Central Banking in the United States: a Fragile Commitment to Price Stability and Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Option in Housing Finance

The Public Option in Housing Finance Adam J. Levitin†* and Susan M. Wachter** The U.S. housing finance system presents a conundrum for the scholar of regulation because it defies description using the traditional regulatory vocabulary of command-and-control, taxation, subsidies, cap-and-trade permits, and litigation. Instead, since the New Deal, the housing finance market has been regulated primarily by government participation in the market through a panoply of institutions. The government’s participation in the market has shaped the nature of the products offered in the market. We term this form of regulation “public option” regulation. This Article presents a case study of this “public option” as a regulatory mode. It explains the public option’s rise as a governmental gap-filling response to market failures. The public option, however, took on a life of its own as the federal government undertook financial innovations that the private market had eschewed, in particular the development of the “American mortgage” — a long-term, fixed-rate fully amortizing mortgage. These innovations were trend-setting and set the tone for entire housing finance market, serving as functional regulation. The public option was never understood as a regulatory system due to its ad hoc nature. As a result, its integrity was not protected. Key parts of the system were privatized without a substitution of alternative regulatory measures. The consequence was a return to the very market failures that led to the public option in the first place, followed by another round of ad hoc public options in housing finance. This history suggests that an † Copyright © 2013 Adam J. -

GPRA, Planning Document, 2008-2011

BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM GOVERNMENT PERFORMANCE AND RESULTS ACT STRATEGIC PLANNING DOCUMENT 2008-2011 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 1 MISSION ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 VALUES ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS........................................................................................................................................................ 1 ACHIEVEMENT OF GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................... 2 Background........................................................................................................................................... 2 PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS...................................................................................................................... 3 Strategic Planning and the Budgeting Process..................................................................................... 3 Planning Background ........................................................................................................................... 3 MONETARY POLICY FUNCTION......................................................................................................... -

The Employment Act of 1946: a Half Century of Experience

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Policy Brief 169 4-1-1996 The Employment Act of 1946: A Half Century of Experience Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L., "The Employment Act of 1946: A Half Century of Experience", Policy Brief 169, 1996, doi:10.7936/K7571960. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/143. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. NOT FOR RELEASE BEFORE 2:00 E.S.T. APRIL 26, 1996 Center for the Study of The Employment Act of 1946: American A Half Century of Experience Business Murray_Weidenbaum C918 Policy Brief 169 April 1996 Contact: Robert Batterson Communications Director (314) 935-5676 Washington University Campus Box 120B One Brookings Drive St. Louis. Missouri 63130-4899 The Employment Act of 1946: A Half Century of Experience by Murray Weidenbaum The first half century of experience under the Employment Act of 1946 (originally the Full Employment Bill of 1945) likely has disappointed both the proponents and the opponents of that innovative law. The impact on national economic policy is neither as bad as the opposition feared nor as substantial as the sponsors had hoped. -

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 83 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1997 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Richard Spillenkothen • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 947 TREASURY AND FEDERAL RESERVE OPEN formance can improve investor and counterparty MARKET OPERATIONS decisions, thus improving market discipline on banking organizations and other companies, During the third quarter of 1997, the dollar before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, appreciated 5.0 percent against the Japanese yen Securities and Government Sponsored Enter- and 0.8 percent against the German mark. On a prises of the House Committee on Banking and trade-weighted basis against other Group of Ten Financial Services, October 1, 1997. currencies, the dollar appreciated 1.4 percent. The U.S. monetary authorities did not undertake 96\ Theodore E. Allison, Assistant to the Board of any intervention in the foreign exchange mar- Governors for Federal Reserve System Affairs, kets during the quarter. reports on the Federal Reserve's plans for deal- ing with some new-design $50 notes that 953 STAFF STUDY SUMMARY were imperfectly printed, including the Federal Reserve's view of the quality and quantity of In The Cost of Implementing Consumer Finan- $50 notes currently being produced by the cial Regulations, the authors present results for Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the options U.S. -

