The Pacific Historian, Volume 30, Number 1 (1986)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

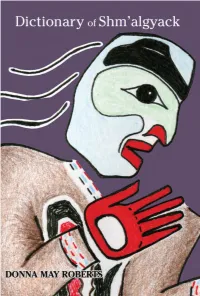

Tsimshian Dictionary

Dictionary of Shm’algyack Donna May Roberts Sealaska Heritage Institute Juneau, Alaska © 2009 by Sealaska Heritage Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 1440401195 EAN-13:9781440401190 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939132 Sealaska Heritage Institute One Sealaska Plaza, Suite 301 Juneau, Alaska 99801 907-463-4844 www.sealaskaheritage.org Printing: Create Space, Scotts Valley, CA, U.S.A. Front cover design: Kathy Dye Front cover artwork: Robert Hoffmann Book design and computational lexicography: Sean M. Burke Copy editing: Suzanne G. Fox, Red Bird Publishing, Inc., Bozeman, MT Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................... 1 Introduction ..................................... 3 Dictionary of Shm’algyack Shm’algyack to English ................ 7 English to Shm’algyack ............... 67 Dictionary of Shm'algyack - 1 aam verb to be fine, good, well PLURAL: am'aam Shm'algyack to ·Aam wila howyu. I’m feeling good. ·Na sheepg nakshu ashda 'guulda English shada dowl mahlda doctor hla aam wila waald gya'win. My wife was sick the other day but the doctor said she’s aab noun my father good now. ·Yagwa goom wunsh aabdu. My aamggashgaawt verb to be of father is hunting for deer. medium size, of a good size aad noun; verb net; to seine ·Aamggashgaawt ga yeeh. The King PLURAL: ga'aad salmon was of a good size. ·Geegsh Dzon shu aad dm hoyt hla aamhalaayt noun headdress, aadmhoant. John bought a new net mask, regalia, shaman’s mask; shaman for fishing. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Golden Circle Scenic 7 Days from Whitehorse

Golden Circle Scenic 7 days from Whitehorse Itinerary at a glance: Day 0: Arrival in Whitehorse Day 1: The Yukon - Miles Canyon, Emerald Lake, World's Smallest Desert, Carcross, Bennett Lake, Yukon Suspension Bridge, and International Falls Day 2: Skagway - White Pass Railroad and Taiya River Scenic float Day 3: Juneau - Whale Watching, Mendenhall Glacier, and Salmon Hatchery Day 4: Haines - Kroeschel Wildlife Refuge, Klukwan Native Village, and Float through Bald Eagle Preserve Day 5: Haines - Canoe on Chilkoot Lake, Raptor Center, and Distillery Tasting Day 6: The Yukon - Chilkat Mountains, Kathleen Lake, Million Dollar Falls, Tatshenshini River, Kluane National Park Visitor Center, Yukon River, and Whitehorse Day 7: Departure from Whitehorse Day 0: Arrival Day Upon your arrival into Whitehorse, your guide will be waiting to transfer you to your hotel. After you are settled, you will meet with your guide and travelling companions to discuss the itinerary. Time will be confirmed. On this arrival day, you will have free time to enjoy the Capitol of the Yukon. Your guide will let you know at what time to meet the next day to start your adventure through Alaska and the Yukon. Meals on your own. Day 1: The Yukon - Exploring Yukon, British Columbia, and Alaska en route to Skagway After breakfast, we will stroll along the Yukon River Boardwalk and through downtown Whitehorse. Along the way, we will learn about the Athabaskan culture and this supply post's important role during the Gold Rush. Grab a latte or a smoothie and watch the might waters of the Yukon River rush past. -

