Long-Term Group Membership and Dynamics in a Wild Western Lowland Gorilla Population (Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla) Inferred Using Non-Invasive Genetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-River Gorillas

CMS Agreement on the Distribution: General Conservation of Gorillas UNEP/GA/MOP3/Inf.9 and their Habitats of the 24 April 2019 Convention on Migratory Species Original: English THIRD MEETING OF THE PARTIES Entebbe, Uganda, 18-20 June 2019 REVISED REGIONAL ACTION PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATION OF THE CROSS RIVER GORILLA (Gorilla gorilla diehli) 2014 - 2019 For reasons of economy, this document is printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. FewerToday, thethan total population of Cross River gorillas may number fewer than 300 individuals 300 left Revised Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) 2014–2019 HopeUnderstanding the status of the changing threats across the Cross River gorilla landscape will provide key information for guiding our collectiveSurvival conservation activities cross river gorilla action plan cover_2013.indd 1 2/3/14 10:27 AM Camera trap image of a Cross River gorilla at Afi Mountain Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) This plan outlines measures that should ensure that Cross River gorilla numbers are able to increase at key core sites, allowing them to extend into areas where they have been absent for many years. cross river gorilla action plan cover_2013.indd 2 2/3/14 10:27 AM Revised Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) 2014-2019 Revised Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) 2014-2019 Compiled and edited by Andrew Dunn1, 16, Richard Bergl2, 16, Dirck Byler3, Samuel Eben-Ebai4, Denis Ndeloh Etiendem5, Roger Fotso6, Romanus Ikfuingei6, Inaoyom Imong1, 7, 16, Chris Jameson6, Liz Macfie8, 16, Bethan Mor- gan9, 16, Anthony Nchanji6, Aaron Nicholas10, Louis Nkembi11, Fidelis Omeni12, John Oates13, 16, Amy Pokemp- ner14, Sarah Sawyer15 and Elizabeth A. -

Western Gorilla Social Structure and Inter-Group Dynamics

Western Gorilla Social Structure and Inter-Group Dynamics Robin Morrison Darwin College This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2019 Declaration of Originality This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. Statement of Length The word count of this dissertation is 44,718 words excluding appendices and references. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the Archaeology and Anthropology Degree Committee. II Western Gorilla Social Structure and Inter-Group Dynamics Robin Morrison The study of western gorilla social behaviour has primarily focused on family groups, with research on inter-group interactions usually limited to the interactions of a small number of habituated groups or those taking place in a single location. Key reasons for this are the high investment of time and money required to habituate and monitor many groups simultaneously, and the difficulties of making observations on inter-group social interaction in dense tropical rainforest. -

GORILLA Report on the Conservation Status of Gorillas

Version CMS Technical Series Publication N°17 GORILLA Report on the conservation status of Gorillas. Concerted Action and CMS Gorilla Agreement in collaboration with the Great Apes Survival Project-GRASP Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences 2008 Copyright : Adrian Warren – Last Refuge.UK 1 2 Published by UNEP/CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. Recommended citation: Entire document: Gorilla. Report on the conservation status of Gorillas. R.C. Beudels -Jamar, R-M. Lafontaine, P. Devillers, I. Redmond, C. Devos et M-O. Beudels. CMS Gorilla Concerted Action. CMS Technical Series Publication N°17, 2008. UNEP/CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. © UNEP/CMS, 2008 (copyright of individual contributions remains with the authors). Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is cited and the copyright holder receives a copy of the reproduced material. Reproduction of the text for resale or other commercial purposes, or of the cover photograph, is prohibited without prior permission of the copyright holder. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP/CMS, nor are they an official record. The designation of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP/CMS concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, nor concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. Copies of this publication are available from the UNEP/CMS Secretariat, United Nations Premises. -

