Danilo Dolci's Sicily

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

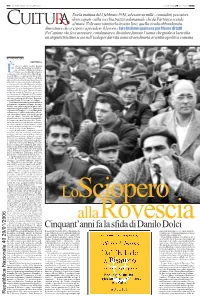

Cinquant'anni Fa La Sfida Di Danilo Dolci

40 LA DOMENICA DI REPUBBLICA DOMENICA 29 GENNAIO 2006 Era la mattina del 2 febbraio 1956, ed erano in mille - contadini, pescatori, disoccupati - sulla vecchia trazzera demaniale che da Partinico scende al mare. Volevano rimetterla in sesto loro, quella strada abbandonata, dimostrare che ci si poteva prendere il lavoro e fare insieme qualcosa per il bene di tutti. Fu l’azione che fece arrestare, condannare e diventare famoso l’uomo che guidava la rivolta: un utopista triestino sceso nell’isola per dar vita a una straordinaria avventura politica e umana ATTILIO BOLZONI PARTINICO ancora senza nome questa strada che dal paese scende fi- no al mare. Ripida nel primo Ètratto, poi va giù dolcemente con le sue curve che sfiorano alberi di pe- sco e di albicocco, passa sotto due ponti, scavalca la ferrovia. L’hanno asfaltata appena una decina di anni fa, prima era un sentiero, una delle tante regie trazze- re borboniche che attraversano la cam- pagna siciliana. È lunga otto chilometri, un giorno forse la chiameranno via dello Sciopero alla Rovescia. Siamo sul ciglio di questa strada di Partinico mezzo se- colo dopo quel 2 febbraio del ‘56, la stia- mo percorrendo sulle tracce di un uomo che sapeva inventare il futuro. Era un ir- regolare Danilo Dolci, uno di confine. Quella mattina erano quasi in mille qui sul sentiero e in mezzo al fango, inverno freddo, era caduta anche la neve sullo spuntone tagliente dello Jato. I pescatori venivano da Trappeto e i contadini dalle valli intorno, c’erano sindacalisti, alleva- tori, tanti disoccupati. E in fondo quegli altri, gli «sbirri» mandati da Palermo, pronti a caricare e a portarseli via quelli lì. -

Società E Cultura 65

Società e Cultura Collana promossa dalla Fondazione di studi storici “Filippo Turati” diretta da Maurizio Degl’Innocenti 65 1 Manica.indd 1 19-11-2010 12:16:48 2 Manica.indd 2 19-11-2010 12:16:48 Giustina Manica 3 Manica.indd 3 19-11-2010 12:16:53 Questo volume è stato pubblicato grazie al contributo di fondi di ricerca del Dipartimento di studi sullo stato dell’Università de- gli Studi di Firenze. © Piero Lacaita Editore - Manduria-Bari-Roma - 2010 Sede legale: Manduria - Vico degli Albanesi, 4 - Tel.-Fax 099/9711124 www.lacaita.com - [email protected] 4 Manica.indd 4 19-11-2010 12:16:54 La mafia non è affatto invincibile; è un fatto uma- no e come tutti i fatti umani ha un inizio e avrà anche una fine. Piuttosto, bisogna rendersi conto che è un fe- nomeno terribilmente serio e molto grave; e che si può vincere non pretendendo l’eroismo da inermi cittadini, ma impegnando in questa battaglia tutte le forze mi- gliori delle istituzioni. Giovanni Falcone La lotta alla mafia deve essere innanzitutto un mo- vimento culturale che abitui tutti a sentire la bellezza del fresco profumo della libertà che si oppone al puzzo del compromesso, dell’indifferenza, della contiguità e quindi della complicità… Paolo Borsellino 5 Manica.indd 5 19-11-2010 12:16:54 6 Manica.indd 6 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Alla mia famiglia 7 Manica.indd 7 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Leggenda Archivio centrale dello stato: Acs Archivio di stato di Palermo: Asp Public record office, Foreign office: Pro, Fo Gabinetto prefettura: Gab. -

