The Representation of Central-Southern Italian Dialects and African-American Vernacular English in Translation: Issues of Cultural Transfers and National Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language, Culture, and National Identity

Language, Culture, and National Identity BY ERIC HOBSBAWM LANGUAGE, culture, and national identity is the ·title of my pa per, but its central subject is the situation of languages in cul tures, written or spoken languages still being the main medium of these. More specifically, my subject is "multiculturalism" in sofar as this depends on language. "Nations" come into it, since in the states in which we all live political decisions about how and where languages are used for public purposes (for example, in schools) are crucial. And these states are today commonly iden tified with "nations" as in the term United Nations. This is a dan gerous confusion. So let me begin with a few words about it. Since there are hardly any colonies left, practically all of us today live in independent and sovereign states. With the rarest exceptions, even exiles and refugees live in states, though not their own. It is fairly easy to get agreement about what constitutes such a state, at any rate the modern model of it, which has become the template for all new independent political entities since the late eighteenth century. It is a territory, preferably coherent and demarcated by frontier lines from its neighbors, within which all citizens without exception come under the exclusive rule of the territorial government and the rules under which it operates. Against this there is no appeal, except by authoritarian of that government; for even the superiority of European Community law over national law was established only by the decision of the constituent SOCIAL RESEARCH, Vol. -

L'archivio Di Graziadio Isaia Ascoli

Dottorato di ricerca in Storia e Archeologia del Medioevo, Istituzioni e Archivi. Sezione “Istituzioni e Archivi”. Ciclo XXIII. Università di Siena. Progetto di ricerca di SUSANNA PANETTA TITOLO DEL PROGETTO: L’archivio di Graziadio Isaia Ascoli: una documentazione per la storia della cultura e la politica dell’Italia post-unitaria TEMA E OBIETTIVI: Graziadio Isaia Ascoli (1829-1907), insigne linguista di fama internazionale, attento politico, esponente fra i più illustri della comunità ebraica italiana, fu attivo in un periodo chiave per la storia nazionale. Fondatore della linguistica comparata nel nostro paese, fu intellettuale stimato e apprezzato anche Oltralpe. Il suo archivio custodisce la documentazione inerente sia le esperienze private, sia le attività pubbliche: dai primi quaderni di esercitazioni di scrittura, di disegno, agli scritti politici, tutto il materiale strumento della sua produzione scientifica, dalle opere pubblicate a quelle inedite, l’importante carteggio e altri documenti tutti raccolti in 188 unità archivistiche distribuite in 66 scatole e, fin dal 1930, custodito a Roma presso la Biblioteca dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana. L’archivio Ascoli, pur di notevole importanza, è ancora privo di strumenti di corredo completi e funzionali; a rendere più complicata la consultabilità contribuisce il fatto che le circa 10.000 carte costituenti il fondo non sono divise in serie, inoltre l’originaria sedimentazione sembra fondarsi su criteri d’ordinamento variabili (di tipo cronologico, tematico o apparentemente casuale). Relativamente all’archivio Ascoli, il presente progetto si pone come obiettivo la redazione di un inventario analitico e l’individuazione delle serie archivistiche1. L’inventario analitico integrerà i mezzi di corredo parziali e sostituitirà quelli inadeguati attualmente disponibili. -

Dialects, Standards, and Vernaculars

1 Dialects, Standards, and Vernaculars Most of us have had the experience of sitting in a public place and eavesdropping on conversations taking place around the United States. We pretend to be preoccupied, but we can’t seem to help listening. And we form impressions of speakers based not only on the topic of conversation, but on how people are discussing it. In fact, there’s a good chance that the most critical part of our impression comes from how people talk rather than what they are talking about. We judge people’s regional background, social stat us, ethnicity, and a host of other social and personal traits based simply on the kind of language they are using. We may have similar kinds of reactions in telephone conversations, as we try to associate a set of characteristics with an unidentified speaker in order to make claims such as, “It sounds like a salesperson of some type” or “It sounds like the auto mechanic.” In fact, it is surprising how little conversation it takes to draw conclusions about a speaker’s background – a sentence, a phrase, or even a word is often enough to trigger a regional, social, or ethnic classification. Video: What an accent does Assessments of a complex set of social characteristics and personality traits based on language differences are as inevitable as the kinds of judgments we make when we find out where people live, what their occupations are, where they went to school, and who their friends are. Language differences, in fact, may serve as the single most reliable indicator of social position in our society. -

The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 2-2021 The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi Jason Collins The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4143 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SURREALIST VOICE IN MILAN’S ITINERANT POETICS: DELIO TESSA TO FRANCO LOI by JASON M. COLLINS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 i © 2021 JASON M. COLLINS All Rights Reserved ii The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________ ____________Paolo Fasoli___________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _________________ ____________Giancarlo Lombardi_____ Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Paolo Fasoli André Aciman Hermann Haller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins Advisor: Paolo Fasoli Over the course of Italy’s linguistic history, dialect literature has evolved a s a genre unto itself. -

Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions

http://lexikos.journals.ac.za; https://doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1604 Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions: A Slovene–English Case Study Marjeta Vrbinc, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Danko Šipka, School for International Letters and Cultures, Arizona State University, Tempe Campus, USA ([email protected]) and Alenka Vrbinc, School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Abstract: This article presents and discusses the findings of a study conducted with the users of Slovene and American monolingual dictionaries. The aim was to investigate how native speakers of Slovene and American English interpret select normative labels in monolingual dictionaries. The data were obtained by questionnaires developed to elicit monolingual dictionary users' attitudes toward normative labels and the effects the labels have on dictionary users. The results show that a higher level of prescriptivism in the Slovene linguistic culture is reflected in the Slovene respon- dents' perception of the labels (for example, a stronger effect of the normative labels, a higher approval for the claim about usefulness of the labels, a considerably lower general level of accep- tance for the standard language) when compared with the American respondents' perception, since the American linguistic culture tends to be more descriptive. However, users often seek answers to their linguistic questions in dictionaries, which means that they expect at least a certain degree of normativity. Therefore, a balance between descriptive and prescriptive approaches should be found, since both of them affect the users. Keywords: GENERAL MONOLINGUAL DICTIONARY, PRESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVITY, DESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVE LABELS, PRIMARY EXCLUSION LABELS, SECONDARY EXCLUSION LABELS, USE OF LABELS, USEFULNESS OF LABELS, (UN)LABELED ENTRIES Opsomming: Normatiewe etikette in twee leksikografiese tradisies: 'n Sloweens–Engelse gevallestudie. -

Intonation of Sicilian Among Southern Italo-Romance Dialects Valentina De Iacovo, Antonio Romano

Intonation of Sicilian among Southern Italo-romance dialects Valentina De Iacovo, Antonio Romano Laboratorio di Fonetica Sperimentale “A. Genre”, Univ. degli Studi di Torino, Italy [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT At a second stage, we select the most frequent pattern found in the data for each modality (also closest to the Dialects of Italy are a good reference to show how description provided by [10]) and compare it with prosody plays a specific role in terms of diatopic other Southern Italo-romance varieties with the aim variation. Although previous experimental studies of verifying a potential similarity with other Southern have contributed to classify a selection of some and Upper Southern varieties. profiles on the basis of some Italian samples from this region and a detailed description is available for some 2. METHODOLOGY dialects, a reference framework is still missing. In this paper a collection of Southern Italo-romance varieties 2.1. Materials and speakers is presented: based on a dialectometrical approach, For the first experiment, data was part of a more we attempt to illustrate a more detailed classification extensive corpus available online which considers the prosodic proximity between (http://www.lfsag.unito.it/ark/trm_index.html, see Sicilian samples and other dialects belonging to the also [4]). We select 31 out of 40 recordings Upper Southern and Southern dialectal areas. The representing 21 Sicilian dialects (9 of them were results, based on the analysis of various corpora, discarded because their intonation was considered show the presence of different prosodic profiles either too close to Standard Italian or underspecified regarding the Sicilian area and a distinction among in terms of prosodic strength). -

Using Italian

This page intentionally left blank Using Italian This is a guide to Italian usage for students who have already acquired the basics of the language and wish to extend their knowledge. Unlike conventional grammars, it gives special attention to those areas of vocabulary and grammar which cause most difficulty to English speakers. Careful consideration is given throughout to questions of style, register, and politeness which are essential to achieving an appropriate level of formality or informality in writing and speech. The book surveys the contemporary linguistic scene and gives ample space to the new varieties of Italian that are emerging in modern Italy. The influence of the dialects in shaping the development of Italian is also acknowledged. Clear, readable and easy to consult via its two indexes, this is an essential reference for learners seeking access to the finer nuances of the Italian language. j. j. kinder is Associate Professor of Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He has published widely on the Italian language spoken by migrants and their children. v. m. savini is tutor in Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He works as both a tutor and a translator. Companion titles to Using Italian Using French (third edition) Using Italian Synonyms A guide to contemporary usage howard moss and vanna motta r. e. batc h e lor and m. h. of f ord (ISBN 0 521 47506 6 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 64177 2 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 47573 2 paperback) (ISBN 0 521 64593 X paperback) Using French Vocabulary Using Spanish jean h. -