Jobs and Stable Prices

The Federal Reserve Takes an Active Hand in Fostering Jobs and Stable Prices KEY POINTS After the gold standard was abandoned, it took some time for economists and policymakers to settle on the Federal Reserve’s official objectives and the best way to accomplish them. Keynesian and monetarist schools offered competing visions of what economic policy could achieve. Learning from advancements in economic theory, the Federal Reserve has grown more practiced in conducting countercyclical monetary policy—smoothing out business-cycle fluctuations—to achieve its dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment. The demise of the gold standard as the “North Star” Keynesian economics’ impact was swift and profound. for monetary policy created a vacuum: If the Federal It taught that governments’ monetary and fiscal policies Reserve no longer aimed to maintain a fixed exchange could be designed to smooth out business-cycle fluctua- rate between the US dollar and gold, what should guide tions and promote full employment—without causing its monetary policy decisions? excessive inflation. Moreover, Keynesians de-emphasized the role of monetary policy in the inflation process. The ideas behind the eventually formalized objectives of the Federal Reserve took shape in the 30 years after Keynesian policies’ newfound influence was evident in World War II. At the time, policymakers were rightly the 1960s. The government cut taxes and simultaneously concerned that millions of soldiers were returning home stepped up spending on programs to address poverty with no job prospects, especially given that military and outfit the military. As a result, unemployment stayed production was set to decline sharply. -

Conduct of Monetary Policy: Goals and Targets

Chapter 18 Conduct of Monetary Policy: Goals and Targets PREVIEW Now that we understand the tools that central banks like the Federal Reserve use to conduct monetary policy, we can proceed to how monetary policy is actually con- ducted. Understanding the conduct of monetary policy is important, because it not only affects the money supply and interest rates but also has a major influence on the level of economic activity and hence on our well-being. To explore this subject, we look at the goals that the Fed establishes for monetary policy and its strategies for attaining them. After examining the goals and strategies, we can evaluate the Fed’s conduct of monetary policy in the past, with the hope that it will give us some clues to where monetary policy may head in the future. Goals of Monetary Policy www.federalreserve.gov/pf Six basic goals are continually mentioned by personnel at the Federal Reserve and /pf.htm other central banks when they discuss the objectives of monetary policy: (1) high Review what the Federal employment, (2) economic growth, (3) price stability, (4) interest-rate stability, (5) Reserve reports as its primary purposes and functions. stability of financial markets, and (6) stability in foreign exchange markets. High Employment The Employment Act of 1946 and the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978 (more commonly called the Humphrey-Hawkins Act) commit the U.S. govern- ment to promoting high employment consistent with a stable price level. High employment is a worthy goal for two main reasons: (1) the alternative situation—high unemployment—causes much human misery, with families suffering financial dis- tress, loss of personal self-respect, and increase in crime (though this last conclusion is highly controversial), and (2) when unemployment is high, the economy has not only idle workers but also idle resources (closed factories and unused equipment), resulting in a loss of output (lower GDP). -

