15 R.T. KENDALL and WESTMINSTER Editor ^

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Carey Conference in Africa

Editorial Bible Conferences News. Reporting is restricted because the political sihiation in Burma is precarious. There is a vast need in the developing Pastors are subject to persecution. The world, Asia, Latin America and Africa for needs in the sub-continent of India are sound theological training. In these areas almost identi cal to those of Africa. It is Bible-beli eving Christians continue to becoming more difficu lt for Chri stian multiply and there are innumerable workers to obtain visas for India and this in digenous pastors who are wi lling to must surely be a matter of prayer. travel long distances and undergo hardship to be able to improve and refine Th e Life and Legacies of Doctor Martyn understanding of the Bible. They hunger Lloyd-Jones to develop their ski ll s in expository preaching and to grow in their grasp of Doctor David Martyn Lloyd-fones died Biblical, Systematic and Historical on St David's Day (l" March) 198 1. He Theology. Areas of acute need are an was born at the end of the reign of Queen understanding of the attributes of God, a Victoria and lived through 29 years of the grip of God's way of salvation in li eu of reign of Queen Eli zabeth II. His life an over-simplified decisionism, the spanned th e two great World Wars. He doch·ine of progressive sanctification, and ministered tlu·ough the years of the great helps and inspiration for godly, economic depression of the 1930s. He disciplined living in the home and at worked in the heart of London when that work. -

Westminster Chapel - What Happened?

Visit our website www.reformation-today.org Editorial comment Foll owin g the expositi on by Spencer C unnah on the role of the pastor whi ch appeared in the last issue (RT 192), Robert Stri vens shows that theology is the driv ing force in the pastor's li fe and how important it is that every pastor be a theologian. But it is not all stud y. The pastor needs to relate to his people and be w ith them by way of hospita lity or by visitation. That subject is addressed in the artic le on visitation . The degree to which writing on visitation has been neglected is illustrated by th e fact that there is onl y one entry fo r it the new 2003 The FINDER (Banner ofTruth 1955-2002, RT 1970- 2002, Westminster Conference 1955-2002). The above emphasis on the pastor as theologian should not detract from the fact that every Christian is a theologian, not in the sense of being a specialist but certainly in the sense of knowing God and be ing proficient in C hri stian truth . Contributors to this issue Robert Strivens practised as a soli citor in London and Brussels for 12 years before training fo r the pastoral ministry at London Theological Seminary ( 1997-99). In 1999, he was call ed to the pastorate of Banbury Evangeli cal Free C hurch, founded 18 years ago. He li ves in Banbury with hi s w ife Sarah and three children, David, Thomas and Danie l. Roger We il has devoted hi s life to visiting and working with pastors in Eastern Europe. -

Sundials, Solar Rays, and St Paul's Cathedral

Extract from: Babylonian London, Nimrod, and the Secret War Against God by Jeremy James, 2014. Sundials, Solar Rays, and St Paul's Cathedral Since London is a Solar City – with St Paul's Cathedral representing the "sun" – we should expect to find evidence of solar rays , the symbolic use of Asherim to depict the radiant, life-sustaining power of the sun. Such a feature would seem to be required by the Babylonian worldview, where Asherim are conceived as conduits of hidden power, visible portals through which the gods radiate their "beneficent" energies into the universe. The spires and towers of 46 churches are aligned with the center of the dome of St Paul's Cathedral, creating 23 "solar rays". I was already familiar with this idea from my research into the monuments of Dublin, where church steeples and other Asherim are aligned in radial fashion around the "sun," the huge modern obelisk known as the Millennium Spire. As it happens, a total of 23 "solar rays" pass through the center of the dome of St Paul's Cathedral, based on the alignment of churches alone . Thus, in the diagram above, two churches sit on each line. If other types of Asherim are included – such as obelisks, monoliths, columns and cemetery chapels – the number is substantially greater. [The 46 churches in question are listed in the table below .] 1 www.zephaniah.eu The churches comprising the 23 "rays" emanating from St Paul's Cathedral 1 St Stephen's, Westbourne Park St Paul's Cathedral St Michael's Cornhill 2 All Souls Langham Place St Paul's Cathedral St Paul's Shadwell -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal "All Who Love Our Blessed Redeemer" Graham, L.A. 2021 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Graham, L. A. (2021). "All Who Love Our Blessed Redeemer": The Catholicity of John Ryland Jr. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT “ALL WHO LOVE OUR BLESSED REDEEMER” The Catholicity of John Ryland Jr ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor of Philosophy aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit Religie en Theologie op dinsdag 19 januari 2021 om 13.45 uur in de online bijeenkomst van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Lon Alton Graham geboren te Longview, Texas, Verenigde Staten promotoren: prof.dr. -

