FDIC Banking Review, Vol. 17, No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Option in Housing Finance

The Public Option in Housing Finance Adam J. Levitin†* and Susan M. Wachter** The U.S. housing finance system presents a conundrum for the scholar of regulation because it defies description using the traditional regulatory vocabulary of command-and-control, taxation, subsidies, cap-and-trade permits, and litigation. Instead, since the New Deal, the housing finance market has been regulated primarily by government participation in the market through a panoply of institutions. The government’s participation in the market has shaped the nature of the products offered in the market. We term this form of regulation “public option” regulation. This Article presents a case study of this “public option” as a regulatory mode. It explains the public option’s rise as a governmental gap-filling response to market failures. The public option, however, took on a life of its own as the federal government undertook financial innovations that the private market had eschewed, in particular the development of the “American mortgage” — a long-term, fixed-rate fully amortizing mortgage. These innovations were trend-setting and set the tone for entire housing finance market, serving as functional regulation. The public option was never understood as a regulatory system due to its ad hoc nature. As a result, its integrity was not protected. Key parts of the system were privatized without a substitution of alternative regulatory measures. The consequence was a return to the very market failures that led to the public option in the first place, followed by another round of ad hoc public options in housing finance. This history suggests that an † Copyright © 2013 Adam J. -

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 83 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1997 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Richard Spillenkothen • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 947 TREASURY AND FEDERAL RESERVE OPEN formance can improve investor and counterparty MARKET OPERATIONS decisions, thus improving market discipline on banking organizations and other companies, During the third quarter of 1997, the dollar before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, appreciated 5.0 percent against the Japanese yen Securities and Government Sponsored Enter- and 0.8 percent against the German mark. On a prises of the House Committee on Banking and trade-weighted basis against other Group of Ten Financial Services, October 1, 1997. currencies, the dollar appreciated 1.4 percent. The U.S. monetary authorities did not undertake 96\ Theodore E. Allison, Assistant to the Board of any intervention in the foreign exchange mar- Governors for Federal Reserve System Affairs, kets during the quarter. reports on the Federal Reserve's plans for deal- ing with some new-design $50 notes that 953 STAFF STUDY SUMMARY were imperfectly printed, including the Federal Reserve's view of the quality and quantity of In The Cost of Implementing Consumer Finan- $50 notes currently being produced by the cial Regulations, the authors present results for Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the options U.S. -

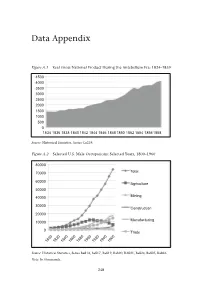

Data Appendix

Data Appendix Figure A.1 Real Gross National Product During the Antebellum Era: 1834–1859 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1834 1836 1838 1840 1842 1844 1846 1848 1850 1852 1854 18561858 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ca219. Figure A.2 Selected U.S. Male Occupations: Selected Years, 1800–1960 80000 70000 Total 60000 Agriculture 50000 40000 Mining 30000 Construction 20000 Manufacturing 10000 0 Trade 1800 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ba814, Ba817, Ba819, Ba820, BA821, Ba824, Ba825, Ba826. Note: In thousands. 248 Source Source Note Source Figure A.5 Figure A.4 Figure A.3 : ThisistheSchwert’sIndexofCommonStock. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesAa36,Aa46, Aa56. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCh411. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCj979. 100000000 150000000 200000000 250000000 300000000 100000 120000 10 12 14 16 50000000 20000 40000 60000 80000 0 2 4 6 8 0 1802 0 U.S. PopulationforSelectedYears:1790–1990 Total NumberofU.S.BusinessFailures:1857–1997 1805 Stock IndexDuringtheAntebellumEra:1802–1870 1857 1790 1830 1860 1890 1920 1950 1990 1808 1863 1869 1811 1875 1814 1881 1817 1887 1820 1893 1823 1899 1826 1905 1829 1911 1832 1917 1835 1923 1838 1929 1841 1935 1941 1844 1947 1847 1953 1850 1959 1853 Total RuralPopulation Total UrbanPopulation Total Population Total 1965 1856 Data Appendix 1971 1859 1977 1862 1983 1865 1989 1995 1868 249 Note Source Note Source Figure A.8 up totheGreatDepression:1869–1929 Figure A.7 250 Source: Figure A.6 : ThisistheIndustrialsIndex. : ThisdataisfromGallman-Kuznetsestimationandin1929dollars. -

