Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Download a Reference Grammar of Modern Italian

A REFERENCE GRAMMAR OF MODERN ITALIAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Maiden,Cecilia Robustelli | 512 pages | 01 Jun 2009 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780340913390 | Italian | London, United Kingdom A Reference Grammar of Modern Italian PDF Book This Italian reference grammar provides a comprehensive, accessible and jargon-free guide to the forms and structures of Italian. This rule is not absolute, and some exceptions do exist. Parli inglese? Italian is an official language of Italy and San Marino and is spoken fluently by the majority of the countries' populations. The rediscovery of Dante's De vulgari eloquentia , as well as a renewed interest in linguistics in the 16th century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language. Compared with most other Romance languages, Italian has many inconsistent outcomes, where the same underlying sound produces different results in different words, e. An instance of neuter gender also exists in pronouns of the third person singular. Italian immigrants to South America have also brought a presence of the language to that continent. This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Retrieved 7 August Italian is widely taught in many schools around the world, but rarely as the first foreign language. In linguistic terms, the writing system is close to being a phonemic orthography. For a group composed of boys and girls, ragazzi is the plural, suggesting that -i is a general plural. Book is in Used-Good condition. Story of Language. A history of Western society. It formerly had official status in Albania , Malta , Monaco , Montenegro Kotor , Greece Ionian Islands and Dodecanese and is generally understood in Corsica due to its close relation with the Tuscan-influenced local language and Savoie. -

The Rhaeto-Romance Languages

Romance Linguistics Editorial Statement Routledge publish the Romance Linguistics series under the editorship of MartinS Harris (University of Essex) and Nigel Vincent (University of Manchester). Romance Philogy and General Linguistics have followed sometimes converging sometimes diverging paths over the last century and a half. With the present series we wish to recognise and promote the mutual interaction of the two disciplines. The focus is deliberately wide, seeking to encompass not only work in the phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexis of the Romance languages, but also studies in the history of Romance linguistics and linguistic thought in the Romance cultural area. Some of the volumes will be devoted to particular aspects of individual languages, some will be comparative in nature; some will adopt a synchronic and some a diachronic slant; some will concentrate on linguistic structures, and some will investigate the sociocultural dimensions of language and language use in the Romance-speaking territories. Yet all will endorse the view that a General Linguistics that ignores the always rich and often unique data of Romance is as impoverished as a Romance Philogy that turns its back on the insights of linguistics theory. Other books in the Romance Linguistics series include: Structures and Transformations Christopher J.Pountain Studies in the Romance Verb eds Nigel Vincent and Martin Harris Weakening Processes in the History of Spanish Consonants Raymond Harris-Northall Spanish Word Formation M.F.Lang Tense and Text -

Buccini the Merchants of Genoa and the Diffusion of Southern Italian Pasta Culture in Europe

Anthony Buccini The Merchants of Genoa and the Diffusion of Southern Italian Pasta Culture in Europe Pe-i boccoin boin se fan e questioin. Genoese proverb 1 Introduction In the past several decades it has become received opinion among food scholars that the Arabs played the central rôle in the diffusion of pasta as a common food in Europe and that this development forms part of their putative broad influence on culinary culture in the West during the Middle Ages. This Arab theory of the origins of pasta comes in two versions: the basic version asserts that, while fresh pasta was known in Italy independently of any Arab influence, the development of dried pasta made from durum wheat was a specifically Arab invention and that the main point of its diffusion was Muslim Sicily during the period of the island’s Arabo-Berber occupation which began in the 9th century and ended by stages with the Norman conquest and ‘Latinization’ of the island in the eleventh/twelfth century. The strong version of this theory, increasingly popular these days, goes further and, though conceding possible native European traditions, posits Arabic origins not only for dried pasta but also for the names and origins of virtually all forms of pasta attested in the Middle Ages, albeit without ever providing credible historical and linguistic evidence; Clifford Wright (1999: 618ff.) is the best known proponent of this approach. In AUTHOR 2013 I demonstrated that the commonly held belief that lasagne were an Arab contribution to Italy’s culinary arsenal is untenable and in particular that the Arabic etymology of the word itself, proposed by Rodinson and Vollenweider, is without merit: both word and item are clearly of Italian origin. -

The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 2-2021 The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi Jason Collins The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4143 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SURREALIST VOICE IN MILAN’S ITINERANT POETICS: DELIO TESSA TO FRANCO LOI by JASON M. COLLINS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 i © 2021 JASON M. COLLINS All Rights Reserved ii The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________ ____________Paolo Fasoli___________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _________________ ____________Giancarlo Lombardi_____ Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Paolo Fasoli André Aciman Hermann Haller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins Advisor: Paolo Fasoli Over the course of Italy’s linguistic history, dialect literature has evolved a s a genre unto itself. -

