The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Option in Housing Finance

The Public Option in Housing Finance Adam J. Levitin†* and Susan M. Wachter** The U.S. housing finance system presents a conundrum for the scholar of regulation because it defies description using the traditional regulatory vocabulary of command-and-control, taxation, subsidies, cap-and-trade permits, and litigation. Instead, since the New Deal, the housing finance market has been regulated primarily by government participation in the market through a panoply of institutions. The government’s participation in the market has shaped the nature of the products offered in the market. We term this form of regulation “public option” regulation. This Article presents a case study of this “public option” as a regulatory mode. It explains the public option’s rise as a governmental gap-filling response to market failures. The public option, however, took on a life of its own as the federal government undertook financial innovations that the private market had eschewed, in particular the development of the “American mortgage” — a long-term, fixed-rate fully amortizing mortgage. These innovations were trend-setting and set the tone for entire housing finance market, serving as functional regulation. The public option was never understood as a regulatory system due to its ad hoc nature. As a result, its integrity was not protected. Key parts of the system were privatized without a substitution of alternative regulatory measures. The consequence was a return to the very market failures that led to the public option in the first place, followed by another round of ad hoc public options in housing finance. This history suggests that an † Copyright © 2013 Adam J. -

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 83 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1997 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Richard Spillenkothen • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 947 TREASURY AND FEDERAL RESERVE OPEN formance can improve investor and counterparty MARKET OPERATIONS decisions, thus improving market discipline on banking organizations and other companies, During the third quarter of 1997, the dollar before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, appreciated 5.0 percent against the Japanese yen Securities and Government Sponsored Enter- and 0.8 percent against the German mark. On a prises of the House Committee on Banking and trade-weighted basis against other Group of Ten Financial Services, October 1, 1997. currencies, the dollar appreciated 1.4 percent. The U.S. monetary authorities did not undertake 96\ Theodore E. Allison, Assistant to the Board of any intervention in the foreign exchange mar- Governors for Federal Reserve System Affairs, kets during the quarter. reports on the Federal Reserve's plans for deal- ing with some new-design $50 notes that 953 STAFF STUDY SUMMARY were imperfectly printed, including the Federal Reserve's view of the quality and quantity of In The Cost of Implementing Consumer Finan- $50 notes currently being produced by the cial Regulations, the authors present results for Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the options U.S. -

Guide to Predatory Lending Occurs When a Mortgage Loan Between and Gets a Fee Or Other Compensation

What is Know the Don’t Predatory Terms Become a Lending? Mortgage Lender: A bank, savings institution, or mortgage company that offers home loans. Victim: Mortgage Broker: An individual or firm that matches borrowers to lenders and loan programs for a fee. Anyone who acts as a go- A Guide to Predatory lending occurs when a mortgage loan between and gets a fee or other compensation. with unwarranted high interest rates and fees is set Annual Percentage Rate (APR): Cost of the credit, which Predatory up to primarily benefit the lender or broker. The includes the interest and all other finance charges. If APR is more Lending loan is not made in the best interest of the borrower, than .75 to 1 percentage point higher than the interest rate you often locks the borrower into unfair loan terms and were quoted, there are significant fees being added to the loan. tends to cause severe financial hardship or default. Points: Fees paid to the lender to obtain the loan. One point is equal to 1% of the loan amount. Points should be paid at the time of the loan. If your lender insists on prepayment of these fees, find To determine if a loan is predatory in nature, ask a new lender or broker. yourself these questions: Prepayment Penalty: Fees required to be paid by you if the Does your past credit history justify the loan is paid off early. Try to avoid any prepayment penalty that lasts more than 3 years or is for more than 1-2% of the loan high rate and fees charged? amount. -

