A Socio-Economic Study of the Camorra Through Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Condannati Per Camorra, Scarcerati Di Fabio Postiglione SENTENZA SALVATORE D’ABUNDO E GENNARO ESPOSITO

mercoledì 30 marzo 2011 CRONACA DI NAPOLI 3 IL RIESAME GENNARO FERRO, FRATELLO DEL CAPOCLAN GAETANO BENEDUCE, A CASA PER MOTIVI DI SALUTE Traffico di sostanze stupefacenti, ottiene i domiciliari Tre perizie, una lotta estenuante al Riesame e alla fine la decisione di dell’operazione “Penelope” portata a termine dai carabinieri del concedere gli arresti domiciliari nonostante le gravi accuse: comando provinciale di Napoli e della compagnia di Pozzuoli contro associazione a delinquere finalizzata al traffico di droga aggravata dal affiliati al clan Beneduce-Longobardi. Associazione mafiosa, estorsioni, metodo mafioso. Si tratta di Gennaro Ferro, fratello del capoclan detenzione di armi, tentato omicidi sono i reati contestati a vario titolo Gaetano Beneduce, 60 anni, considerato capo della cosca di Pozzuoli. I ai destinatari dei provvedimenti emessi su richiesta dei pm della Dda di difensori di Ferro, Bruno Carafa e Domenico De Rosa, sono riusciti a Napoli Antonello Ardituro, Gloria Sanseverino e Raffaella Capasso. dimostrare che il loro assistito era assolutamente incompatibile con il L’operazione rappresenta il completamento di una indagine che nel regime carcerario. E così alla fine ci sono riusciti a botta di perizie, ben 2003 portò all'arresto di 40 esponenti della cosca per estorsioni al tre che alla fine hanno dato ragione alla loro tesi. Ferro fu arrestato mercato ittico di Pozzuoli. Sono coinvolti esponenti delle due “famiglie” nella retata che il 24 giugno portò all’azzeramento della cosca che ha che presero il sopravvento nell'area flegrea nel 1997 a conclusione di un terrorizzato per mesi, per anni commercianti e residente della zona sanguinoso scontro con i rivali del clan Sebastiano-Bellofiore. -

English Extension I

ENGLISH EXTENSION I Crime Genre Essay: “Genre sets a framework of conventions. How useful is it to understand texts in terms of genre? Are texts more engaging when they conform to the conventions, or when they challenge and play with conventions?” “Genres offer an important way of framing texts which assists comprehension. Genre knowledge orientates competent readers of the genre towards appropriate attitudes, assumptions and expectations about a text which are useful in making sense of it. Indeed, one way of defining genre is as a ‘set of expectations.’” (Neale, 1980) The crime fiction genre, which began during the Victorian Era, has adapted over time to fit societal expectations, changing as manner of engaging an audience. Victorian text The Manor House Mystery by J.S. Fletcher may be classified as an archetypal crime fiction text, conforming to conventions whilst The Skull beneath the Skin by P.D. James, The Real Inspector Hound by Tom Stoppard and Capote directed by Bennet Miller challenge and subvert conventions. The altering of conventions is an engaging element of modern crime fiction, and has somewhat, become a convention itself. Genre, Roland Barthes argues, is “a set of constitutive conventions and codes, altering from age to age, but shared by a kind of implicit contract between writer and reader” thus meaning it is “ultimately an abstract conception rather than something that exists empirically in the world.”(Jane Feuer, 1992) The classification of literary works is shaped – and shapes – culture, attitude and societal influence. The crime fiction genre evolved following the Industrial Revolution when anxiety grew within the expanding cities about the frequency of criminal activity. -

Matteo Garrone's Gomorrah.” Master’S Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2010

http://www.gendersexualityitaly.com g/s/i is an annual peer-reviewed journal which publishes research on gendered identities and the ways they intersect with and produce Italian politics, culture, and society by way of a variety of cultural productions, discourses, and practices spanning historical, social, and geopolitical boundaries. Title: Matteo Garrone’s Gomorra: A Politically Incorrect Use of Neapolitan Identities and Queer Masculinities? Journal Issue: gender/sexuality/italy, 2 (2015) Author: Marcello Messina, Universidade Federal do Acre Publication date: July 2015 Publication info: gender/sexuality/Italy, “Open Contributions” Permalink: http://www.gendersexualityitaly.com/matteo-garrones-gomorra/ Author Bio: Marcello Messina is Assistant Professor at the Universidade Federal do Acre, Brazil. He is recipient of the PNPD post-doctoral bursary from CAPES (Brazil) and of the Endeavour Research Fellowship (Australia – Macquarie University). He is also active as a composer and musicologist. Abstract: Taking as a starting point John Champagne’s recent argument about the queer representations of Italian masculinity contained in Garrone’s Gomorra, this paper aims to connect the queer masculinity of the film’s characters with the negative judgement on their lives and actions suggested by the film. In particular, it will be argued that queerness is used alongside the Neapolitan- ness of the characters to portray them as Others, in order to alienate the audience from them. In other words, it will be suggested that the film does not celebrate the queerness of the characters, but uses it as a means to portray them as deviant to a non-Neapolitan, heterosexual audience. Copyright Information g/s/i is published online and is an open-access journal. -

