By:Bill Medley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

3i'R 317.3M31 H41 A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of IVIassachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1839amer MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND mmwo states ©alrntiar, 1839. ALSO CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LORING, 13 2 Washington Street. ECLIPSES IN 1839. 1. The first will be a great and total eclipse, on Friday March 15th, at 9h. 28m. morning, but by reason of the moon's south latitude, her shadow will not touch any part of North America. The course of the general eclipse will be from southwest to north- east, from the Pacific Ocean a little west of Chili to the Arabian Gulf and southeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The termination of this grand and sublime phenomenon will probably be witnessed from the summit of some of those stupendous monuments of ancient industry and folly, the vast and lofty pyramids on the banks of the Nile in lower Egypt. The principal cities and places that will be to- tally shadowed in this eclipse, are Valparaiso, Mendoza, Cordova, Assumption, St. Salvador and Pernambuco, in South America, and Sierra Leone, Teemboo, Tombucto and Fezzan, in Africa. At each of these places the duration of total darkness will be from one to six minutes, and several of the planets and fixed stars will probably be visible. 2. The other will also be a grand and beautiful eclipse, on Satur- day, September 7th, at 5h. 35m. evening, but on account of the Mnon's low latitude, and happening so late in the afternoon, no part of it will be visible in North America. -

UNIT - I Evolution of Banking (Origin and Development of Banking)

UNIT - I Evolution of Banking (Origin and development of Banking) The evolution of banking can be traced back to the early times of human history. The history of banking begins with the first prototype banks of merchants of the ancient world, which made grain loans to farmers and traders who carried goods between cities. This began around 2000 BC in Assyria and Babylonia. In olden times people deposited their money and valuables at temples, as they are the safest place available at that time. The practice of storing precious metals at safe places and loaning money was prevalent in ancient Rome. However modern Banking is of recent origin. The development of banking from the traditional lines to the modern structure passes through Merchant bankers, Goldsmiths, Money lenders and Private banks. Merchant Bankers were originally traders in goods. Gradually they started to finance trade and then become bankers. Goldsmiths are considered as the men of honesty, integrity and reliability. They provided strong iron safe for keeping valuables and money. They issued deposit receipts (Promissory notes) to people when they deposit money and valuables with them. The goldsmith paid interest on these deposits. Apart from accepting deposits, Goldsmiths began to lend a part of money deposited with them. Then they became bankers who perform both the basic banking functions such as accepting deposit and lending money. Money lenders were gradually replaced by private banks. Private banks were established in a more organised manner. The growth of Joint stock commercial banking was started only after the enactment of Banking Act 1833 in England. -

The Public Option in Housing Finance

The Public Option in Housing Finance Adam J. Levitin†* and Susan M. Wachter** The U.S. housing finance system presents a conundrum for the scholar of regulation because it defies description using the traditional regulatory vocabulary of command-and-control, taxation, subsidies, cap-and-trade permits, and litigation. Instead, since the New Deal, the housing finance market has been regulated primarily by government participation in the market through a panoply of institutions. The government’s participation in the market has shaped the nature of the products offered in the market. We term this form of regulation “public option” regulation. This Article presents a case study of this “public option” as a regulatory mode. It explains the public option’s rise as a governmental gap-filling response to market failures. The public option, however, took on a life of its own as the federal government undertook financial innovations that the private market had eschewed, in particular the development of the “American mortgage” — a long-term, fixed-rate fully amortizing mortgage. These innovations were trend-setting and set the tone for entire housing finance market, serving as functional regulation. The public option was never understood as a regulatory system due to its ad hoc nature. As a result, its integrity was not protected. Key parts of the system were privatized without a substitution of alternative regulatory measures. The consequence was a return to the very market failures that led to the public option in the first place, followed by another round of ad hoc public options in housing finance. This history suggests that an † Copyright © 2013 Adam J. -

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 83 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1997 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Richard Spillenkothen • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 947 TREASURY AND FEDERAL RESERVE OPEN formance can improve investor and counterparty MARKET OPERATIONS decisions, thus improving market discipline on banking organizations and other companies, During the third quarter of 1997, the dollar before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, appreciated 5.0 percent against the Japanese yen Securities and Government Sponsored Enter- and 0.8 percent against the German mark. On a prises of the House Committee on Banking and trade-weighted basis against other Group of Ten Financial Services, October 1, 1997. currencies, the dollar appreciated 1.4 percent. The U.S. monetary authorities did not undertake 96\ Theodore E. Allison, Assistant to the Board of any intervention in the foreign exchange mar- Governors for Federal Reserve System Affairs, kets during the quarter. reports on the Federal Reserve's plans for deal- ing with some new-design $50 notes that 953 STAFF STUDY SUMMARY were imperfectly printed, including the Federal Reserve's view of the quality and quantity of In The Cost of Implementing Consumer Finan- $50 notes currently being produced by the cial Regulations, the authors present results for Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the options U.S. -

