Copyright © 2016 Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. All Rights Reserved. The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal "All Who Love Our Blessed Redeemer" Graham, L.A. 2021 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Graham, L. A. (2021). "All Who Love Our Blessed Redeemer": The Catholicity of John Ryland Jr. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT “ALL WHO LOVE OUR BLESSED REDEEMER” The Catholicity of John Ryland Jr ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor of Philosophy aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit Religie en Theologie op dinsdag 19 januari 2021 om 13.45 uur in de online bijeenkomst van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Lon Alton Graham geboren te Longview, Texas, Verenigde Staten promotoren: prof.dr. -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free

Issue 81: John Newton: Author of “Amazing Grace” John Newton: Did You Know? Interesting and unusual facts about John Newton's life and times Newton the muse Did Newton inspire the writers of Europe's Romantic movement? Various critics have seen him as anticipating Blake's prophetic vision, or as a source for Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" or for episodes in Wordsworth's "Prelude." Man in the middle Even John Wesley recognized the role Newton played in forging a "center" for evangelical Christianity. He wrote to Newton, "You appear to be designed by Divine Providence for an healer of breaches, a reconciler of honest but prejudiced men, and an uniter (happy work!) of the children of God that are needlessly divided from each other." Yes, that's 216 welts When caught attempting to leave the Royal Navy, into which he had been impressed against his will, Newton was whipped 24 times with a cat-o'-nine-tails (similar to the whip in the eighteenth-century scene above). This was actually the lighter punishment for going absent without leave. He could have been hung for desertion. Those … blessed Yankees In June of 1775, after news of the first shots of the War of American Independence broke, Newton's Olney parishioners held an impromptu early-morning prayer meeting. Newton reported to Lord Dartmouth, Olney's Lord of the Manor and Secretary of State for the American Colonies, that between 150 and 200 people turned out at five o'clock in the morning. Newton spoke about the state of the nation, and for an hour the group sang and prayed together. -

International Bulletin of Missionary Research, Vol 36, No. 3

Vol. 36, No. 3 July 2012 Faith, Flags, and Identities n March 24–25, 2011, Duke Divinity School, Durham, ONorth Carolina, hosted a two-day conference focused on the somewhat cumbersome theme “Saving the World? The On Page Changing Terrain of American Protestant Missions, 1910 to the 115 Change and Continuity in American Protestant Present” (see http://isae.wheaton.edu/projects/missions). Orga- Foreign Missions nized and sponsored by Wheaton College’s Institute for the Study Edith L. Blumhofer of American Evangelicals, the conference involved nearly one hundred academ- 115 The Presbyterian Church in Canada’s Mission ics, who presented to Canada’s Native Peoples, 1900–2000 and listened to Peter Bush papers and lec- 122 Pentecostal Missions and the Changing tures exploring the Character of Global Christianity evolving nature of Heather D. Curtis American Protes- The Sister Church Phenomenon: A Case Study tant missions since 129 of the Restructuring of American Christianity the Edinburgh Against the Backdrop of Globalization World Mission- ary Conference of Janel Kragt Bakker 1910, and who dis- 136 Changes in African American Mission: cussed the nation’s Rediscovering African Roots Courtesy of Affordable Creations, http://peggymunday.blogspot.com continuing influ- Mark Ellingsen ence on Christianity globally. This issue of the journal is pleased to 138 Noteworthy feature five of the papers presented at this conference. “Americans,” the late Tony Judt observed, “have trouble 143 The Wesleys of Blessed Memory: Hagiography, with the idea that they are not the world’s most heroic warriors Missions, and the Study of World Methodism or that their soldiers have not fought harder and died braver Jason E. -

History of the Church Missionary Society", by E

Durham E-Theses The voluntary principle in education: the contribution to English education made by the Clapham sect and its allies and the continuance of evangelical endeavour by Lord Shaftesbury Wright, W. H. How to cite: Wright, W. H. (1964) The voluntary principle in education: the contribution to English education made by the Clapham sect and its allies and the continuance of evangelical endeavour by Lord Shaftesbury, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9922/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE VOLUNTARY PRINCIPLE IN EDUCATION: THE CONTRIBUTION TO ENGLISH EDUCATION MADE BY THE CLAPHAil SECT AND ITS ALLIES AM) THE CONTINUAi^^CE OP EVANGELICAL EI-JDEAVOUR BY LORD SHAFTESBURY. A thesis for the degree of MoEd., by H. T7right, B.A. Table of Contents Chapter 1 The Evangelical Revival -

