The National Monetary Commission: American Banking’S Debt to Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Option in Housing Finance

The Public Option in Housing Finance Adam J. Levitin†* and Susan M. Wachter** The U.S. housing finance system presents a conundrum for the scholar of regulation because it defies description using the traditional regulatory vocabulary of command-and-control, taxation, subsidies, cap-and-trade permits, and litigation. Instead, since the New Deal, the housing finance market has been regulated primarily by government participation in the market through a panoply of institutions. The government’s participation in the market has shaped the nature of the products offered in the market. We term this form of regulation “public option” regulation. This Article presents a case study of this “public option” as a regulatory mode. It explains the public option’s rise as a governmental gap-filling response to market failures. The public option, however, took on a life of its own as the federal government undertook financial innovations that the private market had eschewed, in particular the development of the “American mortgage” — a long-term, fixed-rate fully amortizing mortgage. These innovations were trend-setting and set the tone for entire housing finance market, serving as functional regulation. The public option was never understood as a regulatory system due to its ad hoc nature. As a result, its integrity was not protected. Key parts of the system were privatized without a substitution of alternative regulatory measures. The consequence was a return to the very market failures that led to the public option in the first place, followed by another round of ad hoc public options in housing finance. This history suggests that an † Copyright © 2013 Adam J. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 83 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1997 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Richard Spillenkothen • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 947 TREASURY AND FEDERAL RESERVE OPEN formance can improve investor and counterparty MARKET OPERATIONS decisions, thus improving market discipline on banking organizations and other companies, During the third quarter of 1997, the dollar before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, appreciated 5.0 percent against the Japanese yen Securities and Government Sponsored Enter- and 0.8 percent against the German mark. On a prises of the House Committee on Banking and trade-weighted basis against other Group of Ten Financial Services, October 1, 1997. currencies, the dollar appreciated 1.4 percent. The U.S. monetary authorities did not undertake 96\ Theodore E. Allison, Assistant to the Board of any intervention in the foreign exchange mar- Governors for Federal Reserve System Affairs, kets during the quarter. reports on the Federal Reserve's plans for deal- ing with some new-design $50 notes that 953 STAFF STUDY SUMMARY were imperfectly printed, including the Federal Reserve's view of the quality and quantity of In The Cost of Implementing Consumer Finan- $50 notes currently being produced by the cial Regulations, the authors present results for Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the options U.S. -

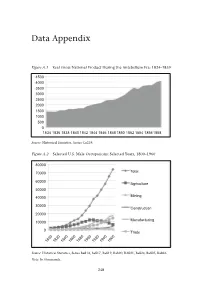

Data Appendix

Data Appendix Figure A.1 Real Gross National Product During the Antebellum Era: 1834–1859 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1834 1836 1838 1840 1842 1844 1846 1848 1850 1852 1854 18561858 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ca219. Figure A.2 Selected U.S. Male Occupations: Selected Years, 1800–1960 80000 70000 Total 60000 Agriculture 50000 40000 Mining 30000 Construction 20000 Manufacturing 10000 0 Trade 1800 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ba814, Ba817, Ba819, Ba820, BA821, Ba824, Ba825, Ba826. Note: In thousands. 248 Source Source Note Source Figure A.5 Figure A.4 Figure A.3 : ThisistheSchwert’sIndexofCommonStock. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesAa36,Aa46, Aa56. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCh411. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCj979. 100000000 150000000 200000000 250000000 300000000 100000 120000 10 12 14 16 50000000 20000 40000 60000 80000 0 2 4 6 8 0 1802 0 U.S. PopulationforSelectedYears:1790–1990 Total NumberofU.S.BusinessFailures:1857–1997 1805 Stock IndexDuringtheAntebellumEra:1802–1870 1857 1790 1830 1860 1890 1920 1950 1990 1808 1863 1869 1811 1875 1814 1881 1817 1887 1820 1893 1823 1899 1826 1905 1829 1911 1832 1917 1835 1923 1838 1929 1841 1935 1941 1844 1947 1847 1953 1850 1959 1853 Total RuralPopulation Total UrbanPopulation Total Population Total 1965 1856 Data Appendix 1971 1859 1977 1862 1983 1865 1989 1995 1868 249 Note Source Note Source Figure A.8 up totheGreatDepression:1869–1929 Figure A.7 250 Source: Figure A.6 : ThisistheIndustrialsIndex. : ThisdataisfromGallman-Kuznetsestimationandin1929dollars. -

