 64, 65, 68, 177 on Soyuz-T 47, 50 Almaz 1V satellite 65 on space station modules 155 on TKS vehicles 159 Almaz 2 64, 65, 68, 73, 177, 178 on Zond 4 14 Almaz 3 64, 73, 178 Almaz 4 64 Altair/SR satellites B description 105 berthing ports 76, 103, 105, 165 illustration 106 BTSVK computer 47 missions 108, 109, 113, 115, 118, 121, 133, 139 Buran shuttle androgynous peripheral assembly system (APAS). See crews 51, 54, 98 docking systems: APAS-75; APAS-89 flights 115, 188, 193 Antares mission 136 hardware adapted to Polyus 168 APAS. See docking systems: APAS-75; APAS-89 illustration 189 Apollo program (U.S.) (see also Apollo Soyuz Test and Mir 107, 167 Project) and Salyut 7 161 command and service module (CSM) 5, 6, 16, 172, 173, 176, 177 illustration 176 C lunar module (LM) 19, 21, 172 circumlunar flight 3, 4, 5, 12, 63, 155, 173, 175 (see illustration 175 also lunar programs) missions 172, 173, 175-178 Cosmos 133 10, 171 Apollo Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) (see also ASTP Soyuz) Cosmos 140 10, 172 background 6, 65 Cosmos 146 14, 172 mission 28, 34-35, 177-178 Cosmos 154 14, 172 and Soyuz 18 72 Cosmos 186 10-11, 172 approach systems. -

Maarten Doorman

artinprogress2.def 20-10-2003 11:58 Pagina 1 Maarten Doorman Art is supposed to be of our time or rather to be part of Art in Progress the future. This perspective has reigned the arts and art criticism for more than a century. The author of this challenging and erudite essay shows how the idea of progress in the arts came up A Philosophical Response to the End of the Avant-Garde and he describes the enormous retorical impact of progressive concepts. After the end of the avant-garde the idea of progress in the arts collapsed and soon philosophers like Arthur Danto Doorman Maarten proclaimed the end of art. Doorman investigates the crippling effects of postmodernism on the arts and proposes a new form of progress to understand contemporary art. Its history can still be seen as a process of accumulation: works of art comment on each other, enriching each other’s meanings. These complex interrelationships lead to progress in both the sensibility of the observer and the significance of the works of art. Art in Progress Maarten Doorman is an In the nineteenth century, the history of painting associate professor of was regarded as the paradigm of a progressive under- philosophy at the taking, and evidence that historical progress is a University of Maastricht possible ideal everywhere else. In post-modernist and a professor of literary times, however, progress seems to have all but lost criticism at the University meaning against prevailing philosophies of the end of Amsterdam. The Dutch of art. But the end of art does not entail that there has edition of this title was not been genuine progress in the philosophy of art. -

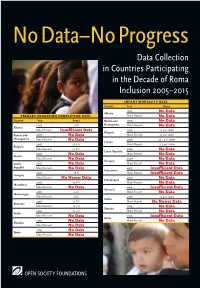

No Data No Progress

No Data–No Progress Data Collection in Countries Participating in the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005–2015 INFANT MORTALITY RATE Country Year Roma 2005 No Data Albania PRIMARY EDUCATION COMPLETION RATE Most Recent No Data Country Year Roma Bosnia and 2005 No Data 2005 14% Herzegovina Most Recent No Data Albania Most Recent Insuffi cient Data 2005 25 per 1000 Bulgaria Bosnia and 2005 No Data Most Recent 25 per 1000 Herzegovina Most Recent No Data 2005 25.1 per 1000 Croatia 2005 28.3% Most Recent 11.5 per 1000 Bulgaria Most Recent 31.6% 2005 No Data Czech Republic 2005 No Data Most Recent No Data Croatia Most Recent No Data 2005 No Data Hungary Czech 2005 No Data Most Recent No Data Republic Most Recent No Data 2005 Insuffi cient Data Macedonia 2005 76% Most Recent Insuffi cient Data Hungary Most Recent No Newer Data 2005 No Data Montenegro 2005 50.8% Most Recent No Data Macedonia Most Recent No Data 2005 Insuffi cient Data Romania 2005 9.2% Most Recent No Data Montenegro Most Recent 20% 2005 25 per 1000 Serbia 2005 31.7% Most Recent No Newer Data Romania Most Recent 19.7% 2005 No Data Slovakia 2005 22.7% Most Recent No Data Serbia Most Recent No Data 2005 Insuffi cient Data Spain 2005 No Data Most Recent No Data Slovakia Most Recent No Data 2005 No Data Spain Most Recent No Data OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS No Data—No Progress Data Collection in Countries Participating in the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005–2015 No Data—No Progress Data Collection in Countries Participating in the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005–2015 June 2010 Roma Initiatives OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS Copyright © 2010 by the Open Society Institute. -

