VISIBLE LANGUAGE the J Ournal for Research on the Visual Media of Language Expression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studia Muzealne Zeszyt Xxii / 2017 Muzealne Zeszyt Studia

MUZEUM NARODOWE W POZNANIU • ZESZYT XXII • 2017 ROK ISBN 978-83-64080-11-1 ISSN 0137-5318 STUDIA MUZEALNE ZESZYT XXII / 2017 MUZEALNE ZESZYT STUDIA ZESZYT XXII POZNAŃ 2017 Redakcja: Wojciech Suchocki, Adam Soćko Sekretarz redakcji: Agnieszka Skalska Autorzy: Inga Głuszek, Maria Gołąb, Tadeusz I. Grabski, Paweł Ignaczak, Kamila Kłudkiewicz, Tadeusz Wojciech Lange, Jakub Mosiejczyk, Agnieszka Patała, Juliusz Raczkowski, Danuta Rościszewska Recenzenci: Mariusz Bryl, Piotr Juszkiewicz, Adam Labuda Tłumaczenie streszczeń na język angielski: Marcin Turski Redakcja wydawnicza: Magdalena Knapowska Projekt graficzny: Ewa Wąsowska Skład i przygotowanie do druku: Lucyna Majchrzak Opracowanie materiału ilustracyjnego: Tomasz Niziołek Kierownictwo produkcji: Urszula Namiota Fotografie: Adam Cieślawski, Jakub Baszczyński (Pracownia Fotografii Cyfrowej MNP), Katarzyna Giesz- czyńska-Nowacka, Tadeusz I. Grabski, Monika Jakubek-Raczkowska, Kamila Kłudkiewicz, Agnieszka Patała, Marek Peda, Arkadiusz Podstawka, Juliusz Raczkowski; Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu, Одесский художественный музей w Odessie, Thorvaldsens Museum w Kopenhadze, www.zabytki.ocalicodzapomnienia.eu Zgoda na zamieszczenie fotografii: Monika Jakubek-Raczkowska, Kamila Kłudkiewicz, Agnieszka Patała, Juliusz Raczkowski, Fundacja im. Raczyńskich przy Muzeum Narodowym w Poznaniu, Kościół św. Micha- ła Archanioła w Osetnie, Kościół św. Bartłomieja w Nowogrodzie Bobrzańskim, Kościół pw. Matki Bożej Bolesnej w Dzikowicach, Kościół św. Katarzyny w Gościszowicach, Kościół św. Mikołaja w Mycielinie, Kościół św. Marii Magdaleny w Nowym Miasteczku, Kościół św. Wawrzyńca w Babimoście, Musée de l’oeuvre de Notre-Dame, Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu, Одесский художественный музей w Odessie, Thorvaldsens Museum w Kopenhadze Druk: Zakład Poligraficzny Moś i Łuczak Sp.j., Poznań Dział Handlowy Muzeum Narodowego w Poznaniu, Aleje Marcinkowskiego 9, 61-745 Poznań, tel. -

