Nonviolent Resistance Against the Mafia: Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mafia Linguaggio Identità.Pdf

EDIZIONI MAFIA LINGUAGGIO IDENTITÁ di Salvatore Di Piazza Di Piazza, Salvatore <1977-> Mafia, linguaggio, identità / Salvatore Di Piazza – Palermo : Centro di studi ed iniziative culturali Pio La Torre, 2010. (Collana studio e ricerca) 1. Mafia - Linguaggio. 364.10609458 CDD-21 SBN Pal0224463 CIP – Biblioteca centrale della Regione siciliana “Alberto Bombace” 5 Nota editoriale di Vito Lo Monaco, Presidente Centro Pio La Torre 7 Prefazione di Alessandra Dino, sociologa 13 Introduzione Parte Prima 15 Il linguaggio dei mafiosi 15 Un linguaggio o tanti linguaggi? Problemi metodologici 17 Critica al linguaggio-strumento 18 Critica al modello del codice 19 Critica alla specificità tipologica del linguaggio dei mafiosi 19 Mafia e linguaggio 20 La riforma linguistica 21 Le regole linguistiche: omertà o verità 22 La nascita linguistica: performatività del giuramento 23 Caratteristiche del linguaggio dei mafiosi 23 Un gergo mafioso? 26 Un denominatore comune: l’“obliquità semantica” 30 Impliciti, non detti, espressioni metaforiche 36 Un problema concreto: l’esplicitazione dell’implicito Parte Seconda 41 Linguaggio e identità mafiosa 41 Sulla nozione di identità 42 Linguaggio e identità mafiosa tra forma e contenuto 43 Prove tecniche di appartenenza: così parla un mafioso 44 La comunicazione interna 45 La comunicazione esterna 49 La rappresentazione linguistica: un movimento duplice 49 Dall’interno verso l’esterno 51 Dall’esterno verso l’interno 52 Un caso emblematico: i soprannomi 54 Conclusioni 57 Bibliografia di Vito Lo Monaco Il presente lavoro di Salvatore Di Piazza fa parte delle ricerche promosse dal Centro Studi La Torre grazie alla collaborazione volontaria di autorevoli comitati scientifici e al contributo finanziario della Regione Sicilia. -

Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri's Detective

MAFIA MOTIFS IN ANDREA CAMILLERI’S DETECTIVE MONTALBANO NOVELS: FROM THE CULTURE AND BREAKDOWN OF OMERTÀ TO MAFIA AS A SCAPEGOAT FOR THE FAILURE OF STATE Adriana Nicole Cerami A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Dino S. Cervigni Amy Chambless Roberto Dainotto Federico Luisetti Ennio I. Rao © 2015 Adriana Nicole Cerami ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Adriana Nicole Cerami: Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri’s Detective Montalbano Novels: From the Culture and Breakdown of Omertà to Mafia as a Scapegoat for the Failure of State (Under the direction of Ennio I. Rao) Twenty out of twenty-six of Andrea Camilleri’s detective Montalbano novels feature three motifs related to the mafia. First, although the mafia is not necessarily the main subject of the narratives, mafioso behavior and communication are present in all novels through both mafia and non-mafia-affiliated characters and dialogue. Second, within the narratives there is a distinction between the old and the new generations of the mafia, and a preference for the old mafia ways. Last, the mafia is illustrated as the usual suspect in everyday crime, consequentially diverting attention and accountability away from government authorities. Few critics have focused on Camilleri’s representations of the mafia and their literary significance in mafia and detective fiction. The purpose of the present study is to cast light on these three motifs through a close reading and analysis of the detective Montalbano novels, lending a new twist to the genre of detective fiction. -

Mafia E Mancato Sviluppo, Studi Psicologico- Clinici”

