Professor Ff Bruce, Ma, Dd the Inextinguishable Blaze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of an Evangelical Tory: the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-1885) and the Evolving Character of Victorian Evangelicalism

The Making of an Evangelical Tory: The Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-1885) and the Evolving Character of Victorian Evangelicalism David Andrew Barton Furse-Roberts A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW School of Humanities & Languages Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences November 2015 CONTENTS Page Abstract i Abbreviations ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction I Part I: Locating Anthony Ashley Cooper within the Anglican Evangelical tradition 1 1.1 Ashley’s expression of Evangelicalism 2 1.2 How the associations and leaders of Anglican Evangelicalism shaped the evolving 32 religious temperament of Ashley. 1.3 Conclusion: A son of the Clapham Sect or a brother of the Recordites? 64 Part II: A just estimate of rank and property: Locating Ashley’s place within the 67 tradition of paternalism 2.1 Identifying the character of Ashley’s paternalism 68 2.2 How Tory paternalist ideas influenced the emerging consciousness of Ashley in the 88 pre-Victorian era 2.3 The place of Ashley’s paternalism within the British Tory and Whig traditions 132 2.4 Conclusion: Paternalism in the ‘name of the people’ 144 Part III: Something admirably patrician in his estimation of Christianity: Ashley 147 and the emerging synthesis between Evangelicalism and Tory paternalism 3.1 Common ground forged between Tory paternalism and early Victorian Evangelicalism 148 3.2 Ashley and the factory reform movement: Project of Tory paternalism or 203 by-product of Evangelical social concern? 3.3 The coalescence of these two belief systems in the emerging political philosophy of 230 Ashley 3.4 Conclusion: Making Evangelicalism a patrician creed 237 Part IV: Ashley and the milieux of Victorian Evangelicalism 240 4.1 Locating Ashley’s place within the Victorian Evangelical Terrain 242 4.2 Thy kingdom come, thy will be done: The premillennial eschatology and 255 Evangelical activism of Ashley 4.3 Desire for the nations: Ashley and Victorian Evangelical attitudes to imperialism, 264 race and the ‘Jewish question’. -

Notes on the Parish of Mylor, Cornwall

C.i i ^v /- NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR /v\. (crt MVI.OK CII r RCII. -SO UIH I'OKCil AND CROSS O !• ST. MlLoKIS. [NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR CORNWALL. BY HUGH P. OLIVEY M.R.C.S. Uaunton BARNICOTT &- PEARCE, ATHEN^UM PRESS 1907 BARNICOTT AND PEARCE PRINTERS Preface. T is usual to write something as a preface, and this generally appears to be to make some excuse for having written at all. In a pre- face to Tom Toole and his Friends — a very interesting book published a few years ago, by Mrs. Henry Sandford, in which the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, together with the Wedgwoods and many other eminent men of that day figure,—the author says, on one occasion, when surrounded by old letters, note books, etc., an old and faithful servant remon- " " strated with her thus : And what for ? she " demanded very emphatically. There's many a hundred dozen books already as nobody ever reads." Her hook certainly justified her efforts, and needed no excuse. But what shall I say of this } What for do 1 launch this little book, which only refers to the parish ot Mylor ^ vi Preface. The great majority of us are convinced that the county of our birth is the best part of Eng- land, and if we are folk country-born, that our parish is the most favoured spot in it. With something of this idea prompting me, I have en- deavoured to look up all available information and documents, and elaborate such by personal recollections and by reference to authorities. -