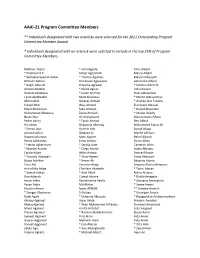

AAAI-21 Program Committee Members

AAAI-21 Program Committee Members ** Individuals designated with two asterisks were selected for the 2021 Outstanding Program Committee Member Award. * Individuals designated with an asterisk were selected to include in the top 25% of Program Committee Members. Mathieu ’Aquin * John Agosta Chris Alberti * Prathosh A P Forest Agostinelli Marco Alberti * Sathyanarayanan Aakur * Thomas Agotnes Marjan Albooyeh Mohsen Abbasi Don Joven Agravante Alexandre Albore * Ralph Abboud Priyanka Agrawal * Stefano Albrecht Ahmed Abdelali * Derek Aguiar Vidal Alcazar Ibrahim Abdelaziz * Julien Ah-Pine Huib Aldewereld Tarek Abdelzaher Ranit Aharonov * Martin Aleksandrov Afshin Abdi Sheeraz Ahmad * Andrea Aler Tubella S Asad Abdi Wasi Ahmad Francesco Alesiani Majid Abdolshah Saba Ahmadi * Daniel Alexander Mohammad Abdulaziz Zahra Ahmadi * Modar Alfadly Naoki Abe Ali Ahmadvand Gianvincenzo Alfano Pedro Abreu * Faruk Ahmed Ron Alford Rui Abreu Shqiponja Ahmetaj Mohammed Eunus Ali * Erman Acar Hyemin Ahn Daniel Aliaga Avinash Achar Qingyao Ai Malihe Alikhani Rupam Acharyya Marc Aiguier Rahaf Aljundi Panos Achlioptas Esma Aimeur Oznur Alkan * Hanno Ackermann * Sandip Aine Cameron Allen * Maribel Acosta * Diego Aineto Adam Allevato Carole Adam Akiko Aizawa Amine Allouah * Sravanti Addepalli * Nirav Ajmeri Faisal Almutairi Bijaya Adhikari * Kenan Ak Eduardo Alonso Yossi Adi Yasunori Akagi Amparo Alonso-Betanzos Aniruddha Adiga Charilaos Akasiadis * Tansu Alpcan * Somak Aditya * Alan Akbik Mario Alviano Don Adjeroh Cuneyt Akcora * Daichi Amagata Aaron Adler Ramakrishna -

Mise En Page 2

LivretRDC221210.qxd 8/01/11 15:01 Page 1 PROGRAMME CASQUETTES VERTES RD CONGO • Biodiversité • Bonobos • Développement durable • Bikelamo binso • Bonobos • Bokolisi mboka bokoumela Apprendre avec les Casquettes vertes Koyekola elöngö na ba Casquettes vertes Programme soutenu par : Awely, des animaux et des hommes 12 place du Chatelet - 45000 Orléans - France / www.awely.org - [email protected] ONG de statut associatif Loi 1901 - Siret : 484 353 610 00039 ACTION LivretRDC221210.qxd 8/01/11 15:01 Page 3 PROGRAMME CASQUETTES VERTES RD CONGO LivretRDC221210.qxd 8/01/11 15:01 Page 5 table des COMMENÇONS PAR UNE HISTOIRE… 4 - 7 TOBANDELA NA MWA LISOLO... LA BIODIVERSITÉ C’EST QUOI ? 8 - 11 BIKELAMO BINSÖ NDE BANANI ? En tant que Casquette verte d’Awely, Bo Casquette verte ya Awely, nazali matières MIEUX CONNAÎTRE LA FORÊT CONGOLAISE 12 - 17 MALAMU KOBEYA ZAMBA YA CONGO je suis heureux de te présenter na esengo ya bopesi yo buku eye, lokasa la MIEUX CONNAÎTRE LES BONOBOS 18 - 25 MALAMU KOYEBA BABONOBO ce livret dans lequel tu trouveras plein oyo okokuta bansango ebele oyo itali mateya LES CONSÉQUENCES DE LA CHASSE 26 - 27 MAMBI MABE MAKOUTAKA NA BOKILA d’informations sur ton environnement. etando ya mokili na yö. LE DÉVELOPPEMENT DURABLE, 28 - 33 BOKOLISI MBOKA BOKOUMELA, Amuse toi bien ! Misakana malamu ! UN BIEN POUR TOUS BOLAMU BWA BATO BANSO COMMENT VOUS IMPLIQUER ? 34 - 35 NDENGE NINI OKOKI KOMIPESA ? LivretRDC221210.qxd 8/01/11 15:01 Page 7 COMMENÇONS PAR UNE HISTOIRE COMMENÇONS PAR UNE HISTOIRE - TOBANDELA NA MWA LISOLO TOBANDELA NA MWA LISOLO Lobi eleki Tango na kala, bato bazalaki kobika na Lelo boyokani bolamu kati na bango na zamba na Aujourd’hui bango. -