Le Parole Di Danilo Dolci Anatomia Lessicale-Concettuale

Biblioteca di Educazione Democratica | 1 Michele Ragone Le parole di Danilo Dolci Anatomia lessicale-concettuale Presentazione di Antonio Vigilante Edizioni del Rosone Biblioteca di Educazione Democratica I Michele Ragone Le parole di Danilo Dolci Anatomia lessicale–concettuale Presentazione di Antonio Vigilante Edizioni del Rosone Quest’opera è rilasciata sotto la licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione-Non commerciale-Condividi allo stesso modo 2.5 Italia. Per leggere una copia della licenza visita il sito web http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/it Tu sei libero: di riprodurre, distribuire, comunicare al pubblico, esporre in pub- blico, rappresentare, eseguire e recitare quest’opera, di modificare quest’opera alle seguenti condizioni: Attribuzione — Devi attribuire la paternità dell’opera nei modi indicati dall’au- tore o da chi ti ha dato l’opera in licenza e in modo tale da non suggerire che essi avallino te o il modo in cui tu usi l’opera. Non commerciale — Non puoi usare quest’opera per fini commerciali. Condividi allo stesso modo — Se alteri o trasformi quest’opera, o se la usi per crearne un’altra, puoi distribuire l’opera risultante solo con una licenza identica o equivalente a questa. Edizione: marzo 2011 Edizioni del Rosone, via Zingarelli, 11 - 71121 Foggia www.edizionidelrosone.it Stampa: Lulu.com ISBN 978-88-97220-19-0 Agropoli, febbraio 2010 Questo lavoro è dedicato agli Amici che nel ricordo di Danilo continuano un dialogo mai interrotto. A loro tutti pure sono debitore. Presentazione Dopo decenni di un oblio che dice molto sul degrado morale e civile di questo paese cominciano ad avvertirsi i primi segni di una riscoperta dell'opera di Danilo Dolci. -

The Inventory of the Danilo Dolci Collection #824

The Inventory of the Danilo Dolci Collection #824 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center DOLCI, DANILO #824 April 1983-Nov. 1984 I. MANUSCRIPT CREATURA DI CREATURE. Poems 1949-1980. New edition, revised and enlarged. 1982. TypescriptJ typescript-mimeo., and printed tearsheets, without corrections. ca. 310 p. on ca. 155 leaves. (#1) II. CORRESPONDENCE A. Letters 12.Y. DD to various persons, Arranged chronologically . 1958-1982, ca. 2000 letters Box 1-4 [1958-1962, B 1, 1963-1968, B. 2; 1969-1973, B.3; 1974-1982, B. 4f B. Letters from the following to DD: (Each folder contains DD's carbons and occasionally other items as well,) Box 4 Chavez, Cesar E. to Mrs. John E. Bailey, TLS photocopy July 29, 1969. (#10) Cousins, Norman (#11) 1966-1972. 11 TLS, 2 cards. Day, Dorothy (#12) 7 ALS, March 28, May 4, 1968 Friedmann, Georges (#13) 1960-1973. 19 TLS, 4 ALS, 2 postcards, 2 misc, Fromm, Erich. (#14) 1963-1980. 15 TLS, 1 ALS, 2 CTL, 5 memos, 1 telegram, 1 TLS photocopy. Giulo Einauid: Editore, S.p,A. (#15) 1956-1961. 5 TLS. Huxley, Aldous (#16) ALS, Oct. 16, 1960 Introduction to book by DD, carbon typescript; 6 p, Huxley, Laura (#16) ALS, Feb, 6, 1961. 1 Box 4 Klineberg, Otto (#17) 1969-1983. 13 TLS, 7 ALS, 1 misc. Luzi, Mario (#18) 2 ALS, 1977 "Incontro Con La Poesia Di Danilo", with holograph corr.; 4 p. type. mimeo., without corr. 4 p. in 2 leaves. "Restorando Su Danilo," typescript with holograph corr. 4 p.; typescript mimeo with holograph corr.; 4 p. -

Antimafia Cooperatives: Land, Law, Labour and Moralities in a Changing Sicily

ANTIMAFIA COOPERATIVES: LAND, LAW, LABOUR AND MORALITIES IN A CHANGING SICILY THEODOROS RAKOPOULOS Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology Goldsmiths College, University of London DECLARATION I DECLARE AS FOLLOWS: I authorise that the thesis presented by me for examination of the above Research Degrees, if a degree is awarded, be deposited as a print copy in the library and as an electronic version in GRO subject to the conditions set below. I understand that in the event of my thesis being not approved by the examiners, or being referred, would make this declaration void. I am the author or co-author and owner of the copyright in the thesis and/or have the authority on behalf of the author or authors to make this agreement and grant Goldsmiths and the British Library a licence to make available the Work in digitised format through GRO and the EThOS system for the purpose of non-commercial research, private study, criticism, review and news reporting, illustration for teaching, and/or other educational purposes in electronic or print form. That I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the Work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. [If in doubt please contact [email protected].] Rights granted to GRO, EThOS and the user of the thesis through this agreement are entirely non-exclusive and royalty free. I retain all rights in the Work in its present version or future versions. -

