Language Policy, Multilingualism and Language Vitality in Pakistan1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(And Potential) Language and Linguistic Resources on South Asian Languages

CoRSAL Symposium, University of North Texas, November 17, 2017 Existing (and Potential) Language and Linguistic Resources on South Asian Languages Elena Bashir, The University of Chicago Resources or published lists outside of South Asia Digital Dictionaries of South Asia in Digital South Asia Library (dsal), at the University of Chicago. http://dsal.uchicago.edu/dictionaries/ . Some, mostly older, not under copyright dictionaries. No corpora. Digital Media Archive at University of Chicago https://dma.uchicago.edu/about/about-digital-media-archive Hock & Bashir (eds.) 2016 appendix. Lists 9 electronic corpora, 6 of which are on Sanskrit. The 3 non-Sanskrit entries are: (1) the EMILLE corpus, (2) the Nepali national corpus, and (3) the LDC-IL — Linguistic Data Consortium for Indian Languages Focus on Pakistan Urdu Most work has been done on Urdu, prioritized at government institutions like the Center for Language Engineering at the University of Engineering and Technology in Lahore (CLE). Text corpora: http://cle.org.pk/clestore/index.htm (largest is a 1 million word Urdu corpus from the Urdu Digest. Work on Essential Urdu Linguistic Resources: http://www.cle.org.pk/eulr/ Tagset for Urdu corpus: http://cle.org.pk/Publication/papers/2014/The%20CLE%20Urdu%20POS%20Tagset.pdf Urdu OCR: http://cle.org.pk/clestore/urduocr.htm Sindhi Sindhi is the medium of education in some schools in Sindh Has more institutional backing and consequent research than other languages, especially Panjabi. Sindhi-English dictionary developed jointly by Jennifer Cole at the University of Illinois Urbana- Champaign and Sarmad Hussain at CLE (http://182.180.102.251:8081/sed1/homepage.aspx). -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

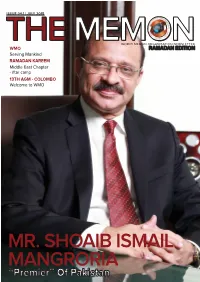

MR. SHOAIB ISMAIL MANGRORIA “Premier” of Pakistan the MEMON | ISSUE 04.1 INTRODUCTION

ISSUE 04.1 | JULY 2015 THETHE MEMONMEMONWORLD MEMON ORGANISATION NEWSLETTER WMO RAMADAN EDITION Serving Mankind RAMADAN KAREEM Middle East Chapter - iftar camp 13TH AGM - COLOMBO Welcome to WMO MR. SHOAIB ISMAIL MANGRORIA “Premier” Of Pakistan THE MEMON | ISSUE 04.1 INTRODUCTION THETHE MEMONMEMON INTRODUCTION World Memon Organisation - Serving Mankind I stood undaunted during the Gujarat I am getting together a group of young- riots and rehabilitated my aicted sters in the Big Apple to do community brothers and sisters. I walked in neck work. I organise events to promote deep waters to build homes for flood brotherhood and sports every month in victims in Sindh. I drove to shelters in Dubai. I ran the Mumbai marathon to Durban with medical supplies to treat fund a worthy cause. the injured in the Xenophobic attacks. I am the youth wing of WMO. I am a member of WMO. We are the future of Mankind. We uplift mankind I was knighted by the Queen of I build homes. I educate children. I England for my extensive charitable provide a brighter future and make this work. I was awarded the “Presidential world a better place. Order of Meritorious Service” by the President of the Republic of Botswana I donate to WMO. for my exceptional generosity and We uphold Mankind. philanthropy. I was honoured by the Premier of Pakistan for my dedication I sent blankets to shivering children in and passion towards community work. the winter of war torn Syria. I collected funds for relief packages to be delivered I am WMO. in flood ravaged Malawi. -

Languages of Kohistan. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 1 LANGUAGES OF KOHISTAN Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Calvin R. Rensch Sandra J. Decker Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2002 ISBN 969-8023-11-9 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................viii Maps................................................................................................................. -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

The Pamir Languages

DEMO : Purchase from www.A-PDF.com to remove the watermark CHAPTER FOURTEEN A THE PAMIR LANGUAGES D. (Joy) I Edelman and Leila R. Dodykhudoeva 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Overview "Pamir languages" is the generalized conventional term fo r a group of languages that belong to the eastern branch of the Iranian language fa mily, and are spoken in the valleys of the western and southern Pamirs and adjacent regions: the Mountainous Badakhshan Autonomous Region (Tajik Viloya ti Ku histoni Badakhshon) of the Republic Tajikistan; the Badakhshan province in Afghanistan; parts of northern Pakistan (Chitral, Gilgit, Hunza); and parts of the Xinjiang-Uygur Autonomous Region of China. The Pamir languages constitute fo ur distinct genetic sub-groups that derive from several distinct proto-dialects of East Iranian origin (see also Chapters 14b and 15 on Shughn(an)i and Wakhi): I. "North Pamir" group (a) Old Wanji (extinct), relatively close to (b) Yazghulami, and (c) the Shughni Rushani group to the south of it (see Chapter 14b). 2. Ishkashimi group (a) Ishkashimi proper, (b) Sanglichi, (c) Zebaki (extinct). 3. Wa khi. 4. Also, owing to a series of features (a) Munji, (b) Yidgha. Extinct Sarghulami in Afghan Badakhshan is usually included. However, the very existence of this particular vernacular is doubtful. The material, described by Prof. I. I. Zarubin in the 1920s, could never be verified. It is based on the information from a speaker of one of the neighboring villages of Sarghulam, who called it la vz-i mazor 'the speech of mazar', presumably referring to the Afghan village of Sarghulam, which had such a shrine. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Classification of Eastern Iranian Languages