Summer Preschool Funded Programs

Summer Preschool Funded Programs The following programs were awarded Summer Preschool Funds on June 4, 2021. The list is alphabetized by city name, and sites are also included in Early Childhood Longitudinal Data Systems (ECLDS) Comprehensive Services Map. Use this list and the Summer Preschool Map to support families in the community with eligible children find and enroll in a program. View the Minnesota Department of Education (MDE) Early Learning Programs webpage for more information about Summer Preschool Funding. Program Summer Preschool Summer Preschool Summer Preschool Program Name Address City ZIP Code Type Contact Name Contact Email Contact Phone Littlelearnersadamn CHILD CARE Little Learners,LLC 201 9th st w suite 3 Ada 56510 Karen DeVos 218-474-1254 @outlook.com DISTRICT AITKIN PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT 306 2nd St NW Aitkin 56431-1289 Julie Miller [email protected] 218-927-7730 cnovak@district745. DISTRICT ALBANY PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT 30 Forest Ave Albany 56307-0040 Cassandra Novak 320-845-5072 org ALBERT LEA PUBLIC SCHOOL jennifer.hanson@alsc DISTRICT 211 W Richway Dr Albert Lea 56007-2477 Jenny Hanson 5073794832 DISTRICT hools.org Cherie Osmundson/Little Rascals hockeydad3@charter CHILD CARE 2305 Margaretha Ave Albert Lea 56007 Cherie Osmundson 507-377-9202 Daycare .net [email protected] CHILD CARE Kozy Kidz Daycare 915 Lincoln Ave Albert Lea 56007 Lisa Olson 507-369-3563 om srregister@alchildren CHILD CARE The Children's Center 801 Luther Place Albert Lea 56007 Samantha Register 507-373-7979 scenter.org srregister@alchildren CHILD CARE The Children's Center 605 James Ave Albert Lea 56007 Samantha Register 507-373-7979 scenter.org ALEXANDRIA PUBLIC SCHOOL aelarson@alexschool DISTRICT 1410 McKay Ave S Ste 201 Alexandria 56308-2493 April Larson 3207623305 DISTRICT s.org [email protected] CHILD CARE Alisha Hoekstra Family Childcare 1804 Kari St NE Alexandria 56308 Alisha Hoekstra 3207606005 m butterflyhillnaturepr CHILD CARE Butterfly Hill Nature Preschool 2210 6th Ave. -

Università Degli Studi Di Milano

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO Dipartimento di Lingue e Letterature Straniere Dottorato di Ricerca in Studi Linguistici, Letterari e Interculturali in Ambito Europeo ed Extraeuropeo XXXI° Ciclo Toy stories: comfort toys e modelli di comportamento nella children’s literature dal 1800 alla contemporaneità SSD L/LIN-10 — Letteratura inglese Tesi di Dottorato di: BEATRICE MOJA R11278 Tutor: Prof.ssa Francesca Orestano Coordinatore del Dottorato: Prof.ssa Maria Vittoria Calvi Anno Accademico 2017-2018 Abstract Toy stories: comfort toys and models of behaviour in the children’s literature from 1800 to the contemporaneity This dissertation focuses on the characterization and role of toys in English language children’s literature, with an emphasis on differences and similarities in the cultural contexts where toys play a primary role. Although regarded as material objects, toys are depositaries of values and deep connotations attributed to them by human society. Through the critical perspectives offered by material culture studies, thing theory, psychology, and cultural memory, the present work highlights the role of toys in the dynamics of identity building, leading to specific responses to the social context, and choices in gender roles. The analysis proposed in this work is divided into two parts. The first part coincides with the first chapter, “Toys, material culture, and literature”, which makes reference to a critical bibliography that draws on the field of children’s literature, childhood studies, but also a series of theories and cultural methodologies which offer meaningful suggestions on the nature of toys, their use, and their application. The second part of the present work analyses a selected corpus of texts, which refer to different chronological-geographical areas and literary genres, using them as models where the theories discussed find an immediate practical application. -