America, and the Americans ... by a Citizen of the World

Library of Congress America, and the Americans ... By a citizen of the world AMERICA, AND THE AMERICANS. “AUDI ALTERAM PARTEM.” BY A CITIZEN OF THE WORLD. James Broadman LONDON: PRINTED FOR LONGMAN, REES, ORME, BROWN, GREEN, & LONGMAN, PATERNOSTER-ROW. 1833. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CITY OF WASHINGTON 378 973 E165 Bb9 London: Printed by A. & R. Spottiswoode, New-Street-Square. TO LAFAYETTE, THE COMPANION OF WASHINGTON, AND THE FRIEND OF MANKIND, THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE MOST RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED, BY THE AUTHOR. A 2 PREFACE “ WHEN a writer,” says the excellent Paley, “offers a book to the public, upon a subject on which the public are already in possession of many others, he is bound by a kind of literary justice to inform his readers, distinctly and specifically, what it is he professes to supply, and what he expects to improve.” America, and the Americans ... By a citizen of the world http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.26745 Library of Congress In compliance with this injunction, I shall proceed to state the causes which induced me to incur the responsibilities of an author. In the course of my travels and residence in the United States of America, which country I visited solely with commercial views, and unprovided with any direct demands for what are termed civilities, notwithstanding the plague spot, slavery, in one district, I saw so much to cheer the philanthropist, so much to delight the lover of liberty, vi so much to interest even the money-spending, as well as the money-getting class; in short, I saw a nation so much further advanced in all the useful arts, as well as the elegancies of life, than I, in common with the great majority of Englishmen, were willing to believe; that my impressions upon the whole were decidedly favourable, and were freely communicated to all with whom I conversed. -

The Seven Dials Renaissance Newsletter

‘The charity has brought an entire neighbourhood back to life…’ – Colin Davis presenting the first PRIAN national award for projects which have stood the test of time. ‘A great project…’ – Peter Bishop past Director of Environment Camden and Professor of Urban Design at the Bartlett School of Architecture. ‘Seven Dials is one of the great architectural set pieces of London.’ – Dr. John Martin Robinson. Overleaf… A Memorial to Francis Golding and the web edition of the ‘Renaissance Study’ | Newsletter wins the bi-annual Walter Bor Media Award | Updates on: the Renaissance Study web edition | Re-Lighting Seven Dials | Pillar Lighting | Street Name Plates | People’s and Street History Plaques. Sponsorship info at the end. 2014 is the Trust’s 30th year and a very busy one. We have many projects underway, some fully funded and others only partially so. We hope this newsletter might encourage your support in maintaining and enhancing this unusual conservation area – the only quarter of London largely intact from late Stuart England. Our projects which are not fully funded are: the new web edition of the Renaissance Studies which we hope will be as pioneering as the previous printed versions; the People’s Plaques scheme, and our part-time coordinator’s salary. Completing the street improvements is our largest task and we are working with our local authorities and freeholders on a holistic approach. Our origins go back to 1977 when Seven Dials became a Housing Action Area and a Conservation Area with Outstanding Status, one of only 38 out of c. 6,000 in England. -

More Wanderings in London E

1 MORE WANDERINGS IN LONDON E. V. LUCAS — — By E. V. LUCAS More Wanderings in London Cloud and Silver The Vermilion Box The Hausfrau Rampant Landmarks Listener's Lure Mr. Ingleside Over Bemerton's Loiterer's Harvest One Day and Another Fireside and Sunshine Character and Comedy Old Lamps for New The Hambledon Men The Open Road The Friendly Town Her Infinite Variety Good Company The Gentlest Art The Second Post A Little of Everything Harvest Home Variety Lane The Best of Lamb The Life of Charies Lamb A Swan and Her Friends A Wanderer in Venice A W^anderer in Paris A Wanderer in London A Wanderer in Holland A Wanderer in Florence Highways and Byways in Sussex Anne's Terrible Good Nature The Slowcoach and The Pocket Edition of the Works of Charies Lamb: i. Miscellaneous Prose; II. Elia; iii. Children's Books; iv. Poems and Plays; v. and vi. Letters. ST. MARTIN's-IN-THE-FIELDS, TRAFALGAR SQUARE MORE WANDERINGS IN LONDON BY E. V. LUCAS "You may depend upon it, all lives lived out of London are mistakes: more or less grievous—but mistakes" Sydney Smith WITH SIXTEEN DRAWINGS IN COLOUR BY H. M. LIVENS AND SEVENTEEN OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY L'Jz Copyright, 1916, By George H. Doran Company NOV -7 1916 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ICI.A445536 PREFACE THIS book is a companion to A Wanderer in London^ published in 1906, and supplements it. New editions, bringing that work to date, will, I hope, continue to appear. -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free