History of Banking in the U.S. (9/30/2010) Econ 310-004

History of Banking in the U.S. (9/30/2010) Econ 310‐004 Definitions • independent treasury – separation of bank and state • laissez faire – transactions between private parties are free from state intervention, including restrictive regulations, taxes, tariffs and enforced monopolies • mercantilism – alliance between government and certain privileged merchants • interstate branch banking – the ability of a bank to have branches in more than one state • intrastate branch banking – the ability of a bank to have multiple branches in the same state • unit banking – no interstate or intrastate branching • fractional currency – currency in denominations less than a dollar (e.g., 5¢, 10¢, 25¢, etc.) • bond collateral requirement – dollar for dollar banknote to state bond ratio • wildcat banking – fraudulent banks setup in wilderness that made it very hard to redeem notes • inelastic currency – inability of the system to convert deposits into banknotes Principles • Banking has always been one of the most regulated industries. • Branching allows diversification. o Assets: Without branching banks only loan locally, so when the local economy goes bad, many loans default at once. o Liabilities: Without branching banks only get deposits locally, so when the local economy goes bad, many customers withdraw at once. • The stability of the bank system effects the reserve rate, not the other way around. • Bond collateral requirement led to more bank panics due to inelastic currency. Alexander Hamilton early state banks • Secretary of the Treasury (Washington) • 1776‐1837 • formed United States Mint • regulation at state level • got Morris to form Bank of North America • no general incorporation for banks • started Bank of New York • 9/31 states outlawed banking • architect of 1st bank of the United States • some states setup monopoly banks • killed by Aaron Burr (VP) in a duel • some still chartered banks • 6 states tried deposit/note insurance Andrew Jackson • President of U.S. -

The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E

Maryland Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 3 Article 3 Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E. Willis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Banking and Finance Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Lauren E. Willis, Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price, 65 Md. L. Rev. 707 (2006) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARYLAND LAW REVIEW VOLUME 65 2006 NUMBER 3 © Copyright Maryland Law Review 2006 Articles DECISIONMAKING AND THE LIMITS OF DISCLOSURE: THE PROBLEM OF PREDATORY LENDING: PRICE LAUREN E. WILLIS* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 709 I. PREDATORY LENDING AND THE HOME LOAN MARKET ...... 715 A. The Home Lending Revolution ........................ 715 1. The Twentieth Century Marketplace: Standardized Terms, Limited and Advertised Prices, and Low Risk. 715 2. The Brave New World of ProliferatingProducts, Price, and R isk ........................................ 718 3. Evidence of Predatory Home Lending ............... 729 B. A New Definition of Predatory Lending ................. 735 II. FEDERAL LAW REGULATING THE PRICING OF HOME- SECURED LOANS: DISCLOSURE AS PANACEA ................ 741 A. The Rational Actor Decisionmaker Model ............... 741 B. CurrentFederal Law .................................. 743 C. Even a Rational Actor Could Not Use the Federal Disclosures to Price Shop in Today's Marketplace ....... -