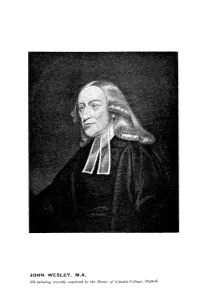

JOHN WESLEV, M.A. Oit Pat"Niing Yf'ceutly Acquired by the Rector of L£Ucoln College, Oxford

JOHN WESLEV, M.A. Oit pat"niing Yf'ceutly acquired by the Rector of L£ucoln College, Oxford. PROCitEDINGS, ANOTHER PORTRAIT OF JOHN WESLEY AT LINCOLN COLLEGE, OXFORD· The Rector of Lincoln College has recently acquired a portrait of John Wesley of which he kindly sends us a photograph. At present the name of the painter appears to be unknown. For purposes of comparison we have sent to Oxford copies of the best known portraits of Wesley in his later years, including two of Romney's (1789), Hamilton's (1789), and Jackson's well known synthetic portrait, painted in 1827. · The Rector suggest! that in some respects the newly discovered portrait resembles Hamilton's. The writer of this note asks : is it a replica by Jackson, or a copy of his original painting at the 1 Book Room '? It is uncertain who possessed it before it came into the hands of 1 a dealer'. Can any member of the W. H. S. throw light upon it? We have not yet seen the oil painting itself. If some reader is able to do so, with the Rector's permission, he will want to compare it with other portraits. The critic will know something of technique, of composition, and colour. He will be able to discern what pigments were used by the painter. He will enquire if on the painting, or canvass, or frame, there is any trace of a name, or date. He may recall Ruskin's saying (in Modern Painter1), 1 there is not the face which the painter may not make ideal if he choose ; but that subtle feeling which shall find out all of good that there is in any given countenance is not, except by concern for other things than art, to be acquired.' He will agree with P. -

15 R.T. KENDALL and WESTMINSTER Editor ^

k f!l! f • 1 EDITORIAL 3 THE LEGACY OF THE 19th CENTURY Robert Oliver 11 PAUL'S TEACHING ON MARRIAGE Victor Budgen 15 R.T. KENDALL AND WESTMINSTER Editor ^ 19 CHRISTIAN FELLOWSHIP Jeff Saunders 71 N.E.A.C. AND ROME and other correspondence 29 THE LIFE OF A. W. PINK Ray Leviok 35 TWO NEW HYMN BOOKS REVIEWED Editor 37 JOHN OWEN AND 2 PETER 3:9 Bob Letharr) 40 GRACE BAPTIST CHURCH—DUBLIN io to Editorial The Legacy of the Nineteenth Century Men entering the ministry today soon discover that there are traditions in the Church which come to us as a legacy of the nineteenth century—a legacy of dubious value. Traditions which can hinder progress, stick hard and are difficult to remove. Reformation is exceed ingly difficult. Long patience and enduring perseverance are necessary. It is no small help to understand how these traditions originated. Robert Oliver's historical survey gives us some idea. Whenever the Church departs from a powerful doctrinal, expository, systematic, teaching ministry she exposes herself to deadly errors and heresies. A lack of definitive doctrine made way during the last century for the overwhelming advance of Liberalism. The poor evangelical forces were ill-equipped to stand before the armed might and blitz-krieg of the higher critical movement. A lack of doctrinal strength in the Established Church meant that a fertile field was ready to receive the seeds of a resurgent Romanism in the Church of England. In his first study Robert Oliver traced out the advance of Liberalism and described the advance of an expanding Romanism. -

Professor Ff Bruce, Ma, Dd the Inextinguishable Blaze

The Paternoster Ch11rch History, Vol. VII General Editor: PROFESSOR F. F. BRUCE, M.A., D.D. THE INEXTINGUISHABLE BLAZE In the Same Series: Vol. I. THE SPREADING FLAME The Rise and Progress of Christianity l!J Professor F. F. Bruce, M.A., D.D. Vol. II. THE GROWING STORM SketrhesofChurchHistoryfromA.D. 6ootoA.D. IJJO i!J G. S. M. Walker, M.A., B.D., Ph.D. Vol. III. THE MORNING STAR Wycliffe and the Dawn of the Reformation l!J G. H. W. Parker, M.A., M.Litt. Vol. VI. LIGHT IN THE NORTH The Story of the Scottish Covenanters l!J J. D. Douglas, M.A., B.D., S.T.M., Ph.D. Vol. VIII. THE LIGHT OF THE NATIONS Evangelical Renewal and Advance in the Nineteenth Century l!JJ. Edwin Orr, Ph.D., D. Phil. (Oxon), F.R.Hist.S. In Preparation: Vol. IV. THE GREAT LIGHT Luther and the Reformation l!J James Atkinson, M.A., M.Litt., D.Th. Vol. V. THE REFINING FIRE The Puritan Era l!J James Packer, M.A., D.Phil. THE INEXTINGUISHABLE BLAZE SpiritlltlJ Renewal and Advance in the Eighteenth Century by A. SKEVINGTON WOOD B.A., Ph.D., F.R.Hist.S. Then let it for Thy glory h11r11 With inextingllishahle bla:<.e,· And trembling to its source return, In humble prayer and fervent praise. Charles Wesley PATERNOSTER • THE PATERNOSTER PRESS C Copyright 1900 The Patm,oster Press Second impru.rion Mar,h 1967 AUSTRALIA: Emu Book Agmriu Pty., Ltd., pr, Kent Streit, Sydney, N.S.W. CANADA: Hom, E11angel Books Ltd., 2.5, Hobson A11enue, Toronto, 16 SOUTH AFRICA: Oxford University Prus, P.O.Box u41, Thibault Ho11.re, Thibault Square, Cape Town NEW ZEALAND: G. -