Issue 81: John Newton: Author of “Amazing Grace” John Newton: Did You Know? Interesting and unusual facts about John Newton's life and times Newton the muse Did Newton inspire the writers of Europe's Romantic movement? Various critics have seen him as anticipating Blake's prophetic vision, or as a source for Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" or for episodes in Wordsworth's "Prelude." Man in the middle Even John Wesley recognized the role Newton played in forging a "center" for evangelical Christianity. He wrote to Newton, "You appear to be designed by Divine Providence for an healer of breaches, a reconciler of honest but prejudiced men, and an uniter (happy work!) of the children of God that are needlessly divided from each other." Yes, that's 216 welts When caught attempting to leave the Royal Navy, into which he had been impressed against his will, Newton was whipped 24 times with a cat-o'-nine-tails (similar to the whip in the eighteenth-century scene above). This was actually the lighter punishment for going absent without leave. He could have been hung for desertion. Those … blessed Yankees In June of 1775, after news of the first shots of the War of American Independence broke, Newton's Olney parishioners held an impromptu early-morning prayer meeting. Newton reported to Lord Dartmouth, Olney's Lord of the Manor and Secretary of State for the American Colonies, that between 150 and 200 people turned out at five o'clock in the morning. Newton spoke about the state of the nation, and for an hour the group sang and prayed together. -

Copyright © 2016 Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2016 Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE PREACHING OF JOHN NEWTON (1725-1807): A GOSPEL-CENTRIC, PASTORAL HOMILETIC OF BIBLICAL EXPOSITION __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. May 2016 APPROVAL SHEET THE PREACHING OF JOHN NEWTON (1725-1807): A GOSPEL-CENTRIC, PASTORAL HOMILETIC OF BIBLICAL EXPOSITION Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Hershael W. York (Chair) __________________________________________ Robert A. Vogel __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Angela, whose faithfulness, diligence, and dedicated service to Christ and to others never cease to amaze and inspire me. “Many daughters have done nobly, but you excel them all.” (Prov 31:29) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . vi Chapter 1. THE STUDY OF JOHN NEWTON AND HIS PREACHING . 1 Introduction . 1 Thesis . 6 Background . 7 Methodology . 8 Summary of Content . 11 2. NEWTON’S LIFE AND MINISTRY . 14 Early Years and Life at Sea . 14 Africa and Conversion . 16 Marriage and Call to Ministry . 19 Ministry in Olney and London . 25 Final Years and Death . 33 3. NEWTON’S PREACHING AND THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY . 36 An Overview of Newton’s Preaching . 36 The Eighteenth-Century Context . 54 The Pulpit in Eighteenth-Century England . 58 4. -

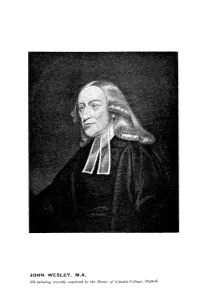

JOHN WESLEV, M.A. Oit Pat"Niing Yf'ceutly Acquired by the Rector of L£Ucoln College, Oxford

JOHN WESLEV, M.A. Oit pat"niing Yf'ceutly acquired by the Rector of L£ucoln College, Oxford. PROCitEDINGS, ANOTHER PORTRAIT OF JOHN WESLEY AT LINCOLN COLLEGE, OXFORD· The Rector of Lincoln College has recently acquired a portrait of John Wesley of which he kindly sends us a photograph. At present the name of the painter appears to be unknown. For purposes of comparison we have sent to Oxford copies of the best known portraits of Wesley in his later years, including two of Romney's (1789), Hamilton's (1789), and Jackson's well known synthetic portrait, painted in 1827. · The Rector suggest! that in some respects the newly discovered portrait resembles Hamilton's. The writer of this note asks : is it a replica by Jackson, or a copy of his original painting at the 1 Book Room '? It is uncertain who possessed it before it came into the hands of 1 a dealer'. Can any member of the W. H. S. throw light upon it? We have not yet seen the oil painting itself. If some reader is able to do so, with the Rector's permission, he will want to compare it with other portraits. The critic will know something of technique, of composition, and colour. He will be able to discern what pigments were used by the painter. He will enquire if on the painting, or canvass, or frame, there is any trace of a name, or date. He may recall Ruskin's saying (in Modern Painter1), 1 there is not the face which the painter may not make ideal if he choose ; but that subtle feeling which shall find out all of good that there is in any given countenance is not, except by concern for other things than art, to be acquired.' He will agree with P. -