The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 159–181 The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed Robert L. Hetzel ilton Friedman (1982, 103) wrote: “In our book on U.S. mon- etary history, Anna Schwartz and I found it possible to use M one sentence to describe the central principle followed by the Federal Reserve System from the time it began operations in 1914 to 1952. That principle, to quote from our book, is: ‘Ifthe ‘money market’ is properly managed so as to avoid the unproductive use of credit and to assure the availability of credit for productive use, then the money stock will take care of itself.’” For Friedman, the reference to “the money stock”was synonymous with “the price level.”1 How did American monetary experience and debate in the 19th century give rise to these “real bills” views as a guide to Fed policy in the pre-World War II period? As distilled in the real bills doctrine, the founders of the Fed under- stood the Federal Reserve System as a decentralized system of reserve depositories that would allow the expansion and contraction of currency and credit based on discounting member-bank paper that originated out of productive activity. By discounting these “real bills,”the short- term loans that …nanced trade and goods in the process of production, policymakers ful…lled their responsibilities as they understood them. That is, they would provide the reserves required to accommodate the “legitimate,” nonspeculative, demands for credit.2 In so doing, they The author acknowledges helpful comments from Huberto Ennis, Motoo Haruta, Gary Richardson, Robert Sharp, Kurt Schuler, Ellis Tallman, and Alexander Wolman. -

The Evolution of Fed Independence

FEDERALRESERVE The Evolution of Fed Independence BY STEPHEN SLIVINSKI oday there is a consensus Wars, Depression, and How monetary policy that a central bank can best Dependence T contribute to good economic When the United States entered and central bank performance by pursuing price stabil- World War I in April 1917, the Federal ity — and that it should remain inde- Reserve almost instantly became the autonomy came pendent from political forces. In the primary vehicle for financing the war case of price stability, this understand- effort. The main function of the Fed of age ing evolved over decades of experi- during those war years was to lend ence. The notion of independence of money to banks to purchase “Liberty the central bank was more difficult to Loans” bonds from the U.S. Treasury. fulfill. They loaned the money at a discount- The original conception of the ed rate — not coincidentally lower Federal Reserve System when it was than the interest rate on the war bonds created in 1913 was meant to continue — to entice bond purchasers. After the spirit of the “independent treasury the war, the Federal Reserve Bank of system” that existed in the pre-Fed New York remained the official era. That system assumed that the U.S. fiscal agent of the U.S. Treasury Treasury would store its gold and Department. assets in its own vaults lest it unduly In the post-war years, the Fed influence the markets for credit and busied itself with maintaining the money. Ideally, Treasury meddling in newly reconstructed gold standard. what passed for monetary policy at the Its missteps in the wake of the stock time was to be avoided. -

FDIC Banking Review, Vol. 17, No. 4

Banking Review 2005 VOLUME 17, NO. 4 The U.S. Federal Financial Regulatory System: Restructuring Federal Bank Regulation (page 1) by Rose Marie Kushmeider Most observers of the U.S. financial regulatory system would agree that if it did not exist, no one would invent it. Most, however, would also admit that the system–despite all its faults–has served both the financial services industry and consumers well. This paper looks at arguments for and against reform in the context of changes taking place within the industry and around the world in other financial regulatory systems. Consolidation in the U.S. Banking Industry: Is the “Long, Strange Trip” About to End? (page 31) by Kenneth D. Jones and Tim Critchfield Consolidation has been an enduring trend in the U.S. banking industry for more than two decades. This article provides an overview of the structural changes that have occurred and explores the empirical research to determine how consolidtion has affected such things as asset concentration, competition, banking efficiency and profitability, shareholder value, and the availability and pricing of banking services. Finally, the authors speculate on how the current forces of change might affect the industy’s structure going forward. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Articles may be reprinted or abstracted if the FDIC Banking Review and author(s) are credited. Please provide the FDIC’s Division of Insurance and Research with a copy of any publications containing reprinted material. Acting Chairman Martin J. Gruenberg Director, Division of Insurance Arthur J. -

Central Banking in the United States: a Fragile Commitment to Price Stability and Independence