C.S.R. C.O.I.R.A.G. Centro Studi e Ricerche “Ermete Ronchi” LA MAFIA, LA MENTE, LA RELAZIONE Atti del Convegno “Mafia e mancato sviluppo, studi psicologico- clinici” Palermo, 20-23 maggio 2010 a cura di Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso QUADERNO REPORT N. 15 Copyright CSR 2011 1 INDICE Nota Editoriale, di Bianca Gallo Presentazione, di Claudio Merlo Introduzione, di Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso Cap. 1 - Ricerche psicologico-cliniche sul fenomeno mafioso • Presentazione, di Santo Di Nuovo Contributi di • Cecilia Giordano • Serena Giunta • Marie Di Blasi, Paola Cavani e Laura Pavia • Francesca Giannone, Anna Maria Ferraro e Francesca Pruiti Ciarello ◦ APPENDICE • Box Approfondimento ◦ Giovanni Pampillonia ◦ Ivan Formica Cap. 2 - Beni relazionali e sviluppo • Presentazione, di Aurelia Galletti Contributi di • Luisa Brunori e Chiara Bleve • Antonino Giorgi • Antonio Caleca • Antonio La Spina • Box Approfondimento ◦ Raffaele Barone, Sheila Sherba e Simone Bruschetta ◦ Salvatore Cernigliano 2 Cap. 3 - Un confronto tra le cinque mafie • Presentazione, di Gianluca Lo Coco Contributi di • Emanuela Coppola • Emanuela Coppola, Serena Giunta e Girolamo Lo Verso • Rosa Pinto e Ignazio Grattagliano • Box Approfondimento ◦ Paolo Praticò Cap. 4 - Psicoterapia e mafia • Presentazione, di Giuseppina Ustica Contributi di • Graziella Zizzo • Girolamo Lo Verso • Lorenzo Messina • Maurizio Gasseau Cap. 5 - Oltre il pensiero mafioso • Presentazione, di Antonio Caleca Contributi di • Leoluca Orlando • Maurizio De Lucia • Alfredo Galasso Conclusioni, di Girolamo Lo Verso e Serena Giunta Bibliografia Note 3 Nota editoriale di Bianca Gallo Questo Quaderno CSR, il n° 15, riporta le riflessioni sviluppate attraverso i diversi interventi durante il Convegno Mafia e mancato sviluppo, studi psicologico- clinici, che si è tenuto a Palermo il 20-23 maggio 2010. -

Ercolano, Naples

University of Bath PHD Civil society and the anti-pizzo movement: the case of Ercolano, Naples Bowkett, Chris Award date: 2017 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Civil society and the anti-pizzo movement: the case of Ercolano, Naples Christopher Bowkett A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies September 2017 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis/portfolio rests with the author and copyright of any previously published materials included may rest with third parties. A copy of this thesis/portfolio has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it understands that they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author or other copyright owners, as applicable. -

International Sales Autumn 2017 Tv Shows

INTERNATIONAL SALES AUTUMN 2017 TV SHOWS DOCS FEATURE FILMS THINK GLOBAL, LIVE ITALIAN KIDS&TEEN David Bogi Head of International Distribution Alessandra Sottile Margherita Zocaro Cristina Cavaliere Lucetta Lanfranchi Federica Pazzano FORMATS Marketing and Business Development [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mob. +39 3351332189 Mob. +39 3357557907 Mob. +39 3334481036 Mob. +39 3386910519 Mob. +39 3356049456 INDEX INDEX ... And It’s Snowing Outside! 108 As My Father 178 Of Marina Abramovic 157 100 Metres From Paradise 114 As White As Milk, As Red As Blood 94 Border 86 Adriano Olivetti And The Letter 22 46 Assault (The) 66 Borsellino, The 57 Days 68 A Case of Conscience 25 At War for Love 75 Boss In The Kitchen (A) 112 A Good Season 23 Away From Me 111 Boundary (The) 50 Alex&Co 195 Back Home 12 Boyfriend For My Wife (A) 107 Alive Or Preferably Dead 129 Balancing Act (The) 95 Bright Flight 101 All The Girls Want Him 86 Balia 126 Broken Years: The Chief Inspector (The) 47 All The Music Of The Heart 31 Bandit’s Master (The) 53 Broken Years: The Engineer (The) 48 Allonsanfan 134 Bar Sport 118 Broken Years: The Magistrate (The) 48 American Girl 42 Bastards Of Pizzofalcone (The) 15 Bruno And Gina 168 Andrea Camilleri: The Wild Maestro 157 Bawdy Houses 175 Bulletproof Heart (A) 1, 2 18 Angel of Sarajevo (The) 44 Beachcombers 30 Bullying Lesson 176 Anija 173 Beauty And The Beast (The) 54 Call For A Clue 187 Anna 82 Big Racket (The) -