The Daily Egyptian, December 09, 1980

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC December 1980 Daily Egyptian 1980 12-9-1980 The aiD ly Egyptian, December 09, 1980 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_December1980 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, December 09, 1980." (Dec 1980). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1980 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in December 1980 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iran leader expects en£1 Vaily ~gyptian to captivity Southern Illinois Unin:rsity lh ThP ·\ssociatfod J>r"" Tht• speaker of lran·s ~Mrharnent saorl Monday the l nJted States harl come "much closer · to rne..tmg demands for relea~e of lht• American hostal(f•S .:Jnd he lhmks the !J ~;:~nth-Hld cns1s "will be ~H Hashem• HafsanJani tokl a ne""" conierence 1n Tehran tht• latt•st 1· S response to Iran" four condltmn.-. flJr release ol the .;2 hosldges ht•ld for 13 moolhs ·has come rnoch doser '" "olnng tt:e problem · · "11 tht• l'mted States mt"eb our demands. and 1: seems th<~t ; II tht·y want to. the problem -'Ill tw settl•-d." hl' "'lid "In th<> past tht> l'nit£.; States ~li's <HTt>ptt>d our d.-mands on I·• pnnc1plf' hut th1s time i' has I_· takt·n rnore dear steps tn ~Xt'<'utmg them · · !{.:Jfsanjani also ruled out a !urther study of the rnatter bv the :\laJIIs. the !raman . -~ parh:.rnf'nt. -

Long-Term Group Membership and Dynamics in a Wild Western Lowland Gorilla Population (Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla) Inferred Using Non-Invasive Genetics

Received: 21 March 2018 | Revised: 22 June 2018 | Accepted: 1 July 2018 DOI: 10.1002/ajp.22898 RESEARCH ARTICLE Long-term group membership and dynamics in a wild western lowland gorilla population (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) inferred using non-invasive genetics Laura Hagemann | Christophe Boesch | Martha M. Robbins | Mimi Arandjelovic | Tobias Deschner | Matthew Lewis* | Graden Froese† | Linda Vigilant Department of Primatology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, The social organization of a group-living animal is defined by a balance between Leipzig, Germany group dynamic events such as group formation, group dissolution, and dispersal Correspondence events and group stability in membership and over time. Understanding these Laura Hagemann, Department of Primatology, processes, which are relevant for questions ranging from disease transmission Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Deutscher Platz 6, 04103 patterns to the evolution of polygyny, requires long-term monitoring of multiple Leipzig, Germany. social units over time. Because all great ape species are long-lived and elusive, the Email: [email protected] number of studies on these key aspects of social organization are limited, especially Funding information for western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). In this study, we used non- Max Planck Society; Tusk Trust; Berggorilla 2 und Regenwald Direkthilfe e. V.; United invasive genetic samples collected within an approximately 100 km area of Loango States Fish and Wildlife Service Great Ape National Park, Gabon to reconstruct group compositions and changes in Conservation Fund composition over more than a decade. We identified 98 gorillas and 11 mixed sex groups sampled during 2014–2017. Using published data from 85 individuals and 12 groups surveyed between 2005 and 2009 at the same locality, we tracked groups and individuals back in time. -

Annual Report 2016 Sequencing for a Better Life

sequencing for a better life annual report 2016 cnag centre nacional d’anàlisi genòmica centro nacional de análisis genómico 01 02 03 director 2016 in facts research highlights • director’s report • single cell genomics operation at • foreword by the CRG director CNAG–CRG • the genome of the Iberian lynx • the IHEC coordinated paper release • accuracy and speed of germline variant calling pipelines • should network biology be used for drug discovery? • the genetic history of Aboriginal Australians • decoding the complete genome os the olive tree • ancient admixture between chimpanzees and bonobos 04 05 06 platform overview research programmes appendix • sequencing unit • bioinformatic development & • funding • bioinformatics unit statistical genomics • collaborators • genome assembly and • human resources annotation • projects • biomedical genomics • publications • population genomics • structural genomics • comparative genomics • single cell genomics annual report 2016 01. director director’s report foreword by the CRG director 2016 has been another productive and successful year for CNAG- complete epigenetic descriptions of cells of the immune system and CRG. We have continued our strategic path to offer the best put them in context of different diseases. They also describe tools 02. 2016 in facts possible support to our collaborators in their research projects. that were developed to capture the entire content of epigenetic Of particular focus are areas of patient-near research, such as in profiles. CNAG-CRG played a key role in this effort by sequencing 03. research highlights rare diseases and cancer. From an applications points of view we and analysing nearly 200 whole genome methylomes. single cell genomics operation at CNAG–CRG have extended our expertise in single cell analysis, epigenomics, the genome of the Iberian lynx translational techniques and the integration of population The RD-Connect database that was developed at the CNAG-CRG the IHEC coordinated paper release information. -

