Uncovering China's Influence in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Deal – the Coordinators

Green Deal – The Coordinators David Sassoli S&D ”I want the European Green Deal to become Europe’s hallmark. At the heart of it is our commitment to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent. It is also a long-term economic imperative: those who act first European Parliament and fastest will be the ones who grasp the opportunities from the ecological transition. I want Europe to be 1 February 2020 – H1 2024 the front-runner. I want Europe to be the exporter of knowledge, technologies and best practice.” — Ursula von der Leyen Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle President of the European Commission Head of Cabinet Secretary General Chairs and Vice-Chairs Political Group Coordinators EPP S&D EPP S&D Renew ID Europe ENVI Renew Committee on Europe Dan-Ştefan Motreanu César Luena Peter Liese Jytte Guteland Nils Torvalds Silvia Sardone Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator the Environment, Public Health Greens/EFA GUE/NGL Greens/EFA ECR GUE/NGL and Food Safety Pacal Canfin Chair Bas Eickhout Anja Hazekamp Bas Eickhout Alexandr Vondra Silvia Modig Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator S&D S&D EPP S&D Renew ID Europe EPP ITRE Patrizia Toia Lina Gálvez Muñoz Christian Ehler Dan Nica Martina Dlabajová Paolo Borchia Committee on Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Industry, Research Renew ECR Greens/EFA ECR GUE/NGL and Energy Cristian Bușoi Europe Chair Morten Petersen Zdzisław Krasnodębski Ville Niinistö Zdzisław Krasnodębski Marisa Matias Vice-Chair Vice-Chair -

Runmed March 2001 Bulletin

No. 325 MARCH Bulletin 2001 RUNNYMEDE’S QUARTERLY Challenge and Change Since the release of our Commission’s report, The Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain, Runnymede has been living in interesting times. Substantial and ongoing media coverage – from the enlivening to the repellent – has fueled the debate.Though the press has focused on some issues at the expense of others, numerous events organised to broaden the discussion continue to explore the Report’s substantial content, and international interest has been awakened. At such a moment, it is a great external organisations wishing to on cultural diversity in the honour for me to be taking over the arrange events. workplace, Moving on up? Racial Michelynn Directorship of Runnymede.The 3. A National Conference to Equality and the Corporate Agenda, a Laflèche, Director of the challenges for the next three years mark the first anniversary of the Study of FTSE-100 Companies,in Runnymede Trust are a stimulus for me and our Report’s launch is being arranged for collaboration with Schneider~Ross. exceptional team, and I am facing the final quarter of 2001, in which This publication continues to be in them with enthusiasm and optimism. we will review the responses to the high demand and follow-up work to Runnymede’s work programme Report over its first year. A new that programme is now in already reflects the key issues and element will be introduced at this development for launching in 2001. recommendations raised in the stage – how to move the debate Another key programme for Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain Report, beyond the United Kingdom to the Runnymede is our coverage of for which a full dissemination level of the European Union. -

Working with Vietnam, Russia's Rosneft Draws China's

Working with Vietnam, Russia's Rosneft Draws China’s Ire Rosneft is a crucial arm of Russian foreign policy, yet functions at times without direct Kremlin involvement. By Nicholas Trickett May 19, 2018 China has been the driving force behind Russia’s “Pivot to Asia,” becoming the largest individual consumer of Russian Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, and Vietnamese oil among its energy trade partners. Early this month, it President Tran Dai Quang attend a news conference was reported that Russia had completed the delivery of its following their meeting in the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia first S-400 regiment – the country’s most advanced air Thursday, June 29, 2017. defense system for export – to China. Beijing’s Ministry of Image Credit: Natalia Kolesnikova/Pool Photo via AP Commerce is signaling that trade turnover with Russia may reach $100 billion this year Russia and that investment under the aegis of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is growing fastest in percentage terms in Russia. Trade is up because oil prices are up, not necessarily because of an economic breakthrough, but the messaging is part of a broader commitment to making it appear as though all is well between the two countries. Two recent developments mark a significant change in the relationship. First, CEFC China Energy walked away from a deal to acquire 14.16 percent of Rosneft’s shares. Mired in scandal, the company has come under heavy scrutiny about its international expansion at home. Qatar stepped in to buy the shares instead as Rosneft changed its corporate strategy to provide better returns for shareholders and entice Qatar. -

Energy China Forum 2019 9Th Asia-Pacific Shale Gas & Oil Summit 25-27 September, 2019 | Shanghai China