Westminster Pulpit-G Campbell Morgan

Westminster Pulpit-G Campbell Morgan 1. Sermons on Genesis through Nehemiah 2. Sermons on Psalms through Song of Solomon 3. Sermons on Isaiah through Zechariah 4. Sermons on Matthew 5. Sermons on Mark through John 6. Sermons on Acts through Colossians 7. Sermons on 1 Thessalonians through Revelation - - Series on "Problems" The Old Testament Sermons Of G. Campbell Morgan 1915 Who Was G. Campbell Morgan? G. Campbell Morgan was a preacher of the Gospel and teacher of the Bible. Preaching Magazine ranked him # 6 on their list of the Ten Greatest Preachers of the Twentieth Century. Dr. Timothy Warren wrote of him, “G. Campbell Morgan helped influence the shape of evangelical preaching on both sides of the Atlantic.” Though born in England and best known for his two tenures as pastor of Westminster Chapel in London, Campbell Morgan crossed the Atlantic Ocean 54 times in his ministry. He was often called the “Prince of Expositors” for his Bible based preaching. He was without question the most famous evangelical preacher in England, and probably the world, during the first 40 years of the 20th Century. Morgan was an educator when God called him to preach. He applied to become a Methodist preacher in 1888, but was turned down. After preaching his trial sermon to the Methodist Board of Ministry, his examiners rejected his application, saying that his preaching showed no promise. The rejection stung deeply, and Campbell Morgan nearly gave up his calling. That very night he telegraphed his father one word, “Rejected”. But his father replied, “Rejected on earth; Accepted in heaven”. -

18-Fallns.Pdf

Fall 2018 September 1 - November30 CONTENTS Alpha.......................5&22 Prayer............................29 Baptism Class................5 Serve Groups.................13 Calendar.....................8-9 Start Here........................4 Care............................28 Social Media..................12 Christmas....................11 Special Events.................9 College........................21 Staff..............................32 Counseling...................28 Sunday Mornings..........6 -7 Creative Arts...............30 Thanksgiving Events.......11 Family Ministries...... 18-21 Tues Morning Bible.........22 Giving..........................31 Vision Statement.............3 SUNDAY SERVICES Grow Groups...........13-17 Volunteer.......................10 9 & 10:45 AM Job Support...........4 & 28 Wednesday Bible Study..22 Sanctuary Livestream...................12 Weekly Events..................8 Maps......................34-36 Welcome......................2-3 OFFICE HOURS Marriage Preparation...28 What We Believe..............3 Tuesday-Friday Men.............................24 Who We Are..................2 -3 9 AM - 5 PM Men’s Bible Study.........24 Women.................... .22-23 Mentoring....................25 Young Adult...................21 ADDRESS Online Features............12 Worship.........................30 13646 NE 24th Street Operations...................31 Westminster Lang. Acad..25 Bellevue, WA 98005 Outreach.................26-27 Youth Calendar...............20 PHONE (425) 747-1461 FAX (425) 643-7365 Find current -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free

Issue 81: John Newton: Author of “Amazing Grace” John Newton: Did You Know? Interesting and unusual facts about John Newton's life and times Newton the muse Did Newton inspire the writers of Europe's Romantic movement? Various critics have seen him as anticipating Blake's prophetic vision, or as a source for Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" or for episodes in Wordsworth's "Prelude." Man in the middle Even John Wesley recognized the role Newton played in forging a "center" for evangelical Christianity. He wrote to Newton, "You appear to be designed by Divine Providence for an healer of breaches, a reconciler of honest but prejudiced men, and an uniter (happy work!) of the children of God that are needlessly divided from each other." Yes, that's 216 welts When caught attempting to leave the Royal Navy, into which he had been impressed against his will, Newton was whipped 24 times with a cat-o'-nine-tails (similar to the whip in the eighteenth-century scene above). This was actually the lighter punishment for going absent without leave. He could have been hung for desertion. Those … blessed Yankees In June of 1775, after news of the first shots of the War of American Independence broke, Newton's Olney parishioners held an impromptu early-morning prayer meeting. Newton reported to Lord Dartmouth, Olney's Lord of the Manor and Secretary of State for the American Colonies, that between 150 and 200 people turned out at five o'clock in the morning. Newton spoke about the state of the nation, and for an hour the group sang and prayed together. -