Institutional Repository - Research Portal Dépôt Institutionnel - Portail De La Recherche

Institutional Repository - Research Portal Dépôt Institutionnel - Portail de la Recherche University of Namurresearchportal.unamur.be RESEARCH OUTPUTS / RÉSULTATS DE RECHERCHE Sociolinguistic bibliography of European countries 2014 Darquennes, Jeroen; Held, Gurdrun; Kaderka, Petr; Kellermeier-Rehbein, Birte; Pärn, Hele; Zamora, Francisco; Sandoy, Helge; Ledegen, Gudrun; Oakes, Leigh; Goutsos, Dionysos; Archakis, Argyris; Skelin-Horvath, Anita; Borbély, Anna; Berruto, Gaetano; Kalediene, Laima; Druviete, Ina; Neteland, Randi; Bugarski, Ranko; Troschina, Natalia; Broermann, Marianne ; Gilles, Peter ; Ondrejovic, Slavomir DOI: Author(s)10.1515/soci-2016-0018 - Auteur(s) : Publication date: 2016 Document Version PublicationPublisher's date PDF, - also Date known de aspublication Version of record : Link to publication Citation for pulished version (HARVARD): Darquennes, J, Held, G, Kaderka, P, Kellermeier-Rehbein, B, Pärn, H, Zamora, F, Sandoy, H, Ledegen, G, Oakes, L, Goutsos, D, Archakis, A, Skelin-Horvath, A, Borbély, A, Berruto, G, Kalediene, L, Druviete, I, PermanentNeteland, link R, Bugarski, - Permalien R, Troschina, : N, Broermann, M, Gilles, P & Ondrejovic, S 2016, Sociolinguistic bibliography of European countries 2014: Soziolinguistische Bibliographie europäischer Länder für 2014. de Gruyter, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1515/soci-2016-0018 Rights / License - Licence de droit d’auteur : General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright -

Working Papers in Linguistics and Oriental Studies 1

Universita’ degli Studi di Firenze Dipartimento di Lingue, Letterature e Studi Interculturali Biblioteca di Studi di Filologia Moderna: Collana, Riviste e Laboratorio Quaderni di Linguistica e Studi Orientali Working Papers in Linguistics and Oriental Studies 1 Editor M. Rita Manzini firenze university press 2015 Quaderni di Linguistica e Studi Orientali / Working Papers in Linguistics and Oriental Studies - n. 1, 2015 ISSN 2421-7220 ISBN 978-88-6655-832-3 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/QULSO-2421-7220-1 Direttore Responsabile: Beatrice Töttössy CC 2015 Firenze University Press La rivista è pubblicata on-line ad accesso aperto al seguente indirizzo: www.fupress.com/bsfm-qulso The products of the Publishing Committee of Biblioteca di Studi di Filologia Moderna: Collana, Riviste e Laboratorio (<http://www.lilsi.unifi.it/vp-82-laboratorio-editoriale-open-access-ricerca- formazione-e-produzione.html>) are published with financial support from the Department of Languages, Literatures and Intercultural Studies of the University of Florence, and in accordance with the agreement, dated February 10th 2009 (updated February 19th 2015), between the De- partment, the Open Access Publishing Workshop and Firenze University Press. The Workshop promotes the development of OA publishing and its application in teaching and career advice for undergraduates, graduates, and PhD students in the area of foreign languages and litera- tures, and of social studies, as well as providing training and planning services. The Workshop’s publishing team are responsible for the editorial workflow of all the volumes and journals pub- lished in the Biblioteca di Studi di Filologia Moderna series. QULSO employs the double-blind peer review process. -

Intonation of Sicilian Among Southern Italo-Romance Dialects Valentina De Iacovo, Antonio Romano

Intonation of Sicilian among Southern Italo-romance dialects Valentina De Iacovo, Antonio Romano Laboratorio di Fonetica Sperimentale “A. Genre”, Univ. degli Studi di Torino, Italy [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT At a second stage, we select the most frequent pattern found in the data for each modality (also closest to the Dialects of Italy are a good reference to show how description provided by [10]) and compare it with prosody plays a specific role in terms of diatopic other Southern Italo-romance varieties with the aim variation. Although previous experimental studies of verifying a potential similarity with other Southern have contributed to classify a selection of some and Upper Southern varieties. profiles on the basis of some Italian samples from this region and a detailed description is available for some 2. METHODOLOGY dialects, a reference framework is still missing. In this paper a collection of Southern Italo-romance varieties 2.1. Materials and speakers is presented: based on a dialectometrical approach, For the first experiment, data was part of a more we attempt to illustrate a more detailed classification extensive corpus available online which considers the prosodic proximity between (http://www.lfsag.unito.it/ark/trm_index.html, see Sicilian samples and other dialects belonging to the also [4]). We select 31 out of 40 recordings Upper Southern and Southern dialectal areas. The representing 21 Sicilian dialects (9 of them were results, based on the analysis of various corpora, discarded because their intonation was considered show the presence of different prosodic profiles either too close to Standard Italian or underspecified regarding the Sicilian area and a distinction among in terms of prosodic strength). -