Wren St Paul's Cathedral CO Edit

Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723) St. Paul’s Cathedral (1673-1711) Architect: Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723) Nationality: British Work: St. Paul’s Cathedral Date: 1673–1711. First church founded on this site in 604, medieval church re-built after Great Fire of London, 1666. Style: Classical English Baroque Size: Nave 158 x 37m, dome 85m high Materials: Portland stone, brick inner dome and cone, iron chains, timber framed outer dome, lead roof, glass windows, marble floors, wooden screens Construction: Arcuated: classical semi-circular arches; loadbearing walls and piers; ‘gothic’ pointed inner cone, flying buttresses Location: Ludgate Hill highest point of City of London Patron: Church of England Scope of work: Identities specified architect pre-1850 ART HISTORICAL TERMS AND CONCEPTS Function • Dedicated to St Paul, ancient Catholic foundation, now Anglican church under Bishop of London holding religious services with liturgical processions requiring nave, high altar and choirs • Rebuilt as a Protestant or Post-Reformation church, greater emphasis on access to the high altar and hearing the sermon • For Wren the prime requirement was an ‘auditory’ church with an uncluttered interior where all the congregation could see and hear. • Richness of materials and carving communicate the wealth of the city and the nation as well as demonstrating piety • Dome and towers identify presence, location and importance in the area and community. !1 • Inspires awe by the scale of dome soaring to heaven, and heavenly light from windows • Due to large scale of nave used for major national commemorations with large congregations such as state funerals and royal weddings • Contains monuments to significant individuals Watch: https://henitalks.com/talks/sandy-nairne-st-pauls-cathedral/ 6.45 minutes https://www.stpauls.co.uk/visits/visits Introduction for visitors 2.10 mins https://smarthistory.org/stpauls/ 9.06 minutes Dome View from under dome back down nave. -

Public Spirit and Public Order. Edmund Burke and the Role of the Critic in Mid- Eighteenth-Century Britain

Public Spirit and Public Order. Edmund Burke and the Role of the Critic in Mid- Eighteenth-Century Britain Ian Crowe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Jay M. Smith Reader: Professor Christopher Browning Reader: Professor Lloyd Kramer Reader: Professor Donald Reid Reader: Professor Thomas Reinert © 2008 Ian Crowe ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ian Crowe: Public Spirit and Public Order. Edmund Burke and the Role of the Critic in Mid- Eighteenth-Century Britain (Under the direction of Dr. Jay M. Smith) This study centers upon Edmund Burke’s early literary career, and his move from Dublin to London in 1750, to explore the interplay of academic, professional, and commercial networks that comprised the mid-eighteenth-century Republic of Letters in Britain and Ireland. Burke’s experiences before his entry into politics, particularly his relationship with the bookseller Robert Dodsley, may be used both to illustrate the political and intellectual debates that infused those networks, and to deepen our understanding of the publisher-author relationship at that time. It is argued here that it was Burke’s involvement with Irish Patriot debates in his Dublin days, rather than any assumed Catholic or colonial resentment, that shaped his early publications, not least since Dodsley himself was engaged in a revision of Patriot literary discourse at his “Tully’s Head” business in the light of the legacy of his own patron Alexander Pope. -

Agnes De-Courci: a Domestic Tale Place of Publication: Bath Publisher: Printed and Sold for the Author, by S

