The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

3i'R 317.3M31 H41 A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of IVIassachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1839amer MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND mmwo states ©alrntiar, 1839. ALSO CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LORING, 13 2 Washington Street. ECLIPSES IN 1839. 1. The first will be a great and total eclipse, on Friday March 15th, at 9h. 28m. morning, but by reason of the moon's south latitude, her shadow will not touch any part of North America. The course of the general eclipse will be from southwest to north- east, from the Pacific Ocean a little west of Chili to the Arabian Gulf and southeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The termination of this grand and sublime phenomenon will probably be witnessed from the summit of some of those stupendous monuments of ancient industry and folly, the vast and lofty pyramids on the banks of the Nile in lower Egypt. The principal cities and places that will be to- tally shadowed in this eclipse, are Valparaiso, Mendoza, Cordova, Assumption, St. Salvador and Pernambuco, in South America, and Sierra Leone, Teemboo, Tombucto and Fezzan, in Africa. At each of these places the duration of total darkness will be from one to six minutes, and several of the planets and fixed stars will probably be visible. 2. The other will also be a grand and beautiful eclipse, on Satur- day, September 7th, at 5h. 35m. evening, but on account of the Mnon's low latitude, and happening so late in the afternoon, no part of it will be visible in North America. -

Monetary Policy in a World of Cryptocurrencies∗

Monetary Policy in a World of Cryptocurrencies Pierpaolo Benigno University of Bern March 17, 2021 Abstract Can currency competition affect central banks’control of interest rates and prices? Yes, it can. In a two-currency world with competing cash (material or digital), the growth rate of the cryptocurrency sets an upper bound on the nominal interest rate and the attainable inflation rate, if the government cur- rency is to retain its role as medium of exchange. In any case, the government has full control of the inflation rate. With an interest-bearing digital currency, equilibria in which government currency loses medium-of-exchange property are ruled out. This benefit comes at the cost of relinquishing control over the inflation rate. I am grateful to Giorgio Primiceri for useful comments, Marco Bassetto for insightful discussion at the NBER Monetary Economics Meeting and Roger Meservey for professional editing. In recent years cryptocurrencies have attracted the attention of consumers, media and policymakers.1 Cryptocurrencies are digital currencies, not physically minted. Monetary history offers other examples of uncoined money. For centuries, since Charlemagne, an “imaginary” money existed but served only as unit of account and never as, unlike today’s cryptocurrencies, medium of exchange.2 Nor is the coexistence of multiple currencies within the borders of the same nation a recent phe- nomenon. Medieval Europe was characterized by the presence of multiple media of exchange of different metallic content.3 More recently, some nations contended with dollarization or eurization.4 However, the landscape in which digital currencies are now emerging is quite peculiar: they have appeared within nations dominated by a single fiat currency just as central banks have succeeded in controlling the value of their currencies and taming inflation. -

The Public Option in Housing Finance

The Public Option in Housing Finance Adam J. Levitin†* and Susan M. Wachter** The U.S. housing finance system presents a conundrum for the scholar of regulation because it defies description using the traditional regulatory vocabulary of command-and-control, taxation, subsidies, cap-and-trade permits, and litigation. Instead, since the New Deal, the housing finance market has been regulated primarily by government participation in the market through a panoply of institutions. The government’s participation in the market has shaped the nature of the products offered in the market. We term this form of regulation “public option” regulation. This Article presents a case study of this “public option” as a regulatory mode. It explains the public option’s rise as a governmental gap-filling response to market failures. The public option, however, took on a life of its own as the federal government undertook financial innovations that the private market had eschewed, in particular the development of the “American mortgage” — a long-term, fixed-rate fully amortizing mortgage. These innovations were trend-setting and set the tone for entire housing finance market, serving as functional regulation. The public option was never understood as a regulatory system due to its ad hoc nature. As a result, its integrity was not protected. Key parts of the system were privatized without a substitution of alternative regulatory measures. The consequence was a return to the very market failures that led to the public option in the first place, followed by another round of ad hoc public options in housing finance. This history suggests that an † Copyright © 2013 Adam J. -

