Tsimshian Stories 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

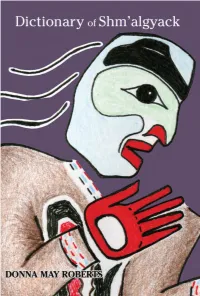

Tsimshian Dictionary

Dictionary of Shm’algyack Donna May Roberts Sealaska Heritage Institute Juneau, Alaska © 2009 by Sealaska Heritage Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 1440401195 EAN-13:9781440401190 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939132 Sealaska Heritage Institute One Sealaska Plaza, Suite 301 Juneau, Alaska 99801 907-463-4844 www.sealaskaheritage.org Printing: Create Space, Scotts Valley, CA, U.S.A. Front cover design: Kathy Dye Front cover artwork: Robert Hoffmann Book design and computational lexicography: Sean M. Burke Copy editing: Suzanne G. Fox, Red Bird Publishing, Inc., Bozeman, MT Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................... 1 Introduction ..................................... 3 Dictionary of Shm’algyack Shm’algyack to English ................ 7 English to Shm’algyack ............... 67 Dictionary of Shm'algyack - 1 aam verb to be fine, good, well PLURAL: am'aam Shm'algyack to ·Aam wila howyu. I’m feeling good. ·Na sheepg nakshu ashda 'guulda English shada dowl mahlda doctor hla aam wila waald gya'win. My wife was sick the other day but the doctor said she’s aab noun my father good now. ·Yagwa goom wunsh aabdu. My aamggashgaawt verb to be of father is hunting for deer. medium size, of a good size aad noun; verb net; to seine ·Aamggashgaawt ga yeeh. The King PLURAL: ga'aad salmon was of a good size. ·Geegsh Dzon shu aad dm hoyt hla aamhalaayt noun headdress, aadmhoant. John bought a new net mask, regalia, shaman’s mask; shaman for fishing. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

First Nations Pronunciations

A Basic Guide to Names* Listed below are the First Nations Peoples as they are generally known today with a phonetic guide to common pronunciation. Also included here are names formerly given these groups, and the language families to which they belong. People Pronunciation Have Been Called Language Family Haida Hydah Haida Haida Ktunaxa Tun-ah-hah Kootenay Ktunaxa Tsimshian Sim-she-an Tsimshian Tsimshian Gitxsan Git-k-san Tsimshian Tsimshian Nisga'a Nis-gaa Tsimshian Tsimshian Haisla Hyzlah Kitimat Wakashan Heiltsuk Hel-sic Bella Bella Wakashan Oweekeno O-wik-en-o Kwakiutl Wakashan Kwakwaka'wakw Kwak-wak-ya-wak Kwakiutl Wakashan Nuu-chah-nulth New-chan-luth Nootka Wakashan Tsilhqot'in Chil-co-teen Chilcotin Athapaskan Dakelh Ka-kelh Carrier Athapaskan Wet'suwet'en Wet-so-wet-en Carrier Athapaskan Sekani Sik-an-ee Sekani Athapaskan Dunne-za De-ney-za Beaver Athapaskan Dene-thah De-ney-ta Slave(y) Athapaskan Tahltan Tall-ten Tahltan Athapaskan Kaska Kas-ka Kaska Athapaskan Tagish Ta-gish Tagish Athapaskan Tutchone Tuchon-ee Tuchone Athapaskan Nuxalk Nu-halk Bella Coola Coast Salish Coast Salish** Coast Salish Coast Salish Stl'atl'imc Stat-liem Lillooet Interior Salish Nlaka'pamux Ing-khla-kap-muh Thompson/Couteau Interior Salish Okanagan O-kan-a-gan Okanagan Interior Salish Secwepemc She-whep-m Shuswap Interior Salish Tlingit Kling-kit Tlingit Tlingit *Adapted from Cheryl Coull's "A Traveller's Guide to Aboriginal B.C." with permission of the publisher, Whitecap Books ** Although Coast Salish is not the traditional First Nations name for the people occupying this region, this term is used to encompass a number of First Nations Peoples including Klahoose, Homalco, Sliammon, Sechelth, Squamish, Halq'emeylem, Ostlq'emeylem, Hul'qumi'num, Pentlatch, Straits. -

The Pacific Historian, Volume 30, Number 1 (1986)