Using Italian

This page intentionally left blank Using Italian This is a guide to Italian usage for students who have already acquired the basics of the language and wish to extend their knowledge. Unlike conventional grammars, it gives special attention to those areas of vocabulary and grammar which cause most difficulty to English speakers. Careful consideration is given throughout to questions of style, register, and politeness which are essential to achieving an appropriate level of formality or informality in writing and speech. The book surveys the contemporary linguistic scene and gives ample space to the new varieties of Italian that are emerging in modern Italy. The influence of the dialects in shaping the development of Italian is also acknowledged. Clear, readable and easy to consult via its two indexes, this is an essential reference for learners seeking access to the finer nuances of the Italian language. j. j. kinder is Associate Professor of Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He has published widely on the Italian language spoken by migrants and their children. v. m. savini is tutor in Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He works as both a tutor and a translator. Companion titles to Using Italian Using French (third edition) Using Italian Synonyms A guide to contemporary usage howard moss and vanna motta r. e. batc h e lor and m. h. of f ord (ISBN 0 521 47506 6 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 64177 2 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 47573 2 paperback) (ISBN 0 521 64593 X paperback) Using French Vocabulary Using Spanish jean h. -

Italian Bookshelf

This page intentionally left blank x . ANNALI D’ITALIANISTICA 37 (2019) Italian Bookshelf www.ibiblio.org/annali Andrea Polegato (California State University, Fresno) Book Review Coordinator of Italian Bookshelf Anthony Nussmeier University of Dallas Editor of Reviews in English Responsible for the Middle Ages Andrea Polegato California State University, Fresno Editor of Reviews in Italian Responsible for the Renaissance Olimpia Pelosi SUNY, Albany Responsible for the 17th, 18th, and 19th Centuries Monica Jansen Utrecht University Responsible for 20th and 21st Centuries Enrico Minardi Arizona State University Responsible for 20th and 21st Centuries Alessandro Grazi Leibniz Institute of European History, Mainz Responsible for Jewish Studies REVIEW ARTICLES by Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University) 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti and Alan R. Perry. Italian Prisoners of War in Pennsylvania, Allies on the Home Front, 1944–1945. Lanham, MD: Fairleigh Dickinson Press, 2016. Pp. 312. 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti e Alan R. Perry. Prigionieri di guerra italiani in Pennsylvania 1944–1945. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2018. Pp. 372. 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti. World War II Italian Prisoners of War in Chambersburg. Charleston: Arcadia, 2017. Pp. 128. Contents . xi GENERAL & MISCELLANEOUS STUDIES 535 Lawrence Baldassaro. Baseball Italian Style: Great Stories Told by Italian American Major Leaguers from Crosetti to Piazza. New York: Sports Publishing, 2018. Pp. 275. (Alan Perry, Gettysburg College) 537 Mario Isnenghi, Thomas Stauder, Lisa Bregantin. Identitätskonflikte und Gedächtniskonstruktionen. Die „Märtyrer des Trentino“ vor, während und nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Cesare Battisti, Fabio Filzi und Damiano Chiesa. Berlin: LIT, 2018. Pp. 402. (Monica Biasiolo, Universität Augsburg) 542 Journal of Italian Translation. Ed. Luigi Bonaffini. -