Loan Originator (LO) Compensation II. Purpose, Coverage and Overview; “Loan

Loan Originator (LO) Compensation II. Purpose, Coverage and Overview; “Loan 1 Originator” and “Compensation” Defined Major Components of Rule . Prohibits steering a consumer into a loan that generates greater compensation for the loan originator, unless the consummated loan is in the consumer's interest. Prohibits loan originator compensation based on the terms of a mortgage transaction or a proxy for a transaction term. Prohibits dual compensation (i.e., loan originator being compensated by both the consumer and another person, such as a creditor). Prohibits mandatory arbitration clauses and waivers of certain causes of action. 2 FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION Major Components of Rule Con’t. Prohibits the financing of credit insurance (this prohibition does not include mortgage insurance). Requires depository institutions have written policies and procedures. Imposes qualification requirements on loan originators. Requires name and NMLSR identification information of loan originator with primary responsibility appear on the credit application, note, and security instrument. Permits, within limits, paying loan originators compensation based on profits derived from a bank’s mortgage-related activities. (“bank” includes an affiliate of the bank and/or a business unit within the bank or affiliate). 3 FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION Key Compensation Prohibition No loan originator can receive and no person can pay to a loan originator, directly or indirectly… . Compensation in an amount that is based on terms of transactions (or proxies for terms of transactions): • a single loan originator, or • multiple loan originators (limited exception: some profits- based compensation). 4 FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION Covered Transactions A covered transaction is a consumer- purpose, closed-end transaction secured by a dwelling, whether by a first or subordinate lien. -

Data Appendix

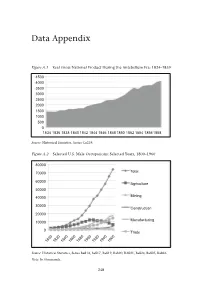

Data Appendix Figure A.1 Real Gross National Product During the Antebellum Era: 1834–1859 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1834 1836 1838 1840 1842 1844 1846 1848 1850 1852 1854 18561858 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ca219. Figure A.2 Selected U.S. Male Occupations: Selected Years, 1800–1960 80000 70000 Total 60000 Agriculture 50000 40000 Mining 30000 Construction 20000 Manufacturing 10000 0 Trade 1800 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ba814, Ba817, Ba819, Ba820, BA821, Ba824, Ba825, Ba826. Note: In thousands. 248 Source Source Note Source Figure A.5 Figure A.4 Figure A.3 : ThisistheSchwert’sIndexofCommonStock. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesAa36,Aa46, Aa56. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCh411. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCj979. 100000000 150000000 200000000 250000000 300000000 100000 120000 10 12 14 16 50000000 20000 40000 60000 80000 0 2 4 6 8 0 1802 0 U.S. PopulationforSelectedYears:1790–1990 Total NumberofU.S.BusinessFailures:1857–1997 1805 Stock IndexDuringtheAntebellumEra:1802–1870 1857 1790 1830 1860 1890 1920 1950 1990 1808 1863 1869 1811 1875 1814 1881 1817 1887 1820 1893 1823 1899 1826 1905 1829 1911 1832 1917 1835 1923 1838 1929 1841 1935 1941 1844 1947 1847 1953 1850 1959 1853 Total RuralPopulation Total UrbanPopulation Total Population Total 1965 1856 Data Appendix 1971 1859 1977 1862 1983 1865 1989 1995 1868 249 Note Source Note Source Figure A.8 up totheGreatDepression:1869–1929 Figure A.7 250 Source: Figure A.6 : ThisistheIndustrialsIndex. : ThisdataisfromGallman-Kuznetsestimationandin1929dollars. -

H0209-I-128.Pdf

Ohio Legislative Service Commission Bill Analysis Daniel M. DeSantis H.B. 209 128th General Assembly (As Introduced) Reps. Lundy, Foley, Murray, Hagan, Phillips, Skindell, Stewart, Harris, Fende, Newcomb, Okey, Celeste, Harwood BILL SUMMARY • Prohibits licensees under the Small Loan Law (R.C. 1321.01 to 1321.19) and registrants under the Mortgage Loan Law (R.C. 1321.51 to 1321.60) from making a loan of $1,000 or less that will obligate the borrower to pay more than 28% APR unless the term of the loan is greater than three months or the loan contract requires three or more installments. • Provides that whoever ʺwillfullyʺ violates the prohibition against loans of $1,000 or less with a 28% APR (1) must forfeit to the borrower twice the amount of interest contracted for (Small Loan Law) or the amount of interest paid by the borrower (Mortgage Loan Law), and (2) will be subject to a fine of not less than $500 nor more than $1,000. • Increases the fine for certain other violations regarding the Mortgage Loan Law of not less than $100 nor more than $500 to not less than $500 nor more than $1,000. • Specifies that the current prohibition on licensees under the Small Loan Law and registrants under the Mortgage Loan Law from conducting business in a place where any ʺother businessʺ is solicited or engaged in if the nature of that business is to conceal evasion of those lending laws, includes any business conducted by a registered credit services organization, a licensed check‐cashing business, a person engaged in the practice of debt adjusting, or a person who is involved in offering lease‐purchase agreements. -