STRUTTURE Cosa Nostra E 'Ndrangheta a Confronto

STRUTTURE Cosa Nostra e ‘ndrangheta a confronto Francesco Gaetano Moiraghi Andrea Zolea WikiMafia – Libera Enciclopedia sulle Mafie www.wikimafia.it Strutture: Cosa Nostra e ‘ndrangheta a confronto, di Francesco Gaetano Moiraghi e Andrea Zolea La mafia dura da decenni: un motivo ci deve essere. Non si può andare contro i missili con arco e frecce: in queste vicende certe intemperanze si pagano duramente. Con il terrorismo, con il consenso sociale, potevi permettertele: con la mafia non è così. Nella società c’è un consenso distorto. Altro che bubbone in un tessuto sociale sano. Il tessuto non è affatto sano. Noi estirperemo Michele Greco, poi arriverà il secondo, poi il terzo, poi il quarto. Giovanni Falcone 1 www.wikimafia.it Strutture: Cosa Nostra e ‘ndrangheta a confronto, di Francesco Gaetano Moiraghi e Andrea Zolea PREMESSA Questo lavoro ha lo scopo di offrire uno sguardo d’insieme sulle articolazioni strutturali delle organizzazioni mafiose denominate Cosa nostra e ‘ndrangheta . La prima sezione, curata da Francesco Gaetano Moiraghi, si concentra sull’analisi di Cosa nostra. La seconda sezione, che sposta il focus sulla ‘ndrangheta, è curata da Andrea Zolea. Come si potrà notare, le due sezioni non sono state realizzate secondo uno stesso modello, ma analizzano le due organizzazioni con un approccio differente. Ad esempio, la parte su Cosa nostra avrà un orientamento maggiormente diacronico, diversamente da quella sulla ‘ndrangheta, basata su un approccio sincronico. Il presente testo ha infatti l’obiettivo di offrire due proposte di analisi differenti che riescano a mettere in luce le analogie e le differenze delle strutture delle due organizzazioni mafiose. -

La Mafia Imprenditrice

INFILTRAZIONI MAFIOSE mafiosa e non, ci rendiamo conto, in- L’ultimo rapporto di Sos Impresa fatti, che questa incide direttamente sul mondo dell’impresa, superando i 92 miliardi di euro di fatturato, una cifra intorno al 6% del Pil nazionale. Sostan- La mafia zialmente, ogni giorno, una massa enorme di denaro passa dalle tasche dei commercianti e degli imprenditori italiani a quelle dei mafiosi, qualcosa imprenditrice come 250 milioni di euro, 10 milioni l’ora, 160 mila euro al minuto. Ci troviamo di fronte a una mafia im- Come vere e proprie holding, le mafie sono dentro al “merca- prenditrice, ormai presente in ogni to”, ne seguono gli sviluppi, pianificano investimenti. Si con- comparto economico e finanziario del sistema Paese, non solo per quanto ri- frontano con la concorrenza ora conquistando posizione di guarda l’attività predatoria, rappresen- tata dal racket delle estorsioni e monopolio in forza della capacità di intimidazione, ora stabi- dall’usura, ma anche per quella del lendo rapporti collusivi con “pezzi” di imprenditoria fautori di reinvestimento di denaro sporco. L’attività imprenditoriale delle mafie ha quella doppia morale per cui “gli affari, sono affari” prodotto un’organizzazione interna ti- picamente aziendale con tanto di ma- di Bianca La Rocca strutturati e agguerriti. E questi, ben- nager, dirigenti, addetti e consulenti. ché duramente colpiti dall’azione delle La gestione delle estorsioni, dell’usura, on un fatturato di 130 miliardi di forze dell’ordine e della magistratura, dell’imposizione di merce, dello spac- Ceuro e un utile che sfiora i 70 continuano a mantenere pressoché cio di stupefacenti, necessita, di fatto, miliardi la Mafia Spa si conferma la inalterata la loro forza e, per ora, la lo- di un organico in pianta stabile, che più grande holding company italia- ro strategia, che si dimostra vincente. -

