VU Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Mid-1630S, a Teenager of Welsh Descent by the Name of William Kiffin

P a g e | 1 “AN HONOURABLE ESTEEME OF THE HOLY WORDS OF GOD”: PARTICULAR BAPTIST WORSHIP IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY “I value not the Practice of all Mankind in any thing in God’s Worship, if the Word of God doth not bear witness to it” Benjamin Keach 1 In the mid-1630s, a teenager of Welsh descent by the name of William Kiffin (1616-1701), who had been orphaned as a young boy and subsequently apprenticed to a glover in London, became so depressed about his future prospects that he decided to run away from his master. It was a Sunday when he made good his escape, and in the providence of God, he happened to pass by St. Antholin’s Church, a hotbed of Puritan radicalism, where the Puritan preacher Thomas Foxley was speaking that day on “the duty of servants to masters.” Seeing a crowd of people going into the church, Kiffin decided to join them. Never having heard the plain preaching of a Puritan before, he was deeply convicted by what he heard and was convinced that Foxley’s sermon was intentionally aimed at him. Kiffin decided to go back to his master with the resolve to hear regularly “some of them they called Puritan Ministers.”2 1 The Breach Repaired in God’s Worship: or, Singing of Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs, proved to be an Holy Ordinance of Jesus Christ (London, 1691), p.69. 2 William Orme, Remarkable Passages in the Life of William Kiffin (London: Burton and Smith, 1823), p.3. In the words of one writer, St. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The Capitol Dome

THE CAPITOL DOME The Capitol in the Movies John Quincy Adams and Speakers of the House Irish Artists in the Capitol Complex Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way A MAGAZINE OF HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETYVOLUME 55, NUMBER 22018 From the Editor’s Desk Like the lantern shining within the Tholos Dr. Paula Murphy, like Peart, studies atop the Dome whenever either or both America from the British Isles. Her research chambers of Congress are in session, this into Irish and Irish-American contributions issue of The Capitol Dome sheds light in all to the Capitol complex confirms an import- directions. Two of the four articles deal pri- ant artistic legacy while revealing some sur- marily with art, one focuses on politics, and prising contributions from important but one is a fascinating exposé of how the two unsung artists. Her research on this side of can overlap. “the Pond” was supported by a USCHS In the first article, Michael Canning Capitol Fellowship. reveals how the Capitol, far from being only Another Capitol Fellow alumnus, John a palette for other artist’s creations, has been Busch, makes an ingenious case-study of an artist (actor) in its own right. Whether as the historical impact of steam navigation. a walk-on in a cameo role (as in Quiz Show), Throughout the nineteenth century, steam- or a featured performer sharing the marquee boats shared top billing with locomotives as (as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), the the most celebrated and recognizable motif of Capitol, Library of Congress, and other sites technological progress. -

Henry J Essey a Pastor in Politics

Henry Jessey A Pastor in Politics HAVE decided to speak* about Henry Jessey's politics because I of my suspicion that the time is perhaps once more approaching when, while a service of ordination may become optional for the making of a minister of Christ, a prison sentence may yet become obligatory. So I want to uncover for you the motives which took Jessey into politics and the ambiguities and troubles which attended his commitment. Nevertheless, I do not want you to think that I have deluded myself into believing that I have discovered either a seventeenth century English Martin Luther King or yet one more lily-livered liberal mouthing platitudes about 'involvement' from a safe suburban pulpit. Henry Jessey was a man of his time and not ours. His spiritual and political context was not our context, his arguments were not our arguments, his crises were not our crises, but the question remains whether his deepest concern ought to be ours. Jessey, apart, perhaps, from being an Oxbridge man, was nearly everything a Baptist minister ought to be. He had the grace of perseverance and served one congregation for about a quarter of a century. He was friendly to other Christians, at least within decent limits, for neither papists nor unitarians were invited to the ministers' fraternal to which he belonged. He was good with children, though a bachelor, and had even written a book for them. He was an en thusiastic expositor of Scripture and shared, during the 1650's, in a scheme for replacing the King James Version with a new and more accurate one. -