The One and Only Ivan Activity Packet

© 2020 Disney © 2020 Disney n adaptation of the award-winning book about one very special Agorilla, Disney’s “The One and Only Ivan” is an unforgettable tale about the beauty of friendship, the power of visualization and the significance of the place one calls home. Ivan is a 400-pound silverback gorilla who shares a communal habitat in a suburban shopping mall with Stella the elephant and Bob the dog. He has few memories of the jungle where he was captured, but when a baby elephant named Ruby arrives, it touches something deep within him. Ruby is recently separated from her family in the wild, which causes him to question his life, where he comes from and where he ultimately wants to be. The heartwarming adventure, which comes to the screen in an impressive hybrid of live-action and CGI, is based on Katherine Applegate’s bestselling book, which won numerous awards upon its publication in 2013, including the Newbery Medal. 2 © 2020 Disney CONTENTS Acknowledgements Disney’s Animals, Science and Environment would like to take 4 this opportunity to thank the amazing teams that came together to develop “The One and Only Ivan” Activity Packet. It was created with great care, collaboration and the talent and hard work of many incredible individuals. A special thank you to Dr. Mark Penning for 5 his ongoing support in developing engaging educational content that connects families with nature. These materials would not have happened without the diligence and dedication of Kyle Huetter who worked side by side with the filmmakers to help create these compelling activities. -

Genetic Variation in Gorillas

American Journal of Primatology 64:161–172 (2004) RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic Variation in Gorillas LINDA VIGILANT* and BRENDA J. BRADLEY Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany This review summarizes what is currently known concerning genetic variation in gorillas, on both inter- and intraspecific levels. Compared to the human species, gorillas, along with the other great apes, possess greater genetic varation as a consequence of a demographic history of rather constant population size. Data and hence conclusions from analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), the usual means of describing intraspecific patterns of genetic diversity, are limited at this time. An important task for future studies is to determine the degree of confidence with which gorilla mtDNA can be analyzed, in view of the risk that one will inadvertently analyze artifactual rather than genuine sequences. The limited information available from sequences of nuclear genomic segments does not distinguish western from eastern gorillas, and, in comparison with results from the two chimpanzee species, suggests a relatively recent common ancestry for all gorillas. In the near future, the greatest insights are likely to come from studies aimed at genetic characterization of all individual members of social groups. Such studies, addressing topics such as behavior of individuals with kin and non-kin, and the actual success of male reproductive strategies, will provide a link between behavioral and genetic studies of gorillas. Am. J. Primatol. 64:161–172, 2004. r 2004 Wiley-Liss, Inc. Key words: phylogeography; mtDNA; noninvasive samples; numt; genotype INTRODUCTION Genetic Variation in Wild Animal Populations Studies of genetic variation within a wild animal taxon commonly address two topics: an estimation of the amount of variation present in both individuals and populations, and a description of how that variation is geographically distributed [Avise, 2000]. -

Variation in the Social Organization of Gorillas:Life History And

Received: 1 February 2018 Revised: 18 July 2018 Accepted: 6 August 2018 DOI: 10.1002/evan.21721 REVIEW ARTICLE Variation in the social organization of gorillas: Life history and socioecological perspectives Martha M. Robbins | Andrew M. Robbins Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany Abstract Correspondence A focus of socioecological research is to understand how ecological, social, and life history factors Martha M. Robbins, Max Planck Institute for influence the variability of social organization within and between species. The genus Gorilla Evolutionary Anthropology, Deutscher Platz exhibits variability in social organization with western gorilla groups being almost exclusively one- 6, 04103 Leipzig, Germany. Email: [email protected] male, yet approximately 40% of mountain gorilla groups are multimale. We review five ultimate Funding information causes for the variability in social organization within and among gorilla populations: human dis- Max Planck Society turbance, ecological constraints on group size, risk of infanticide, life history patterns, and popula- tion density. We find the most evidence for the ecological constraints and life history hypotheses, but an over-riding explanation remains elusive. The variability may hinge on variation in female dispersal patterns, as females seek a group of optimal size and with a good protector male. Our review illustrates the challenges of understanding why the social organization of closely related species may deviate from predictions based on socioecological and life history theory. KEYWORDS dispersal, infanticide, male, male philopatry, multimale groups, relatedness 1 | INTRODUCTION to understand variability in within-species and between-species grouping patterns researchers should consider how feeding competi- Some of the earliest comparative analyses seeking to understand vari- tion and predation interact with variation in reproductive strategies ability in primate social organization focused on the occurrence of the and life history parameters of both sexes. -