Results of Nass River Biological Surveys for The

RESULTS OF NASS RIVER BIOLOGICAL SURVEYS FOR THE YEARS 1956 AND 1957, I NCLUDING A PRELIMI NARY ASSESSMENT OF THE POSSIBLE EFFECTS OF THE PROPOSED HYDRO- ELECTRIC PROJECT Department of Fish eries, Canada Vancouver, B. C. June, 1958 SH349 Canada. DePa rtment of Fisheri A2 Results of Nass Rive r biolosic 58-02 a l surve~s for the ~ea ~s 1956 a nd 1957, includins a Prelimina r c l s assessment of t h e Possible ef f ect s of the P roposed h ~ dro -e l ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS MAR 2 0 tH89 LJl3F?Af~Y p J\(:: f Fi:~·: F~, ,~,l '')~~~ y '"" 111.. C"TA"i"Vl")l\.'il Page ·~~· .. ~--"•·-· .. "-·- ... \~,,,.f.... -.L .. ~.:1 .. Ail... l"tll 1. r:~ i ~:~; ~ -i ~.·~·: ~-·: ~, 2: ;.-.! r... ;.- -. -~ .. ;·: /\ j\. 1~; · DESCRIP~~ION OF SUHVEYS NJ\r--.:,.:.,i;-.,10, C~:-.:;T·i:..::;J COL\JMBIA: 3 CAN/\[)/\ v~,;r~ l:H(6 l. 1956 - Prel~ninary survey of the Upper Nase wate:r·~b.ed :tn con.junction with the Meziadin operation.it:! 3 2. 1957 = Crnrmie:t•cial i'ishery 9 f'i. sh-whee 1 oper•at:lons ~ spawning gr,cmnd survey~ 3 t~ 1956 = Survey results 4 5 Do DISCUSSION 13 lo The Effect of the Power Development on the Upstirei.\tm M.igrt:i.tion of' Salmon and Trout 13 2-0 Ef:tect on Spawning and R::iax•ing Areas 14 (a) Main Dam. {b) Meziadj.n Storage Dam (c) Bell-Irving Storage Dam 3o The Anticipated Effect of Flooding on Lake P:i:~oduotiv·:tty (a) Mez:iadin Iiake ( b) Bowse.r L1:1ke lto The gffect on Downstr•eam M:tgra.t:ton 16 (a.) Res:tdi..uRl:tsm (b) Predation Eo CONCLUSION 18 '. -

Canadian Volcanoes, Based on Recent Seismic Activity; There Are Over 200 Geological Young Volcanic Centres

Volcanoes of Canada 1 V4 C.J. Hickson and M. Ulmi, Jan. 3, 2006 • Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics Where do volcanoes occur? Driving forces • Volcano chemistry and eruption types • Volcanic Hazards Pyroclastic flows and surges Lava flows Ash fall (tephra) Lahars/Debris Flows Debris Avalanches Volcanic Gases • Anatomy of an Eruption – Mt. St. Helens • Volcanoes of Canada Stikine volcanic belt Presentation Outline Anahim volcanic belt Wells Gray – Clearwater volcanic field 2 Garibaldi volcanic belt • USA volcanoes – Cascade Magmatic Arc V4 Volcanoes in Our Backyard Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics In Canada, British Columbia and Yukon are the host to a vast wealth of volcanic 3 landforms. V4 How many active volcanoes are there on Earth? • Erupting now about 20 • Each year 50-70 • Each decade about 160 • Historical eruptions about 550 Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics • Holocene eruptions (last 10,000 years) about 1500 Although none of Canada’s volcanoes are erupting now, they have been active as recently as a couple of 4 hundred years ago. V4 The Earth’s Beginning Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 5 V4 The Earth’s Beginning These global forces have created, mountain Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics ranges, continents and oceans. 6 V4 continental crust ic ocean crust mantle Where do volcanoes occur? Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 7 V4 Driving Forces: Moving Plates Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 8 V4 Driving Forces: Subduction Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 9 V4 Driving Forces: Hot Spots Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 10 V4 Driving Forces: Rifting Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics Ocean plates moving apart create new crust. -

Native American Art Los Angeles I December 11, 2018

Native American Art Los Angeles I December 11, 2018 Native American Art Los Angeles | Tuesday December 11, 2018 at 11am BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES REGISTRATION 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard +1 323 850 7500 Ingmars Lindbergs, Director IMPORTANT NOTICE Los Angeles, CA 90046 +1 323 850 6090 (fax) [email protected] Please note that all customers, bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (415) 503 3393 irrespective of any previous activity with Bonhams, are required to PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit Kim Jarand, Specialist complete the Bidder Registration Friday December 7, www.bonhams.com/24850 [email protected] Form in advance of the sale. The 12pm to 5pm +1 (323) 436 5430 form can be found at the back Saturday December 8, Please note that telephone bids of every catalogue and on our 12pm to 5pm must be submitted no later than ILLUSTRATIONS website at www.bonhams.com Sunday December 9, 4pm on the day prior to the Front cover: Lot 394 and should be returned by email or 12pm to 5pm auction. New bidders must also Session page: Lot 362 post to the specialist department Monday December 10, provide proof of identity and or to the bids department at 9am to 11am address when submitting bids. [email protected] Tuesday December 11, Please contact client services 9am to 11am with any bidding inquiries. To bid live online and / or leave internet bids please go to www.bonhams.com/auctions/24850 SALE NUMBER: 24850 LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE and click on the Register to bid link Lots 300 - 606 Please email: at the top left of the page. -