Author: Anna Maria Bennett Title: Agnes De-Courci: a Domestic Tale Place of publication: Bath Publisher: Printed and sold for the author, by S. Hazard Date of publication: 1789 Edition: 1st ed. Number of volumes: 4 'Variously attributed to Mrs. E. G. Bayfield, J. H. James and Mrs. E. M. Foster.' (The English Novel 1770-1829: a bibliographical survey of prose fiction published in the British Isles, James Raven, Peter Garside & Rainer Schöwerling eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000)) AGNES DE-COURCI, A DOMESTIC TALE. In FOUR VOLUMES. Inscrib’d with Permission to Col. HUNTER. By Mrs. Bennett, AUTHOR OF THE WELCH HEIRESS, and JUVENILE INDISCRETIONS. I know thou wilt grumble, courteous Reader, for every Reader in the World is a Grumbletonion more or less; and for my Part, I can grumble as well as the best of ye, when it is my turn to be a Reader. SCARRON. VOL. I. BATH: PRINTED and SOLD, for the AUTHOR, BY S. HAZARD: Sold also by G.G.J. and J. ROBINSON, Paternoster-Row, and T. HOOKMAN, New Bond-Street, LONDON; SHIER- CLIFF, BRISTOL; and all other Booksellers. MDCCLXXXIX. 2 AGNES. AGNES DE-COURCI, A DOMESTIC TALE. LETTER I. General Moncrass to Major Melrose. Belle Vue. IN the present situation of my affairs, it is equally impossible for me to combat your arguments, or do away the doubts of my prudence; which, notwithstanding your agreeable raillery, I perceive you entertain; time, my dear Major, and time only, will unravel what you term the mystery of my conduct; in the mean while I acknowledge the justness of your position; you draw the parallel between the incertitude of common events, and the natural imbecility of the human mind, with great truth; your conclusions are perhaps severe, but they are not less just, for that severity. -

Car Free Day Map-Lores

E C C E J R O N H O PLA H A H NBU M A N T I GHW WELL L RY A Q TR S S S EET E UNDLE TREET T USE S S ARDEN R L A G R S E 43 E S I E S Steps T L H N 78 127-131 T L A EECH OOR T U RHOU Steps S H P L E K B T Project IGHW T 35 L Y R FARRIN GDORHO NR N N STRE CROWN ARDE L The Charterhouse F A Shakespeare M E C A L I S H S E X C H A N G E G Whitechapel O Gallery ’ KNO C O 1 201 E T The R X 67 T Old A S S QUA R E E R TON ARTE A Square School Tower M 2 125 102 ALK L I T T N Barbican L 1 K A TON WODEHAM R H 42 33 Steps Steps 1 I T T Y S T R E E T T S T REE R Farringdon URY 1 E D PRINC ELET B U K F Rookery C S C O 15 A N P EECH 37 S N N 20 T B Lift U 125 STRE E T H M R PRINCEL ET IRBY F T EET T 104 Steps E 32 GARDE R 34 STR E E 26 Bishops Spitalfields S H Steps M O I Cowcross Street E T T E 56 Barbican NSB E E D Centre C 5 E W L E A FOE HITE 30 N Lauderdale I C E T R V R OW R O S S S T R E T P L E Square K 73 S Y R F C C LA S A T 8 Guildhall School of A R Brady Arts & L E C I LK O CKINGTON ST 36 OSS S S H N N E P P PUM E S I A ALDER A CO 85 Tower Defoe S E Market U R T T 1 U PL L P M T I 60 O Barbican Library TREET A E 3 E A L H I 29 C E L AUDERDAL E Music & Drama - E Community A 93 K W R E R R NDSEY House N S T N L E T E S 6 P L ACE R R EET Brick Lane EET T N L S H 29 to 35 90 F S R S R T PEE 2 D ’ T 25 G L A Milton Court M Centre R R ULBO E C D C 89 H REE CLOTH Steps H S 95 A S C Steps Steps Y Jamme Masjid G Barbican I G T W E A 84 A R OURT E S H R ILSO A TREE NHITL L W E R E U A E 87 A ALK E L D KESIDE TER N O N N U 39 T ST S T Finsbury CL U 176