Serampore: Telos of the Reformation

SERAMPORE: TELOS OF THE REFORMATION by Samuel Everett Masters B.A., Miami Christian College, 1989 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religion at Reformed Theological Seminary Charlotte, North Carolina December, 2010 Accepted: ______________________________ Dr. Samuel Larsen, Project Mentor ii ABSTRACT Serampore: the Telos of the Reformation Samuel E. Masters While many biographies of missionary William Carey have been written over the last two centuries, with the exception of John Clark Marshman’s “The Life and Times of Carey, Marshman and Ward: Embracing the History of the Serampore Mission”, published in the mid-nineteenth century, no major work has explored the history of the Serampore Mission founded by Carey and his colleagues. This thesis examines the roots of the Serampore Mission in Reformation theology. Key themes are traced through John Calvin, the Puritans, Jonathan Edwards, and Baptist theologian Andrew Fuller. In later chapters the thesis examines the ways in which these theological themes were worked out in a missiology that was both practical and visionary. The Serampore missionaries’ use of organizational structures and technology is explored, and their priority of preaching the gospel is set against the backdrop of their efforts in education, translation, and social reform. A sense is given of the monumental scale of the work which has scarcely equaled down to this day. iii For Carita: Faithful wife Fellow Pilgrim iv CONTENTS Acknowledgements …………………………..…….………………..……………………...viii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………….9 The Father of Modern Missions ……………………………………..10 Reformation Principles ………………………………………….......13 Historical Grids ………………………………………………….......14 Serampore and a Positive Calvinism ………………………………...17 The Telos of the Reformation ………………………………………..19 2. -

The Representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night

AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies, Volume2, Number 1, February 2018 Pp. 97-105 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol2no1.7 The Representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night Rachid MEHDI Department of English, Faculty of Art Abderahmane-Mira University of Bejaia, Algeria Abstract This article is a study on the representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night; or, What You Will, one of his most popular comic play in the modern theatre. In mocking Malvolio’s morality and ridiculous behaviour, Shakespeare wanted to denounce Puritans’ sober society in early modern England. Indeed, Puritans were depicted in the play as being selfish, idiot, hypocrite, and killjoy. In the same way, many other writers of different generations, obviously influenced by Shakespeare, have espoused his views and consequently contributed to promote this anti-Puritan literature, which is still felt today. This article discusses whether Shakespeare’s portrayal of Puritans was accurate or not. To do so, the writer first attempts to define the term “Puritan,” as the latter is quite equivocal, then take some Puritans’ characteristics, namely hypocrisy and killjoy, as provided in the play, and analyze them in the light of the studies of some historians and scholars, experts on the post Reformation Puritanism, to demonstrate that Shakespeare’s view on Puritanism is completely caricatural. Keywords: caricature, early modern theatre, Malvolio, Puritans, satire Cite as: MEHDI, R. (2018). The Representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. Arab World English Journal for Translation & Literary Studies, 2 (1). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol2no1.7 Arab World English Journal for Translation & Literary Studies 97 eISSN: 2550-1542 |www.awej-tls.org AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies Volume, 2 Number 1, February 2018 The Representation of Puritans in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night MEHDI Introduction Puritans had been the target of many English writers during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. -

May-June 293-WEB

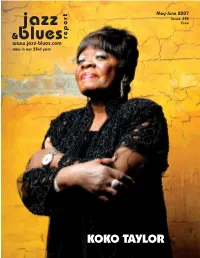

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Menasseh Ben Israel and His World Brill's Studies in Intellectual History

MENASSEH BEN ISRAEL AND HIS WORLD BRILL'S STUDIES IN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY General Editor AJ. VANDERJAGT, University of Groningen Editorial Board M. COLISH, Oberlin College J.I. ISRAEL, University College, London J.D. NORTH, University of Groningen R.H. POPKIN, Washington University, St. Louis-UCLA VOLUME 15 MENASSEH BEN ISRAEL AND HIS WORLD EDITED BY YOSEF KAPLAN, HENRY MECHOULAN AND RICHARD H. POPKIN ^o fr-hw'* -A EJ. BRILL LEIDEN • NEW YORK • K0BENHAVN • KÖLN 1989 Published with financial support from the Dr. C. Louise Thijssen- Schoutestichting. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Menasseh Ben Israel and his world / edited by Yosef Kaplan, Henry Méchoulan and Richard H. Popkin. p. cm. -- (Brill's studies in intellectual history, ISSN 0920-8607 ; v. 15) Includes index. ISBN 9004091149 1. Menasseh ben Israel, 1604-1657. 2. Rabbis-Netherlands- -Amsterdam-Biography. 3. Amsterdam (Netherlands)-Biography. 4. Sephardim--Netherlands--Amsterdam--History--17th century. 5. Judaism--Netherlands--Amsterdam--History--17th century. I. Kaplan, Yosef. II. Popkin, Richard Henry, 1923- BM755.M25M46 1989 296'.092-dc20 89-7265 [B] CIP ISSN 0920-8607 ISBN 90 04 09114 9 © Copyright 1989 by E.J. Brill, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or translated in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, microfiche or any other means without written permission from the publisher PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS BY E.J. BRILI, CONTENTS Introduction, Richard H. Popkin vu A Generation of Progress in the Historical Study of Dutch Sephardic Jewry, Yosef Kaplan 1 The Jewish Dimension of the Scottish Apocalypse: Climate, Cove- nant and World Renewal, Arthur H. -

