Prehistory of Salishan Languages M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tsimshian Dictionary

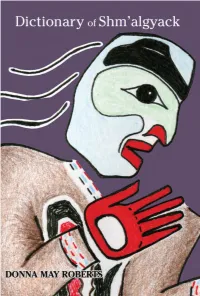

Dictionary of Shm’algyack Donna May Roberts Sealaska Heritage Institute Juneau, Alaska © 2009 by Sealaska Heritage Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 1440401195 EAN-13:9781440401190 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939132 Sealaska Heritage Institute One Sealaska Plaza, Suite 301 Juneau, Alaska 99801 907-463-4844 www.sealaskaheritage.org Printing: Create Space, Scotts Valley, CA, U.S.A. Front cover design: Kathy Dye Front cover artwork: Robert Hoffmann Book design and computational lexicography: Sean M. Burke Copy editing: Suzanne G. Fox, Red Bird Publishing, Inc., Bozeman, MT Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................... 1 Introduction ..................................... 3 Dictionary of Shm’algyack Shm’algyack to English ................ 7 English to Shm’algyack ............... 67 Dictionary of Shm'algyack - 1 aam verb to be fine, good, well PLURAL: am'aam Shm'algyack to ·Aam wila howyu. I’m feeling good. ·Na sheepg nakshu ashda 'guulda English shada dowl mahlda doctor hla aam wila waald gya'win. My wife was sick the other day but the doctor said she’s aab noun my father good now. ·Yagwa goom wunsh aabdu. My aamggashgaawt verb to be of father is hunting for deer. medium size, of a good size aad noun; verb net; to seine ·Aamggashgaawt ga yeeh. The King PLURAL: ga'aad salmon was of a good size. ·Geegsh Dzon shu aad dm hoyt hla aamhalaayt noun headdress, aadmhoant. John bought a new net mask, regalia, shaman’s mask; shaman for fishing. -

Toward the Reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: the Algonquian-Wakashan 110-Item Wordlist

Sergei L. Nikolaev Institute of Slavic studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow/Novosibirsk); [email protected] Toward the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: The Algonquian-Wakashan 110-item wordlist In the third part of my complex study of the historical relations between several language families of North America and the Nivkh language in the Far East, I present an annotated demonstration of the comparative data that was used in the lexicostatistical calculations to determine the branching and approximate glottochronological dating of Proto-Algonquian- Wakashan and its offspring; because of volume considerations, this data could not be in- cluded in the previous two parts of the present work and has to be presented autonomously. Additionally, several new Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan and Proto-Nivkh-Algonquian roots have been set up in this part of study. Lexicostatistical calculations have been conducted for the following languages: the reconstructed Proto-North Wakashan (approximately dated to ca. 800 AD) and modern or historically attested variants of Nootka (Nuuchahnulth), Amur Nivkh, Sakhalin Nivkh, Western Abenaki, Miami-Peoria, Fort Severn Cree, Wiyot, and Yurok. Keywords: Algonquian-Wakashan languages, Nivkh-Algonquian languages, Algic languages, Wakashan languages, Chimakuan-Wakashan languages, Nivkh language, historical phonol- ogy, comparative dictionary, lexicostatistics. The classification and preliminary glottochronological dating of Algonquian-Wakashan currently remain the same as presented in Nikolaev 2015a, Fig. 1 1. That scheme was generated based on the lexicostatistical analysis of 110-item basic word lists2 for one reconstructed (Proto-Northern Wakashan, ca. 800 A.D.) and several modern Algonquian-Wakashan lan- guages, performed with the aid of StarLing software 3. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas edited by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, and Daisy Rosenblum Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 Published as a sPecial Publication of language documentation & conservation language documentation & conservation Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 USA http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc university of hawai‘i Press 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822-1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors. 2010 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Cover design by Cameron Chrichton Cover photograph of salmon drying racks near Lime Village, Alaska, by Andrea L. Berez Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-8248-3530-9 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4463 Contents Foreword iii Marianne Mithun Contributors v Acknowledgments viii 1. Introduction: The Boasian tradition and contemporary practice 1 in linguistic fieldwork in the Americas Daisy Rosenblum and Andrea L. Berez 2. Sociopragmatic influences on the development and use of the 9 discourse marker vet in Ixil Maya Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, and María Luz García 3. Classifying clitics in Sm’algyax: 33 Approaching theory from the field Jean Mulder and Holly Sellers 4. Noun class and number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-historical 57 research and respecting speakers’ rights in fieldwork Logan Sutton 5. The story of *o in the Cariban family 91 Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, and Sérgio Meira 6. Multiple functions, multiple techniques: 125 The role of methodology in a study of Zapotec determiners Donna Fenton 7. -