Dialects of Spanish and Portuguese

30 Dialects of Spanish and Portuguese JOHN M. LIPSKI 30.1 Basic Facts 30.1.1 Historical Development Spanish and Portuguese are closely related Ibero‐Romance languages whose origins can be traced to the expansion of the Latin‐speaking Roman Empire to the Iberian Peninsula; the divergence of Spanish and Portuguese began around the ninth century. Starting around 1500, both languages entered a period of global colonial expansion, giving rise to new vari- eties in the Americas and elsewhere. Sources for the development of Spanish and Portuguese include Lloyd (1987), Penny (2000, 2002), and Pharies (2007). Specific to Portuguese are fea- tures such as the retention of the seven‐vowel system of Vulgar Latin, elision of intervocalic /l/ and /n/ and the creation of nasal vowels and diphthongs, the creation of a “personal” infinitive (inflected for person and number), and retention of future subjunctive and pluper- fect indicative tenses. Spanish, essentially evolved from early Castilian and other western Ibero‐Romance dialects, is characterized by loss of Latin word‐initial /f‐/, the diphthongiza- tion of Latin tonic /ɛ/ and /ɔ/, palatalization of initial C + L clusters to /ʎ/, a complex series of changes to the sibilant consonants including devoicing and the shift of /ʃ/ to /x/, and many innovations in the pronominal system. 30.1.2 The Spanish Language Worldwide Reference grammars of Spanish include Bosque (1999a), Butt and Benjamin (2011), and Real Academia Española (2009–2011). The number of native or near‐native Spanish speakers in the world is estimated to be around 500 million. In Europe, Spanish is the official language of Spain, a quasi‐official language of Andorra and the main vernacular language of Gibraltar; it is also spoken in adjacent parts of Morocco and in Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony. -

Composizione Plurilingue Del Territorio Del Friuli Venezia Giulia

COMPOSIZIONE PLURILINGUE DEL TERRITORIO DEL FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA 1. Premessa Istituita nel 1963, la regione autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia non corrisponde affatto ad una unità culturale reale e neppure ad una unità storico- politica, dal momento che l'odierna configurazione istituzionale rispecchia uno stato di cose “amministrativo e non culturale, derivante da successivi e complessi spostamenti dei confini sia nazionali che interni e quindi, in una certa misura, ‘artificiale’, non fondata cioè su una continuità storica”1. Malgrado tale limite, il Friuli Venezia Giulia, in quanto luogo di incontro e di intersezione delle tre grandi civiltà europee - quella latina, quella germanica e quella slava -, rappresenta un’area linguistico-culturale con una propria riconoscibile specificità nella quale, accanto alla lingua italiana (nella sua forma standard e nelle sue varianti regionali), convivono altri idiomi romanzi, germanici e slavi che fanno del territorio regionale un vero e proprio microcosmo plurilingue. Le principali varietà romanze ‘native’ sono rispettivamente il friulano, che rappresenta la variante orientale di un tipo linguistico (il ladino) riconosciuto autonomo a partire da Ascoli (Saggi ladini, 1873), e il veneto, praticato sia nella forma ‘coloniale’ tipica della Venezia Giulia e dei principali centri urbani del Friuli sia sotto forma di adstrato sia infine, ad esempio nelle località lagunari, come parlata di antico insediamento. Per quanto riguarda la componente slavofona, esistono compatti territori di espressione slovena a ridosso del confine nelle province di Trieste e Gorizia oltre a varie comunità disseminate nella provincia di Udine, nelle valli del Natisone (Slavia Veneta) e del Torre e nella Val Resia, nella Val Canale e nel Tarvisiano; isole linguistiche tedescofone infine si annoverano in provincia di Udine a Timau/Tischlbong, nel territorio del comune di Paluzza, e a Sauris/Zahre. -

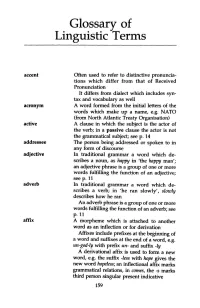

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto -

Debunking Rhaeto-Romance: Synchronic Evidence from Two Peripheral Northern Italian Dialects

A corrigendum relating to this article has been published at ht De Cia, S and Iubini-Hampton, J 2020 Debunking Rhaeto-Romance: Synchronic Evidence from Two Peripheral Northern Italian Dialects. Modern Languages Open, 2020(1): 7 pp. 1–18. DOI: https://doi. org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.309 ARTICLE – LINGUISTICS Debunking Rhaeto-Romance: Synchronic tp://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.358. Evidence from Two Peripheral Northern Italian Dialects Simone De Cia1 and Jessica Iubini-Hampton2 1 University of Manchester, GB 2 University of Liverpool, GB Corresponding author: Jessica Iubini-Hampton ([email protected]) tp://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.358. This paper explores two peripheral Northern Italian dialects (NIDs), namely Lamonat and Frignanese, with respect to their genealogical linguistic classification. The two NIDs exhibit morpho-phonological and morpho-syntactic features that do not fall neatly into the Gallo-Italic sub-classification of Northern Italo-Romance, but resemble some of the core characteristics of the putative Rhaeto-Romance language family. This analysis of Lamonat and Frignanese reveals that their con- servative traits more closely relate to Rhaeto-Romance. The synchronic evidence from the two peripheral NIDs hence supports the argument against the unity and autonomy of Rhaeto-Romance as a language family, whereby the linguistic traits that distinguish Rhaeto-Romance within Northern Italo-Romance consist A corrigendum relating to this article has been published at ht of shared retentions rather than shared innovations, which were once common to virtually all NIDs. In this light, Rhaeto-Romance can be regarded as an array of conservative Gallo-Italic varieties.