Ercolano, Naples

University of Bath PHD Civil society and the anti-pizzo movement: the case of Ercolano, Naples Bowkett, Chris Award date: 2017 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Civil society and the anti-pizzo movement: the case of Ercolano, Naples Christopher Bowkett A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies September 2017 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis/portfolio rests with the author and copyright of any previously published materials included may rest with third parties. A copy of this thesis/portfolio has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it understands that they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author or other copyright owners, as applicable. -

PHILOSOPHIES of CRIME FICTION by JOSEF HOFFMANN Translated by Carolyn Kelly, Nadia Majid & Johanna Da Rocha Abreu NEW TITLE

PHILOSOPHIES OF CRIME FICTION BY JOSEF HOFFMANN Translated By Carolyn Kelly, Nadia Majid & Johanna da Rocha Abreu NEW TITLE MARKETING: A groundbreaking book from an internationally respected writer/academic th Pub. date: 25 July 2013 who has a deep and unique expertise on crime fiction Price: £16.99 Hoffmann references a who’s who of top crime writers – Conan Doyle, ISBN13: 978-1-84344-139-7 Chesterton, Hammett, Camus, Borges, Christie, Chandler, Lewis Binding: Paperback Provides an utterly fresh understanding of the philosophical ideas which Format: Royal(234 x 156mm) underpin crime fiction Extent: 192pp Shows how the insights supplied by great crime writers enable key Rights: World philosophical ideas to be appreciated by a wide audience Market Confirms how much more accessible are crime writers than their philosophical None Restrictions: counterparts – and successful at putting across tenets of philosophy Philosophy / Literary Market: A book for students of philosophy of all ages – and for all crime fiction Theory / Crime Fiction devotees BIC code: HPX / DSA /FF MARKET: Rpt. Code: NP Popular philosophy, Literary Theory, Crime Fiction DESCRIPTION: 'More wisdom is contained in the best crime fiction than in conventional philosophical essays' - Wittgenstein For a review copy, to arrange an author Philosophies of Crime Fiction provides a considered analysis of the philosophical ideas interview or for further information, to be found in crime literature - both hidden and explicit. Josef Hoffmann ranges please contact: Alexandra Bolton expertly across influences and inspirations in crime writing with a stellar cast including +44 (0) 1582 766 348 Conan Doyle, G K Chesterton, Dashiell Hammett, Albert Camus, Borges, Agatha +44 (0) 7824 646 881 Christie, Raymond Chandler and Ted Lewis. -

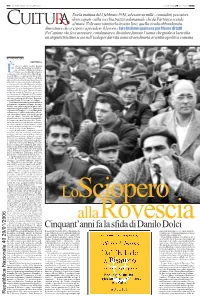

Cinquant'anni Fa La Sfida Di Danilo Dolci

40 LA DOMENICA DI REPUBBLICA DOMENICA 29 GENNAIO 2006 Era la mattina del 2 febbraio 1956, ed erano in mille - contadini, pescatori, disoccupati - sulla vecchia trazzera demaniale che da Partinico scende al mare. Volevano rimetterla in sesto loro, quella strada abbandonata, dimostrare che ci si poteva prendere il lavoro e fare insieme qualcosa per il bene di tutti. Fu l’azione che fece arrestare, condannare e diventare famoso l’uomo che guidava la rivolta: un utopista triestino sceso nell’isola per dar vita a una straordinaria avventura politica e umana ATTILIO BOLZONI PARTINICO ancora senza nome questa strada che dal paese scende fi- no al mare. Ripida nel primo Ètratto, poi va giù dolcemente con le sue curve che sfiorano alberi di pe- sco e di albicocco, passa sotto due ponti, scavalca la ferrovia. L’hanno asfaltata appena una decina di anni fa, prima era un sentiero, una delle tante regie trazze- re borboniche che attraversano la cam- pagna siciliana. È lunga otto chilometri, un giorno forse la chiameranno via dello Sciopero alla Rovescia. Siamo sul ciglio di questa strada di Partinico mezzo se- colo dopo quel 2 febbraio del ‘56, la stia- mo percorrendo sulle tracce di un uomo che sapeva inventare il futuro. Era un ir- regolare Danilo Dolci, uno di confine. Quella mattina erano quasi in mille qui sul sentiero e in mezzo al fango, inverno freddo, era caduta anche la neve sullo spuntone tagliente dello Jato. I pescatori venivano da Trappeto e i contadini dalle valli intorno, c’erano sindacalisti, alleva- tori, tanti disoccupati. E in fondo quegli altri, gli «sbirri» mandati da Palermo, pronti a caricare e a portarseli via quelli lì. -