Raffaello Barbiera Carlo Porta E La Sua Milano

Raffaello Barbiera Carlo Porta e la sua Milano www.liberliber.it Questo e-book è stato realizzato anche grazie al so- stegno di: E-text Web design, Editoria, Multimedia (pubblica il tuo libro, o crea il tuo sito con E-text!) http://www.e-text.it/ QUESTO E-BOOK: TITOLO: Carlo Porta e la sua Milano AUTORE: Barbiera, Raffaello TRADUTTORE: CURATORE: NOTE: Il testo è tratto da una copia in formato im- magine presente sul sito Internet Archive (https://www.archive.org/). Realizzato in collaborazione con il Project Guten- berg (https://www.gutenberg.net/) tramite Distributed proofreaders (https://www.pgdp.net/). CODICE ISBN E-BOOK: n. d. DIRITTI D'AUTORE: no LICENZA: questo testo è distribuito con la licenza specificata al seguente indirizzo Internet: http://www.liberliber.it/online/opere/libri/licenze/ COPERTINA: n. d. TRATTO DA: Carlo Porta e la sua Milano / Raffaello Barbiera - Firenze : G. Barbera, 1921 - XI, 423 p., [1] c. di tav. : ritr. ; 20 cm. 2 CODICE ISBN FONTE: n. d. 1a EDIZIONE ELETTRONICA DEL: 29 maggio 2018 INDICE DI AFFIDABILITÀ: 1 0: affidabilità bassa 1: affidabilità standard 2: affidabilità buona 3: affidabilità ottima SOGGETTO: FIC004000 FICTION / Classici DIGITALIZZAZIONE: Distributed proofreaders, https://www.pgdp.net/ REVISIONE: Claudio Paganelli, [email protected] IMPAGINAZIONE: Claudio Paganelli, [email protected] PUBBLICAZIONE: Claudio Paganelli, [email protected] 3 Liber Liber Se questo libro ti è piaciuto, aiutaci a realizzarne altri. Fai una donazione: http://www.liberliber.it/online/aiuta/. Scopri sul sito Internet di Liber Liber ciò che stiamo realizzando: migliaia di ebook gratuiti in edizione inte- grale, audiolibri, brani musicali con licenza libera, video e tanto altro: http://www.liberliber.it/. -

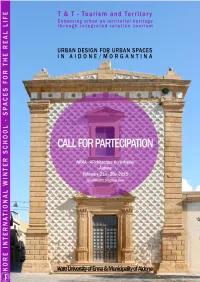

Call for Partecipation.Pdf

The Faculty of Engineering and Architecture at the ARKA Lab in Aidone offers the opportunity of a full- time research and didactic experience in enhancing urban & territorial heritage through Integrated Relational Tourism. An activity focused on the issue of Urban Design for Urban Spaces in Aidone/Morgantina as an opportunity aimed to improve the quality of life so as the local economic development for the communities of the inland rural areas. The Kore International Winter School 2015, represents a continuous of activities as interviews and meetings, workshops and expositions, lectures and site visits that, through 8 full days of common work, should explore problems and hopefully propose a range of visions for the future of the city and of the hinterland of Aidone-Morgantina and its heritage. The Kore International Winter School 2015 includes field trips and guided visits to the study site of Aidone and Morgantina, Piazza Armerina and Villa del Casale, Enna and Pergusa areas as well as social and cultural events. The School activities are articulated on three structural goals, which are: - the activity of scientific and applied Research, implicit in the proposed innovative approach as in the chosen application field; - the integrated project implementation Scenarios, as expected design results by the workshop; - the Training for new needed professionals, important to manage the transition to a different development model from the current one. Official and work languages Official language: English (for meetings, lectures, exibitions, etc.) Work languages: Arabic and Italian (for any other informal relationships!) Short Presentation The Winter School aims to promote a trans-disciplinary and international approach that encourages the development of skills and knowledge in the field of Integrated Tourism managed by the territory through its local actors and resources. -

Milan Celtic in Origin, Milan Was Acquired by Rome in 197 B.C. an Important Center During the Roman Era (Mediolânum Or Mediola

1 Milan Celtic in origin, Milan was acquired by Rome in 197 B.C. An important center during the Roman era (Mediolânum or Mediolanium), and after having declined as a medieval village, it began to prosper as an archiepiscopal and consular town between the tenth and eleventh centuries. It led the struggle of the Italian cities against the Emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa) at Legnano (1176), securing Italian independence in the Peace of Constance (1183), but the commune was undermined by social unrest. During the thirteenth century, the Visconti and Della Torre families fought to impose their lordship or signoria. The Viscontis prevailed, and under their dominion Milan then became the Renaissance ducal power that served as a concrete reference for the fairy-like atmosphere of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Meanwhile, Milan’s archbishopric was influential, and Carlo Borromeo (1538-1584) became a leading figure during the counter-Reformation. Having passed through the rule of the Sforzas (Francesco Sforza ruled until the city was captured by Louis XII of France in 1498) and the domination of the Hapsburgs, which ended in 1713 with the war of the Spanish Succession, Milan saw the establishment of Austrian rule. The enlightened rule of both Hapsburg emperors (Maria Theresa and Joseph II) encouraged the flowering of enlightenment culture, which Lombard reformers such as the Verri brothers, Cesare Beccaria, and the entire group of intellectuals active around the journal Il caffè bequeathed to Milan during the Jacobin and romantic periods. In fact, the city which fascinated Stendhal when he visited it in 1800 as a second lieutenant in the Napoleonic army became, between the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century, a reference point in the cultural and social field.