Antimafia Cooperatives: Land, Law, Labour and Moralities in a Changing Sicily

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uccisi I Cugini Del Pentito Calderone

VENERDÌ 11 SETTEMBRE 1992 IN ITALIA PAGINA 13 L'UNITÀ A Bari I killer della mafia hanno ammazzato Una delle vittime era parente dei Costanzo si ristruttura i fratelli Marchese, intoccabili della cosca L'altra era il vecchio capofamiglia il teatro dei clan dominanti della costa orientale Margherita legata al superlatitante di Cosa Nostra iS3b£&rrx«mèm: Da ieri il teatro Margherita di Bari (nella foto) è avvolto Gli investigatori: è l'inizio di una guerra Altri agguati in serata: un morto da teloni che ne riproducono la facciata e ravvivano nella memoria collettiva uno degli edifici più caratteri stici della città, eretto su palafitte di cemento armato al- : l'inizio del lungomare a fare da sfondo a corso Vittorio Emanuele, la cerniera fra il centro storico e i nuovi quar tieri dell'espansione ottocentesca. L'edificio, abbando nato da più di dieci anni e pesantemente degradato, è stato affidato in concessione dallo Stato al gruppo Dio- Uccisi i cugini del pentito Calderone guardi che nei prossimi 12 mesi provvedere a proprie spese (circa 400 milioni) ad evitare l'ulteriore degrado dell'immobile e alla redazione di un progetto per il re cupero e riutilizzo del teatro al quale collaboreranno ar chitetti, urbanisti, sociologi ed esperti di restauro guidati Faida a Catania, massacrati due uomini del boss Santapaola da Renzo Piano. Assassinato a Catania Salvatore Marchese, perso cusati di traffico di droga, Pa i Calderone da Rosario Grasso, «Gli acquarelli «Gli acquarelli di Adolf Hit naggio di spicco del clan Santapaola e cugino del squale Costanzo, zio della mo «sani u'bau». -

Mafia Linguaggio Identità.Pdf

EDIZIONI MAFIA LINGUAGGIO IDENTITÁ di Salvatore Di Piazza Di Piazza, Salvatore <1977-> Mafia, linguaggio, identità / Salvatore Di Piazza – Palermo : Centro di studi ed iniziative culturali Pio La Torre, 2010. (Collana studio e ricerca) 1. Mafia - Linguaggio. 364.10609458 CDD-21 SBN Pal0224463 CIP – Biblioteca centrale della Regione siciliana “Alberto Bombace” 5 Nota editoriale di Vito Lo Monaco, Presidente Centro Pio La Torre 7 Prefazione di Alessandra Dino, sociologa 13 Introduzione Parte Prima 15 Il linguaggio dei mafiosi 15 Un linguaggio o tanti linguaggi? Problemi metodologici 17 Critica al linguaggio-strumento 18 Critica al modello del codice 19 Critica alla specificità tipologica del linguaggio dei mafiosi 19 Mafia e linguaggio 20 La riforma linguistica 21 Le regole linguistiche: omertà o verità 22 La nascita linguistica: performatività del giuramento 23 Caratteristiche del linguaggio dei mafiosi 23 Un gergo mafioso? 26 Un denominatore comune: l’“obliquità semantica” 30 Impliciti, non detti, espressioni metaforiche 36 Un problema concreto: l’esplicitazione dell’implicito Parte Seconda 41 Linguaggio e identità mafiosa 41 Sulla nozione di identità 42 Linguaggio e identità mafiosa tra forma e contenuto 43 Prove tecniche di appartenenza: così parla un mafioso 44 La comunicazione interna 45 La comunicazione esterna 49 La rappresentazione linguistica: un movimento duplice 49 Dall’interno verso l’esterno 51 Dall’esterno verso l’interno 52 Un caso emblematico: i soprannomi 54 Conclusioni 57 Bibliografia di Vito Lo Monaco Il presente lavoro di Salvatore Di Piazza fa parte delle ricerche promosse dal Centro Studi La Torre grazie alla collaborazione volontaria di autorevoli comitati scientifici e al contributo finanziario della Regione Sicilia. -

Mafia E Mancato Sviluppo, Studi Psicologico- Clinici”