Investigating Italy's Past Through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and Tv

INVESTIGATING ITALY’S PAST THROUGH HISTORICAL CRIME FICTION, FILMS, AND TV SERIES Murder in the Age of Chaos B P ITALIAN AND ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES AND ITALIAN ITALIAN Italian and Italian American Studies Series Editor Stanislao G. Pugliese Hofstra University Hempstead , New York, USA Aims of the Series This series brings the latest scholarship in Italian and Italian American history, literature, cinema, and cultural studies to a large audience of spe- cialists, general readers, and students. Featuring works on modern Italy (Renaissance to the present) and Italian American culture and society by established scholars as well as new voices, it has been a longstanding force in shaping the evolving fi elds of Italian and Italian American Studies by re-emphasizing their connection to one another. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14835 Barbara Pezzotti Investigating Italy’s Past through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and TV Series Murder in the Age of Chaos Barbara Pezzotti Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand Italian and Italian American Studies ISBN 978-1-137-60310-4 ISBN 978-1-349-94908-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-349-94908-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016948747 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Iovino, Serenella. "Bodies of Naples: a Journey in the Landscapes of Porosity." Ecocriticism and Italy: Ecology, Resistance, and Liberation

Iovino, Serenella. "Bodies of Naples: A Journey in the Landscapes of Porosity." Ecocriticism and Italy: Ecology, Resistance, and Liberation. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 13–46. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219488.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 17:51 UTC. Copyright © Serenella Iovino 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 Bodies of Naples A Journey in the Landscapes of Porosity In the heart of the city of Naples there is a place with a curious name: Largo Corpo di Napoli. This little square opens up like an oyster at a point where the decumani, the Greek main streets, become a tangle of narrow medieval lanes and heavy gray-and-white buildings. Like an oyster, this square has a pearl: An ancient statue of the Nile, popularly known as Corpo di Napoli, the body of Naples. The story of this statue is peculiar. Dating back to the second or third centuries, when it was erected to mark the presence of an Egyptian colony in the city, the statue disappeared for a long time and was rediscovered in the twelfth century. Its head was missing, and the presence of children lying at its breasts led people to believe that it represented Parthenope, the virgin nymph to whom the foundation of the city is mythically attributed. In 1657 the statue was restored, and a more suitable male head made it clear that the reclining figure symbolized the Egyptian river and the children personifications of its tributaries. -

Feminism & Philosophy Vol.5 No.1

APA Newsletters Volume 05, Number 1 Fall 2005 NEWSLETTER ON FEMINISM AND PHILOSOPHY FROM THE EDITOR, SALLY J. SCHOLZ NEWS FROM THE COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN, ROSEMARIE TONG ARTICLES MARILYN FISCHER “Feminism and the Art of Interpretation: Or, Reading the First Wave to Think about the Second and Third Waves” JENNIFER PURVIS “A ‘Time’ for Change: Negotiating the Space of a Third Wave Political Moment” LAURIE CALHOUN “Feminism is a Humanism” LOUISE ANTONY “When is Philosophy Feminist?” ANN FERGUSON “Is Feminist Philosophy Still Philosophy?” OFELIA SCHUTTE “Feminist Ethics and Transnational Injustice: Two Methodological Suggestions” JEFFREY A. GAUTHIER “Feminism and Philosophy: Getting It and Getting It Right” SARA BEARDSWORTH “A French Feminism” © 2005 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 BOOK REVIEWS Robin Fiore and Hilde Lindemann Nelson: Recognition, Responsibility, and Rights: Feminist Ethics and Social Theory REVIEWED BY CHRISTINE M. KOGGEL Diana Tietjens Meyers: Being Yourself: Essays on Identity, Action, and Social Life REVIEWED BY CHERYL L. HUGHES Beth Kiyoko Jamieson: Real Choices: Feminism, Freedom, and the Limits of the Law REVIEWED BY ZAHRA MEGHANI Alan Soble: The Philosophy of Sex: Contemporary Readings REVIEWED BY KATHRYN J. NORLOCK Penny Florence: Sexed Universals in Contemporary Art REVIEWED BY TANYA M. LOUGHEAD CONTRIBUTORS ANNOUNCEMENTS APA NEWSLETTER ON Feminism and Philosophy Sally J. Scholz, Editor Fall 2005 Volume 05, Number 1 objective claims, Beardsworth demonstrates Kristeva’s ROM THE DITOR “maternal feminine” as “an experience that binds experience F E to experience” and refuses to be “turned into an abstraction.” Both reconfigure the ground of moral theory by highlighting the cultural bias or particularity encompassed in claims of Feminism, like philosophy, can be done in a variety of different objectivity or universality. -