One Hundred Years

ONE HUNDRED YEARS BEING THE SHORT HISTORY OF THE CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY "1tbou ebalt remember all tbe wa'!? wblcb tbe 1orb tb'!? Gob kb tbec." ,DET. Tiii. ! ~birlJ <$bition LONDON CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY SALISBURY SQUARE, E.C. 1899 PREFACE. HIS little book has been written for publication in advance of the complete· History of the Church Missionary Society. The greater part of it con sists of a very brief summary of some of the facts D given in the larger work ; and here and there sentences and paragraphs are actually reproduced from the still unpublished volumes. But part of Chapter IX., and Chapters X. and XI., have had to be written before the corresponding portions of the complete History. · To many of the most · important parts of the complete History, however, there is nothing corresponding in these pages. For the History dwells at some length upon the environment of the Society at different periods in the century, that is to say, upon the state of the Church of England at home, noticing various religious movements, developments, and controversies, and introducing such men as Bishops Blomfield and Wilberforce, Archbishops Tait and Benson, Lords Shaftesbury and Cairns, Sir Arthur Blackwood and Mr. Pennefather, Bishop Ryle and Canon Hoare. Also upon the progress of Christian Missions generally, with references to the work of men like Bishops Selwyn, Patteson, and Steere, of Morrison, Livingstone, and Hudson Taylor. Also upon public events and affairs abroad which have affected Missions, such as the Slave Trade, African Exploration, the Opium Traffic, the colonization of New Zealand, and a whole series of important events in India. -

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Allen, William, 1770-1843. Life of William Allen, with Selections from His Correspondence. in Three Volum

1 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Allen, William, 1770-1843. Life of William Allen, with Selections From His Correspondence. In Three Volumes. London: Charles Gilpin, 1846-1847. Special Coll. BX7795 .A6 A3 1846 vol. 1, 2, 3 "Chiefly selected from his dairy and correspondence." - Pref. Allen, William, 1770-1843 Anstey, Roger, Christine Bolt and Seymour Drescher. Anti-Slavery, Religion and Reform. First ed. Folkestone, Kent and Hamden Connecticut: Wm. Dawson & Sons, Ltd. and Archon Books, 1980. HT 1025 .A57 1980 "The essays in this volume were first delivered at a Bellagio Conference in 1978 and have since been revised for publication. Taken together, they illuminate the whole complex relationship between anti-slavery, religion and reform in North America, Britain and parts of continental Europe." Wilberforce, William cited in the index for pg. 15, 23, 24, 25, 59, 70, 109, 120, 122, 123, 126, 129, 130, 134, 149, 152, 154, 274n 6, 277, 283, 287, 295, 297, 304, 305, 310, 320, 346 Slaves - Emancipation - Congresses Abolitionists - Congresses Wilberforce, William, 1759-1833 Ayling, Stanley Edward. Edmund Burke; His Life and Opinions. First American ed. London: John Murray Publisher, 1988; reprint, New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1988. DA 506 .B9 A95 1988 Burke's massive correspondence reveals a man intimately and tirelessly engaged, not only with great issues of the day, but also with the details of countless minor matters and ephemeral controversies public and personal. But in the major concerns of the day he rarely failed to penetrate beneath the surface of events to the foundations of principle below William Wilberforce cited on pg. -