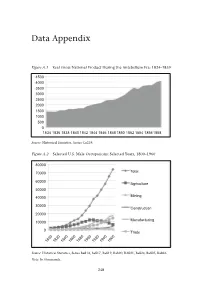

Data Appendix

Data Appendix Figure A.1 Real Gross National Product During the Antebellum Era: 1834–1859 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1834 1836 1838 1840 1842 1844 1846 1848 1850 1852 1854 18561858 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ca219. Figure A.2 Selected U.S. Male Occupations: Selected Years, 1800–1960 80000 70000 Total 60000 Agriculture 50000 40000 Mining 30000 Construction 20000 Manufacturing 10000 0 Trade 1800 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ba814, Ba817, Ba819, Ba820, BA821, Ba824, Ba825, Ba826. Note: In thousands. 248 Source Source Note Source Figure A.5 Figure A.4 Figure A.3 : ThisistheSchwert’sIndexofCommonStock. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesAa36,Aa46, Aa56. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCh411. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCj979. 100000000 150000000 200000000 250000000 300000000 100000 120000 10 12 14 16 50000000 20000 40000 60000 80000 0 2 4 6 8 0 1802 0 U.S. PopulationforSelectedYears:1790–1990 Total NumberofU.S.BusinessFailures:1857–1997 1805 Stock IndexDuringtheAntebellumEra:1802–1870 1857 1790 1830 1860 1890 1920 1950 1990 1808 1863 1869 1811 1875 1814 1881 1817 1887 1820 1893 1823 1899 1826 1905 1829 1911 1832 1917 1835 1923 1838 1929 1841 1935 1941 1844 1947 1847 1953 1850 1959 1853 Total RuralPopulation Total UrbanPopulation Total Population Total 1965 1856 Data Appendix 1971 1859 1977 1862 1983 1865 1989 1995 1868 249 Note Source Note Source Figure A.8 up totheGreatDepression:1869–1929 Figure A.7 250 Source: Figure A.6 : ThisistheIndustrialsIndex. : ThisdataisfromGallman-Kuznetsestimationandin1929dollars. -

The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E

Maryland Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 3 Article 3 Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E. Willis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Banking and Finance Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Lauren E. Willis, Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price, 65 Md. L. Rev. 707 (2006) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARYLAND LAW REVIEW VOLUME 65 2006 NUMBER 3 © Copyright Maryland Law Review 2006 Articles DECISIONMAKING AND THE LIMITS OF DISCLOSURE: THE PROBLEM OF PREDATORY LENDING: PRICE LAUREN E. WILLIS* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 709 I. PREDATORY LENDING AND THE HOME LOAN MARKET ...... 715 A. The Home Lending Revolution ........................ 715 1. The Twentieth Century Marketplace: Standardized Terms, Limited and Advertised Prices, and Low Risk. 715 2. The Brave New World of ProliferatingProducts, Price, and R isk ........................................ 718 3. Evidence of Predatory Home Lending ............... 729 B. A New Definition of Predatory Lending ................. 735 II. FEDERAL LAW REGULATING THE PRICING OF HOME- SECURED LOANS: DISCLOSURE AS PANACEA ................ 741 A. The Rational Actor Decisionmaker Model ............... 741 B. CurrentFederal Law .................................. 743 C. Even a Rational Actor Could Not Use the Federal Disclosures to Price Shop in Today's Marketplace ....... -

The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 159–181 The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed Robert L. Hetzel ilton Friedman (1982, 103) wrote: “In our book on U.S. mon- etary history, Anna Schwartz and I found it possible to use M one sentence to describe the central principle followed by the Federal Reserve System from the time it began operations in 1914 to 1952. That principle, to quote from our book, is: ‘Ifthe ‘money market’ is properly managed so as to avoid the unproductive use of credit and to assure the availability of credit for productive use, then the money stock will take care of itself.’” For Friedman, the reference to “the money stock”was synonymous with “the price level.”1 How did American monetary experience and debate in the 19th century give rise to these “real bills” views as a guide to Fed policy in the pre-World War II period? As distilled in the real bills doctrine, the founders of the Fed under- stood the Federal Reserve System as a decentralized system of reserve depositories that would allow the expansion and contraction of currency and credit based on discounting member-bank paper that originated out of productive activity. By discounting these “real bills,”the short- term loans that …nanced trade and goods in the process of production, policymakers ful…lled their responsibilities as they understood them. That is, they would provide the reserves required to accommodate the “legitimate,” nonspeculative, demands for credit.2 In so doing, they The author acknowledges helpful comments from Huberto Ennis, Motoo Haruta, Gary Richardson, Robert Sharp, Kurt Schuler, Ellis Tallman, and Alexander Wolman. -

January 2020 Dear Investor, in the Annals of Market History, This Past Year May End up Being Discussed Alongside Two Other Infam