Energy China Forum 2019 9th Asia-Pacific Shale Gas & Oil Summit 25-27 September, 2019 | Shanghai China Opportunities in China Shale Gas & Oil OPPORTUNITY IN CHINA SHALE GAS & Oil MARKET As a fast growing market, China shale gas & oil industry has been proved with great resource potential, high government support and increasing drilling and fracturing operations, which makes the market full of opportunities for global technology, equipment and service providers. • Abundant shale resources: China is currently the 3rd largest shale gas producer in the world with a top reserve of 30 tcm. Meanwhile, China has nearly 100 billion tons of shale oil(tight oil) resources. • Highly valued and supported by the government: The country requires vigorous enhancement of domestic oil and gas development and formulate various supportive policies for shale development. • Surging production – It is the two most critical years of 2019-2020 for China to achieve its ambitious 5 years shale gas production target of 30 bcm. • Increasing capital investment: Both CNPC and Sinopec are increasing investment and expenditure with total expenditure for E&P of 216.1 billion CNY in 2018, up by 12% yoy. They are expected to stay high investment in 2019-2020 despite the market fluctuation. • Increasing operations - Starting from 2018, CNPC and Sinopec were accelerating their shale gas production. CNPC plans to drill 6,300 shale gas wells in total during 2018-2035. Sinopec plans to drill around 700 shale gas production wells during 2019-2020. • Cost/efficiency orientation – Chinese shale players are more eager than ever looking for cost-reducing and efficiency-optimizing solutions. -

China As a Hybrid Influencer: Non-State Actors As State Proxies COI HYBRID INFLUENCE COI

Hybrid CoE Research Report 1 JUNE 2021 China as a hybrid influencer: Non-state actors as state proxies COI HYBRID INFLUENCE COI JUKKA AUKIA Hybrid CoE Hybrid CoE Research Report 1 China as a hybrid influencer: Non-state actors as state proxies JUKKA AUKIA 3 Hybrid CoE Research Reports are thorough, in-depth studies providing a deep understanding of hybrid threats and phenomena relating to them. Research Reports build on an original idea and follow academic research report standards, presenting new research findings. They provide either policy-relevant recommendations or practical conclusions. COI Hybrid Influence looks at how state and non-state actors conduct influence activities targeted at Participating States and institutions, as part of a hybrid campaign, and how hostile state actors use their influence tools in ways that attempt to sow instability, or curtail the sovereignty of other nations and the independence of institutions. The focus is on the behaviours, activities, and tools that a hostile actor can use. The goal is to equip practitioners with the tools they need to respond to and deter hybrid threats. COI HI is led by the UK. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats tel. +358 400 253 800 www.hybridcoe.fi ISBN (web) 978-952-7282-78-6 ISBN (print) 978-952-7282-79-3 ISSN 2737-0860 June 2021 Hybrid CoE is an international hub for practitioners and experts, building Participating States’ and institutions’ capabilities and enhancing EU-NATO cooperation in countering hybrid threats, located in Helsinki, Finland. The responsibility for the views expressed ultimately rests with the authors. -

EU-Parlament: Ausschussvorsitzende Und Deren Stellvertreter*Innen Auf Den Konstituierenden Sitzungen Am Mittwoch, 10

EU-Parlament: Ausschussvorsitzende und deren Stellvertreter*innen Auf den konstituierenden Sitzungen am Mittwoch, 10. Juli 2019, haben die siebenundzwanzig permanenten Ausschüsse des EU-Parlaments ihre Vorsitzenden und Stellvertreter*innen gewählt. Nachfolgend die Ergebnisse (Reihenfolge analog zur Auflistung auf den Seiten des Europäischen Parlaments): Ausschuss Vorsitzender Stellvertreter Witold Jan WASZCZYKOEDKI (ECR, PL) AFET Urmas PAET (Renew, EE) David McALLISTER (EPP, DE) Auswärtige Angelegenheiten Sergei STANISHEV (S&D, BG) Željana ZOVKO (EPP, HR) Bernard GUETTA (Renew, FR) DROI Hannah NEUMANN (Greens/EFA, DE) Marie ARENA (S&D, BE) Menschenrechte Christian SAGARTZ (EPP, AT) Raphael GLUCKSMANN (S&D, FR) Nikos ANDROULAKIS (S&D, EL) SEDE Kinga GÁL (EPP, HU) Nathalie LOISEAU (RE, FR) Sicherheit und Verteidigung Özlem DEMIREL (GUE/NGL, DE) Lukas MANDL (EPP, AT) Pierrette HERZBERGER-FOFANA (Greens/EFA, DE) DEVE Norbert NEUSER (S&D, DE) Tomas TOBÉ (EPP, SE) Entwicklung Chrysoula ZACHAROPOULOU (RE, FR) Erik MARQUARDT (Greens/EFA, DE) Seite 1 14.01.2021 Jan ZAHRADIL (ECR, CZ) INTA Iuliu WINKLER (EPP, RO) Bernd LANGE (S&D, DE) Internationaler Handel Anna-Michelle ASIMAKOPOULOU (EPP, EL) Marie-Pierre VEDRENNE (RE, FR) Janusz LEWANDOWSKI (EPP, PL) BUDG Oliver CHASTEL (RE, BE) Johan VAN OVERTVELDT (ECR, BE) Haushalt Margarida MARQUES (S&D, PT) Niclas HERBST (EPP, DE) Isabel GARCÍA MUÑOZ (S&D, ES) CONT Caterina CHINNICI (S&D, IT) Monika HOHLMEIER (EPP, DE) Haushaltskontrolle Martina DLABAJOVÁ (RE, CZ) Tamás DEUTSCH (EPP, HU) Luděk NIEDERMAYER -