First Nations Pronunciations

A Basic Guide to Names* Listed below are the First Nations Peoples as they are generally known today with a phonetic guide to common pronunciation. Also included here are names formerly given these groups, and the language families to which they belong. People Pronunciation Have Been Called Language Family Haida Hydah Haida Haida Ktunaxa Tun-ah-hah Kootenay Ktunaxa Tsimshian Sim-she-an Tsimshian Tsimshian Gitxsan Git-k-san Tsimshian Tsimshian Nisga'a Nis-gaa Tsimshian Tsimshian Haisla Hyzlah Kitimat Wakashan Heiltsuk Hel-sic Bella Bella Wakashan Oweekeno O-wik-en-o Kwakiutl Wakashan Kwakwaka'wakw Kwak-wak-ya-wak Kwakiutl Wakashan Nuu-chah-nulth New-chan-luth Nootka Wakashan Tsilhqot'in Chil-co-teen Chilcotin Athapaskan Dakelh Ka-kelh Carrier Athapaskan Wet'suwet'en Wet-so-wet-en Carrier Athapaskan Sekani Sik-an-ee Sekani Athapaskan Dunne-za De-ney-za Beaver Athapaskan Dene-thah De-ney-ta Slave(y) Athapaskan Tahltan Tall-ten Tahltan Athapaskan Kaska Kas-ka Kaska Athapaskan Tagish Ta-gish Tagish Athapaskan Tutchone Tuchon-ee Tuchone Athapaskan Nuxalk Nu-halk Bella Coola Coast Salish Coast Salish** Coast Salish Coast Salish Stl'atl'imc Stat-liem Lillooet Interior Salish Nlaka'pamux Ing-khla-kap-muh Thompson/Couteau Interior Salish Okanagan O-kan-a-gan Okanagan Interior Salish Secwepemc She-whep-m Shuswap Interior Salish Tlingit Kling-kit Tlingit Tlingit *Adapted from Cheryl Coull's "A Traveller's Guide to Aboriginal B.C." with permission of the publisher, Whitecap Books ** Although Coast Salish is not the traditional First Nations name for the people occupying this region, this term is used to encompass a number of First Nations Peoples including Klahoose, Homalco, Sliammon, Sechelth, Squamish, Halq'emeylem, Ostlq'emeylem, Hul'qumi'num, Pentlatch, Straits. -

New Available LNG Sites on Canada's West Coast

New Available LNG Sites on Canada’s West Coast Disclaimer This presentation contains information that is preliminary in nature and may be subject to change in the future. Forward looking statements involve risks and uncertainties because they relate to events and depend upon circumstances that will or may vary in the future. Actual outcomes may differ. Any party interested in pursuing the opportunities presented here should undertake its own research and due diligence to satisfy itself of the quality of the information presented within. 2 Contents Page Introduction 4 Welcome 5 The Nisga’a Nation – An Overview 6 Natural Gas Supply in Western Canada 11 Nisga’a Nation Sites for a Floating or Land-Based LNG Facility 15 Regional Infrastructure 28 Next Steps 37 Contacts 39 3 Introduction • The Nisga’a Nation wishes to attract sustainable economic development, including LNG projects, to our area. • Canada’s vast resources of natural gas are ideal as a new LNG supply source for global markets. • Suitable sites for LNG development along the west coast of Canada are limited due to the mountainous terrain and restricted access. • Some perceive that most, if not all, sites have already been selected by various parties for their LNG projects. • The Nisga’a Nation owns all or part of four first rate sites for development that have not previously been identified for LNG projects. • These sites offer unique opportunities as a result of the Nisga’a Treaty, our Nisga’a Government, our property interests and our unique environmental assessment rights. • This package is a preliminary description of available LNG sites on the Portland Inlet waterway, near the Nass River, on Canada’s west coast, north of Prince Rupert. -

Franz Boas and Tsimshian Mythology Ralph Maud Potlatch at Gitsegukla

n8 BC STUDIES ... I had been thinking about the book is aimed, will be able to critically glyphs all morning after finally being assess its lack of scholarship. This can ferried across" Too bad he didn't take only lead to entrenching preconceptions the time to speak with the Edgars, who about, and ignorance of, First Nations have intimate knowledge of the area in British Columbia. The sad thing is and the tliiy'aa'a of Clo-oose. that, although this result is no doubt Serious students will find little of the furthest thing from Johnson's value in this book, and it is unlikely intention, it will be the legacy of his that the general public, at whom the book. Transmission Difficulties: Franz Boas and Tsimshian Mythology Ralph Maud Burnaby: Talonbooks, 2000.174 pp. Illus. $16.95 paper. Potlatch at Gitsegukla: William Beynon's 1Ç45 Field Notebooks Margaret Anderson and Marjorie Halpin, Editors Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000. 283 pp. Illus., maps. $29.95 paper. REGNA DARNELL University of Western Ontario OTH VOLUMES REVIEWED here respects the integrity of Beynon's parti explore the present utility and cipant-observation documentation, B quality of Tsimshian archival simultaneously reassessing and con- and published materials. There the re textualizing it relative to other extant semblance ends. The scholarly methods work on the Gitksan and closely related and standpoints are diametrically op peoples. Beynon was invited to the pot- posed; a rhetoric of continuity and latches primarily in his chiefly capacity, respect for tradition contrasts sharply although he was also an ethnographer with one of revolutionary discontinuity. -