C.S.R. C.O.I.R.A.G. Centro Studi e Ricerche “Ermete Ronchi” LA MAFIA, LA MENTE, LA RELAZIONE Atti del Convegno “Mafia e mancato sviluppo, studi psicologico- clinici” Palermo, 20-23 maggio 2010 a cura di Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso QUADERNO REPORT N. 15 Copyright CSR 2011 1 INDICE Nota Editoriale, di Bianca Gallo Presentazione, di Claudio Merlo Introduzione, di Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso Cap. 1 - Ricerche psicologico-cliniche sul fenomeno mafioso • Presentazione, di Santo Di Nuovo Contributi di • Cecilia Giordano • Serena Giunta • Marie Di Blasi, Paola Cavani e Laura Pavia • Francesca Giannone, Anna Maria Ferraro e Francesca Pruiti Ciarello ◦ APPENDICE • Box Approfondimento ◦ Giovanni Pampillonia ◦ Ivan Formica Cap. 2 - Beni relazionali e sviluppo • Presentazione, di Aurelia Galletti Contributi di • Luisa Brunori e Chiara Bleve • Antonino Giorgi • Antonio Caleca • Antonio La Spina • Box Approfondimento ◦ Raffaele Barone, Sheila Sherba e Simone Bruschetta ◦ Salvatore Cernigliano 2 Cap. 3 - Un confronto tra le cinque mafie • Presentazione, di Gianluca Lo Coco Contributi di • Emanuela Coppola • Emanuela Coppola, Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso • Rosa Pinto e Ignazio Grattagliano • Box Approfondimento ◦ Paolo Praticò Cap. 4 - Psicoterapia e mafia • Presentazione, di Giuseppina Ustica Contributi di • Graziella Zizzo • Girolamo Lo Verso • Lorenzo Messina • Maurizio Gasseau Cap. 5 - Oltre il pensiero mafioso • Presentazione, di Antonio Caleca Contributi di • Leoluca Orlando • Maurizio De Lucia • Alfredo Galasso Conclusioni, di Girolamo Lo Verso e Serena Giunta Bibliografia Note 3 Nota editoriale di Bianca Gallo Questo Quaderno CSR, il n° 15, riporta le riflessioni sviluppate attraverso i diversi interventi durante il Convegno Mafia e mancato sviluppo, studi psicologico- clinici, che si è tenuto a Palermo il 20-23 maggio 2010. -

Ercolano, Naples

University of Bath PHD Civil society and the anti-pizzo movement: the case of Ercolano, Naples Bowkett, Chris Award date: 2017 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Civil society and the anti-pizzo movement: the case of Ercolano, Naples Christopher Bowkett A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies September 2017 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis/portfolio rests with the author and copyright of any previously published materials included may rest with third parties. A copy of this thesis/portfolio has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it understands that they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author or other copyright owners, as applicable. -

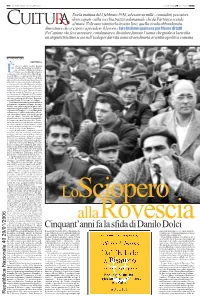

Cinquant'anni Fa La Sfida Di Danilo Dolci

40 LA DOMENICA DI REPUBBLICA DOMENICA 29 GENNAIO 2006 Era la mattina del 2 febbraio 1956, ed erano in mille - contadini, pescatori, disoccupati - sulla vecchia trazzera demaniale che da Partinico scende al mare. Volevano rimetterla in sesto loro, quella strada abbandonata, dimostrare che ci si poteva prendere il lavoro e fare insieme qualcosa per il bene di tutti. Fu l’azione che fece arrestare, condannare e diventare famoso l’uomo che guidava la rivolta: un utopista triestino sceso nell’isola per dar vita a una straordinaria avventura politica e umana ATTILIO BOLZONI PARTINICO ancora senza nome questa strada che dal paese scende fi- no al mare. Ripida nel primo Ètratto, poi va giù dolcemente con le sue curve che sfiorano alberi di pe- sco e di albicocco, passa sotto due ponti, scavalca la ferrovia. L’hanno asfaltata appena una decina di anni fa, prima era un sentiero, una delle tante regie trazze- re borboniche che attraversano la cam- pagna siciliana. È lunga otto chilometri, un giorno forse la chiameranno via dello Sciopero alla Rovescia. Siamo sul ciglio di questa strada di Partinico mezzo se- colo dopo quel 2 febbraio del ‘56, la stia- mo percorrendo sulle tracce di un uomo che sapeva inventare il futuro. Era un ir- regolare Danilo Dolci, uno di confine. Quella mattina erano quasi in mille qui sul sentiero e in mezzo al fango, inverno freddo, era caduta anche la neve sullo spuntone tagliente dello Jato. I pescatori venivano da Trappeto e i contadini dalle valli intorno, c’erano sindacalisti, alleva- tori, tanti disoccupati. E in fondo quegli altri, gli «sbirri» mandati da Palermo, pronti a caricare e a portarseli via quelli lì. -