Kwakwaka'wakw Storytelling: Preserving Ancient Legends

MARCUS CHALMERS VERONIKA KARSHINA CARLOS VELASQUEZ KWAKWAKA'WAKW STORYTELLING: PRESERVING ANCIENT LEGENDS ADVISORS: SPONSOR: Professor Creighton Peet David Neel Dr. Thomas Balistrieri This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely published these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, seehttp://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects Image: Neel D. (n.d.) Crooked Beak KWAKWAKA'WAKW i STORYTELLING Kwakwaka'wakw Storytelling: Reintroducing Ancient Legends An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science. Submitted by: Marcus Chalmers Veronika Karshina Carlos Velasquez Submitted to: David A. Neel, Northwest Coast native artist, author, and project sponsor Professor Creighton Peet Professor Thomas Balistrieri Date submitted: March 5, 2021 This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely published these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects ABSTRACT ii ABSTRACT Kwakwaka'wakw Storytelling: Preserving Ancient Legends Neel D. (2021) The erasure of Kwakwaka'wakw First Nations' rich culture and history has transpired for hundreds of years. This destruction of heritage has caused severe damage to traditional oral storytelling and the history and knowledge interwoven with this ancient practice. Under the guidance of Northwest Coast artist and author David Neel, we worked towards reintroducing this storytelling tradition to contemporary audiences through modern media and digital technologies. -

A Guide to Source Material on Extinct North American Indian Languages Author(S): Kenneth Croft Source: International Journal of American Linguistics, Vol

A Guide to Source Material on Extinct North American Indian Languages Author(s): Kenneth Croft Source: International Journal of American Linguistics, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct., 1948), pp. 260-268 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1262881 . Accessed: 22/03/2011 08:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of American Linguistics. http://www.jstor.org A GUIDE TO SOURCE MATERIAL ON EXTINCT NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES KENNETHCROFT INDIANAUNIVERSITY 0. -

Growing up Indian: an Emic Perspective

GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTIVE By GEORGE BUNDY WASSON, JR. A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy june 2001 ii "Growing Up Indian: An Ernie Perspective," a dissertation prepared by George B. Wasson, Jr. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. This dissertation is approved and accepted by: Committee in charge: Dr. jon M. Erlandson, Chair Dr. C. Melvin Aikens Dr. Madonna L. Moss Dr. Rennard Strickland (outside member) Dr. Barre Toelken Accepted by: ------------------------------�------------------ Dean of the Graduate School iii Copyright 2001 George B. Wasson, Jr. iv An Abstract of the Dissertation of George Bundy Wasson, Jr. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology to be taken June 2001 Title: GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTN E Approved: My dissertation, GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTN E describes the historical and contemporary experiences of the Coquille Indian Tribe and their close neighbors (as manifested in my own family), in relation to their shared cultures, languages, and spiritual practices. I relate various tribal reactions to the tragedy of cultural genocide as experienced by those indigenous groups within the "Black Hole" of Southwest Oregon. My desire is to provide an "inside" (ernie) perspective on the history and cultural changes of Southwest Oregon. I explain Native responses to living primarily in a non-Indian world, after the nearly total loss of aboriginal Coquelle culture and tribal identity through v decimation by disease, warfare, extermination, and cultural genocide through the educational policies of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. -

Reconstructing Proto-Sahaptian Sounds

Reconstructing Proto-Sahaptian Sounds Noel Rude Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Sahaptin and the mutually unintelligible Nez Perce comprise the Sahaptian language family. This paper attempts to reconstruct the sound system of the parent language of that family. There is little dialect variation in the available data for Nez Perce, whereas Sahaptin divides into three definable dialect clusters: Columbia River (Umatilla, Tenino, Celilo, etc.); Northwest (Klickitat, Upper Cowlitz, Yakima, etc.); Northeast (Priest Rapids, Walla Walla, Palouse, etc.). Various features distinguish the dialects, e.g., long vowels derived from certain VCV sequences are more common in the Northern dialects and in Nez Perce, the Northeast dialects and Nez Perce are more likely to preserve the glottal stop, and the palatalization of *k is most extensive in the Columbia River dialects. The reconstructions proposed here are, as always, more or less tentative. Unless otherwise indicated the examples labeled Sahaptin (S) are from Umatilla.1 Figure 1. The Sahaptian language family Proto-Sahaptian Nez Perce Sahaptin Columbia River Northern Northwest Northeast 1 For the connection between Sahaptin and Nez Perce, see Aoki (1962), Rigsby (1965), Rigsby and Silverstein (1969), and Rude (1996, 2006). For the relationship with Plateau Penutian, see Aoki (1963), Rude (1987), and Pharis (2006). For a possible relationship within the broader Penutian macro-family, see DeLancey & Golla (1979) and Mithun (1999), also Rude (2000) for a possible connection with Uto-Aztecan. For Sahaptin grammars, see Jacobs (1931), Millstein (ca. 1990a), Rigsby and Rude (1996), Rude (2009), and for published NW Sahaptin texts, see Jacobs (1929, 1934, 1937). Beavert and Hargus (2010) provide a dictionary of Yakima Sahaptin, Millstein (ca. -