January 2020 Dear Investor, In the annals of market history, this past year may end up being discussed alongside two other infamous years ending in the number nine. In 1929, the stock market zoomed higher in a parabolic crescendo to a then unprecedented valuation, while measures of manufacturing and other economic indicators began crumbling underneath. It was a classic example of the final stages of a market mania detaching itself from a diverging economic reality. In 1999, a similar detachment took place, as the market defied all prior bounds of conventional value, leaving behind such simple concepts as real earnings, as technology stocks soared into the stratosphere. These were classic bubbles, but they only appear that way when looked at through the mists of time. In the heat of the moment, with prices rising, rising some more, and then shooting ever higher with abandon, it appeared that the traditional ways of assessing investment value had lost their relevance — a new era had dawned, and investors clamored to claim a piece of that new era before it was too late. Markets become overvalued when there is a convincing story to draw them ever higher, but bubbles occur when such a compelling storyline is accompanied by an extra ingredient — a monetary one. The roaring 1920s witnessed dizzying technological change, which fueled investors’ wild imaginations; it was the decade that saw automobiles, airplanes, radios and refrigerators spread throughout the country. And as you know, the 1990s was also a decade of rapid technological change, and it fueled a similar explosion of investors’ fantasy. -

Insights from the Federal Reserve's Weekly Balance Sheet, 1942-1975

SAE./No.104/May 2018 Studies in Applied Economics INSIGHTS FROM THE FEDERAL RESERVE'S WEEKLY BALANCE SHEET, 1942-1975 Cecilia Bao and Emma Paine Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise Insights from the Federal Reserve’s Weekly Balance Sheet, 1942 -1975 By Cecilia Bao and Emma Paine Copyright 2017 by Cecilia Bao and Emma Paine. This work may be reproduced or adapted provided that no fee is charged and the original source is properly credited. About the Series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise ([email protected]). The authors are mainly students at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Some performed their work as research assistants at the Institute. About the Authors Cecilia Bao ([email protected]) and Emma Paine ([email protected]) are students at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Cecilia is a sophomore pursuing a degree in Applied Math and Statistics, while Emma is a junior studying Economics. They wrote this paper as undergraduate researchers at the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise during Fall 2017. Emma and Cecilia will graduate in May 2019 and May 2020, respectively. Abstract We present digitized data of the Federal Reserve System’s weekly balance sheet from 1942- 1975 for the first time. Following a brief account of the central bank during this period, we analyze the composition and trends of Federal Reserve assets and liabilities, with particular emphasis on how they were affected by significant events during the period. -

Report to the President on the Activities of the Council of Economic Advisers During 2011

APPENDIX A REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COUNCIL OF ECONOMIC ADVISERS DURING 2011 letter of transmittal Council of Economic Advisers Washington, D.C., December 31, 2011 Mr. President: The Council of Economic Advisers submits this report on its activities during calendar year 2011 in accordance with the requirements of the Congress, as set forth in section 10(d) of the Employment Act of 1946 as amended by the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978. Sincerely, Alan B. Krueger, Chairman Katharine G. Abraham, Member Carl Shapiro, Member Activities of the Council of Economic Advisers During 2011 | 295 Council Members and Their Dates of Service Name Position Oath of office date Separation date Edwin G. Nourse Chairman August 9, 1946 November 1, 1949 Leon H. Keyserling Vice Chairman August 9, 1946 Acting Chairman November 2, 1949 Chairman May 10, 1950 January 20, 1953 John D. Clark Member August 9, 1946 Vice Chairman May 10, 1950 February 11, 1953 Roy Blough Member June 29, 1950 August 20, 1952 Robert C. Turner Member September 8, 1952 January 20, 1953 Arthur F. Burns Chairman March 19, 1953 December 1, 1956 Neil H. Jacoby Member September 15, 1953 February 9, 1955 Walter W. Stewart Member December 2, 1953 April 29, 1955 Raymond J. Saulnier Member April 4, 1955 Chairman December 3, 1956 January 20, 1961 Joseph S. Davis Member May 2, 1955 October 31, 1958 Paul W. McCracken Member December 3, 1956 January 31, 1959 Karl Brandt Member November 1, 1958 January 20, 1961 Henry C. Wallich Member May 7, 1959 January 20, 1961 Walter W.