The Territorial Expansion of Mafia-Type Organized Crime

AperTO - Archivio Istituzionale Open Access dell'Università di Torino The territorial expansion of mafia-type organized crime. The case of the Italian mafia in Germany This is the author's manuscript Original Citation: Availability: This version is available http://hdl.handle.net/2318/141667 since 2016-07-29T11:49:52Z Published version: DOI:10.1007/s10611-013-9473-7 Terms of use: Open Access Anyone can freely access the full text of works made available as "Open Access". Works made available under a Creative Commons license can be used according to the terms and conditions of said license. Use of all other works requires consent of the right holder (author or publisher) if not exempted from copyright protection by the applicable law. (Article begins on next page) 05 October 2021 This is the author's final version of the contribution published as: Rocco Sciarrone and Luca Storti, The territorial expansion of mafia-type organized crime. The case of the Italian mafia in Germany; Crime, Law and Social Change; 2014, vol. 61, issue 1, pp. 37-60, doi:10.1007/s10611-013-9473-7 The publisher's version is available at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10611-013-9473-7 When citing, please refer to the published version. Link to this full text: http://hdl.handle.net/2318/141667 This full text was downloaded from iris-Aperto: https://iris.unito.it/ 1 The territorial expansion of mafia-type organized crime. The case of the Italian mafia in Germany Rocco Sciarrone and Luca Storti Abstract The present paper deals with the territorial movements of the mafia groups. -

LA FAMIGLIA the Ideology of Sicilian Family Networks

LA FAMIGLIA The Ideology of Sicilian Family Networks Eva Carlestål LA FAMIGLIA The Ideology of Sicilian Family Networks Dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Anthropology presented at Uppsala University in 2005 ABSTRACT Carlestål, Eva, 2005. La Famiglia – The Ideology of Sicilian Family Networks. DICA, Disser- tations in Cultural Anthropology, 3. 227 pp. Uppsala. ISSN 1651-7601, ISBN 91-506-1791-5. Anthropological data from fieldwork carried out among a fishing population in western Sicily show how related matrifocal nuclear families are tightly knit within larger, male-headed networks. The mother focus at the basic family level is thereby balanced and the system indi- cates that the mother-child unit does not function effectively on its own, as has often been argued for this type of family structure. As a result of dominating moral values which strong- ly emphasise the uniqueness of family and kin, people are brought up to depend heavily upon and to be loyal to their kin networks, to see themselves primarily as parts of these social units and less so as independent clearly bounded individuals, and to distinctly separate family members from non-family members. This dependence is further strengthened by matri- and/or patrivicinity being the dominant form of locality, by the traditional naming system as well as a continual use of kin terms, and by related people socialising and collaborating closely. The social and physical boundaries thus created around the family networks are further streng- thened by local architecture that symbolically communicates the closed family unit; by the woman, who embodies her family as well as their house, having her outdoor movements restric- ted in order to shield both herself and her family; by self-mastery when it comes to skilfully calculating one's actions and words as a means of controlling the impression one makes on others; and by local patriotism that separates one's co-villagers from foreigners. -