The Old Northwest and the Texas Annexation Treaty

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 7 Issue 2 Article 5 10-1969 The Old Northwest and the Texas Annexation Treaty Norman E. Tutorow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Tutorow, Norman E. (1969) "The Old Northwest and the Texas Annexation Treaty," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol7/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ea!(t Texas Historical Journal 67 THE OLD NORTHWEST AND THE TEXAS ANNEXATION TREATY NORMAN E. TUTOROW On April 22. 1844. President Tyler submitted the Texas treaty to the United States Senate. sending with it scores of official documents and a catalog of arguments in (avor of annexation.' He offered evidence of popular support within Texas itself for annexation. He also argued that Britain had designs on Texas which, if allowed to mature, would pose Ii serious threat tu the South's "peculiar institution.'" According to Tyler, the annexation of Texas would be a blessing to the whole nation. Because Texas would most likely concentrate its e.fforts on raising cotton, the North and West would find there a market fOl" horses, beef, and wheat. Among the most important of the obvious advantages was security from outside interference with the institution of slavery, especially from British abolition· ists, who were working to get Texas to abolish slavery. -

The Renaissance in Andrew Fuller Studies: a Bibliographic Essay Nathan A

The Renaissance in Andrew Fuller Studies: A Bibliographic Essay Nathan A. Finn INTRODUCTION1 error of his day. In many ways, he was a Baptist ver- n 2007, John Piper gave his customary biograph- sion of Piper’s personal theological hero, Jonathan Iical talk at the annual Desiring God Conference Edwards. Piper’s talk was subsequently published for Pastors. His topic that year was Andrew Fuller as I Will Go Down If You Will Hold the Rope (2012). 2 (1754–1815), a figure considerably less well-known By all appearances, Fuller had finally arrived. The than previous subjects such as momentum had been building for years. Nathan A. Finn is Associate Professor Athanasius, Augustine, Martin Andrew Fuller was the most important Baptist of Historical Theology and Baptist Luther, John Calvin, J. Gresham theologian in the years between the ministries Studies at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary where he Machen, and Martyn Lloyd- of John Gill (1697–1771) and Charles Spurgeon received his Ph.D. and has served on the Jones. In his talk, Piper argued (1834–1892). He was part of a group of like- faculty since 2006. that Fuller played a key role in minded friends that included John Ryland, Jr. bringing theological renewal to (1753–1825), John Sutcliff (1752–1814), Samuel Dr. Finn is the editor of Domestic Slavery: The Correspondence of Richard the British Particular Baptists Pearce (1766–1799), Robert Hall, Jr. (1764– Fuller and Francis Wayland (Mercer in the late eighteenth century. 1831), and William Carey (1761–1834). These University Press, 2008) and Ministry That renewal, in turn, helped men, but especially Fuller himself, emerged as By His Grace and For His Glory: Essays in Honor of Thomas J. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

How Did William Kiffin Join the Baptists?

How did William Kiffin join the Baptists? HE history of the English Particular Baptists before 1644 is a T great deal more difficult to reconstruct in detail than the authors of Baptist textbooks have normally been prepared explicitly to acknowledge. The documents are few, their interpretation is often uncertain and, in addition, some of the very scanty evidence which does exist appears to be in open conflict with the rest. Some of these problems have to be faced in any attempt to disCQver exactly how William Kiffin (1616-1701) came to be, by 1644, the leader of a Baptist congregation. There are two opposing versions of this process. The earlier is Kiffin's own which leaves the clear impression that he joined a congregation of Independent Puritans about 1638 which gradually evolved, under his leadership, into the Baptist church of which he remained pastor until his death. The second account, given by Thomas Crosby in his History of the English Baptists/ suggests that Kiffin first joined an Independent church (per haps that led by Henry Jessey), then joined John Spilsbery's Particular Baptist congregation and eventually, after a disagreement with Spils bery, left that also, presumably to gather his own. It must at once be admitted that there is nothing intrinsically unlikely about either ver sion in a period as turbulent spiritually as politically. Whilst it might at first sight seem that Kiffin's own account is far more likely to be trustworthy both the fact that he wrote at least a quarter of a century after these early events took place and his motive for writing forbid the rejection of Crosby's record without careful discussion.