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons The aP cific iH storian Western Americana 1986 The aP cific iH storian, Volume 30, Number 1 (1986) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pac-historian Recommended Citation "The aP cific iH storian, Volume 30, Number 1 (1986)" (1986). The Pacific isH torian. 116. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pac-historian/116 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Americana at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP cific Historian by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Native Missionaries of the North Pacific Coast Philip McKay and Others E. Palmer Patterson Indian: A History Since 1500 (1972) and Mis sion on the Nass: The Evangelization of the Nishga (1860-1890) (1982). His current re E. Palmer Patterson is Associate Professor search is on the history of the Nishga Indi of History at the University of Waterloo, ans of British Columbia in contact with Ontario, Canada. Among his works on Europeans during the second half of the Canadian native peoples are The Canadian nineteenth century. White missionaries and their native converts. N WRITING THE HISTORY of nineteenth sion is seen as an example of European or Euro century Christian missions the tendency has American/Euro-Canadian cultural expansion and Ibeen to deal primarily with the European and its techniques of dissemination. However, native Euro-American or Euro-Canadian missionarie·s cultures have not always been destroyed, though and their exploits- as adventure, devotion , sac they have often been drastically altered . -

Franz Boas and Tsimshian Mythology Ralph Maud Potlatch at Gitsegukla

n8 BC STUDIES ... I had been thinking about the book is aimed, will be able to critically glyphs all morning after finally being assess its lack of scholarship. This can ferried across" Too bad he didn't take only lead to entrenching preconceptions the time to speak with the Edgars, who about, and ignorance of, First Nations have intimate knowledge of the area in British Columbia. The sad thing is and the tliiy'aa'a of Clo-oose. that, although this result is no doubt Serious students will find little of the furthest thing from Johnson's value in this book, and it is unlikely intention, it will be the legacy of his that the general public, at whom the book. Transmission Difficulties: Franz Boas and Tsimshian Mythology Ralph Maud Burnaby: Talonbooks, 2000.174 pp. Illus. $16.95 paper. Potlatch at Gitsegukla: William Beynon's 1Ç45 Field Notebooks Margaret Anderson and Marjorie Halpin, Editors Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000. 283 pp. Illus., maps. $29.95 paper. REGNA DARNELL University of Western Ontario OTH VOLUMES REVIEWED here respects the integrity of Beynon's parti explore the present utility and cipant-observation documentation, B quality of Tsimshian archival simultaneously reassessing and con- and published materials. There the re textualizing it relative to other extant semblance ends. The scholarly methods work on the Gitksan and closely related and standpoints are diametrically op peoples. Beynon was invited to the pot- posed; a rhetoric of continuity and latches primarily in his chiefly capacity, respect for tradition contrasts sharply although he was also an ethnographer with one of revolutionary discontinuity. -

Tsimshian Wil'naat'ał and Society

Tsimshian Wil’naat’ał and Society: Historicising Tsimshian Social Organization James A. McDonald Introduction ot far from Gitxaała are the people who live inside the mists of the Skeena River. Connected to Gitxaała by the familial ties of kinship and chiefly designs, theN eleven Aboriginal communities of the lower Skeena River also are part of the Tsimshian Nation. The prevailing understanding of Tsimshian social organization has long been clouded in a fog of colonialism. The resulting interpretation of the indigenous prop- erty relations marches along with the new colonial order but is out of step with values expressed in the teachings of the wilgagoosk – the wise ones who archived their knowledge in the historical narratives called adaawx and other oral sources. This chapter reviews traditional and contemporary Tsimshian social structures to argue that the land owning House (Waap1) and Clan (Wil’naat’ał) have been demoted in importance in favour of the residential and political communities of the tribe (galts’ap). Central to my argument is a critical analysis of the social importance of the contemporary Indian Reserve villages that is the basis of much political, cultural, and economic activity today. The perceived centrality of these settlements and their associated tribes in Tsimshian social structure has become a historical canon accepted by missionaries, politicians, civil servants, historians, geographers, archaeologists, and many “armchair” anthropologists. This assumption is a convention that loosens the Aboriginal ties to the land and resources and is attractive for the colonial society. It is a belief that has been normalized within the colonized worldview as the basis for relationships in civil society. -