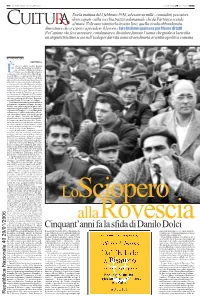

Cinquant'anni Fa La Sfida Di Danilo Dolci

40 LA DOMENICA DI REPUBBLICA DOMENICA 29 GENNAIO 2006 Era la mattina del 2 febbraio 1956, ed erano in mille - contadini, pescatori, disoccupati - sulla vecchia trazzera demaniale che da Partinico scende al mare. Volevano rimetterla in sesto loro, quella strada abbandonata, dimostrare che ci si poteva prendere il lavoro e fare insieme qualcosa per il bene di tutti. Fu l’azione che fece arrestare, condannare e diventare famoso l’uomo che guidava la rivolta: un utopista triestino sceso nell’isola per dar vita a una straordinaria avventura politica e umana ATTILIO BOLZONI PARTINICO ancora senza nome questa strada che dal paese scende fi- no al mare. Ripida nel primo Ètratto, poi va giù dolcemente con le sue curve che sfiorano alberi di pe- sco e di albicocco, passa sotto due ponti, scavalca la ferrovia. L’hanno asfaltata appena una decina di anni fa, prima era un sentiero, una delle tante regie trazze- re borboniche che attraversano la cam- pagna siciliana. È lunga otto chilometri, un giorno forse la chiameranno via dello Sciopero alla Rovescia. Siamo sul ciglio di questa strada di Partinico mezzo se- colo dopo quel 2 febbraio del ‘56, la stia- mo percorrendo sulle tracce di un uomo che sapeva inventare il futuro. Era un ir- regolare Danilo Dolci, uno di confine. Quella mattina erano quasi in mille qui sul sentiero e in mezzo al fango, inverno freddo, era caduta anche la neve sullo spuntone tagliente dello Jato. I pescatori venivano da Trappeto e i contadini dalle valli intorno, c’erano sindacalisti, alleva- tori, tanti disoccupati. E in fondo quegli altri, gli «sbirri» mandati da Palermo, pronti a caricare e a portarseli via quelli lì. -

Irno Scarani, Cronache Di Luce E Sangue (Edizione Del Giano, 2013), 128 Pp

Book Reviews Irno Scarani, Cronache di luce e sangue (Edizione del Giano, 2013), 128 pp. Nina Bjekovic University of California, Los Angeles The contemporary art movement known as Neo-Expressionism emerged in Europe and the United States during the late 1970s and early 1980s as a reaction to the traditional abstract and minimalist art standards that had previously dominated the market. Neo-Expressionist artists resurrected the tradition of depicting content and adopted a preference for more forthright and aggressive stylistic techniques, which favored spontaneous feeling over formal structures and concepts. The move- ment’s predominant themes, which include human angst, social alienation, and political tension reemerge in a similar bold tone in artist and poet Irno Scarani’s Cronache di luce e sangue. This unapologetic, vigorous, and sensible poetic contem- plation revisits some of the most tragic events that afflicted humanity during the twentieth century. Originating from a personal urgency to evaluate the experience of human existence and the historical calamities that bear everlasting consequences, the poems, better yet chronicles, which comprise this volume daringly examine the fear and discomfort that surround these disquieting skeletons of the past. Cronache di luce e sangue reflects the author’s firsthand experience in and expo- sure to the civil war in Italy—the highly controversial period between September 8, 1943, the date of the armistice of Cassibile, and May 2, 1945, the surrender of Nazi Germany, when the Italian Resistance and the Co-Belligerent Army joined forces in a war against Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Italian Social Republic. Born in Milan in 1937 during the final period of the Fascist regime, Scarani became acquainted with violence and war at a very young age. -

Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino: Due Vite INTRECCIATE

Protagonisti Quella domenica il caldo era oppri- sirene. Per me cominciò così l’incu- mente e la città si era svuotata. bo di via D’Amelio. All’inizio della 16:58, Palermo Il telefono di casa squillò alle 17. strada vidi un pezzo di braccio car- Era una mia amica che terrorizzata bonizzato, mi era sembrato un rotta- come Beirut mi diceva «sono tremati i palazzi, me, solo dopo capii che cos’era. Mi c’è stata una bomba, vieni». Un paio muovevo come un automa in mezzo alle Il primo giornalista arrivato in di minuti ed ero già sul posto. Le auto in fiamme, improvvisamente non via D’Amelio pochi minuti dopo fiamme avvolgevano decine di auto, c’era più caldo. Arrivarono i vigili i palazzi erano sventrati, dalle ma- del fuoco e le prime volanti, tutti la strage ricorda quel terribile cerie vedevi apparire gente sangui- correvano ma nessuno ancora sapeva pomeriggio. Attimo per attimo. nante, suonavano decine di allarmi e quello che era successo. Non si sa- Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino: due vite INTRECCIATE , Il coraggio UNA COPPIA “SCOMODA”A” Falcone e Borsellino sorridenti durante un dibattito a Palermo nel 1992. Alle loro spalle, i luoghi dove sono stati uccisi: rispettivamente, lo svincolo per Capaci e via D’Amelio a Palermo. peva neanche chi era stato ucciso, terra a pochi metri dal portone noi giornalisti cercavamo di capi- il primo nome che venne fuori fu d’ingresso, vicino a lui il corpo di re, ma mai capire era stato così quello del giudice Ayala. Ma Ayala uno dei suoi uomini. -