PPF Financial Holdings B.V. – Annual Accounts 2019

PPF Financial Holdings B.V. Annual accounts 2019 Content: Board of Directors report Annual accounts 2019 Consolidated financial statements Separate financial statements Other information Independent auditor’s report 1 Directors’ Report Description of the Company PPF Financial Holdings B.V. Date of deed on incorporation: 13.11.2014 Seat: Netherlands, Strawinskylaan 933, 1077XX Amsterdam Telephone: +31 (0) 208 812 120 Place of registration: Netherlands, Amsterdam Register (registration authority): Commercial Register of Netherlands Chamber of Commerce Registration number: 61880353 LEI: 31570014BNQ1Q99CNQ35 Authorised capital: EUR 45,000 Issued capital: EUR 45,000 Paid up capital: EUR 45,000 Principal business: Holding company activities and financing thereof Management Board of PPF Financial Holdings B.V. (the “Company”), is pleased to present to you the Directors’ report as part of the financial statements for the year 2019. This Directors’ report aims to provide a comprehensive overview of significant events within the Company as well as within the group of companies with which it forms a group. Board of Directors (the “Management Board”) Jan Cornelis Jansen, Director Rudolf Bosveld, Director Paulus Aloysius de Reijke, Director Lubomír Král, Director Kateřina Jirásková, Director General information The Company is the parent holding company of the group of companies (the “Group”) that operates in the field of financial services. The Group is composed of four main investments: Home Credit Group B.V., PPF banka a.s., Mobi Banka a.d. Beograd and ClearBank Ltd. The Company is a 100% subsidiary of PPF Group N.V. (together with its subsidiaries “PPF Group”). Except for the role of holding entity the Company generates significant interest income from intercompany and external loans. -

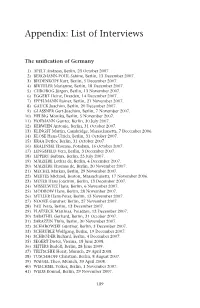

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

Asia's Energy Security

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #68 | november 2017 asia’s energy security and China’s Belt and Road Initiative By Erica Downs, Mikkal E. Herberg, Michael Kugelman, Christopher Len, and Kaho Yu cover 2 NBR Board of Directors Charles W. Brady Ryo Kubota Matt Salmon (Chairman) Chairman, President, and CEO Vice President of Government Affairs Chairman Emeritus Acucela Inc. Arizona State University Invesco LLC Quentin W. Kuhrau Gordon Smith John V. Rindlaub Chief Executive Officer Chief Operating Officer (Vice Chairman and Treasurer) Unico Properties LLC Exact Staff, Inc. President, Asia Pacific Wells Fargo Regina Mayor Scott Stoll Principal, Global Sector Head and U.S. Partner George Davidson National Sector Leader of Energy and Ernst & Young LLP (Vice Chairman) Natural Resources Vice Chairman, M&A, Asia-Pacific KPMG LLP David K.Y. Tang HSBC Holdings plc (Ret.) Managing Partner, Asia Melody Meyer K&L Gates LLP George F. Russell Jr. President (Chairman Emeritus) Melody Meyer Energy LLC Chairman Emeritus Honorary Directors Russell Investments Joseph M. Naylor Vice President of Policy, Government Lawrence W. Clarkson Dennis Blair and Public Affairs Senior Vice President Chairman Chevron Corporation The Boeing Company (Ret.) Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA U.S. Navy (Ret.) C. Michael Petters Thomas E. Fisher President and Chief Executive Officer Senior Vice President Maria Livanos Cattaui Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc. Unocal Corporation (Ret.) Secretary General (Ret.) International Chamber of Commerce Kenneth B. Pyle Joachim Kempin Professor; Founding President Senior Vice President Norman D. Dicks University of Washington; NBR Microsoft Corporation (Ret.) Senior Policy Advisor Van Ness Feldman LLP Jonathan Roberts Clark S. -