Giuseppe Montalto

Giuseppe Montalto Giuseppe Montalto nacque a Trapani il 14 maggio 1965 e morì a soli 30 anni il 23 dicembre 1995, ucciso da Cosa Nostra. Prestò servizio per vari anni nel carcere “Le Vallette” di Torino, prima di essere trasferito, nel 1993, a Palermo, nella tana dei boss, nella sezione di massima sorveglianza dell’Ucciardone, quella destinata ai criminali che dovevano scontare il regime carcerario del 41 bis. Era il giorno precedente la vigilia di Natale del 1995 quando in contrada Palma, una frazione di Trapani, Giuseppe Montalto fu assassinato da due killer davanti alla moglie: erano in auto e sul sedile posteriore c’era la loro figlioletta, Federica di 10 mesi. La moglie Liliana ancora non sapeva di aspettare la loro secondogenita, Ilenia, che purtroppo non conobbe mai il padre. Era un uomo generoso e buono che mostrava sempre comprensione verso chi viveva tra le sbarre per ripagare il proprio debito con lo Stato, anche quando fu trasferito in Sicilia e cominciò a lavorare a contatto con i boss dell’Ucciardone, nonostante questi continuassero ad ostentare avversione nei confronti dello Stato e delle Istituzioni anche in quel contesto seguitando a recitare la parte dei capi, protetti dallo loro stessa fama di uomini feroci e spregiudicati, nonché scrivendo e spedendo i loro ordini attraverso i pizzini. Anni dopo un pentito, Francesco Milazzo, rivelò che l’agente fu ucciso proprio perché aveva sequestrato un bigliettino fatto arrivare in carcere ai boss Mariano Agate, Raffaele Ganci e Giuseppe Graviano e Cosa nostra non gli perdonò questa applicazione delle norme nel rispetto dello Stato. -

Urban Society and Communal Independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy

Urban society and communal independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy Paul Oldfield Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. The University of Leeds The School of History September 2006 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks for the help of so many different people, without which there would simply have been no thesis. The funding of the AHRC (formerly AHRB) and the support of the School of History at the University of Leeds made this research possible in the first place. I am grateful too for the general support, and advice on reading and sources, provided by Dr. A. J. Metcalfe, Dr. P. Skinner, Professor E. Van Houts, and Donald Matthew. Thanks also to Professor J-M. Martin, of the Ecole Francoise de Rome, for his continual eagerness to offer guidance and to discuss the subject. A particularly large thanks to Mr. I. S. Moxon, of the School of History at the University of Leeds, for innumerable afternoons spent pouring over troublesome Latin, for reading drafts, and for just chatting! Last but not least, I am hugely indebted to the support, understanding and endless efforts of my supervisor Professor G. A. Loud. His knowledge and energy for the subject has been infectious, and his generosity in offering me numerous personal translations of key narrative and documentary sources (many of which are used within) allowed this research to take shape and will never be forgotten. -

Società E Cultura 65

Società e Cultura Collana promossa dalla Fondazione di studi storici “Filippo Turati” diretta da Maurizio Degl’Innocenti 65 1 Manica.indd 1 19-11-2010 12:16:48 2 Manica.indd 2 19-11-2010 12:16:48 Giustina Manica 3 Manica.indd 3 19-11-2010 12:16:53 Questo volume è stato pubblicato grazie al contributo di fondi di ricerca del Dipartimento di studi sullo stato dell’Università de- gli Studi di Firenze. © Piero Lacaita Editore - Manduria-Bari-Roma - 2010 Sede legale: Manduria - Vico degli Albanesi, 4 - Tel.-Fax 099/9711124 www.lacaita.com - [email protected] 4 Manica.indd 4 19-11-2010 12:16:54 La mafia non è affatto invincibile; è un fatto uma- no e come tutti i fatti umani ha un inizio e avrà anche una fine. Piuttosto, bisogna rendersi conto che è un fe- nomeno terribilmente serio e molto grave; e che si può vincere non pretendendo l’eroismo da inermi cittadini, ma impegnando in questa battaglia tutte le forze mi- gliori delle istituzioni. Giovanni Falcone La lotta alla mafia deve essere innanzitutto un mo- vimento culturale che abitui tutti a sentire la bellezza del fresco profumo della libertà che si oppone al puzzo del compromesso, dell’indifferenza, della contiguità e quindi della complicità… Paolo Borsellino 5 Manica.indd 5 19-11-2010 12:16:54 6 Manica.indd 6 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Alla mia famiglia 7 Manica.indd 7 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Leggenda Archivio centrale dello stato: Acs Archivio di stato di Palermo: Asp Public record office, Foreign office: Pro, Fo Gabinetto prefettura: Gab. -