To-Distribute Model and the Role of Banks in Financial Intermediation

Vitaly M. Bord and João A. C. Santos The Rise of the Originate- to-Distribute Model and the Role of Banks in Financial Intermediation 1.Introduction banks with yet another venue for distributing the loans that they originate. In principle, banks could create CLOs using the istorically, banks used deposits to fund loans that they loans they originated, but it appears they prefer to use collateral Hthen kept on their balance sheets until maturity. Over managers—usually investment management companies—that time, however, this model of banking started to change. Banks put together CLOs by acquiring loans, some at the time of began expanding their funding sources to include bond syndication and others in the secondary loan market.2 financing, commercial paper financing, and repurchase Banks’ increasing use of the originate-to-distribute model agreement (repo) funding. They also began to replace their has been critical to the growth of the syndicated loan market, traditional originate-to-hold model of lending with the so- of the secondary loan market, and of collateralized loan called originate-to-distribute model. Initially, banks limited obligations in the United States. The syndicated loan market the distribution model to mortgages, credit card credits, and rose from a mere $339 billion in 1988 to $2.2 trillion in 2007, car and student loans, but over time they started to apply it the year the market reached its peak. The secondary loan to corporate loans. This article documents how banks adopted market, in turn, evolved from a market in which banks the originate-to-distribute model in their corporate lending participated occasionally, most often by selling loans to other business and provides evidence of the effect that this shift has banks through individually negotiated deals, to an active, had on the growth of nonbank financial intermediation. -

Default Option Exercise Over the Financial Crisis and Beyond*

Review of Finance, 2021, 153–187 doi: 10.1093/rof/rfaa022 Advance Access Publication Date: 17 August 2020 Default Option Exercise over the Financial Crisis and beyond* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/25/1/153/5893492 by guest on 19 February 2021 Xudong An1, Yongheng Deng2, and Stuart A. Gabriel3 1Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2University of Wisconsin – Madison, and 3University of California, Los Angeles Anderson School of Management Abstract We document changes in borrowers’ sensitivity to negative equity and show height- ened borrower default propensity as a fundamental driver of crisis period mortgage defaults. Estimates of a time-varying coefficient competing risk hazard model reveal a marked run-up in the default option beta from 0.2 during 2003–06 to about 1.5 dur- ing 2012–13. Simulation of 2006 vintage loan performance shows that the marked upturn in the default option beta resulted in a doubling of mortgage default inci- dence. Panel data analysis indicates that much of the variation in default option ex- ercise is associated with the local business cycle and consumer distress. Results also indicate elevated default propensities in sand states and among borrowers seeking a crisis-period Home Affordable Modification Program loan modification. JEL classification: G21, G12, C13, G18 Keywords: Mortgage default, Option exercise, Default option beta, Time-varying coefficient hazard model Received August 19, 2017; accepted October 23, 2019 by Editor Amiyatosh Purnanandam. * We thank Sumit Agarwal, Yacine Ait-Sahalia, -

Your Step-By-Step Mortgage Guide

Your Step-by-Step Mortgage Guide From Application to Closing Table of Contents In this Guide, you will learn about one of the most important steps in the homebuying process — obtaining a mortgage. The materials in this Guide will take you from application to closing and they’ll even address the first months of homeownership to show you the kinds of things you need to do to keep your home. Knowing what to expect will give you the confidence you need to make the best decisions about your home purchase. 1. Overview of the Mortgage Process ...................................................................Page 1 2. Understanding the People and Their Services ...................................................Page 3 3. What You Should Know About Your Mortgage Loan Application .......................Page 5 4. Understanding Your Costs Through Estimates, Disclosures and More ...............Page 8 5. What You Should Know About Your Closing .....................................................Page 11 6. Owning and Keeping Your Home ......................................................................Page 13 7. Glossary of Mortgage Terms .............................................................................Page 15 Your Step-by-Step Mortgage Guide your financial readiness. Or you can contact a Freddie Mac 1. Overview of the Borrower Help Center or Network which are trusted non- profit intermediaries with HUD-certified counselors on staff Mortgage Process that offer prepurchase homebuyer education as well as financial literacy using tools such as the Freddie Mac CreditSmart® curriculum to help achieve successful and Taking the Right Steps sustainable homeownership. Visit http://myhome.fred- diemac.com/resources/borrowerhelpcenters.html for a to Buy Your New Home directory and more information on their services. Next, Buying a home is an exciting experience, but it can be talk to a loan officer to review your income and expenses, one of the most challenging if you don’t understand which can be used to determine the type and amount of the mortgage process. -