Western-Lowland-Gorilla.Pdf

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Gorilla gorilla Classification What groups does this organism belong to based on characteristics shared with other organisms? Class: Mammalia (all mammals) Order: Primates (apes, prosimians, monkeys and humans) Family: Hominidae (orangutans, bonobos, chimpanzees, gorillas) Genus: Gorilla (gorillas) Species: Gorilla gorilla Distribution Where in the world does this species live? Western lowland gorillas are widely distributed throughout Western Central Africa’s Congo Basin, inhabiting Angola, Gabon, Cameroon, Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and Equatorial Guinea. Habitat What kinds of areas does this species live in? Inhabits a variety of moist, lowland forest types and swamps, from sea level to about 8,000 feet (2,438 m). Physical Description How would this animal’s body shape and size be described? • Western lowland gorillas are four and a half to five and a half feet tall (1.4-1.75 m) when standing on their two legs. • Males weigh 300 to 600 pounds (136-272 kg). Females weigh 150 to 300 pounds (113-136 kg). • Skin is black and body hair is black with a brownish/grey tinge. Forehead is topped with a reddish/brown cap. • Mature males, called silverbacks, have silvery-grey hair on their backs and thighs. • Muscular arms are much longer than legs. • Strong jaw muscles are attached to a bony ridge (sagittal crest) on the top of the head, especially large in mature males. Diet What does this species eat? In their historic range: Primarily herbivores that consume large quantities of leaves, roots, shoots, pith, bark and fruit. Water is primarily derived from vegetation. At the zoo: Vegetables (including lots of celery), greens, browse, alfalfa, low starch biscuits and small amounts of fruit. -

Studia Muzealne Zeszyt Xxii / 2017 Muzealne Zeszyt Studia

MUZEUM NARODOWE W POZNANIU • ZESZYT XXII • 2017 ROK ISBN 978-83-64080-11-1 ISSN 0137-5318 STUDIA MUZEALNE ZESZYT XXII / 2017 MUZEALNE ZESZYT STUDIA ZESZYT XXII POZNAŃ 2017 Redakcja: Wojciech Suchocki, Adam Soćko Sekretarz redakcji: Agnieszka Skalska Autorzy: Inga Głuszek, Maria Gołąb, Tadeusz I. Grabski, Paweł Ignaczak, Kamila Kłudkiewicz, Tadeusz Wojciech Lange, Jakub Mosiejczyk, Agnieszka Patała, Juliusz Raczkowski, Danuta Rościszewska Recenzenci: Mariusz Bryl, Piotr Juszkiewicz, Adam Labuda Tłumaczenie streszczeń na język angielski: Marcin Turski Redakcja wydawnicza: Magdalena Knapowska Projekt graficzny: Ewa Wąsowska Skład i przygotowanie do druku: Lucyna Majchrzak Opracowanie materiału ilustracyjnego: Tomasz Niziołek Kierownictwo produkcji: Urszula Namiota Fotografie: Adam Cieślawski, Jakub Baszczyński (Pracownia Fotografii Cyfrowej MNP), Katarzyna Giesz- czyńska-Nowacka, Tadeusz I. Grabski, Monika Jakubek-Raczkowska, Kamila Kłudkiewicz, Agnieszka Patała, Marek Peda, Arkadiusz Podstawka, Juliusz Raczkowski; Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu, Одесский художественный музей w Odessie, Thorvaldsens Museum w Kopenhadze, www.zabytki.ocalicodzapomnienia.eu Zgoda na zamieszczenie fotografii: Monika Jakubek-Raczkowska, Kamila Kłudkiewicz, Agnieszka Patała, Juliusz Raczkowski, Fundacja im. Raczyńskich przy Muzeum Narodowym w Poznaniu, Kościół św. Micha- ła Archanioła w Osetnie, Kościół św. Bartłomieja w Nowogrodzie Bobrzańskim, Kościół pw. Matki Bożej Bolesnej w Dzikowicach, Kościół św. Katarzyny w Gościszowicach, Kościół św. Mikołaja w Mycielinie, Kościół św. Marii Magdaleny w Nowym Miasteczku, Kościół św. Wawrzyńca w Babimoście, Musée de l’oeuvre de Notre-Dame, Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu, Одесский художественный музей w Odessie, Thorvaldsens Museum w Kopenhadze Druk: Zakład Poligraficzny Moś i Łuczak Sp.j., Poznań Dział Handlowy Muzeum Narodowego w Poznaniu, Aleje Marcinkowskiego 9, 61-745 Poznań, tel. -