Contents ~ Foreword ~ Central Banking in the United States: A Fragile Commitment to Price Stability and Independence ~ Comparative Financial Statements ~ Directors ~ Officers Forevvord ~ ineteen ninety-one was a year of changes policy adjustments-and there will doubtless be and often the changes took unexpected turns. many - should focus on this goal. The long-awaited bank reform bill was passed, but disappointed many in its lack of vision. The Twenty-three directors, representing banking, economy, which many observers expected to business, agriculture, consumer, and labor inter recover, seemed to stall and then founder at the ests, guide the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland close of the year. and its Branches. Their contributions are highly valued, as is the participation of our Small Bank At the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, and Small Business Advisory Councils. change also occurred with the departure of our president, W Lee Hoskins, and the appointment Special thanks are extended to those directors of our new president, Jerry L. Jordan. who have completed their terms of service on our boards. We are especially grateful for the leader Lee, who left to become president and chief ship of Kate Ireland (national chairman, Frontier executive officer of The Huntington National Nursing Service of Wendover, Kentucky), who Bank, made noteworthy contributions on several was chairman of our Cincinnati Branch board fronts. He developed influential public policy of directors. We also appreciate the contributions positions on the importance of price stability of Allen L. Davis (president and chief executive and financial regulatory reform. Under his officer of The Provident Bank, Cincinnati, Ohio), leadership, the Fourth District made signifi who served on our Cincinnati Branch board; and cant progress toward becoming the lowest-cost E. -

Antebellum Banking Regulation: a Comparative Approach

ANTEBELLUM BANKING REGULATION: A COMPARATIVE APPROACH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alka Gandhi, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Richard H. Steckel, Advisor Professor Paul Evans ________________________ Advisor Professor J. Huston McCulloch Economics Graduate Program ABSTRACT Extensive historical and contemporary studies establish important links between financial systems and economic development. Despite the importance of this research area and the extent of prior efforts, numerous interesting questions remain about the consequences of alternative regulatory regimes for the health of the financial sector. As a dynamic period of economic and financial evolution, which was accompanied by diverse banking regulations across states, the antebellum era provides a valuable laboratory for study. This dissertation utilizes a rich data set of balance sheets from antebellum banks in four U.S. states, Massachusetts, Ohio, Louisiana and Tennessee, to examine the relative impacts of preventative banking regulation on bank performance. Conceptual models of financial regulation are used to identify the motivations behind each state’s regulation and how it changed over time. Next, a duration model is employed to model the odds of bank failure and to determine the impact that regulation had on the ability of a bank to remain in operation. Finally, the estimates from the duration model are used to perform a counterfactual that assesses the impact on the odds of bank failure when imposing one state’s regulation on another state, ceteris paribus. The results indicate that states did enact regulation that was superior to alternate contemporaneous banking regulation, with respect to the ability to maintain the banking system. -

Once Bitten, Twice Shy: Rethinking the Federal Reserve’S Independence and Monetary Policy in the U.S

ONCE BITTEN, TWICE SHY: RETHINKING THE FEDERAL RESERVE’S INDEPENDENCE AND MONETARY POLICY IN THE U.S. by Niveditha Prabakaran B.S. Mathematics-Economics, B.A. Politics and Philosophy School of Arts and Sciences 2011 Submitted to the Undergraduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Niveditha Prabakaran It was defended on April 20, 2011 and approved by Steven Husted, Professor, Economics, University of Pittsburgh Thomas Rawski, Professor, Economics, University of Pittsburgh James Burnham, Professor, School of Business, Duquesne University Thesis Director: Werner Troesken, Professor, Economics, University of Pittsburgh ii ONCE BITTEN, TWICE SHY: RETHINKING THE FEDERAL RESERVE’S INDEPENDENCE AND MONETARY POLICY IN THE U.S. Niveditha Prabakaran, B.Phil University of Pittsburgh, 2011 Copyright © by Niveditha Prabakaran 2011 iii Once Bitten, Twice shy: Rethinking the Federal Reserve’s Independence and Monetary Policy in the U.S. Niveditha Prabakaran, B.Phil University of Pittsburgh, 2011 It is widely believed that the Federal Reserve played a central role in bringing about the biggest catastrophe in American history—the Great Depression. The literature is extensive in seeking to provide an explanation for the Federal Reserve’s policy errors. This paper offers a new interpretation on why such an event occurred by studying a heretofore-unexamined landmark court case. In 1928, a private citizen filed suit against the Federal Reserve Bank of New York for increasing discount rates; he sough a court injunction that would force the Federal Reserve to decrease rates.