Fighting Language Endangerment

ON SM'ALGYAX (COAST TSIMSHIAN) (COAST ON SM'ALGYAX RESEARCH DIRECTED COMMUNITY Fighting Language Endangerment TONYA STEBBINS LA TROBE EBUREAU La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC 3086, Australia https://library.latrobe.edu.au/ebureau/ First published in 2003 by ELPR Publications Second edition published in Australia by La Trobe University © La Trobe University 2020 Second edition published 2020 Copyright Information Copyright in this work is vested in La Trobe University. Unless otherwise stated, material within this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Non Derivatives License. CC BY-NC-ND http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Fighting Language Endangerment: Community Directed Research on Sm'algyax (Coast Tsimshian) Tonya Stebbins ISBN: 978-0-6484681-3-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26826/1011 Other Information Designed by La Trobe eBureau Enquiries: [email protected] This ebook has been peer reviewed Cover photo and imprints: Adapted from 'Thuja plicata Vancouver' by abdallahh from Wikimedia Commons used under CC BY 2.0. ii Preface to the second edition This book explores a range of issues associated with working in a community directed project to prepare a dictionary for community use. In conjunction with my studies as a MA and then a PhD student in Linguistics at the University of Melbourne between 1995 and 1999, I approached the Tsimshian community proposing to work with them on preparing an updated and expanded dictionary for the community. My involvement with the Tsimshian community was supported by my PhD supervisor, Dr Jean Mulder, who had also completed her PhD working on Sm'algyax, the language of the community. -

Appendix 1 Page 1 Text of Section 503 of the Alaska National Interest

Appendix 1 Page 1 Text of Section 503 of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) Public Law 96-487 December 2, 1980 94 Stat. 2371 MISTY FJORDS AND ADMIRALTY ISLAND NATIONAL MONUMENTS §503. (a) There is hereby established within the Tongass National Forest, the Misty Fjords National Monument, containing approximately two million two hundred and eighty-five thousand acres of public lands as generally depicted on a map entitled "Misty Fjords National Monument Proposed", dated July 1980. (b) There is hereby established within the Tongass National Forest, the Admiralty Island National Monument, containing approximately nine hundred and twenty-one thousand acres of public lands as generally depicted on a map entitled "Admiralty Island National Monument Proposed", dated July 1980. (c) Subject to valid existing rights and except as provided in this section, the National Forest Monuments (hereinafter in this section referred to as the "Monuments") shall be managed by the Secretary of Agriculture as units of the National Forest System to protect objects of ecological, cultural, geological, historical, prehistorical, and scientific interest. (d) Within the Monuments, the Secretary shall not permit the sale of harvesting of timber: Provided, That nothing in this subsection shall prevent the Secretary from taking measures as may be necessary in the control of fire, insects, and disease. (e) For the purposes of granting rights-of-way to occupy, use or traverse public land within the Monuments pursuant to Title XI, the provisions -

“Wearing the Mantle on Both Shoulders”: an Examination of The

“Wearing the Mantle on Both Shoulders”: An Examination of the Development of Cultural Change, Mutual Accommodation, and Hybrid Forms at Fort Simpson/Laxłgu‟alaams, 1834-1862 by Marki Sellers B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 2005 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History © Marki Sellers, 2010 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee “Wearing the Mantle on Both Shoulders”: An Examination of the Development of Cultural Change, Mutual Accommodation, and Hybrid Forms at Fort Simpson/Laxłgu‟alaams, 1834-1862 by Marki Sellers B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 2005 Supervisory Committee Dr. John Lutz, (Department of History) Co-Supervisor Dr. Lynne Marks, (Department of History) Co-Supervisor Dr. Wendy Wickwire, (Department of History) Departmental Member iii Supervisory Committee Dr. John Lutz, Co-Supervisor (Department of History) Dr. Lynne Marks, Co-Supervisor (Department of History) Dr. Wendy Wickwire, Departmental Member (Department of History) ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the relationships between newcomers of Fort Simpson, a HBC post that operated on the northern Northwest Coast of what is now British Columbia, and Ts‟msyen people from 1834 until 1862. Through a close analysis of fort journals and related documents, I track the relationships between the Hudson‟s Bay Company newcomers and the Ts‟msyen peoples who lived in or around the fort. Based on the journal and some other accounts, I argue that a mutually intelligible – if not equally understood – world evolved at this site.