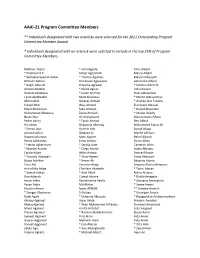

AAAI-21 Program Committee Members

AAAI-21 Program Committee Members ** Individuals designated with two asterisks were selected for the 2021 Outstanding Program Committee Member Award. * Individuals designated with an asterisk were selected to include in the top 25% of Program Committee Members. Mathieu ’Aquin * John Agosta Chris Alberti * Prathosh A P Forest Agostinelli Marco Alberti * Sathyanarayanan Aakur * Thomas Agotnes Marjan Albooyeh Mohsen Abbasi Don Joven Agravante Alexandre Albore * Ralph Abboud Priyanka Agrawal * Stefano Albrecht Ahmed Abdelali * Derek Aguiar Vidal Alcazar Ibrahim Abdelaziz * Julien Ah-Pine Huib Aldewereld Tarek Abdelzaher Ranit Aharonov * Martin Aleksandrov Afshin Abdi Sheeraz Ahmad * Andrea Aler Tubella S Asad Abdi Wasi Ahmad Francesco Alesiani Majid Abdolshah Saba Ahmadi * Daniel Alexander Mohammad Abdulaziz Zahra Ahmadi * Modar Alfadly Naoki Abe Ali Ahmadvand Gianvincenzo Alfano Pedro Abreu * Faruk Ahmed Ron Alford Rui Abreu Shqiponja Ahmetaj Mohammed Eunus Ali * Erman Acar Hyemin Ahn Daniel Aliaga Avinash Achar Qingyao Ai Malihe Alikhani Rupam Acharyya Marc Aiguier Rahaf Aljundi Panos Achlioptas Esma Aimeur Oznur Alkan * Hanno Ackermann * Sandip Aine Cameron Allen * Maribel Acosta * Diego Aineto Adam Allevato Carole Adam Akiko Aizawa Amine Allouah * Sravanti Addepalli * Nirav Ajmeri Faisal Almutairi Bijaya Adhikari * Kenan Ak Eduardo Alonso Yossi Adi Yasunori Akagi Amparo Alonso-Betanzos Aniruddha Adiga Charilaos Akasiadis * Tansu Alpcan * Somak Aditya * Alan Akbik Mario Alviano Don Adjeroh Cuneyt Akcora * Daichi Amagata Aaron Adler Ramakrishna -

Western Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla) Diet and Activity Budgets: Effects of Group Size, Age Class and Food Availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki

Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) diet and activity budgets: effects of group size, age class and food availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki National Park, Central African Republic Terence Fuh MSc Primate Conservation Dissertation 2013 Dissertation Course Name: P20107 Title: Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) diet and activity budgets: effects of group size, age class and food availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki National Park, Central African Republic Student Number: 12085718 Surname: Fuh Neba Other Names: Terence Course for which acceptable: MSc Primate Conservation Date of Submission: 13th September 2013 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the regulations for an MSc degree. Oxford Brookes University ii Statement of originality Except for those parts in which it is explicitly stated to the contrary, this project is my own work. It has not been submitted for any degree at this or any other academic or professional institution. ……………………………………………. ………………… Signature Date Regulations Governing the Deposit and Use of Oxford Brookes University Projects/ Dissertations 1. The “top” copies of projects/dissertations submitted in fulfilment of programme requirements shall normally be kept by the School. 2. The author shall sign a declaration agreeing that the project/ dissertation be available for reading and photocopying at the discretion of the Head of School in accordance with 3 and 4 below. 3. The Head of School shall safeguard the interests of the author by requiring persons who consult the project/dissertation to sign a declaration acknowledging the author’s copyright. 4. Permission for any one other then the author to reproduce or photocopy any part of the dissertation must be obtained from the Head of School who will give his/her permission for such reproduction on to an extent which he/she considers to be fair and reasonable. -