The Czech Foreign Policy in the Asia Pacific

CHAPTER 11 Chapter 11 The Czech Foreign Policy in the Asia Pacific IMPROVING BALANCE, MOSTLY UNFULFILLED POTENTIAL Rudolf Fürst, Alica Kizeková, David Kožíšek Executive Summary: The Czech relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC, hereinafter referred to as China) have again generated more interest than ties with other Asian nations in the Asia Pacific in 2017. A disagreement on the Czech-China agenda dominated the political and media debate, while more so- phisticated discussions about the engagement with China were still missing. In contrast, the bilateral relations with the Republic of Korea (ROK) and Japan did not represent a polarising topic in the Czech public discourse and thus remained largely unpoliticised due to the lack of interest and indifference of the public re- garding these relations. Otherwise, the Czech policies with other Asian states in selected regions revealed balanced attitudes with both proactive and reactive agendas in negotiating free trade agreements, or further promoting good relations and co-operation in trade, culture, health, environment, science, academia, tour- ism, human rights and/or defence. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT In 2017, the Czech foreign policy towards the Asia Pacific1 derived from the Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Czech Republic,2 which referred to the region as signifi- cant due to the economic opportunities it offered. It also stated that it was one of the key regions of the world due to its increased economic, political and security-related importance. Apart from the listed priority countries – China, Japan, and South Korea, as well as India – the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the re- gion of Central Asia are also mentioned as noteworthy in this government document. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2020

Taking action Annual Report and Financial Statements 2020 We make a difference in our customers’ lives by providing access to affordable credit in a respectful, responsible and straightforward way. We play an important role in society serving our home credit and digital products to 1.7 million customers who might otherwise be financially excluded. Resilient performance delivered in challenging times Customers (‘000) Credit issued (£m) Revenue (£m) 1,682 £772.2m £661.3m 889.1 2,521 866.4 1,360.6 1,353.0 825.8 1,301.5 2,301 2,290 756.8 2,109 1,145.0 661.3 1,682 772.2 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Pre-exceptional profit/ Profit/(loss) before tax Earnings/(loss) per share (loss) before tax (£m) (£m) (p) (£28.8m) (£40.7m) (28.9p) 114.0 114.0 109.3 109.3 105.6 105.6 96.0 96.0 33.8 32.2 33.7* 32.2 20.2 (28.8) (40.7) (28.9) 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 * 2017 pre-exceptional EPS Alternative Performance Measures This Annual Report and Financial Statements provides alternative performance measures (APMs) which are not defined or specified under the requirements of International Financial Reporting Standards. We believe these APMs provide readers with important additional information on our business. To support this, we have included an accounting policy note on APMs on page 115, a reconciliation of the APMs we use where relevant and a glossary on pages 154 to 155 indicating the APMs that we use, an explanation of how they are calculated and why we use them. -

Home Credit Slovakia, A.S

Home Credit Slovakia, a.s. Financial Statements for the year ended 31 December 2016 Translated from the Slovak original Home Credit Slovakia, a.s. Financial Statements for the year ended 31 December 2016 Contents Independent Auditor’s Report 3 Statement of Financial Position 6 Statement of Comprehensive Income 7 Statement of Changes in Equity 8 Statement of Cash Flows 9 Notes to the Financial Statements 10 - 2 - Home Credit Slovakia, a.s. Statement of Comprehensive Income for the year ended 31 December 2016 2016 2015 Note TEUR TEUR Interest income 14 12,286 9,309 Interest expense 14 (1,177) (1,072) Net interest income 11,109 8,237 Fee and commission income 15 4,933 5,501 Fee and commission expense 16 (6,932) (6,966) Net fee and commission expense (1,999) (1,465) Other operating income 17 10,159 20,697 Operating income 19,269 27,469 Impairment losses 18 (4,139) (3,550) General administrative expenses 19 (16,764) (17,144) Operating expenses (20,903) (20,694) Profit before tax (1,634) 6,775 Income tax expense 20 (256) (2,129) Net (loss)/profit for the year (1,890) 4,646 Total comprehensive income for the year (1,890) 4,646 - 7 - Home Credit Slovakia, a.s. Statement of Changes in Equity for the year ended 31 December 2016 Statutory Share Share reserve Retained capital premium fund earnings Total TEUR TEUR TEUR TEUR TEUR Balance as at 1 January 2016 18,821 - 3,765 6,181 28,767 Dividends to shareholders - - - (4,000) (4,000) Net loss for the year - - - (1,890) (1,890) Total comprehensive income - - - (1,890) (1,890) for the year Total changes - - - (5,890) (5,890) Balance as at 31 December 2016 18,821 - 3,765 291 22,877 Statutory Share Share reserve Retained capital premium fund earnings Total TEUR TEUR TEUR TEUR TEUR Balance as at 1 January 2015 18,821 - 3,765 5,535 28,121 Dividends to shareholders - - - (4,000) (4,000) Net profit for the year - - - 4,646 4,646 Total comprehensive income - - - 4,646 4,646 for the year Total changes - - - 646 646 Balance as at 31 December 2015 18,821 - 3,765 6,181 28,767 - 8 - Home Credit Slovakia, a.s.