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 83 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1997 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Richard Spillenkothen • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 947 TREASURY AND FEDERAL RESERVE OPEN formance can improve investor and counterparty MARKET OPERATIONS decisions, thus improving market discipline on banking organizations and other companies, During the third quarter of 1997, the dollar before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, appreciated 5.0 percent against the Japanese yen Securities and Government Sponsored Enter- and 0.8 percent against the German mark. On a prises of the House Committee on Banking and trade-weighted basis against other Group of Ten Financial Services, October 1, 1997. currencies, the dollar appreciated 1.4 percent. The U.S. monetary authorities did not undertake 96\ Theodore E. Allison, Assistant to the Board of any intervention in the foreign exchange mar- Governors for Federal Reserve System Affairs, kets during the quarter. reports on the Federal Reserve's plans for deal- ing with some new-design $50 notes that 953 STAFF STUDY SUMMARY were imperfectly printed, including the Federal Reserve's view of the quality and quantity of In The Cost of Implementing Consumer Finan- $50 notes currently being produced by the cial Regulations, the authors present results for Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the options U.S. -

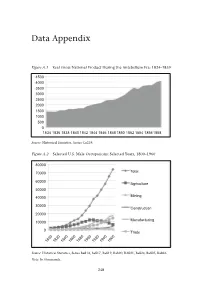

Data Appendix

Data Appendix Figure A.1 Real Gross National Product During the Antebellum Era: 1834–1859 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1834 1836 1838 1840 1842 1844 1846 1848 1850 1852 1854 18561858 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ca219. Figure A.2 Selected U.S. Male Occupations: Selected Years, 1800–1960 80000 70000 Total 60000 Agriculture 50000 40000 Mining 30000 Construction 20000 Manufacturing 10000 0 Trade 1800 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ba814, Ba817, Ba819, Ba820, BA821, Ba824, Ba825, Ba826. Note: In thousands. 248 Source Source Note Source Figure A.5 Figure A.4 Figure A.3 : ThisistheSchwert’sIndexofCommonStock. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesAa36,Aa46, Aa56. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCh411. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCj979. 100000000 150000000 200000000 250000000 300000000 100000 120000 10 12 14 16 50000000 20000 40000 60000 80000 0 2 4 6 8 0 1802 0 U.S. PopulationforSelectedYears:1790–1990 Total NumberofU.S.BusinessFailures:1857–1997 1805 Stock IndexDuringtheAntebellumEra:1802–1870 1857 1790 1830 1860 1890 1920 1950 1990 1808 1863 1869 1811 1875 1814 1881 1817 1887 1820 1893 1823 1899 1826 1905 1829 1911 1832 1917 1835 1923 1838 1929 1841 1935 1941 1844 1947 1847 1953 1850 1959 1853 Total RuralPopulation Total UrbanPopulation Total Population Total 1965 1856 Data Appendix 1971 1859 1977 1862 1983 1865 1989 1995 1868 249 Note Source Note Source Figure A.8 up totheGreatDepression:1869–1929 Figure A.7 250 Source: Figure A.6 : ThisistheIndustrialsIndex. : ThisdataisfromGallman-Kuznetsestimationandin1929dollars. -

The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E

Maryland Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 3 Article 3 Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E. Willis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Banking and Finance Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Lauren E. Willis, Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price, 65 Md. L. Rev. 707 (2006) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARYLAND LAW REVIEW VOLUME 65 2006 NUMBER 3 © Copyright Maryland Law Review 2006 Articles DECISIONMAKING AND THE LIMITS OF DISCLOSURE: THE PROBLEM OF PREDATORY LENDING: PRICE LAUREN E. WILLIS* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 709 I. PREDATORY LENDING AND THE HOME LOAN MARKET ...... 715 A. The Home Lending Revolution ........................ 715 1. The Twentieth Century Marketplace: Standardized Terms, Limited and Advertised Prices, and Low Risk. 715 2. The Brave New World of ProliferatingProducts, Price, and R isk ........................................ 718 3. Evidence of Predatory Home Lending ............... 729 B. A New Definition of Predatory Lending ................. 735 II. FEDERAL LAW REGULATING THE PRICING OF HOME- SECURED LOANS: DISCLOSURE AS PANACEA ................ 741 A. The Rational Actor Decisionmaker Model ............... 741 B. CurrentFederal Law .................................. 743 C. Even a Rational Actor Could Not Use the Federal Disclosures to Price Shop in Today's Marketplace ....... -