Avvocati,Ultimatumalsottosegretariotaormina

lire 11.500 (euro 5,93 euro) ARRETRATI L IRE 3.000 – EURO 1.55 anno 78 n.198 domenica 14 ottobre 2001 lire 1.500 (euro 0.77) - www.unita.it SPEDIZ. IN ABBON. POST. 45\% l’Unità + videocassetta “Genova. Per noi.” ART. 2 COMMA 20/B LEGGE 662/96 – FILIALE DI ROMA Il 16 ottobre 1943 nelle case a morire 1022 italiani e vecchi. Responsabili sono di Roma sono stati di religione ebraica, stati soldati nazisti, cercati, catturati e portati donne uomini, bambini militi fascisti e il silenzio. Il Pentagono ammette: ci sono vittime civili Gli Usa parlano di «errore» durante i bombardamenti di Kabul: colpito un quartiere Si allenta la stretta in Medio Oriente: Sharon trattiene le truppe, Arafat incontra Blair Le vittime civili ci sono. Lo ammette il Pentagono che parla dell’«errore» di LA PACE una bomba «intelligente»: invece di col- PRIGIONIERI pire l’aeroporto di Kabul s’è schiantata su un quartiere della città. Quanti mor- DEL COMINCIA ti? Non si sa. Probabilmente tanti. E i bombardamenti continuano: abbiamo PRIMA distrutto tutte le basi di Bin Laden, ha SILENZIO detto Bush lasciando presagire un immi- Furio Colombo nente attacco da terra. I taleban non don Roberto Sardelli s’arrendono. Intanto in Medio Oriente si apre un piccolissimo spiraglio. Dopo a sera del 10 ottobre Rai 3 ha trasmesso un le pressioni Usa, Sharon ordina ai suoi ulla è più pericoloso per documentario su Gino Strada. Molti ricorde- militari di allentare la stretta; Arafat do- l'avvenire del mondo, e L ranno questo nome. È il «medico con le idee mani volerà a Londra per incontrare Bla- «N del resto nulla è meno fon- confuse» di cui ha parlato imprudentemente Berlu- ir. -

Rapporto Di Attività Assemblea Dei Soci 2012

ASSEMBLEA DEI SOCI Mirandola 22 settembre 2012 Gruppo di antifascisti della Bassa modenese, Mirandola 15 ottobre 1946 Premessa C’è un filo conduttore neppure troppo nascosto nelle pagine di questo Programma 2012-2013: l'immanenza della crisi economico-finanziaria che, nel determinare una complessiva contrazione delle risorse, pubbliche e private, disponibili, consegna a tutti noi il frutto avariato di una generale delegittimazione sociale dell’attività scientifica e culturale, in quanto “costosa” e, almeno nel breve, “improduttiva”. L’Istituto storico di Modena – se ne accorgerà chi condurrà, in parallelo alla lettura del Programma, la disamina del Rapporto di Attività e del relativo Resoconto – sta rispondendo bene, in termini quantitativi e qualitativi, ai morsi della crisi. Possiamo dire, con certezza mista ad orgoglio, che il capitale di professionalità e competenze accumulato e accresciuto negli anni precedenti ci sta consentendo di mantenere invariati, o addirittura di accrescere, i livelli di intervento sul tessuto territoriale modenese. Ma l’incertezza sulle risorse, che fa sì che una parte molto significativa del lavoro svolto in Istituto e dall’Istituto sia condotto ormai su basi volontarie (con tutti i pro ma anche i contro che ne conseguono), impedisce lo sguardo lungo di cui avrebbe bisogno una programmazione integrata di tutti i settori, che volesse tenere insieme potenziamento dei servizi e delle dotazioni documentali, consolidamento della ricerca scientifica e dell’attività editoriale, ampliamento delle attività di divulgazione -

Dipartimento Di Scienze Politiche Cattedra Di Analisi E Valutazione Delle Politiche Pubbliche

Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche Cattedra di Analisi e Valutazione delle Politiche pubbliche L’ITALIA DELLA MAFIA E DELL’ANTIMAFIA. ISTITUZIONI E POLITICHE PUBBLICHE ATTUATE CONTRO LA CRIMINALITÀ ORGANIZZATA RELATORE Prof. Antonio La Spina CANDIDATO Giuliana Roda Matr. 628202 CORRELATORE Prof. Mattia Guidi Anno accademico: 2016/2017 1 INDICE Introduzione Capitolo 1 - La mafia in Italia 1.1 Cos’è la mafia. Il processo di riconoscimento del fenomeno mafioso dal diciannovesimo secolo al maxiprocesso. 1.1.1 La mafia e la sua primitiva percezione 1.1.2 La categorizzazione giuridica del fenomeno mafioso, grazie all’opera di svelamento del primo pool antimafia 1.1.3 Il contributo dei pentiti e del maxiprocesso nella conoscenza del fenomeno 1.2 Tratti distintivi e caratteristiche generali delle tre maggiori organizzazioni mafiose italiane. 1.2.1 La mafia come burocrazia professionale: peculiarità e debolezze 1.2.2 Cosa nostra 1.2.3‘Ndrangheta 1.2.4 Camorra 1.3 L’altra faccia del fenomeno: il problema della corruzione. 1.3.1 Il rapporto corruttivo-collusivo tra mafioso e corrotto 1.3.2 La direzione presa per contrastare la corruzione: conoscenza e repressione del fenomeno Capitolo 2 - La realtà italiana della lotta alla mafia 2.1 Che cos’è l’antimafia. 2.1.1 Le due facce della lotta alla mafia 2.2.2 Fasi storiche del movimento antimafia 2 2.2 Analisi e classificazione delle politiche antimafia. 2.2.1 Le politiche antimafia dirette 2.2.2 Le politiche antimafia indirette 2.2.3 Ulteriori categorizzazioni di politiche antimafia 2.3 Le istituzioni antimafia italiane. -

L'sos Di 50 Anni Fa: Così Danilo Dolci Inventò La Radio Libera | Rep

25/3/2020 L'Sos di 50 anni fa: così Danilo Dolci inventò la radio libera | Rep new HOMEPAGE PER TE PArUoDfiIlOo Esci Locali Palermo L'Sos di 50 anni fa: così Danilo Dolci inventò la radio libera 25 MARZO 2020 Il 25 marzo 1970 due collaboratori del sociologo trasmisero da Partinico, in provincia di Palermo, il grido di protesta della Sicilia più povera. Furono bloccati dopo 26 ore DI LUCIO LUCA 4 / 5 CONDIVIDI https://rep.repubblica.it/pwa/locali/2020/03/25/news/l_sos_di_50_anni_fa_cosi_danilo_dolci_invento_la_radio_libera-252262144/#success=true 1/7 25/3/2020 L'Sos di 50 anni fa: così Danilo Dolci inventò la radio libera | Rep new HOMEPAGE PER TE AUDIO “Sos, Sos... siamo i poveri cristi della Sicilia occidentale e questa è la radio della nuova resistenza. Qui si sta morendo…». Il 25 marzo del 1970 - sì esattamente cinquant’anni fa - furono in pochi, anzi pochissimi, ad ascoltare il messaggio disperato lanciato dai 98,5 megahertz della modulazione di frequenza e sui 20.10 delle onde corte. Pochi all’inizio, alle 17,30 di quel pomeriggio rimasto nella memoria, ma sempre di più, una Valle intera, durante le 26 ore di vita della prima radio locale italiana della storia: la Radio Sicilia Libera ispirata da Danilo Dolci. E per l’occasione si moltiplicano le iniziative: Navarra Editore (www.navarraeditore.it) regala l’ebook “Danilo Dolci. La radio dei poveri cristi” curato da Salvo Vitale e Guido Orlando. Radio 100 Passi e il circuito 100 passi medianetwork (radio100passi.net) che riunisce emittenti su tutto il territorio nazionale, ricorderà quell’esperienza riproponendo ampi stralci originali di quella trasmissione, l’intervista a Pino Lombardo e ad Amico Dolci, figlio di Danilo. -

A Socio-Economic Study of the Camorra Through Journalism

A SOCIO-ECONOMIC STUDY OF THE CAMORRA THROUGH JOURNALISM, RELIGION AND FILM by ROBERT SHELTON BELLEW (under the direction of Thomas E. Peterson) ABSTRACT This dissertation is a socio-economic study of the Camorra as portrayed through Roberto Saviano‘s book Gomorra: Viaggio nell'impero economico e nel sogno di dominio della Camorra and Matteo Garrone‘s film, Gomorra. It is difficult to classify Saviano‘s book. Some scholars have labeled Gomorra a ―docufiction‖, suggesting that Saviano took poetic freedoms with his first-person triune accounts. He employs a prose and news reporting style to narrate the story of the Camorra exposing its territory and business connections. The crime organization is studied through Italian journalism, globalized economics, eschatology and neorealistic film. In addition to igniting a cultural debate, Saviano‘s book has fomented a scholarly consideration on the innovativeness of his narrative style. Wu Ming 1 and Alessandro Dal Lago epitomize the two opposing literary camps. Saviano was not yet a licensed reporter when he wrote the book. Unlike the tradition of news reporting in the United States, Italy does not have an established school for professional journalism instruction. In fact, the majority of Italy‘s leading journalists are writers or politicians by trade who have gravitated into the realm of news reporting. There is a heavy literary influence in Italian journalism that would be viewed as too biased for Anglo- American journalists. Yet, this style of writing has produced excellent material for a rich literary production that can be called engagé or political literature. A study of Gomorra will provide information about the impact of the book on current Italian journalism. -