Mise En Page 2

LivretRDC221210.qxd 8/01/11 15:01 Page 1 PROGRAMME CASQUETTES VERTES RD CONGO • Biodiversité • Bonobos • Développement durable • Bikelamo binso • Bonobos • Bokolisi mboka bokoumela Apprendre avec les Casquettes vertes Koyekola elöngö na ba Casquettes vertes Programme soutenu par : Awely, des animaux et des hommes 12 place du Chatelet - 45000 Orléans - France / www.awely.org - [email protected] ONG de statut associatif Loi 1901 - Siret : 484 353 610 00039 ACTION LivretRDC221210.qxd 8/01/11 15:01 Page 3 PROGRAMME CASQUETTES VERTES RD CONGO LivretRDC221210.qxd 8/01/11 15:01 Page 5 table des COMMENÇONS PAR UNE HISTOIRE… 4 - 7 TOBANDELA NA MWA LISOLO... LA BIODIVERSITÉ C’EST QUOI ? 8 - 11 BIKELAMO BINSÖ NDE BANANI ? En tant que Casquette verte d’Awely, Bo Casquette verte ya Awely, nazali matières MIEUX CONNAÎTRE LA FORÊT CONGOLAISE 12 - 17 MALAMU KOBEYA ZAMBA YA CONGO je suis heureux de te présenter na esengo ya bopesi yo buku eye, lokasa la MIEUX CONNAÎTRE LES BONOBOS 18 - 25 MALAMU KOYEBA BABONOBO ce livret dans lequel tu trouveras plein oyo okokuta bansango ebele oyo itali mateya LES CONSÉQUENCES DE LA CHASSE 26 - 27 MAMBI MABE MAKOUTAKA NA BOKILA d’informations sur ton environnement. etando ya mokili na yö. LE DÉVELOPPEMENT DURABLE, 28 - 33 BOKOLISI MBOKA BOKOUMELA, Amuse toi bien ! Misakana malamu ! UN BIEN POUR TOUS BOLAMU BWA BATO BANSO COMMENT VOUS IMPLIQUER ? 34 - 35 NDENGE NINI OKOKI KOMIPESA ? LivretRDC221210.qxd 8/01/11 15:01 Page 7 COMMENÇONS PAR UNE HISTOIRE COMMENÇONS PAR UNE HISTOIRE - TOBANDELA NA MWA LISOLO TOBANDELA NA MWA LISOLO Lobi eleki Tango na kala, bato bazalaki kobika na Lelo boyokani bolamu kati na bango na zamba na Aujourd’hui bango. -

Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla ) in Apenheul Primateapenheul in ) Park Gorilla Do ) 144 Roth Et Al

Evidence-based practice Duckling-catching by a zoo-housed western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) Tom S. Roth1, Thomas R. Bionda2, Elisabeth H. M. Sterck1, 3 1Animal Ecology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands 2Apenheul Primate Park, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands 3Ethology Research, BPRC, Rijswijk, The Netherlands JZAR Evidence-based practice Evidence-based JZAR Correspondence: Elisabeth H. M. Sterck: [email protected] Keywords: hunting; meat eating; Abstract innovation; allocare; gorilla; local wildlife Surveys show that zoo-housed great apes occasionally interact with local wildlife. Bonobos and chimpanzees interact aggressively with and sometimes consume wildlife. Gorillas may also interact Article history: with local wildlife, but less often in an aggressive way and consumption is rare. Here we report the Received: 04 Jul 2018 case of an adolescent female western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) in Apenheul Primate Park Accepted: 18 Apr 2019 (Apeldoorn, The Netherlands) that persistently catches and handles ducklings. Prior to observations Published online: 31 Jul 2019 four possible explanations were proposed, which are not mutually exclusive: play, meat eating, need for abnormal plucking, and allomothering. On eight occasions the female was observed to actually catch ducklings (9 ducklings in total) and the minimum number handled was 19 unique ducklings. She handed ducklings on 10 out of 17 observation days. Ad libitum observations showed that the OPEN ACCESS female spent much time plucking the feathers of the duckling, handling it carefully. In addition, she regularly placed a duckling on her back during locomotion. Eating of a carcass was not observed and playing with a carcass was very rare.