Inside the Refugees' Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

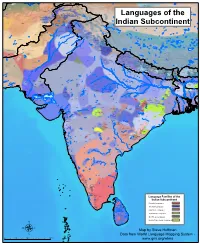

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Documenting Languages in Danger

11/19/2012 Documenting Languages in Danger “Languages are not only tools of communication; they also reflect a view of the world. Languages are vehicles of value systems and cultural expressions Inam Ullah and are an essential component of the living Chairperson, heritage of humanity. Yet, many of them are in Mother Tongue and Heritage danger of disappearing.” for Education and Research (MOTHER) UNESCO on Language Endangerment We will discuss about…. What is Language Endangerment? o What is Language Endangerment? o Languages of Pakistan o Factors of Language Endangerment o Why should we care? o What is Language Documentation? An endangered language is a language that is at o Some popular tools of documentation o Organizations involved in Language Documentation risk of falling out of use as its speakers die out o Efforts on International Level or shift to speaking another language. o Efforts on National Level o Efforts on Regional Level o Efforts on Community/Local Level o Process and Steps of Language Documentation o What Language Technology can do for saving Endangered Languages? o Computational Resources needed for Pakistani Languages o Related activities 1 11/19/2012 Language loss occurs when the language has no Languages are currently disappearing at an more native speakers, and becomes a " dead accelerated rate due to the processes of language ". If eventually no one speaks the globalization and neo-colonialism, where the language at all, it becomes an " extinct economically and politically powerful language ". languages dominate other languages. Number of languages is not precise The top 20 languages spoken by more than 50 No precise number of contemporary languages in the million speakers each are spoken by 50% of world is known, and it is not well defined what the world's population, whereas many of the constitutes a separate language rather than a dialect. -

An Acoustic Phonetic Study of Six Accents of Urdu in Pakistan

An Acoustic Phonetic Study of Six Accents of Urdu in Pakistan by Mahwish Farooq M. Phil in Applied Linguistics Department of English Language and Literature School of Social Sciences and Humanities University of Management and Technology 2014 An Acoustic Phonetic Study of Six Accents of Urdu in Pakistan by Mahwish Farooq M. Phil in Applied Linguistics This research was submitted to University of Management and Technology, Johar Town, Lahore in the partial fulfillment for the requirements of the Degree of M. Phil in Applied Linguistics Department of English Language and Literature School of Social Sciences and Humanities University of Management and Technology 2014 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Start with the name of Allah Almighty who holds and guides us in darkness. I owe to start with the praise of Allah Almighty as I know I am nothing without His help. It is my pleasure to acknowledge different people who have been contributed a lot to my thesis. Firstly, I am incredibly thankful to my supervisor Prof. Dr. Sarmad Hussain for inspiring me with the idea for this project and of course for supervising me. I am very lucky to have a supervisor like him. I would like to express my gratitude for his patience, encouragement and guidance during my research. He is an inspiration for me to enter into the challenging field of research. I am very obliged and thankful to him for responding my queries each and every time during this work. I am very grateful to the former chairperson Mr. Rao Jalil and the present chairperson Dr. Shaban of Department of English Language and Literature, for their co- operation and guidance. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Pashto, Southern Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Shughni Chinese, Mandarin Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Wakhi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Khowar Khowar Domaaki Khowar Kati Shina Farsi, Eastern Yidgha Munji Kati Kalasha Gujari Kati KatiPhalura Gujari Kalami Shina, Kohistani Gawar-BatiKamviri Kalami Dameli TorwaliKohistani, Indus Gujari Chilisso Pashayi, Northwest Prasuni Kamviri Balti Kati Ushojo Gowro Languages of the Gawar-Bati Waigali Savi Chilisso Ladakhi Ladakhi Bateri Pashayi, SouthwestAshkun Tregami Pashayi, Northeast Shina Purik Grangali Shina Brokskat ParyaPashayi, Southeast Aimaq Shumashti Hindko, Northern Hazaragi GujariKashmiri Pashto, Northern Purik Tirahi Ladakhi Changthang Kashmiri Gujari Indian Subcontinent Gujari Pahari-PotwariGujari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Hindko, Southern Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Ormuri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Dogri-Kangri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Pashto, Southern Ladakhi Pashto, Central Khams Pahari, Kullu Kinnauri, Bhoti KinnauriSunam Gahri Shumcho Panjabi, Western Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Kinnauri, Chitkuli Pahari, Mahasu Panjabi, Eastern Panang Jaunsari Garhwali Balochi, Western Pashto, Southern Khetrani Tehri Rawat Tibetan Hazaragi Waneci Rawat Brahui Saraiki DarmiyaByangsi Chaudangsi Tibetan Balochi, Western Chaudangsi Bagri Kumauni Humla Bhotia Rangkas Dehwari Mugu Kumauni Tichurong Dolpo Haryanvi Urdu Buksa Lopa Nepali Kaike Panchgaunle Balochi, Eastern Raute Tichurong Sholaga Baragaunle Raji Nar Phu Tharu, Rana Sonha Thakali Kham, GamaleKham, Sheshi -