86-2 17-37.Pdf

Opinions expressedil'lthe/ nomic Review do not necessarily reflect the vie management of the Federal Reserve BankofSan Francisco, or of the Board of Governors the Feder~1 Reserve System. The FedetaIReserve Bank ofSari Fraricisco's Economic Review is published quarterly by the Bank's Research and Public Information Department under the supervision of John L. Scadding, SeniorVice Presidentand Director of Research. The publication is edited by Gregory 1. Tong, with the assistance of Karen Rusk (editorial) and William Rosenthal (graphics). For free <copies ofthis and otherFederal Reserve. publications, write or phone the Public InfofIllation Department, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, P.O. Box 7702, San Francisco, California 94120. Phone (415) 974-3234. 2 Ramon Moreno· The traditional critique of the "real bills" doctrine argues that the price level may be unstable in a monetary regime without a central bank and a market-determined money supply. Hong Kong's experience sug gests this problem may not arise in a small open economy. In our century, it is generally assumed that mone proposed that the money supply and inflation could tary control exerted by central banks is necessary to successfully be controlled by the market, without prevent excessive money creation and to achieve central bank control ofthe monetary base, as long as price stability. More recently, in the 1970s, this banks limited their credit to "satisfy the needs of assumption is evident in policymakers' concern that trade". financial innovations have eroded monetary con The real bills doctrine was severely criticized on trols. In particular, the proliferation of market the beliefthat it could lead to instability in the price created substitutes for money not directly under the level. -

Friday, June 21, 2013 the Failures That Ignited America's Financial

Friday, June 21, 2013 The Failures that Ignited America’s Financial Panics: A Clinical Survey Hugh Rockoff Department of Economics Rutgers University, 75 Hamilton Street New Brunswick NJ 08901 [email protected] Preliminary. Please do not cite without permission. 1 Abstract This paper surveys the key failures that ignited the major peacetime financial panics in the United States, beginning with the Panic of 1819 and ending with the Panic of 2008. In a few cases panics were triggered by the failure of a single firm, but typically panics resulted from a cluster of failures. In every case “shadow banks” were the source of the panic or a prominent member of the cluster. The firms that failed had excellent reputations prior to their failure. But they had made long-term investments concentrated in one sector of the economy, and financed those investments with short-term liabilities. Real estate, canals and railroads (real estate at one remove), mining, and cotton were the major problems. The panic of 2008, at least in these ways, was a repetition of earlier panics in the United States. 2 “Such accidental events are of the most various nature: a bad harvest, an apprehension of foreign invasion, the sudden failure of a great firm which everybody trusted, and many other similar events, have all caused a sudden demand for cash” (Walter Bagehot 1924 [1873], 118). 1. The Role of Famous Failures1 The failure of a famous financial firm features prominently in the narrative histories of most U.S. financial panics.2 In this respect the most recent panic is typical: Lehman brothers failed on September 15, 2008: and … all hell broke loose. -

US Monetary Policy 1914-1951

Volatile Times and Persistent Conceptual Errors: U.S. Monetary Policy 1914-1951 Charles W. Calomiris * November 2010 Abstract This paper describes the motives that gave rise to the creation of the Federal Reserve System , summarizes the history of Fed monetary policy from its origins in 1914 through the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951, and reviews several of the principal controversies that surround that history. The persistence of conceptual errors in Fed monetary policy – particularly adherence to the “real bills doctrine” – is a central puzzle in monetary history, particularly in light of the enormous costs of Fed failures during the Great Depression. The institutional, structural, and economic volatility of the period 1914-1951 probably contributed to the slow learning process of policy. Ironically, the Fed's great success – in managing seasonal volatility of interest rates by limiting seasonal liquidity risk – likely contributed to its slow learning about cyclical policy. Keywords: monetary policy, Great Depression, real bills doctrine, bank panics JEL: E58, N12, N22 * This paper was presented November 3, 2010 at a conference sponsored by the Atlanta Fed at Jekyll Island, Georgia. It will appear in a 100th anniversary volume devoted to the history of the Federal Reserve System. I thank my discussant, Allan Meltzer, and Michael Bordo and David Wheelock, for helpful comments on earlier drafts. 0 “If stupidity got us into this mess, then why can’t it get us out?” – Will Rogers1 I. Introduction This chapter reviews the history of the early (1914-1951) period of “monetary policy” under the Federal Reserve System (FRS), defined as policies designed to control the overall supply of liquidity in the financial system, as distinct from lender-of-last-resort policies directed toward the liquidity needs of particular financial institutions (which is treated by Bordo and Wheelock 2010 in another chapter of this volume). -