Groom Surname Groom Forename

Groom surname Groom Bride Surname Bride Newspaper Wedding Groom abode Groom Bride's abode Bride's Father Forename Forename Date location occupation *ain George Knowles Mary 07/05/1818 Not given Stow-on-the-Wold, Not given Holywell, Oxford Not given Gloucestershire [Harman] Joseph Hancox Miss 26/09/1833 Kingswinford Cleat, Staffordshire Not given Brettell Lane near Not given Stourbridge Abbiss John Cox Miss 28/06/1827 Stourbridge Dudley Not given Stourbridge Not given Abbott Thomas Waring Matilda 08/03/1826 Redditch Redditch Not given Redditch Not given Abbott John Smith Charlotte 18/05/1826 St Martin's Stamford Not given New Street, Worcester Not given Lincolnshire Abbott Richard Scambler Not given 28/04/1825 Redditch Redditch Not given Redditch Not given Abley Not given George Sarah 19/06/1823 Upton-upon- Leominster Not given Upton-upon-Severn Not given Severn Abney A.M Edward Holden Ellen Rose 19/12/1822 West Bromwich Measham Hall, Not given Not given late Hyla Holden Derbyshire Ackroyd William. Walford Sarah 17/06/1830 Halesowen Stourbridge Currier Stourbridge Mr John Walford Acraman William. Edward, Castle Mary 05/09/1822 Clifton Not given Not given Not given Thos. Castle Esq. Esq. Acton John Mrs. Jones Not given 02/08/1832 All Saints , Cheltenham Not given Bridge Street, Not given Worcester Worcester Acton William. Hartland Melina 04/03/1824 Bosbury Hay Breconshire Not given Bosbury Herefordshire Second daughter of late Mr. Jas. Hartland Acton William. Harrington Elizabeth 08/01/1818 Worcester, All Worcester Not given Worcester Not given Saint's Church Acton John Bydawell Alphea 19/02/1824 Bristol Brocastle, Not given Cradley, Herefordshire M. -

The Em.Ergence of the Protestant Evangelical Tradition

The Em.ergence of the Protestant Evangelical Tradition RICHARD TURNBULL It has been increasingly recognized that there are substantial differences between evangelicals. This has become focussed in recent years with the strengthening of the evangelical movement within the Church of England; when a group is in a distinct minority there is much greater emphasis on those unifying aspects rather than differences. The recent divisions over the ordination of women to the presbyterate have only served to heighten the tensions. We should not be surprised by such different concerns and emphases among those that call themselves evangelical. They reflect the diversity of the evangelical tradition from its emergence in the late eigh teenth and early nineteenth centuries. But. as Alister McGrath has said, 'evangelicals are shockingly ignorant of their own heritage.' 1 The purpose of this article is to trace that heritage, and examine how mainstream Protestant evangelicalism emerged. Unity uad diversity In 1783 a group of London evangelical clergy founded the Eclectic Society for conducting theological discussion and the investigation of reli gious truth. For many of the meetings in the period 1798-1814 the notes made by one of the participants, the Revd. Josiah Pratt, later secretary of the Church Missionary Society, were published in 1858 by John Henry Pratt. 2 The members of the Society when the notes began consisted of a number of well-known evangelical clergymen, including the Revd. John Newton, the Revd. Thomas Scott, the Revd. Richard Cecil, the Revd. John Venn, the Revd. Basil Woodd, the Revd. Josiah Pratt; two dissenting min isters, the Revd. -

International Bulletin of Missionary Research, Vol 36, No. 3

The Legacy of Josiah Pratt William C. Barnhart n October 1814 a meeting was held in Birmingham, Eng- Newton, whose ministerial capabilities by this time were quite Iland, to discuss the possibility of forming a local branch limited.3 From 1810 to 1826, coinciding with his most active years of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in that city. During the in the CMS, Pratt was minister at Sir George Wheler’s Chapel in deliberations, Thomas Rock, a Birmingham merchant, rose to Spital Square. He became a beneficed clergyman in 1826 upon make the following statement: “Do we need motive? Let us take his election to the vicarage of St. Stephens in the City of London, it again from the conduct of the worthy Secretary, who is come a position he retained until his death in 1844. from the metropolis of our own country, with his heart filled with love and compassion for the poor heathen: who has labored The CMS and the Anglican Missionary Revival night and day to promote their welfare, and whose name will be handed down to posterity with honor, enrolled among the best In 1797, while serving as curate at St. John’s, Pratt became a friends of the Church Missionary Society.”1 member of the Eclectic Society, an informal gathering of Anglican Rock was referring to the Reverend Josiah Pratt, secretary of Evangelicals to periodically discuss common theological interests the CMS and one of its founding members. He served as CMS and issues. It had been formed in 1783 by two of Pratt’s early secretary from 1802 to 1824, and he also edited the Missionary Register, one of the most important missionary magazines of the early nineteenth century.