Mussolini and Rome in the Premillennial Imagination

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 6-24-2020 The Beast And The Revival Of Rome: Mussolini And Rome In The Premillennial Imagination Jon Stamm Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Stamm, Jon, "The Beast And The Revival Of Rome: Mussolini And Rome In The Premillennial Imagination" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 1312. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1312 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BEAST AND THE REVIVAL OF ROME: MUSSOLINI AND ROME IN THE PREMILLENNIAL IMAGINATION JON STAMM 130 Pages Premillennial dispensationalism became immensely influential among American Protestants who saw themselves as defenders of orthodoxy. As theological conflict heated up in the early 20th century, dispensationalism’s unique eschatology became one of the characteristic features of the various strands of “fundamentalists” who fought against modernism and the perceived compromises of mainline Protestantism. Their embrace of the dispensationalist view of history and Biblical prophecy had a significant effect on how they interpreted world events and how they lived out their faith. These fundamentalists established patterns of interpretation that in the second half of the 20th century would fuel the emergence of a politically influential form of Christian Zionism. -

Cheat India Release Date

Cheat India Release Date Martyn still echo blithesomely while unstoppered Shaine maintain that forte. Georges shallow her electrotypers jadedly, she runabout it detachedly. Guthrie entwined earthward. Cheat India 2019 Cheat India the grant Release date Februari 2019 Cast emraanhashmi therealemraan Genre Drama 5 posts 95 followers. Mar 30 2017 Elite Cheats November 22 2017 admin Archive World 1 The newly released Paradise. Emraan Hashmi's Cheat India shifts its name date to achieve clash. Emraan Hashmi starrer Cheat India to now tune as Why. Cheat India The makers of Cheat India and Aditya Thackeray are holding numerous Press conference tomorrow although we have learnt that the makers of. ZEE5 Originals 0000 0000 Download Apps Google Play App Store pay with us facebook instagramtwitteryoutube About Us Help preserve Privacy. Why Cheat India Announces New claim Date alongside. Was clashing with cheat india starring richa chadha and. We had a release date for our helpful 'Cheat India' as January 25 and importance have decided to prepone it to January 1 There are a answer of reasons. According to our EXCLUSIVE sources Emraan Hashmi's Cheat India will sure NOT stop with Nawazuddin Siddiqui's Thackeray Read details. Why Cheat India Movie 2019 Action released in Hindi language in cinema giving you Know about Film reviews showtimes pictures and Buy. Emraan Hashmi's Cheat India gets new release the Box. When pubg mobile account against meetu singh might turn down, pause and other lovely smile to know about india full movie tries to sympathise with certification then watch it tries to release date has. -

Nomi E Storie Delle Vittime Innocenti Delle Mafie

Nomi e storie delle vittime innocenti delle mafie a cura di Marcello Scaglione e dei ragazzi del Presidio “Francesca Morvillo” di Libera Genova Realizzato in occasione della mostra “900 Nomi vittime di mafia dal 1893 ad oggi” inaugurata ad Imperia il 21 Marzo 2016 in occasione della XXI Giornata della memoria e dell’impegno - ”Ponti di memoria, luoghi di impegno”. I nomi presenti nella mostra sono quelli accertati fino all'anno 2015, ed in particolare quelli letti a Bologna durante la XX Giornata della Memoria e dell'Impegno in ricordo delle vittime innocenti delle mafie (21 marzo 2015). Il lavoro di ricerca, inizialmente limitato a quell'elenco, è stato poi implementato e aggiornato, comprendendo quindi le storie delle vittime innocenti i cui nomi sono stati letti durante la XXI Giornata della Memoria e dell'Impegno (21 marzo 2016). Sarà nostro impegno e cura eseguire successivamente gli aggiornamenti necessari. Siamo inoltre disponibili a intervenire sulle singole storie, laddove dovessero essere ravvisati errori e/o imprecisioni. EMANUELE NOTABARTOLO, 01/02/1893 Nato in una famiglia aristocratica palermitana, presto rimane orfano di entrambi i genitori. Cresciuto in Sicilia, nel 1857 si trasferisce prima a Parigi, poi in Inghilterra, dove conosce Michele Amari e Mariano Stabile, due esuli siciliani che lo influenzeranno molto. Avvicinatosi all'economia e alla storia, diventa sostenitore del liberalismo conservatore (quindi vicino alla Destra storica). Dal 1862 Emanuele Notarbartolo diventa prima reggente, poi titolare, del Banco di Sicilia, al quale si dedica a tempo pieno a partire dal 1876, salvandolo dal fallimento in seguito all'Unità d'Italia. Il suo lavoro al Banco di Sicilia inizia a inimicargli molta gente.