Crop Progress - State Stories

Crop Progress - State Stories ISSN: 2470-9816 Released March 31, 2020, by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). ALABAMA: Average temperatures ranged from 2.4 to 14.5 degrees warmer than historical values. Total rainfall for the month ranged from trace amounts of rain to 11.1 inches in Limestone County. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, the State remained drought free throughout the month. Most of the State was affected by heavy rains throughout the month, delaying field preparations for many. In areas where rain slowed down later in the month, corn was planted, cotton and peanut fields had lime and fertilizer applied, and hay was being chemically burned for the new hay season. Herbicide and fertilizer applications for wheat were delayed due to excessive rain and flooding throughout the month. Some wheat fields were still under water, but starting to recover. The wheat crop was rated in fair to excellent condition, overall. Pastures were greening, but not fast enough for cattlemen that were at the end of their hay supplies and needing relief. However, cattle were still in good condition. Vegetable planting had begun and the strawberry crop was looking good. ALASKA: DATA NOT AVAILABLE ARIZONA: This report for Arizona is for the week ending Sunday, March 29, 2020. By the end of this week, 98 percent of Durum wheat has emerged, according to the Mountain Regional Field Office of the National Agricultural Statistics Service, USDA. Thirty-five percent has headed compared with 22 percent last year. Durum wheat conditions were rated mostly excellent. -

Quarterly Progress Report

Quarterly Progress Report Award Information Title Award # Awardee Smart City Challenge DTFH6116H00013 City of Columbus Demonstration Report Information Date Submitted Submitted To Period Covered by Report May 18, 2017 Kate Hartman January 2017 - March 2017 Project Scope Scope Statement Implementation of the Smart Columbus Smart City Demonstration consisting of 15 projects spread across 2 enabling Technologies and 4 Districts: 1. Columbus Connected Transportation Network (CCTN) 1. Connected Vehicle Environment 2. Smart Street Lighting 3. Transit Pedestrian Collision Avoidance System 2. Integrated Data Exchange (IDE) 4. IDE 3. Residential District 5. Common Payment System 6. Multi-Modal Trip Planning Application 7. Smart Mobility Hubs 8. Mobility Assistance for People with Cognitive Disabilities 4. Commercial District 9. Connected Electric Automated Vehicles 5. Downtown District 10. Delivery Zone Availability 11. Enhanced Permit Parking 12. Event Parking Management 6. Logistics District 13. Truck Platooning 14. Oversize Vehicle Routing 15. Interstate Truck Parking Availability 1 Financial Status Task Financial Summary (See Note 1) Note 1: After last quarter’s report we agreed the City’s labor cost would all stay within Program Management. Task 3 was to be broken down by its two components and Task 4 was to be broken down by its four components. We are still working on breaking task 3 and 4 into the components and anticipate reporting expenses that way on the next quarterly report. Costs Incurred vs Budgeted Costs Costs Incurred vs Obligated Federal Funding Direct Labor Hours Worked (See Note 2) 2 Note 2: Some hours were estimated on the last quarterly report. There are no estimated hours on this report. -

Interim Progress Report

INTERIM PROGRESS REPORT Period covered by report: 1 August 2012 to 31 July 2013 Proposal Title: (MURI) Value-centered Information Theory for Adaptive Learning, Inference, Tracking, and Exploitation Contract/Grant #: W911NF-11-1-0391 Authors of report: Alfred O. Hero (PI), U of Michigan Douglas Cochran, Arizona State U Emre Ertin, Ohio State U John W. Fisher III, MIT Jonathon How, MIT Michael Jordan, UC Berkeley Randolph L. Moses, Ohio State U Raj Rao Nadakuditi, U of Michigan Stefano Soatto, UCLA Alan Willsky, MIT Angela Yu, UCSD ARO proposal number: W911NF-11-1-0391 Principal Investigator: Alfred O. Hero, Professor Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science The University of Michigan 1301 Beal Ave Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2122 Tel: 734 763 0564 Email: [email protected] Submitted to: Dr. Liyi Dai Program Manager Army Research Office Raleigh, NC MURI: Value-centered Information Theory Year 2 IPR Abstract This interdisciplinary project is developing a comprehensive set of principles for task-specific information extraction and information exploitation that can be used to design the next gen- eration of autonomous and adaptive sensing systems. The significance of this research is that it addresses the widespread and longstanding problem of defining, assessing, and exploiting the value of information in active sensing systems. This year we report progress in twenty areas organized around three main thrusts: (1) learning and representation of high dimensional data, (2) distributed information fusion, and (3) active information exploitation. In the learning and representation thrust, progress ranges from assessing value of Kronecker representations of high-dimensional covariance matrices to learning to rank user preference data, an impor- tant task for human-in-the-loop decision systems.