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis In the spring of 1837, people panicked as financial and economic uncer- tainty spread within and between New York, New Orleans, and London. Although the period of panic would dramatically influence political, cultural, and social history, those who panicked sought to erase from history their experiences of one of America’s worst early financial crises. The Many Panics of 1837 reconstructs the period between March and May 1837 in order to make arguments about the national boundaries of history, the role of information in the economy, the personal and local nature of national and international events, the origins and dissemination of economic ideas, and most importantly, what actually happened in 1837. This riveting transatlantic cultural history, based on archival research on two continents, reveals how people transformed their experiences of financial crisis into the “Panic of 1837,” a single event that would serve as a turning point in American history and an early inspiration for business cycle theory. Jessica M. Lepler is an assistant professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. The Society of American Historians awarded her Brandeis University doctoral dissertation, “1837: Anatomy of a Panic,” the 2008 Allan Nevins Prize. She has been the recipient of a Hench Post-Dissertation Fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society, a Dissertation Fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Program in Early American Economy and Society, a John E. Rovensky Dissertation Fellowship in Business History, and a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship from the U.S. -

Financial Panics and Scandals

Wintonbury Risk Management Investment Strategy Discussions www.wintonbury.com Financial Panics, Scandals and Failures And Major Events 1. 1343: the Peruzzi Bank of Florence fails after Edward III of England defaults. 2. 1621-1622: Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire debases coinage during the Thirty Years War 3. 1634-1637: Tulip bulb bubble and crash in Holland 4. 1711-1720: South Sea Bubble 5. 1716-1720: Mississippi Bubble, John Law 6. 1754-1763: French & Indian War (European Seven Years War) 7. 1763: North Europe Panic after the Seven Years War 8. 1764: British Currency Act of 1764 9. 1765-1769: Post war depression, with farm and business foreclosures in the colonies 10. 1775-1783: Revolutionary War 11. 1785-1787: Post Revolutionary War Depression, Shays Rebellion over farm foreclosures. 12. Bank of the United States, 1791-1811, Alexander Hamilton 13. 1792: William Duer Panic in New York 14. 1794: Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania (Gallatin mediates) 15. British currency crisis of 1797, suspension of gold payments 16. 1808: Napoleon Overthrows Spanish Monarchy; Shipping Marques 17. 1813: Danish State Default 18. 1813: Suffolk Banking System established in Boston and eventually all of New England to clear bank notes for members at par. 19. Second Bank of the United States, 1816-1836, Nicholas Biddle 20. Panic of 1819, Agricultural Prices, Bank Currency, and Western Lands 21. 1821: British restoration of gold payments 22. Republic of Poyais fraud, London & Paris, 1820-1826, Gregor MacGregor. 23. British Banking Crisis, 1825-1826, failed Latin American investments, etc., six London banks including Henry Thornton’s Bank and sixty country banks failed. -

Parallel Journeys: Adam Smith and Milton Friedman on the Regulation of Banking

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Rockoff, Hugh Working Paper Parallel journeys: Adam Smith and Milton Friedman on the regulation of banking Working Paper, No. 2010-04 Provided in Cooperation with: Department of Economics, Rutgers University Suggested Citation: Rockoff, Hugh (2010) : Parallel journeys: Adam Smith and Milton Friedman on the regulation of banking, Working Paper, No. 2010-04, Rutgers University, Department of Economics, New Brunswick, NJ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/59460 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu February, 2010 Parallel Journeys: Adam Smith and Milton Friedman on the Regulation of Banking Hugh Rockoff Rutgers University and NBER Department of Economics 75 Hamilton Street New Brunswick NJ 08901 [email protected] 1 Abstract Adam Smith and Milton Friedman are famous for championing Laissez Faire, yet both supported government regulation of the banking system.