62 / 2014 Ľubomír Novák 1 QUESTION OF (RE)CLASSIFICATION OF EASTERN IRANIAN LANGUAGES STATI – ARTICLES – AUFSÄTZE – СТАТЬИ AUFSÄTZE – ARTICLES – STATI Abstract The Eastern Iranian languages are traditionally divided into two subgroups: the South and the North Eastern Iranian languages. An important factor for the determination of the North Eastern and the South Eastern Iranian groups is the presence of isoglosses that appeared already in the Old Iranian period. According to an analysis of isoglosses that were used to distinguish the two branches, it appears that most likely there are only two certain isoglosses that can be used for the division of the Eastern Iranian languages into the two branches. Instead of the North-South division of the Eastern Iranian languages, it seems instead that there were approximately four dialect nuclei forming mi- nor groups within the Eastern Iranian branch. Furthermore, there are some languages that geneti- cally do not belong to these nuclei. In the New Iranian period, several features may be observed that link some of the languages together, but such links often have nothing in common with a so-called genetic relationship. The most interesting issue is the position of the so-called Pamir languages with- in the Eastern Iranian group. It appears that not all the Pamir languages are genetically related; their mutual proximity, therefore, may be more sufficiently explained by later contact phenomena. Keywords Eastern Iranian languages; Pamir languages; language classification; linguistic genealogy. The Iranian languages are commonly divided into two main groups: the Eastern and Western Iranian languages. Each of the groups is subsequently divided in two other subgroups – the Northern and Southern1. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Manual of Instructions for Editing, Coding and Record Management of Individual Slips

For offiCial use only CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 MANUAL OF INSTRUCTIONS FOR EDITING, CODING AND RECORD MANAGEMENT OF INDIVIDUAL SLIPS PART-I MASTER COPY-I OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL&. CENSUS COMMISSIONER. INOI.A MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS Pages GENERAlINSTRUCnONS 1-2 1. Abbreviations used for urban units 3 2. Record Management instructions for Individual Slips 4-5 3. Need for location code for computer processing scheme 6-12 4. Manual edit of Individual Slip 13-20 5. Code structure of Individual Slip 21-34 Appendix-A Code list of States/Union Territories 8a Districts 35-41 Appendix-I-Alphabetical list of languages 43-64 Appendix-II-Code list of religions 66-70 Appendix-Ill-Code list of Schedules Castes/Scheduled Tribes 71 Appendix-IV-Code list of foreign countries 73-75 Appendix-V-Proforma for list of unclassified languages 77 Appendix-VI-Proforma for list of unclassified religions 78 Appendix-VII-Educational levels and their tentative equivalents. 79-94 Appendix-VIII-Proforma for Central Record Register 95 Appendix-IX-Profor.ma for Inventory 96 Appendix-X-Specimen of Individual SHp 97-98 Appendix-XI-Statement showing number of Diatricts/Tehsils/Towns/Cities/ 99 U.AB.lC.D. Blocks in each State/U.T. GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS This manual contains instructions for editing, coding and record management of Individual Slips upto the stage of entry of these documents In the Direct Data Entry System. For the sake of convenient handling of this manual, it has been divided into two parts. Part·1 contains Management Instructions for handling records, brief description of thf' process adopted for assigning location code, the code structure which explains the details of codes which are to be assigned for various entries in the Individual Slip and the edit instructions. -

Inside the Refugees' Crisis

Research Centre on Identity and Migration Issues University of Oradea RCIMI Journal of Identity and Migration Studies University of Oradea Publishing House Volume 10, number 2, November 2016 JOURNAL OF IDENTITY AND MIGRATION STUDIES The Journal of Identity and Migration Studies (JIMS) is an online open-access review published semi- annually under the auspices of the Research Centre on Identity and Migration Issues – RCIMI, from the Department of Political Science and Communication Sciences, University of Oradea, Romania. Director Lia Pop, University of Oradea, Romania Editor-In-Chief Cristina Matiuta, University of Oradea, Romania Deputy Editor-In-Chief Marius I. Tatar, University of Oradea, Romania Editorial Board Gabriel Badescu, Babes-Bolyai University, Romania Bernardo Cardinale, University of Teramo, Italy Radu Cinpoes, Kingston University, London, UK Vasile Cucerescu, Institute of International Relations, Chisinau Ioan Horga, University of Oradea, Romania Alexandru Ilies, University of Oradea, Romania Zaiga Krisjane, University of Latvia, Latvia Jan Wendt, University of Gdansk, Poland Luca Zarrilli, University of Chieti-Pescara, Italy Assistant Editors Ioana Albu, University of Oradea, Romania Dan Apateanu, University of Oradea, Romania Alina Brihan, University of Oradea, Romania Gabriela Gaudenhooft, University of Oradea, Romania Ioan Laza, University of Oradea, Romania Irina Pop, University of Oradea, Romania The responsibility for the content of the contributions published in JIMS belongs exclusively to the authors. The views expressed in the articles and other contributions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors of JIMS. JIMS - JOURNAL OF IDENTITY AND MIGRATION STUDIES Research Centre on Identity and Migration Issues - RCIMI Department of Political Science and Communication Science University of Oradea Address: Str.