The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E

Maryland Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 3 Article 3 Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E. Willis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Banking and Finance Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Lauren E. Willis, Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price, 65 Md. L. Rev. 707 (2006) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARYLAND LAW REVIEW VOLUME 65 2006 NUMBER 3 © Copyright Maryland Law Review 2006 Articles DECISIONMAKING AND THE LIMITS OF DISCLOSURE: THE PROBLEM OF PREDATORY LENDING: PRICE LAUREN E. WILLIS* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 709 I. PREDATORY LENDING AND THE HOME LOAN MARKET ...... 715 A. The Home Lending Revolution ........................ 715 1. The Twentieth Century Marketplace: Standardized Terms, Limited and Advertised Prices, and Low Risk. 715 2. The Brave New World of ProliferatingProducts, Price, and R isk ........................................ 718 3. Evidence of Predatory Home Lending ............... 729 B. A New Definition of Predatory Lending ................. 735 II. FEDERAL LAW REGULATING THE PRICING OF HOME- SECURED LOANS: DISCLOSURE AS PANACEA ................ 741 A. The Rational Actor Decisionmaker Model ............... 741 B. CurrentFederal Law .................................. 743 C. Even a Rational Actor Could Not Use the Federal Disclosures to Price Shop in Today's Marketplace ....... -

The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 159–181 The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed Robert L. Hetzel ilton Friedman (1982, 103) wrote: “In our book on U.S. mon- etary history, Anna Schwartz and I found it possible to use M one sentence to describe the central principle followed by the Federal Reserve System from the time it began operations in 1914 to 1952. That principle, to quote from our book, is: ‘Ifthe ‘money market’ is properly managed so as to avoid the unproductive use of credit and to assure the availability of credit for productive use, then the money stock will take care of itself.’” For Friedman, the reference to “the money stock”was synonymous with “the price level.”1 How did American monetary experience and debate in the 19th century give rise to these “real bills” views as a guide to Fed policy in the pre-World War II period? As distilled in the real bills doctrine, the founders of the Fed under- stood the Federal Reserve System as a decentralized system of reserve depositories that would allow the expansion and contraction of currency and credit based on discounting member-bank paper that originated out of productive activity. By discounting these “real bills,”the short- term loans that …nanced trade and goods in the process of production, policymakers ful…lled their responsibilities as they understood them. That is, they would provide the reserves required to accommodate the “legitimate,” nonspeculative, demands for credit.2 In so doing, they The author acknowledges helpful comments from Huberto Ennis, Motoo Haruta, Gary Richardson, Robert Sharp, Kurt Schuler, Ellis Tallman, and Alexander Wolman. -

Central Banking in the United States: a Fragile Commitment to Price Stability and Independence

Contents ~ Foreword ~ Central Banking in the United States: A Fragile Commitment to Price Stability and Independence ~ Comparative Financial Statements ~ Directors ~ Officers Forevvord ~ ineteen ninety-one was a year of changes policy adjustments-and there will doubtless be and often the changes took unexpected turns. many - should focus on this goal. The long-awaited bank reform bill was passed, but disappointed many in its lack of vision. The Twenty-three directors, representing banking, economy, which many observers expected to business, agriculture, consumer, and labor inter recover, seemed to stall and then founder at the ests, guide the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland close of the year. and its Branches. Their contributions are highly valued, as is the participation of our Small Bank At the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, and Small Business Advisory Councils. change also occurred with the departure of our president, W Lee Hoskins, and the appointment Special thanks are extended to those directors of our new president, Jerry L. Jordan. who have completed their terms of service on our boards. We are especially grateful for the leader Lee, who left to become president and chief ship of Kate Ireland (national chairman, Frontier executive officer of The Huntington National Nursing Service of Wendover, Kentucky), who Bank, made noteworthy contributions on several was chairman of our Cincinnati Branch board fronts. He developed influential public policy of directors. We also appreciate the contributions positions on the importance of price stability of Allen L. Davis (president and chief executive and financial regulatory reform. Under his officer of The Provident Bank, Cincinnati, Ohio), leadership, the Fourth District made signifi who served on our Cincinnati Branch board; and cant progress toward becoming the lowest-cost E. -