The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 159–181 The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed Robert L. Hetzel ilton Friedman (1982, 103) wrote: “In our book on U.S. mon- etary history, Anna Schwartz and I found it possible to use M one sentence to describe the central principle followed by the Federal Reserve System from the time it began operations in 1914 to 1952. That principle, to quote from our book, is: ‘Ifthe ‘money market’ is properly managed so as to avoid the unproductive use of credit and to assure the availability of credit for productive use, then the money stock will take care of itself.’” For Friedman, the reference to “the money stock”was synonymous with “the price level.”1 How did American monetary experience and debate in the 19th century give rise to these “real bills” views as a guide to Fed policy in the pre-World War II period? As distilled in the real bills doctrine, the founders of the Fed under- stood the Federal Reserve System as a decentralized system of reserve depositories that would allow the expansion and contraction of currency and credit based on discounting member-bank paper that originated out of productive activity. By discounting these “real bills,”the short- term loans that …nanced trade and goods in the process of production, policymakers ful…lled their responsibilities as they understood them. That is, they would provide the reserves required to accommodate the “legitimate,” nonspeculative, demands for credit.2 In so doing, they The author acknowledges helpful comments from Huberto Ennis, Motoo Haruta, Gary Richardson, Robert Sharp, Kurt Schuler, Ellis Tallman, and Alexander Wolman. -

Predatory Lending Questions and Answers

Attachment A Predatory Lending Questions and Answers 1) What is the difference between subprime lending and predatory lending? Subprime Lending The prime lending market offers loans to persons with excellent credit and employment history, and an income sufficient to support the loan amount. It generally offers borrowers many loan choices and the lowest mortgage rates. Prime lenders include banks, thrifts and credit unions that are subject to extensive oversight and regulation by federal and state governments. According to HUD, nine out of ten families take out prime loans when purchasing or refinancing their mortgages.1 Subprime lenders serve high-risk borrowers who would otherwise have difficulty obtaining a loan. Subprime loans usually have higher interest rates and fees than prime loans to compensate the lender for taking on higher repayment risk. Subprime lenders adjust their interest rates and fees according to the risk of the individual loan applicant and any additional loan origination costs. The subprime market is an important part of the financial system because it provides credit to consumers who would otherwise be unable to borrow money, and allows high-risk borrowers to repair their credit rating by paying back their new loan on schedule. Through home equity lines of credit and refinances, the subprime market can also provide consumers in difficult situations the ability to access part of their housing wealth to get them through bad financial periods. Predatory Lending Although there is no set definition for predatory lending, it is generally used to describe a set of practices through which a broker, lender or other participant takes unfair advantage of a borrower, often through deception, fraud or manipulation to make a loan that has terms that are a disadvantageous to the borrower. -

Household Debt and Credit

CENTER FOR MICROECONOMIC DATA WWW.NEWYORKFED.ORG/MICROECONOMICS QUARTERLY REPORT ON HOUSEHOLD DEBT AND CREDIT 2017:Q4 (RELEASED FEBRUARY 2018) FEDERAL RESERVE BANK of NEW YORK RESEARCH AND STATISTICS GROUP ANALYSIS BASED ON NEW YORK FED CONSUMER CREDIT PANEL/EQUIFAX DATA Household Debt and Credit Developments in 2017Q41 Aggregate household debt balances increased in the fourth quarter of 2017, for the 14th consecutive quarter, and are now $473 billion higher than the previous (2008Q3) peak of $12.68 trillion. As of December 31, 2017, total household indebtedness was $13.15 trillion, a $193 billion (1.5%) increase from the third quarter of 2017. Overall household debt is now 17.9% above the 2013Q2 trough. Mortgage balances, the largest component of household debt, increased substantially during the fourth quarter. Mortgage balances shown on consumer credit reports on December 31 stood at $8.88 trillion, an increase of $139 billion from the third quarter of 2017. Balances on home equity lines of credit (HELOC) declined again, by $4 billion and now stand at $444 billion. Non-housing balances, which have been increasing steadily for nearly 6 years overall, saw a $58 billion increase in the fourth quarter. Auto loans grew by $8 billion and credit card balances increased by $26 billion, while student loans saw a $21 billion increase. New extensions of credit declined slightly in the fourth quarter. Mortgage originations, which we measure as appearances of new mortgage balances on consumer credit reports and which include refinanced mortgages, were at $452 billion, down from $479 billion in the third quarter. There were $137 billion in auto loan originations in the fourth quarter of 2017, a small decline from 2017Q3 but making 2017 auto loan origination volume the highest year observed in our data.