Soomro, Niaz H. (2016) Towards an Understanding of Pakistani Undergraduates’ Current Attitudes Towards Learning and Speaking English

n Soomro, Niaz H. (2016) Towards an understanding of Pakistani undergraduates’ current attitudes towards learning and speaking English. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7730/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Towards an Understanding of Pakistani Undergraduates’ Current Attitudes towards Learning and Speaking English By Niaz H. Soomro, M.Ed. ELT Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Education College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow 2016 ii Abstract The English language has an important place in Pakistan and in its education system, not least because of the global status of English and its role in employment. Realising the need to enhance language learning outcomes, especially at the tertiary level, the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan has put in place some important measures to improve the quality of English language teaching practice through its English Language Teaching Reforms (ELTR) project. However, there is a complex linguistic, educational and ethnic diversity in Pakistan and that diversity, alongside the historical and current role of English in the country, makes any language teaching reform particularly challenging. -

WILDRE-2 2Nd Workshop on Indian Language Data

WILDRE2 - 2nd Workshop on Indian Language Data: Resources and Evaluation Workshop Programme 27th May 2014 14.00 – 15.15 hrs: Inaugural session 14.00 – 14.10 hrs – Welcome by Workshop Chairs 14.10 – 14.30 hrs – Inaugural Address by Mrs. Swarn Lata, Head, TDIL, Dept of IT, Govt of India 14.30 – 15.15 hrs – Keynote Lecture by Prof. Dr. Dafydd Gibbon, Universität Bielefeld, Germany 15.15 – 16.00 hrs – Paper Session I Chairperson: Zygmunt Vetulani Sobha Lalitha Devi, Vijay Sundar Ram and Pattabhi RK Rao, Anaphora Resolution System for Indian Languages Sobha Lalitha Devi, Sindhuja Gopalan and Lakshmi S, Automatic Identification of Discourse Relations in Indian Languages Srishti Singh and Esha Banerjee, Annotating Bhojpuri Corpus using BIS Scheme 16.00 – 16.30 hrs – Coffee break + Poster Session Chairperson: Kalika Bali Niladri Sekhar Dash, Developing Some Interactive Tools for Web-Based Access of the Digital Bengali Prose Text Corpus Krishna Maya Manger, Divergences in Machine Translation with reference to the Hindi and Nepali language pair András Kornai and Pushpak Bhattacharyya, Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization Niladri Sekhar Dash, Generation of a Digital Dialect Corpus (DDC): Some Empirical Observations and Theoretical Postulations S Rajendran and Arulmozi Selvaraj, Augmenting Dravidian WordNet with Context Menaka Sankarlingam, Malarkodi C S and Sobha Lalitha Devi, A Deep Study on Causal Relations and its Automatic Identification in Tamil Panchanan Mohanty, Ramesh C. Malik & Bhimasena Bhol, Issues in the Creation of Synsets in Odia: A Report1 Uwe Quasthoff, Ritwik Mitra, Sunny Mitra, Thomas Eckart, Dirk Goldhahn, Pawan Goyal, Animesh Mukherjee, Large Web Corpora of High Quality for Indian Languages i Massimo Moneglia, Susan W. -

The Concept of Language Is As Old As the Human Itself. According to The

Grassroots Vol. 49, No.I January-June 2015 LANGUAGE AND DIALECT: CRITERIA AND HISTORICAL EVIDENCE María Isabel Maldonado García Akhtar Hussain Sandhu ABSTRACT History is replete with events, change, cause and effect on the basis of language. Political movements and geographical changes occurred in different corners of the world and eras have slightly and massively been linked with language. Many regions are currently facing separatist movements mainly rooted in languages or dialects. A few authors have written about the criteria for defining a particular linguistic system as a language in terms of the number of speakers, its prestige, whether they have been accepted as national languages, whether they present written forms and literary traditions, whether similar linguistic systems exist in the same country or area which present an elevated level of lexical similarity, whether they have less number of speakers, etc. It seems simple to differentiate between a language and a dialect. However, although the definition of language seems to be clear and every dictionary of the world contains it, in practical terms when facing the dilemma of whether a particular linguistic system is a language or a dialect, these definitions are blurry from a scientific point of view and sociolinguistic and political pressures may play a role in many cases. This paper will propose better criteria towards differentiation of language and dialect basing the argument on the empirical evidence of the history of linguistics. _________________________ Keywords: Language, dialect, Sindhi, Bengali, Punjabi, Saraiki, language varieties, difference between language and dialect. DEFINITIONS OF LANGUAGE AND DIALECT The concept of language is as old as the human itself. -