LA RADIO COME STRUMENTO DELLA LOTTA ALLA MAFIA. NOTE DI RICERCA Giulia Pacchiarini

La ricerca 3 LA RADIO COME STRUMENTO DELLA LOTTA ALLA MAFIA. NOTE DI RICERCA Giulia Pacchiarini Title: The radio as a tool in the fight against the mafia. Research notes Abstract This article analyses the role of the radio in the fight against the mafia, highlighting the technical and communicative qualities of the medium and describing its possible uses in anti-mafia projects. The research has been conducted through the selection of different sources and the collection of interviews with exponents of the radio scene. It examines and compares historical cases, the most recent experiments and assesses future projects. Key words: Organised crime; mafia; radio; Danilo Dolci; Peppino Impastato L’articolo analizza il ruolo della radio all’interno della lotta alla mafia, evidenziando le qualità tecniche e comunicative del mezzo e descrivendone i possibili impieghi in progetti antimafia. La ricerca, condotta attraverso la selezione di diverse fonti bibliografiche e la raccolta di interviste a esponenti dell’attuale panorama radiofonico, prende in esame e confronta casi storici, le sperimentazioni più recenti e valuta progetti futuri. Parole chiave: Criminalità organizzata; mafia; radio; Danilo Dolci; Peppino Impastato 85 Cross Vol.6 N°1 (2020) - DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13130/cross-13617 La ricerca 3 Introduzione “Dobbiamo domandarci e risponderci con sicurezza, se esiste alcun mezzo [...] che ci permetta di raggiungere ogni individuo con la massima economia di tempo […], persone e denaro. È evidente che non c’è alcun mezzo tra quelli per ora a noi disponibili, che risponda a questi requisiti, migliore della radio.”1 Così scriveva Danilo Dolci, nel 1970, a Partinico, piccolo comune della Sicilia Occidentale. -

“Sviluppo Delle Competenze Negli Educatori Di Adulti”

“Sviluppo delle competenze negli educatori di adulti” Manuale di formazione con lavoro autonomo e di gruppo EDEC: Rafforzare e sviluppare le competenze degli educatori di adulti Numero del progetto: 2018-1-PL01-KA204-050789 Risultato 2: "Pacchetto di formazione" Autori: Grażyna Knitter, Izabela Mleczko, Simon Dawson, Katarzyna Jaszczuk, Alessandro La Pegna, Alberto Biondo Partner: Fundacja Innowacja i Wiedza (Polonia) Centro Per Lo Sviluppo Creativo Danilo Dolci Onlus Associazione (Italia) Kuratorium Oświaty w Warszawie (Polonia) Sysco Business Skills Academy (Regno Unito)) The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 2 Indice INTRODUZIONE 5 1. MODULO FORMATIVO SULLE COMPETENZE COMUNICATIVE RIVOLTO A EDUCATORI ADULTI 9 CSC- CENTRO PER LO SVILUPPO CREATIVO DANILO DOLCI A cura di Alberto Biondo, Alessandro La Pegna Modulo formativo sulle competenze comunicative rivolto a educatori adulti 1.1 Informazioni di carattere generale sulla comunicazione 9 1.2 Definizioni 10 1.3 Perché le competenze comunicative sono così importanti 12 1.4 Risultati di apprendimento per i/le consulenti educativi/e 13 1.5 Attività didattiche 13 1.6 Strumenti di valutazione 35 1.7 Bibliografia 37 1.8 Programma della sessione (8 ore) 38 2. MODULO FORMATIVO SULLA CREAZIONE DI UN BUON RAPPORTO CON L’UTENTE 39 FOUNDATION OF INNOVATION AND KNOWLEDGE A cura di Grażyna Knitter Modulo formativo sulla creazione di un buon rapporto con l’utente 2.1. Informazioni di carattere generale 39 2.2 Definizioni 41 2.3 Perché è importante instaurare un buon rapporto? 45 2.4 Obiettivi di apprendimento per i/le discenti adulti 49 2.5 Attività didattiche * (esercizi, casi studio) * le attività proposte possono anche essere utilizzate ai fini della crescita personale.