Nonprofit and Mutual Firms in the Development of the U.S. Personal Finance Industry

Organizational Form and Industry Emergence: Nonprofit and Mutual Firms in the Development of the U.S. Personal Finance Industry R. Daniel Wadhwani Eberhardt School of Business University of the Pacific [email protected] This article examines historical variations in the ownership and governance of firms in the U.S. personal finance industry between the early nineteenth century and the Great Depression. It focuses, in particular, on mutual savings banks and their role in the development of the intermediated market for savings accounts. Economic theories of commercial nonprofits and mutuals usually emphasise the advantages of such ownership and governance structures in reducing agency and monitoring costs in markets that suffer from information asymmetries in exchanges between firms and their customers. While I find some evidence to support these theories, I also find that mutual savings banks predominated in the early years of the industry because the form offered entrepreneurial advantages over investor-owned corporations and because in some states they benefitted from regulatory and political advantages that joint-stock savings banks lacked. Their relative decline by the early twentieth century was the result of increasing competition in the market for savings deposits, the loosening of regulatory barriers to entry, and changes in public policy that reduced the transaction, innovation and regulatory advantages that the mutual savings bank form had once held. The article draws out the theoretical implications for our understanding of the historical role of nonprofit and mutual firms. Keywords: nonprofit; trusteeship; mutual; cooperative; savings banks; governance; ownership; organizational form; entrepreneurship; innovation. 1 Introduction In recent years, business historians have devoted increasing attention to understanding variation in the organizational forms of modern enterprise. -

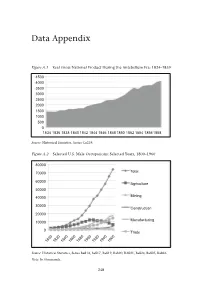

Data Appendix

Data Appendix Figure A.1 Real Gross National Product During the Antebellum Era: 1834–1859 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1834 1836 1838 1840 1842 1844 1846 1848 1850 1852 1854 18561858 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ca219. Figure A.2 Selected U.S. Male Occupations: Selected Years, 1800–1960 80000 70000 Total 60000 Agriculture 50000 40000 Mining 30000 Construction 20000 Manufacturing 10000 0 Trade 1800 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ba814, Ba817, Ba819, Ba820, BA821, Ba824, Ba825, Ba826. Note: In thousands. 248 Source Source Note Source Figure A.5 Figure A.4 Figure A.3 : ThisistheSchwert’sIndexofCommonStock. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesAa36,Aa46, Aa56. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCh411. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCj979. 100000000 150000000 200000000 250000000 300000000 100000 120000 10 12 14 16 50000000 20000 40000 60000 80000 0 2 4 6 8 0 1802 0 U.S. PopulationforSelectedYears:1790–1990 Total NumberofU.S.BusinessFailures:1857–1997 1805 Stock IndexDuringtheAntebellumEra:1802–1870 1857 1790 1830 1860 1890 1920 1950 1990 1808 1863 1869 1811 1875 1814 1881 1817 1887 1820 1893 1823 1899 1826 1905 1829 1911 1832 1917 1835 1923 1838 1929 1841 1935 1941 1844 1947 1847 1953 1850 1959 1853 Total RuralPopulation Total UrbanPopulation Total Population Total 1965 1856 Data Appendix 1971 1859 1977 1862 1983 1865 1989 1995 1868 249 Note Source Note Source Figure A.8 up totheGreatDepression:1869–1929 Figure A.7 250 Source: Figure A.6 : ThisistheIndustrialsIndex. : ThisdataisfromGallman-Kuznetsestimationandin1929dollars. -

New Monetarist Economics: Methods∗

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Research Department Staff Report 442 April 2010 New Monetarist Economics: Methods∗ Stephen Williamson Washington University in St. Louis and Federal Reserve Banks of Richmond and St. Louis Randall Wright University of Wisconsin — Madison and Federal Reserve Banks of Minneapolis and Philadelphia ABSTRACT This essay articulates the principles and practices of New Monetarism, our label for a recent body of work on money, banking, payments, and asset markets. We first discuss methodological issues distinguishing our approach from others: New Monetarism has something in common with Old Monetarism, but there are also important differences; it has little in common with Keynesianism. We describe the principles of these schools and contrast them with our approach. To show how it works, in practice, we build a benchmark New Monetarist model, and use it to study several issues, including the cost of inflation, liquidity and asset trading. We also develop a new model of banking. ∗We thank many friends and colleagues for useful discussions and comments, including Neil Wallace, Fernando Alvarez, Robert Lucas, Guillaume Rocheteau, and Lucy Liu. We thank the NSF for financial support. Wright also thanks for support the Ray Zemon Chair in Liquid Assets at the Wisconsin Business School. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Banks of Richmond, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis, or the Federal Reserve System. 1Introduction The purpose of this essay is to articulate the principles and practices of a school of thought we call New Monetarist Economics. It is a companion piece to Williamson and Wright (2010), which provides more of a survey of the models used in this literature, and focuses on technical issues to the neglect of methodology or history of thought. -