The Vowel Systems of Five Iranian Balochi Dialects

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Linguistica Upsaliensia 13 and Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 20 The Vowel Systems of Five Iranian Balochi Dialects Farideh Okati Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in 6-0031, Engelska Parken, Thunbergsvägen 3, Uppsala, Wednesday, December 12, 2012 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Okati, F. 2012. The Vowel Systems of Five Iranian Balochi Dialects. Studia Linguistica Upsaliensia 13. Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 20. 241 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-8536-8. ISBN 978-91-554-8534-4. The vowel systems of five selected Iranian Balochi dialects are investigated in this study, which is the first work to apply empirical acoustic analysis to a large body of recorded data on the vowel inventories of different Balochi dialects spoken in Iran. The selected dialects are spoken in the five regions of Sistan (SI), Saravan (SA), Khash (KH), Iranshahr (IR), and Chabahar (CH) located in the province Sistan and Baluchestan in the southeast of Iran. The aim of the present fieldwork- based survey is to study how similar the vowel systems of these dialects are to the Common Ba- lochi vowel system (i, iː, u, uː, a, aː, eː, oː), which is represented as the vowel inventory for the Balochi dialects in general, as well as how similar these dialects are to one another. The investigation shows that length is contrastive in these dialects, although the durational dif- ferences between the long and short counterparts are quite small in some dialects. The study also reveals that there are some differences between the vowel systems of these dialects and the Com- mon Balochi sound inventory. -

Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization

Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization Andras´ Kornai, Pushpak Bhattacharyya Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Department of Algebra Indian Institute of Technology, Budapest Institute of Technology [email protected], [email protected] Abstract We describe the planned Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization (ISLV) project, which aims at turning as many languages and dialects of the subcontinent into digitally viable languages as feasible. Keywords: digital vitality, language vitalization, Indian subcontinent In this position paper we describe the planned Indian Sub- gesting that efforts aimed at building language technology continent Language Vitalization (ISLV) project. In Sec- (see Section 4) are best concentrated on the less vital (but tion 1 we provide the rationale why such a project is called still vital or at the very least borderline) cases at the ex- for and some background on the language situation on the pense of the obviously moribund ones. To find this border- subcontinent. Sections 2-5 describe the main phases of the line we need to distinguish the heritage class of languages, planned project: Survey, Triage, Build, and Apply, offering typically understood only by priests and scholars, from the some preliminary estimates of the difficulties at each phase. still class, which is understood by native speakers from all walks of life. For heritage language like Sanskrit consider- 1. Background able digital resources already exist, both in terms of online The linguistic diversity of the Indian Subcontinent is available material (in translations as well as in the origi- remarkable, and in what follows we include here not nal) and in terms of lexicographical and grammatical re- just the Indo-Aryan family, but all other families like sources of which we single out the Koln¨ Sanskrit Lexicon Dravidian and individual languages spoken in the broad at http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/monier and the geographic area, ranging from Kannada and Telugu INRIA Sanskrit Heritage site at http://sanskrit.inria.fr. -

Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 Code for Comprehensive Coverage of Languages

© ISO 2003 — All rights reserved ISO TC 37/SC 2 N 292 Date: 2003-08-29 ISO/CD 639-3 ISO TC 37/SC 2/WG 1 Secretariat: ON Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages Codes pour la représentation de noms de langues ― Partie 3: Code alpha-3 pour un traitement exhaustif des langues Warning This document is not an ISO International Standard. It is distributed for review and comment. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an International Standard. Recipients of this draft are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting documentation. Document type: International Standard Document subtype: Document stage: (30) Committee Stage Document language: E C:\Documents and Settings\여동희\My Documents\작업파일\ISO\Korea_ISO_TC37\심의문서\심의중문서\SC2\N292_TC37_SC2_639-3 CD1 (E) (2003-08-29).doc STD Version 2.1 ISO/CD 639-3 Copyright notice This ISO document is a working draft or committee draft and is copyright-protected by ISO. While the reproduction of working drafts or committee drafts in any form for use by participants in the ISO standards development process is permitted without prior permission from ISO, neither this document nor any extract from it may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form for any other purpose without prior written permission from ISO. Requests for permission to reproduce this document for the purpose of selling it should be addressed as shown below or to ISO's member body in the country of the requester: [Indicate the full address, telephone number, fax number, telex number, and electronic mail address, as appropriate, of the Copyright Manger of the ISO member body responsible for the secretariat of the TC or SC within the framework of which the working document has been prepared.] Reproduction for sales purposes may be subject to royalty payments or a licensing agreement.