Copyright © 2016 Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2016 Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE PREACHING OF JOHN NEWTON (1725-1807): A GOSPEL-CENTRIC, PASTORAL HOMILETIC OF BIBLICAL EXPOSITION __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. May 2016 APPROVAL SHEET THE PREACHING OF JOHN NEWTON (1725-1807): A GOSPEL-CENTRIC, PASTORAL HOMILETIC OF BIBLICAL EXPOSITION Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Hershael W. York (Chair) __________________________________________ Robert A. Vogel __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Angela, whose faithfulness, diligence, and dedicated service to Christ and to others never cease to amaze and inspire me. “Many daughters have done nobly, but you excel them all.” (Prov 31:29) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . vi Chapter 1. THE STUDY OF JOHN NEWTON AND HIS PREACHING . 1 Introduction . 1 Thesis . 6 Background . 7 Methodology . 8 Summary of Content . 11 2. NEWTON’S LIFE AND MINISTRY . 14 Early Years and Life at Sea . 14 Africa and Conversion . 16 Marriage and Call to Ministry . 19 Ministry in Olney and London . 25 Final Years and Death . 33 3. NEWTON’S PREACHING AND THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY . 36 An Overview of Newton’s Preaching . 36 The Eighteenth-Century Context . 54 The Pulpit in Eighteenth-Century England . 58 4. -

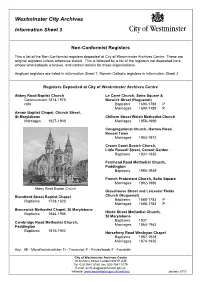

Non-Conformist Registers

Westminster City Archives Information Sheet 3 Non-Conformist Registers This a list of the Non-Conformist registers deposited at City of Westminster Archives Centre. These are original registers unless otherwise stated. This is followed by a list of the registers not deposited here, whose whereabouts is known, and contact details for these organisations. Anglican registers are listed in Information Sheet 1, Roman Catholic registers in Information Sheet 2. Registers Deposited at City of Westminster Archives Centre Abbey Road Baptist Church Le Carré Church, Soho Square & Communicant 1874-1975 Berwick Street (Huguenot) rolls Baptisms 1690-1788 P Marriages 1690-1788 P Aenon Baptist Chapel, Church Street, St Marylebone Chiltern Street Welsh Methodist Church Marriages 1927-1940 Marriages 1956-1999 Congregational Church, Harrow Road, Kensal Town Marriages 1903-1972 Crown Court Scotch Church, Little Russell Street, Covent Garden Baptisms 1831-1835 Fernhead Road Methodist Church, Paddington Baptisms 1885-1949 French Protestant Church, Soho Square Marriages 1992-1996 Abbey Road Baptist Church Glasshouse Street and Leicester Fields Blandford Street Baptist Chapel Church (Huguenot) Baptisms 1728-1820 Baptisms 1688-1783 P Marriages 1688-1783 P Brunswick Methodist Chapel, St Marylebone Hinde Street Methodist Church, Baptisms 1844-1906 St Marylebone Baptisms 1837 Cambridge Road Methodist Church, Marriages 1864-1963 Paddington Baptisms 1876-1922 Horseferry Road Wesleyan Chapel Baptisms 1887-1928 Marriages 1874-1926 Key: Mf - Microfilm/microfiche; Tr - -