FALCON V, LLC, Et Al., DEBTORS. CHAPTER 11

Case 19-10547 Doc 275 Filed 07/03/19 Entered 07/03/19 14:06:14 Page 1 of 1 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA IN RE: CHAPTER 11 FALCON V, L.L.C., et al.,1 CASE NO. 19-10547 DEBTORS. JOINTLY ADMINISTERED CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE Attached hereto is the Affidavit of Service of Winnie Yeung of Donlin, Recano & Company, Inc. (the “Affidavit”) which declares that a copy of the Notice to Holders of Claims Against Debtor of the Bar Dates for Filing Proofs of Claim and Proof of Claim and Instructions was served on the parties listed in Exhibit 3 to the Affidavit on July 3, 2019. Dated: July 3, 2019 Respectfully submitted, KELLY HART PITRE /s/ Rick M. Shelby Patrick (Rick) M. Shelby (#31963) Louis M. Phillips (#10505) Amelia L. Bueche (#36817) One American Place 301 Main Street, Suite 1600 Baton Rouge, LA 70801-1916 Telephone: (225) 381-9643 Facsimile: (225) 336-9763 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Debtors 1 The “Debtors” are the following entities (the corresponding bankruptcy case numbers follow in parentheses): Falcon V, L.L.C. (Case No. 19-10547), ORX Resources, L.L.C. (Case No. 19-10548), and Falcon V Holdings, L.L.C. (Case No. 19-10561). The address of the Debtors is 400 Poydras Street, Suite 1100, New Orleans, Louisiana 70130. 1 Case 19-10547 Doc 275-1 Filed 07/03/19 Entered 07/03/19 14:06:14 Page 1 of 295 Case 19-10547 Doc 275-1 Filed 07/03/19 Entered 07/03/19 14:06:14 Page 2 of 295 . -

A Malay-English Vocabulary Containing 6500 Malay Words Or

T^p r /$*jc(i*^e^r Ji . ^uJcl/^£>% ^ :$ &+ g^jl* & e#£wj S^Mea^Js M .% •* ^liffi^a^^NKHiiiiwiiiN)^ THE CELLAR BCCK SHCP 18090 WYOMING DETROIT, MICH. 48221 U.S.A. Malay=English Vocabulary Containing ft 5 00 Malay Words or Phrases with their English equivalents, together with AN APPENDIX Of Household, Nautical and Medical Terms, etc., etc. , <* BY REV. wf U. SHELLABEAR, Missionary of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Author of "A Practical Malay (Jraimnar," etc., etc. SINGAPORE: I'll- IXTKI) \NI> I*UIIMK1I.KJ> HY THK AmKIIH'AN MISSION PliKSS. 1902. ,5 54- i$6X £jt yjio -u/ PREFACE. This Vocabulary has been prepared for use in connection with my * 'Practical Malay Grammar." It was originally intended to incorpor- ate with the Grammar an English-Malay and a Malay-English Voca- bulary, each containing some three or four thousand words, but in view of the fact that most people require a vocabulary containing as large a number of words as possible and are subjected to much "dis- appointment and annoyance when they find that their vocabulary does not contain just the very words which they require, it has been thought better to publish the vocabularies separately and to make them as complete as is consistent with the low price at which such works are expected to sell. The list of words which is here offered to the public contains over six thousand words and phrases. In such a Jist it is of course impos- sible to include all the Malay words which may be met with in even a very limited range of Malay reading, and the student will no doubt- meet with some expressions in conversation with Malays which will not be found in this vocabulary. -

Squandering Paradise?

THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS SQUANDERING PARADISE? The importance and vulnerability of the world’s protected areas By Christine Carey, Nigel Dudley and Sue Stolton Published May 2000 By WWF-World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund) International, Gland, Switzerland Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above- mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © 2000, WWF - World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund) ® WWF Registered Trademark WWF's mission is to stop the degradation of the planet's natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by: · conserving the world's biological diversity · ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable · promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption Front cover photograph © Edward Parker, UK The photograph is of fire damage to a forest in the National Park near Andapa in Madagascar Cover design Helen Miller, HMD, UK 1 THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS Preface It would seem to be stating the obvious to say that protected areas are supposed to protect. When we hear about the establishment of a new national park or nature reserve we conservationists breathe a sigh of relief and assume that the biological and cultural values of another area are now secured. Unfortunately, this is not necessarily true. Protected areas that appear in government statistics and on maps are not always put in place on the ground. Many of those that do exist face a disheartening array of threats, ranging from the immediate impacts of poaching or illegal logging to subtle effects of air pollution or climate change. -

Turgut Özal'in Başbakanliği Döneminde Türkiye-Abd

T.C. İstanbul Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Uluslararası İlişkiler Anabilim Dalı Doktora Tezi TURGUT ÖZAL’IN BAŞBAKANLIĞI DÖNEMİNDE TÜRKİYE-ABD İLİŞKİLERİ Sibel Kavuncu 2502010142 Tez Danışmanı Prof. Dr. Faruk Sönmezoğlu İstanbul, 2006 ÖZ Turgut Özal’ın Başbakanlığı Döneminde Türkiye-ABD İlişkilerini konu alan çalışma, esas olarak bir süreç analizi, bir diplomasi tarihi çalışmasıdır. Çalışmada, iki ülke ilişkilerinin hangi zeminde cereyan ettiğinin anlaşılabilmesi için ilk olarak uluslararası ortamın dönem içindeki görünümü incelenmiştir. 1970’lerin ikinci yarısından itibaren iki kutuplu sistemin yavaş yavaş yumuşamaya başladığı bir dönemde, Sovyetler Birliği’nin 1979’da Afganistan’ı işgal etme kararı ve İran’daki rejim değişikliği ile uluslararası sistem tekrar sertleşmiştir. ABD’de Sovyetler’e karşı sertlik politikası izleyeceğini söyleyen Ronald Reagan’ın seçimleri kazanarak işbaşına gelmesi ise, iki kutup arasındaki karşılıklı güvensizliği iyice arttırmış, “yeni soğuk savaş” sözleri duyulmaya başlanmıştır. Bu koşulların hakim olduğu dönemin uluslararası ortamı içinde ABD ve Türkiye’nin durumları siyasi, askeri ve ekonomik açılardan değerlendirilerek iki ülke ilişkilerinde rol oynayan ve ilişkilere yön veren etmenlerin ortaya konulmasında bir çerçeve oluşturulmaya çalışılmıştır. İkinci olarak, Turgut Özal’ın Başbakan olduğu yıllarda dış politikaya bakışı, dış politika yönelimleri ele alınarak, Özal yönetimince o dönemde ABD’ye nasıl bakıldığı, nasıl bir tutum benimsendiği incelenmiştir. Dönem içinde ABD’nin Türkiye değerlendirmesi de ele alınarak yaklaşımlarda bir karşılaştırmaya gidilmiştir. Çalışmanın son bölümünde ise genel olarak Turgut Özal’ın Başbakanlığı döneminde Türkiye-ABD ilişkilerinde “artan bir iyileşme” olduğu şeklindeki yaygın kanının aksine, iki ülke ilişkilerinde birçoğu doğrudan ikili ilişkilerden kaynaklanmasa da birdizi sorun olduğu ortaya konulmuş, dönem boyunca bu sorunların birbiriyle bağlantılı bir şekilde sürekli olarak gündeme geldiğine işaret edilmiştir.