The National Monetary Commission: American Banking’S Debt to Europe

1 The National Monetary Commission: American Banking’s Debt to Europe Zack Saravay Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor: Professor Katherine Benton-Cohen Honors Program Chairs: Professors Amy Leonard and Katherine Benton-Cohen 8 May 2017 2 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................ 3 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 HISTORIOGRAPHICAL REVIEW .................................................................................................................. 6 Creation of the Federal Reserve ........................................................................................................... 7 Progressive Era Economics ................................................................................................................ 13 BACKGROUND – THE NATIONAL BANKING SYSTEM (1863-1908) ......................................................... 15 CHAPTER I. ORIGINS OF THE NMC (1908) ...................................................................................... 25 THE BATTLE FOR CURRENCY REFORM ................................................................................................... 25 THE ALDRICH-VREELAND ACT ............................................................................................................... 28 COMPOSITION AND SCOPE OF -

1. What Is the Title of Colonel Harland Sanders' Autobiography?

1. What is the title of Colonel Harland Sanders’ autobiography? Ans - Finger Lickin' Good 2. FACUNDO DA ______ gave the world which Brand? Ans – Bacardi 3. Which company's name is derived from Voice Data & Phone? Ans – Vodafone 4. Which airlines parent company is called Interglobe Airlines? Ans – Indigo 5. Which entertainment company publishes an annual report called 'KIDSENSE'? Ans – Disney 6. Which beverage giant gives out 'Wodruff Awards' annually? Ans – Coca-Cola 7. Which Microsoft hardware product, launched in 2000, was created by Seamus Blackley and Kevin Bachus ? Ans – XBOX 8. "Interpret the world" is the tagline of which magazine? Ans – The Economist 9. Which brand of tea is named after its founders Mallik and Dilhan? Ans – Dilmah Tea 10. What is Bacon mail? Ans – Mail for which you have subscribed but get filtered as SPAM 11. Which Hasbro toy line, manufactured by Takara Tomy, is divided into heroic autobots and evil decepticones? Ans - Transformers 12. Which R&D organisation started Projects Garuda, Setu, Veda, Vyasa, Vidwan, Vidur? Ans - Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DAC) 13. Who authored the book, “India: From Midnight to the Millennium” in 1997? Ans – Shashi Tharoor 14. Which Padma Vibhushan awardee was the editor of Fortune magazine from 1943-48? Ans - John Kenneth Galbraith 15. If Michelle Obama is one of the two US first ladies to feature on the cover of Vogue, name the other one? Ans – Hillary Clinton 16. Which US director agreed to an out of court 5 Million dollar settlement with an apparel company for using his picture in their ads? Ans – Woody Allen 17. -

Central Bank Activism Duke Law Journal, Vol

Central Bank Activism Duke Law Journal, Vol. 71: __ (forthcoming) Christina Parajon Skinner † ABSTRACT—Today, the Federal Reserve is at a critical juncture in its evolution. Unlike any prior period in U.S. history, the Fed now faces increasing demands to expand its policy objectives to tackle a wide range of social and political problems—including climate change, income and racial inequality, and foreign and small business aid. This Article develops a framework for recognizing, and identifying the problems with, “central bank activism.” It refers to central bank activism as situations in which immediate public policy problems push central banks to aggrandize their power beyond the text and purpose of their legal mandates, which Congress has established. To illustrate, the Article provides in-depth exploration of both contemporary and historic episodes of central bank activism, thus clarifying the indicia of central bank activism and drawing out the lessons that past episodes should teach us going forward. The Article urges that, while activism may be expedient in the near term, there are long-term social costs. Activism undermines the legitimacy of central bank authority, erodes its political independence, and ultimately renders a weaker central bank. In the end, the Article issues an urgent call to resist the allure of activism. And it places front and center the need for vibrant public discourse on the role of a central bank in American political and economic life today. © 2021 Christina Parajon Skinner. Draft 2021-05-27 20:46. † Assistant Professor, The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. This article benefited from feedback provided by workshop or conference participants at The Wharton School, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York . -