Società E Cultura 65

Società e Cultura Collana promossa dalla Fondazione di studi storici “Filippo Turati” diretta da Maurizio Degl’Innocenti 65 1 Manica.indd 1 19-11-2010 12:16:48 2 Manica.indd 2 19-11-2010 12:16:48 Giustina Manica 3 Manica.indd 3 19-11-2010 12:16:53 Questo volume è stato pubblicato grazie al contributo di fondi di ricerca del Dipartimento di studi sullo stato dell’Università de- gli Studi di Firenze. © Piero Lacaita Editore - Manduria-Bari-Roma - 2010 Sede legale: Manduria - Vico degli Albanesi, 4 - Tel.-Fax 099/9711124 www.lacaita.com - [email protected] 4 Manica.indd 4 19-11-2010 12:16:54 La mafia non è affatto invincibile; è un fatto uma- no e come tutti i fatti umani ha un inizio e avrà anche una fine. Piuttosto, bisogna rendersi conto che è un fe- nomeno terribilmente serio e molto grave; e che si può vincere non pretendendo l’eroismo da inermi cittadini, ma impegnando in questa battaglia tutte le forze mi- gliori delle istituzioni. Giovanni Falcone La lotta alla mafia deve essere innanzitutto un mo- vimento culturale che abitui tutti a sentire la bellezza del fresco profumo della libertà che si oppone al puzzo del compromesso, dell’indifferenza, della contiguità e quindi della complicità… Paolo Borsellino 5 Manica.indd 5 19-11-2010 12:16:54 6 Manica.indd 6 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Alla mia famiglia 7 Manica.indd 7 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Leggenda Archivio centrale dello stato: Acs Archivio di stato di Palermo: Asp Public record office, Foreign office: Pro, Fo Gabinetto prefettura: Gab. -

LE MENTI RAFFINATISSIME Di Paolo Mondani E Giorgio Mottola

1 LE MENTI RAFFINATISSIME Di Paolo Mondani e Giorgio Mottola Collaborazione Norma Ferrara, Alessia Pelagaggi e Roberto Persia Immagini Dario D’India, Alfredo Farina e Alessandro Spinnato Montaggio e grafica Giorgio Vallati GIUSEPPE LOMBARDO - PROCURATORE AGGIUNTO TRIBUNALE DI REGGIO CALABRIA Licio Gelli era il perno. Perché attraverso la P2 lui controllava i Servizi. GIANMARIO FERRAMONTI - EX POLITICO LEGA NORD Essere lontani da Cosa Nostra se si agisce in Sicilia è molto difficile. CONSOLATO VILLANI - COLLABORATORE DI GIUSTIZIA Dietro le stragi c'erano i servizi segreti deviati GIOACCHINO GENCHI - EX UFFICIALE POLIZIA DI STATO La principale intenzione era quella di non trovare i veri colpevoli. PIETRO RIGGIO - COLLABORATORE DI GIUSTIZIA - 19/10/2020 PROCESSO D'APPELLO TRATTATIVA STATO-MAFIA L'indicatore dei luoghi dove erano avvenute le stragi fosse stato Marcello Dell'Utri. ROBERTO TARTAGLIA – EX PM PROCESSO TRATTATIVA STATO-MAFIA Chi è che insegna a Salvatore Riina il linguaggio che abbina la cieca violenza mafiosa alla raffinata guerra psicologica di disinformazione che c’è dietro l'operazione della Fa- lange Armata? NINO DI MATTEO - MAGISTRATO PROCESSO TRATTATIVA - MEMBRO CSM È successo anche questo, scoprire che un presidente della Repubblica aveva mentito. SILVIO BERLUSCONI - EX PRESIDENTE DEL CONSIGLIO Io su indicazione dei miei avvocati intendo avvalermi della facoltà di non rispondere. SIGFRIDO RANUCCI IN STUDIO Buonasera, parleremo del periodo stragista che va dal 1992 al 1994, della presunta trattativa tra Stato e Mafia. Lo faremo con documenti e testimonianze inedite, tra le quali quella di Salvatore Baiardo, l’uomo che ha gestito la latitanza dei fratelli Graviano, una potente famiglia mafiosa, oggi accusata di essere l’autrice della strage di via d’Ame- lio.