Menno Simons

REFORMATION TODAY Ministers (some with their wives) at Perth, 19 September. Conference subject, 'The Primacy of Preaching' (see News) THE CAREY CONFERENCE FOR MINISTERS The Hayes Conference Centre, Swanwick, Derbyshire 4-6 January 1995 - Theme: 'Is Real Revival an Option Today?' DAY 1 Geoff Thomas Powerful Preaching fro m Daniel Rowland to Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones What were the distinctive features of Welsh preaching which God has blessed for over two centuries, which eventually gave Wales the title "Land of Revivals"? Thomas N. Smith The Authenticity of the Gospel Today - I DAY2 Sinclair Ferguson Knowing the Holy Spirit Bob Sheehan The Love of God for Sinners Erroll Hulse The Implications of Revival and Revivalism Today PRAYER AND SHARING Thomas N. Smith The Authenticity of the Gospel Today - 2 DAY3 Sinclair Ferguson Experiencing the Holy Spirit Concluding session to be decided. Dr Mohler has had to postpone his visit to us. We are grateful that pastor Thomas N. Smith of Virginia, whose ministry has been appreciated before at the conference, is able to help us. Details and booking forms available from John Rubens, 22 Leith Road, Darlington, Co. Durham DL3 8BG THE WESTMINSTER CONFERENCE 13 -14 December 1994 Westminster Chapel, Buckingham Gate, LONDON. DAY 1 l. William Tyndale and Justification by Faith - The Answer to Sir Thomas More - Mark De ver 2. The Council of Trent and Modern Views of J us ti fication by Faith - Philip Eveson 3. The Puritan Woman -John Marshall DAY2 4. The Puritan Treatment of Melancholy - Gareth Crossley 5. The Puritans and the Direct Operations of the Spirit - Christopher Bennett 6. -

Sermons and Its

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE EVANGELISTIC PREACHING OF MARTYN LLOYD-JONES WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO HIS ‘ACTS’ SERIES OF SERMONS AND ITS RELEVANCE FOR UK PASTORS TODAY GARY STEWART BENFOLD BSc (Hons), MA DIRECTOR OF STUDIES: Dr Jenny Read-Heimerdinger SECOND SUPERVISOR: Dr Robert Pope In collaboration with Wales Evangelical School of Theology STATEMENT: This research was undertaken under the auspices of the University of Wales: Trinity Saint David and was submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of a Degree of DMin by Research in the School of Theology, Religious and Islamic Studies of the University of Wales. April 2017 Abstract A Critical Evaluation of the Evangelistic Preaching of Martyn Lloyd-Jones with Special Reference to his ‘Acts’ Series of Sermons and its Relevance for UK Pastors Today Abstract The ministry of David Martyn Lloyd-Jones (1899-1981), a leading British preacher within the Reformed tradition, has been a subject of research in the decades since his death. In spite of the importance he himself attached to evangelistic preaching, however, no significant study has been conducted of his own evangelistic preaching. This dissertation explores his weekly evangelistic ministry based on the Book of Acts in the 1960s, his closing years at Westminster Chapel, London. The purpose is to consider the ongoing usefulness, if any, of his practice and method for ministers who stand in the same theological tradition today. The work examines, first, the convictions that drove Lloyd-Jones’ practice, using his published addresses as primary source material. Beyond a summary of his career and his influence (Chapter One), consideration is given to the religious and social context at the time of the Acts sermons, and to its significance for the approach Lloyd-Jones successfully adopted (Chapter Two). -

Lloyd-Jones on Romans

CHAPTER 23 The Apostle and the Doctor: Lloyd-Jones on Romans Stephen Westerholm In a recent review of a volume on modern interpretations of Romans, I. Howard Marshall commented on one notable omission from the discussion: If we ask who has been the most influential interpreter of Romans in the church in the twentieth century, one strong candidate is David Martyn Lloyd-Jones. You do not hear about him in academic circles. Quite simply, he was the finest preacher and expositor of Romans in the evangelical wing of the church, and John Calvin and Martin Luther will have been the major influences upon him. He did not always get it right, but of the breadth of his influence in the U.K. there can be no doubt.1 Lloyd-Jones was minister at Westminster Chapel in London from 1939 until 1968.2 Over the last twelve-and-a-half years of his ministry (October 7, 1955 to March 1, 1968), he preached a series of 372 sermons on Romans on Friday evenings, October to May, to “five or six hundred” eager listeners.3 The series— and his ministry at the Chapel—ended abruptly after a sermon on Romans 14:17 because of ill health, though Lloyd-Jones was able to devote time in his retirement to editing these sermons for publication. After his death in 1981, the work was continued by his wife and daughter, assisted by others; the four- teenth and final volume in the series (on Rom 14:1–17) was published in 2003.4 1 Marshall, Review of Modern Interpretations of Romans.