Determinants of Automated Teller Machine Deployment: the Case of Commercial Banks of Ethiopia

DSpace Institution DSpace Repository http://dspace.org Economics Thesis and Dissertations 2020-10-20 Determinants of Automated Teller Machine Deployment: The case of commercial banks of Ethiopia Mahilet Demissie http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/11430 Downloaded from DSpace Repository, DSpace Institution's institutional repository Determinants of Automated Teller Machine Deployment: The case of commercial banks of Ethiopia A Thesis Submitted to Bahir Dar University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Degree of Masters of Science in Accounting and Finance Bahir Dar University College of Business and Economics Department of Accounting and Finance BY: Mahilet Demissie Adane Advisor: Teramaje Wale (Dr.) February, 2018 Bahir Dar, Ethiopia i Statement of declaration This is to certify that the thesis work by Mahilet Demissie entitled as “Determinants of Automated teller machine Deployment in Commercial Banks of Ethiopia”. A Thesis Submitted to Bahir Dar University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Degree of Masters of Science in Accounting and Finance. Compilies with the regulations of the university and meets the accepted standard with respect to originality and quality. Approved by the examining committee Advisor: -------------------------------- Signature-----------------Date-------------------- External Examiner:----------------------Signature ----------------Date----------------- Internal Examiner: -------------------------Signature--------------Date----------------- Chair person :--------------------------------Signature--------------Date--------------- ii Acknowledgement First of all, I would like to thank the Almighty God and his mother for their entire help trough out my life. Next, I would like to thank my advisor Teramaje Wale (Dr.) for his unreserved advice for the completion of this thesis. My grateful thanks also go to National Bank of Ethiopia, head office of each bank for their positive cooperation in giving the relevant data for the study. -

Friday, June 21, 2013 the Failures That Ignited America's Financial

Friday, June 21, 2013 The Failures that Ignited America’s Financial Panics: A Clinical Survey Hugh Rockoff Department of Economics Rutgers University, 75 Hamilton Street New Brunswick NJ 08901 [email protected] Preliminary. Please do not cite without permission. 1 Abstract This paper surveys the key failures that ignited the major peacetime financial panics in the United States, beginning with the Panic of 1819 and ending with the Panic of 2008. In a few cases panics were triggered by the failure of a single firm, but typically panics resulted from a cluster of failures. In every case “shadow banks” were the source of the panic or a prominent member of the cluster. The firms that failed had excellent reputations prior to their failure. But they had made long-term investments concentrated in one sector of the economy, and financed those investments with short-term liabilities. Real estate, canals and railroads (real estate at one remove), mining, and cotton were the major problems. The panic of 2008, at least in these ways, was a repetition of earlier panics in the United States. 2 “Such accidental events are of the most various nature: a bad harvest, an apprehension of foreign invasion, the sudden failure of a great firm which everybody trusted, and many other similar events, have all caused a sudden demand for cash” (Walter Bagehot 1924 [1873], 118). 1. The Role of Famous Failures1 The failure of a famous financial firm features prominently in the narrative histories of most U.S. financial panics.2 In this respect the most recent panic is typical: Lehman brothers failed on September 15, 2008: and … all hell broke loose. -

Banking and Insurance - Should Ever the Twain Meet? Emeric Fischer William & Mary Law School

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1992 Banking and Insurance - Should Ever the Twain Meet? Emeric Fischer William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Fischer, Emeric, "Banking and Insurance - Should Ever the Twain Meet?" (1992). Faculty Publications. 485. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/485 Copyright c 1992 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs Emeric Fischer* Banking and Insurance-Should Ever the Twain Meet? TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction . 727 II. Evolution of Banking in the United States . 731 A. Banking Prior to the Civil War .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 731 1. From the Revolutionary War to 1836 . 731 2. The State Free Banking System, 1837 to 1864 . 733 B. The National Free Banking System, 1864 to 1933 . 734 1. Prior to 1913 . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 734 2. Mter 1913 . 735 III. Regulation of Banking . 737 A. The Glass-Steagall Act and the FDIC . 737 B. Policy Goals of Federal Regulation. 738 1. The Broad Goals . 739 2. General Constraints on Federal Banking Policy . 739 C. The Policy Implementing Tools (Regulatory Mechanisms) . 741 1. Entry Restrictions .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 741 2. Capitalization Requirements..................... 743 3. Limitation of and Prohibition Against Specific Activities. 744 4. Restrictions on Mfiliations and Geographic Expansion . 749 5. Lending and Borrowing Limitations . 750 * R. Hugh and Nolie A. Haynes Professor of Law, William and Mary School of Law. B.S. University of South Carolina 1951; J.D. 1963 and M.L.&T. 1964 College of William and Mary, Marshall-Wythe School of Law. -