Nomi E Storie Delle Vittime Innocenti Delle Mafie

Nomi e storie delle vittime innocenti delle mafie a cura di Marcello Scaglione e dei ragazzi del Presidio “Francesca Morvillo” di Libera Genova Realizzato in occasione della mostra “900 Nomi vittime di mafia dal 1893 ad oggi” inaugurata ad Imperia il 21 Marzo 2016 in occasione della XXI Giornata della memoria e dell’impegno - ”Ponti di memoria, luoghi di impegno”. I nomi presenti nella mostra sono quelli accertati fino all'anno 2015, ed in particolare quelli letti a Bologna durante la XX Giornata della Memoria e dell'Impegno in ricordo delle vittime innocenti delle mafie (21 marzo 2015). Il lavoro di ricerca, inizialmente limitato a quell'elenco, è stato poi implementato e aggiornato, comprendendo quindi le storie delle vittime innocenti i cui nomi sono stati letti durante la XXI Giornata della Memoria e dell'Impegno (21 marzo 2016). Sarà nostro impegno e cura eseguire successivamente gli aggiornamenti necessari. Siamo inoltre disponibili a intervenire sulle singole storie, laddove dovessero essere ravvisati errori e/o imprecisioni. EMANUELE NOTABARTOLO, 01/02/1893 Nato in una famiglia aristocratica palermitana, presto rimane orfano di entrambi i genitori. Cresciuto in Sicilia, nel 1857 si trasferisce prima a Parigi, poi in Inghilterra, dove conosce Michele Amari e Mariano Stabile, due esuli siciliani che lo influenzeranno molto. Avvicinatosi all'economia e alla storia, diventa sostenitore del liberalismo conservatore (quindi vicino alla Destra storica). Dal 1862 Emanuele Notarbartolo diventa prima reggente, poi titolare, del Banco di Sicilia, al quale si dedica a tempo pieno a partire dal 1876, salvandolo dal fallimento in seguito all'Unità d'Italia. Il suo lavoro al Banco di Sicilia inizia a inimicargli molta gente. -

Finalmente Trema La Nuova Mafia

IN ITALIA «Ecco perché Quattordici arresti eseguiti Indiziate altre 50 persone è crollato a Palermo, Roma e Napoli L'ex «chimico» di Cosa nostra la stadio Dietro il blitz le rivelazioni ha parlato anche dei politici di Palermo» Il crollo nello stadio di Palermo che il 30 maggio scorso pro del pentito Francesco Mannoia favoriti dai boss delle cosche vocò la morte di quattro operai e il ferimento di un quinto deceduto alcuni giorni dopo sarebbe stato causato da alcu ne carenze nelle strutture tecniche e in quelle di s curezza A questa conclusione sono pervenuta tre tecnici - Santi Rizzo Andrea Failla e Fedenco Mazzoiani - incancati dalla magi stratura di eseguire una perizia. La penzia consegnata ieri al sostituto procuratore Giuseppe Pignatone che ha sostituito il titolare dell inchiesta Giuseppe Ayala recentemente trasfe nto dal Csm La causa principale della sciagura viene ricon Finalmente trema la nuova mafia dotta dai penti alla «mancanza della coppia di aste diagona li di controvento» cosi come era stato ipotizzato nella fase iniziale deli inchiesta L indagine tecnica ha inoltre rìscon trato «carenze di progettazione esecutiva» 1 assenza di venfi ca delle condizioni di sicurezza del cantiere interessato al Marino Mannoia crollo e la mancanza di autonzzazione da parte del Genio L In manette i «corleonesi» di Totò Riina civile alla realizzazione di alcune strutture Spiava Un italo-americano attivo in Parla un nuovo grande pentito di mafia Francesco considerato il maestro di avrebbero consentito di met di chimico di cose ne venne socialisti