By:Bill Medley

By: Bill Medley Highways of Commerce Central Banking and The U.S. Payments System By: Bill Medley Highways of Commerce Central Banking and The U.S. Payments System Published by the Public Affairs Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City 1 Memorial Drive • Kansas City, MO 64198 Diane M. Raley, publisher Lowell C. Jones, executive editor Bill Medley, author Casey McKinley, designer Cindy Edwards, archivist All rights reserved, Copyright © 2014 Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the publisher. First Edition, July 2014 The Highways of Commerce • III �ontents Foreword VII Chapter One A Calculus of Chaos: Commerce in Early America 1 Chapter Two “Order out of Confusion:” The Suffolk Bank 7 Chapter Three “A New Era:” The Clearinghouse 19 Chapter Four “A Famine of Currency:” The Panic of 1907 27 Chapter Five “The Highways of Commerce:” The Road to a Central Bank 35 Chapter Six “A problem…of great novelty:” Building a New Clearing System 45 Chapter Seven Bank Robbers and Bolsheviks: The Par Clearance Controversy 55 Chapter Eight “A Plump Automatic Bookkeeper:” The Rise of Banking Automation 71 Chapter Nine Control and Competition: The Monetary Control Act 83 Chapter Ten The Fed’s Air Force: A Plan for the Future 95 Chapter Eleven Disruption and Evolution: The Development of Check 21 105 Chapter Twelve Banks vs. Merchants: The Durbin Amendment 113 Afterword The Path Ahead 125 Endnotes 128 Sources and Selected Bibliography 146 Photo Credits 154 Index 160 Contents • V ForewordAs Congress undertook the task of designing a central bank for the United States in 1913, it was clear that lawmakers intended for the new institution to play a key role in improving the performance of the nation’s payments system. -

THE WORLD of COINS an Introduction to Numismatics

THE WORLD OF COINS An Introduction to Numismatics Jeff Garrett Table of Contents The World of Coins .................................................... Page 1 The Many Ways to Collect Coins .............................. Page 4 Series Collecting ........................................................ Page 6 Type Collecting .......................................................... Page 8 U.S. Proof Sets and Mint Sets .................................... Page 10 Commemorative Coins .............................................. Page 16 Colonial Coins ........................................................... Page 20 Pioneer Gold Coins .................................................... Page 22 Pattern Coins .............................................................. Page 24 Modern Coins (Including Proofs) .............................. Page 26 Silver Eagles .............................................................. Page 28 Ancient Coins ............................................................. Page 30 World Coins ............................................................... Page 32 Currency ..................................................................... Page 34 Pedigree and Provenance ........................................... Page 40 The Rewards and Risks of Collecting Coins ............. Page 44 The Importance of Authenticity and Grade ............... Page 46 National Numismatic Collection ................................ Page 50 Conclusion ................................................................. Page -

Economic Development Institute of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized

0i"n Economic Development Institute of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized venting Bank -C- se: aLessons-- fr-Rn R-ecn Global Public Disclosure Authorized B n0hk: FailuWres:: --: 0~ :B-- -0\ 3 Sept. 1q9q -Ger rd Cpr, Jr.- Public Disclosure Authorized Wil ja C. Hunter Dafly M.Leipziger -T-I -~D XIEVELO}PMENTD -STUIES--- - Public Disclosure Authorized Other EDI Development Studies (In orderof publication) Ente?priseRestructuringandUnemploymentinModelsofTransition Edited by Simon Commander PovertyinRussia:PublicPolicyandPnvateResponses Edited by jeni Klugman EnterpriseRestructuyingandEconomicPolicyinRussia Edited by Simon Commander, Qimiao Fan, and Mark E. Schaffer InfrastructureDelivery:PrivateInitiativeandthePublicGood Edited by Ashoka Mody Trade,Technology,andInternationalCompetitiveness Irfan ul Haque CorporateGovernance in TransitionalEconomies: InsiderControlandtheRole ofBanks Edited by Masahiko Aoki and Hyung-Ki Kim Unemployment,Restructunng,andtheLaborMarket in EasternEuropeandRussia Edited by Simon Commander and Fabrizio Coricelli MonitoringandEvaluatingSocialProgramsinDevelopingCountries: A HandbookforPolicymakers,Managers,andResearchers Joseph Valadez and Michael Bamberger AgroindustrialInvestmentandOperations James G. Brown with Deloitte & Touche LaborMdarketsin an EraofAdjustment Edited by Susan Horton, Ravi Kanbur, and Dipak Mazumdar Vol. 1-IssuesPapers; Vol. 2-CaseStudies DoesPrivatizationDeliver?Highlightsfrom a WorldBankConference Edited by Ahmed Galal and Mary Shirley 7heAdaptiveEconomy:AdjustmentPolicies inSmall,Low-IncomeCountries