Universita' Degli Studi Di Padova

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE ECONOMICHE ED AZIENDALI “M.FANNO” CORSO DI LAUREA MAGISTRALE / SPECIALISTICA IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION TESI DI LAUREA “The American banking system before the FED” RELATORE: CH.MO PROF. GIANFRANCO TUSSET LAUREANDO: CARLO RUBBO MATRICOLA N. 1121213 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016 – 2017 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016 – 2017 Il candidato dichiara che il presente lavoro è originale e non è già stato sottoposto, in tutto o in parte, per il conseguimento di un titolo accademico in altre Università italiane o straniere. Il candidato dichiara altresì che tutti i materiali utilizzati durante la preparazione dell’elaborato sono stati indicati nel testo e nella sezione “Riferimenti bibliografici” e che le eventuali citazioni testuali sono individuabili attraverso l’esplicito richiamo alla pubblicazione originale. Firma dello studente _________________ INDEX INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 2 CHAPTER ONE ........................................................... 4 THE INDEPENDENCE WAR AND THE BANK OF NORTH AMERICA .... 5 THE FIRST BANK OF THE UNITED STATES 1791 – 1811 ........................... 8 THE SECOND BANK OF THE UNITED STATES 1816-1833 ....................... 13 THE DECENTRALIZED BANKING SYSTEM 1837 – 1863 .......................... 17 CIVIL WAR FINANCING AND THE NATIONAL BANKING SYSTEM ... 23 PANICS OF THE END OF THE CENTURY AND ROAD TO THE FED .... 27 CHAPTER TWO ........................................................ 39 THE ROLE OF THE U.S. SUPREME COURT ................................................ 40 THE SUFFOLK SYSTEM: A “FREE MARKET CENTRAL BANK” .......... 45 DO THE U.S. NEED A CENTRALIZED BANKING SYSTEM? ................... 49 FINAL REFLECTIONS ............................................ 64 BIBLIOGRAPHY ....................................................... 69 1 INTRODUCTION The history of the American banking system is not well-known but it is very important, since it has shaped the current financial market of the country. The U.S. -

TORC3: Token-Ring Clearing Heuristic for Currency Circulation

TORC3: Token-Ring Clearing Heuristic for Currency Circulation Carlos Humes Jr.∗, Marcelo S. Lauretto†, Fábio Nakano†, Carlos A.B. Pereira∗, Guilherme F.G. Rafare∗∗ and Julio M. Stern∗,‡ ∗Institute of Mathematics and Statistics of the University of São Paulo, Brazil †School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities of the University of São Paulo, Brazil ∗∗FinanTech Ltda. ‡[email protected] Abstract. Clearing algorithms are at the core of modern payment systems, facilitating the settling of multilateral credit messages with (near) minimum transfers of currency. Traditional clearing procedures use batch processing based on MILP - mixed-integer linear programming algorithms. The MILP approach demands intensive computational resources; moreover, it is also vulnerable to operational risks generated by possible defaults during the inter-batch period. This paper presents TORC3 - the Token-Ring Clearing Algorithm for Currency Circulation. In contrast to the MILP approach, TORC3 is a real time heuristic procedure, demanding modest computational resources, and able to completely shield the clearing operation against the participating agents’ risk of default. Keywords: Bayesian calibration; Clearing algorithms; Heuristic optimization; Multilateral netting; Operational risk; Payment systems; Real-time heuristic procedures. 1. INTRODUCTION Clearing algorithms are at the core of modern payment systems, facilitating multilat- eral netting, that is, the settling of multilateral credit messages with (near) minimum transfers of currency. Traditional clearing procedures use batch processing based on mixed-integer linear programming algorithms. Large scale mixed-integer programming demands intensive computational resources; most of the traditional clearing algorithms require large mainframe computers. Furthermore, this approach delays all payments to after the batch processing (usually overnight). Moreover, batch processing introduces an operational risk originated from the possibility of a participant’s default in the iter-batch processing period.