(SANICH) CHINOOK JARGON TEXT 1 Dell Hymes University of Virginia

1 THOMAS PAUL'S 'SAMETL': VERSE ANALYSI S OF A (SANICH) CHINOOK JARGON TEXT 1 Dell Hymes University of Virginia I Questions as to the origin, development, and role of pidgin and creole languages include questions as to the patterning of discourse in them, Some such languages have b~n found to show regularity of patterning of the sort called 'measured verse', discoveroo first in a number of American Indian languages, especially of the North Pacific ~oast (Judith Berman (Kwagut), John Dunn (Tsimshian), myself (Alsea, Beila Coola, Chinookan, Kalapuya, Takelma), Virginia Hymes (Sahaptin), and Dale Kinkade (Chehalis». (For general discussion, ct. Hymes 1981, 1985b, 1987, ms). I have come upon such patterning in two languages of the PaCifiC, Hawaiian Pidgin English (a short text published by Derek Bickerton), and Kriol, a language of Australia (see Hymes 1988). The growing evidence of such patterning in distant and unrelated languages (Finnish, New Testament • rJ:j~.. Greek, West African French, Appalachian English, as well as American Indian languages such as Lakota, Ojibwe, Tonkawa, Zuni), together with the restricted set of alternative choices of patterning so far found, suggests something inherent and universal. I am Willing to believe that the impulse to such form may be inherent, a universal concomitant, or better, dimension of language. The restricted set of alternatives might suggest an innate modular baSiS, analogous to Chomsky's current approach, for the particulars as well as the dimension. A functional explanation, however, is also possible. If patterning is to infuse discourse with organization relationships, style woven fine, pairs and triads are the smallest alternative groupings. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Vowel Harmony in Two Even Dialects Dialects

400 220 Natalia Aralova Natalia Aralova Natalia Aralova Vowel harmony in two Even Vowel harmony in two Even dialects dialects Production and perception Production and perception This dissertation analyzes vowel systems in two dialects of Even, an endangered Northern Tungusic language spoken in Eastern Siberia. The data were collected during fieldwork in the Bystraia district of Central Kamchatka and in the village of Sebian-Küöl in Yakutia. The focus of the study is the Even system of vowel harmony, which in previous literature has been assumed to be robust. The central question concerns the number of vowel oppositions and the nature of the feature underlying the opposition between harmonic sets. The results of an acoustic study show a consistent pattern for only one acoustic parameter, namely F1, which can harmony in two Even dialects Vowel be phonologically interpreted as a feature [±height]. This acoustic study is supplemented by perception experiments. The results of the latter suggest that perceptually there is no harmonic opposition for high vowels, i.e., the harmonic pairs of high vowels have merged. Moreover, in the dialect of the Bystraia district certain consonants function as perceptual cues for the harmonic set of a word. In other words, the Bystraia Even harmony system, which was previously based on vowels, is being transformed into new oppositions among consonants. ISBN 978-94-6093-180-2 Vowel harmony in two Even dialects: Production and perception Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Even reindeer herder Anatoly Afanasyevich Solodikov, Central Kamchatka. -

COMPARING HUMANS and BIRDS by Daniel C. Mann a Dissertation

STABILIZING FORCES IN ACOUSTIC CULTURAL EVOLUTION: COMPARING HUMANS AND BIRDS by Daniel C. Mann A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 2019 DANIEL C. MANN All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. JULIETTE BLEVINS Date Chair of the Examining Committee GITA MARTOHARDJONO Date Executive Officer MARISA HOESCHELE DAVID C. LAHTI MICHAEL I. MANDEL Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract STABILIZING FORCES IN ACOUSTIC CULTURAL EVOLUTION: COMPARING HUMANS AND BIRDS By Daniel C. Mann Advisor: Professor Juliette Blevins Learned acoustic communication systems, like birdsong and spoken human language, can be described from two seemingly contradictory perspectives. On one hand, learned acoustic communication systems can be remarkably consistent. Substantive and descriptive generalizations can be made which hold for a majority of populations within a species. On the other hand, learned acoustic communication systems are often highly variable. The degree of variation is often so great that few, if any, substantive generalizations hold for all populations in a species. Within my dissertation, I explore the interplay of variation and uniformity in three vocal learning species: budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus), house finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), and humans (Homo sapiens). Budgerigars are well-known for their versatile mimicry skills, house finch song organization is uniform across populations, and human language has been described as the prime example of variability by some while others see only subtle variations of largely uniform system.