1 Paper Presented at the Sharing Our Knowledge

PAPER PRESENTED AT THE SHARING OUR KNOWLEDGE TSIMSHIAN, HAIDA, AND TLINGIT CLAN CONFERENCE March 21-25, 2007, Sitka, Alaska --------------------------------- Tlingit Music: Past, Present and Future: What has Survived the Colonial Period? By Maria Shaan Tláa Williams “To resist is to retrench in the margins, retrieve what we were and remake ourselves” Linda Tuhiwai Smith, 2001:4 Waa sa ituwatee? [Hello and how are you?] Maria Shaan Tláa Williams yoo xat duwasaakw [My name is Maria Williams] Yeil naax xat sitee [I am of the Raven moiety] Deisitaan naax xat sitee [I am of the Beaver clan] Dakl’aweidi yadix xat siteee [I am a child of the Killer Whale clan] Atlin kwaan aya xat [I am of the Atlin Lake people] Anchorage and Carcross/Tagish First Nations aya xat [I am also of the Carcross/Tagish First Nations people and the Anchorage people] My name is Maria Williams, I am Raven of the Deisitaan clan and a child of the Killer Whale. I am of the Big Lake people, the Atlein Kwaan, and from Anchorage and of the Carcross/Tagish First Nations people. My father was Aweix Bill Williams (Dakl’aweidi) and my mother Sneeaxt Marilyn Williams (Dleit Kaa and Black Foot) who was adopted by the Deisitaan people of Carcross/Tagish First Nations. Gunalsheesh deishitaan! 1 Gunalcheesh and Thank you for allowing me to speak here people of SITKA Sheey At‘ika Kwaan and our conference organizers Steve Henrickson and Andy Hope III. I am deeply honored to be in your homeland and to be here with such esteemed colleagues. -

Principles and Practicalities of Corpus Design in Language Retrieval: Issues in the Digitization of the Beynon Corpus of Early Twentieth-Century Sm’Algyax Materials

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 34-59 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4466 Principles and Practicalities of Corpus Design in Language Retrieval: Issues in the Digitization of the Beynon Corpus of Early Twentieth-Century Sm’algyax Materials Tonya N. Stebbins La Trobe University and Birgit Hellwig University of Erfurt and La Trobe University This paper describes a pilot project to develop a machine-readable corpus of early twenti- eth-century Sm’algyax texts from a large collection of handwritten manuscripts collected by the Tsimshian ethnographer and chief William Beynon. The project seeks to ensure that the materials produced are maximally accessible to the Tsimshian community. It relates established principles for corpus design to practical issues in language retrieval, recogniz- ing that the corpus will likely function as an intermediate stage between the original manu- scripts and any language materials developed by the community. The paper is addressed primarily to linguists working on language retrieval projects but may also be of use to communities who are working with linguists, as it provides insight into the concerns and preoccupations that linguists bring to such tasks. 1. INTRODUCTION. This paper describes a pilot project exploring the practicalities of retrieving and converting a large body of Sm’algyax manuscript texts into an electronic machine-readable format to use in language-related activities within the community. We identify a range of practical issues in the interaction between linguists and community members that will need to be addressed if the project is to expand and continue.1 Sm’algyax is the ancestral language of the Tsimshian Nation, whose territory is on the north coast of British Columbia, Canada. -

Alaska Native

Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian | Cultures of Alaska | Education & Programs | Alaska Native DEC FEB MAR ⍰ ⍰ 158 captures 19 f 5 Feb 2013 - 30 Dec 2018 2013 2014 2015 ⍰ About this capture HOME RESOURCES MEDIA ROOM F.A.Q. HOW TO GET HERE JOBS CONTACT US Quick Links ONLINE DONATE SIGN UP FOR PLAN YOUR VISIT EDUCATION & PROGRAMS EVENTS FACILITY RENTALS ABOUT US GIFT SHOP NOW! NEWSLETTER MEMBERSHIP Home Education & Programs Cultures of Alaska Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian Education & PROGRAMS Workshops And Classes EYAK, TLINGIT, HAIDA AND TSIMSHIAN CULTURES OF Language Project ALASKA Art Place ALASKA'S NATIVE PEOPLE ARE DIVIDED INTO 11 DISTINCT CULTURES, SPEAKING 11 DIFFERENT LANGUAGES AND TWENTY-TWO DIFFERENT Teachers DIALECTS. IN ORDER TO TELL THE STORIES OF THIS DIVERSE Youth POPULATION, THE ALASKA NATIVE HERITAGE CENTER IS ORGANIZED BASED ON FIVE CULTURE GROUPINGS, WHICH DRAW UPON Cultures of Alaska CULTURAL SIMILARITIES OR GEOGRAPHIC PROXIMITY. Athabascan Unangax and Alutiiq(Sugpiaq) Tweet Yup'ik And Cup'ik Inupiaq and St. Lawrence Island Yupik The Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian - Who We Are Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian Exhibits & Collections The Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian share a common and similar Northwest Coast Culture with important differences in language and clan system. Anthropologists use the term "Northwest Coast Culture" to define the Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian cultures, as well as that of other peoples indigenous to the Pacific coast, extending as far as northern Oregon. The Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian have a complex social system consisting of moieties, phratries and clans. Eyak, Tlingit and Haida divide themselves into moieties, while the Tsimshian divide into phratries. -

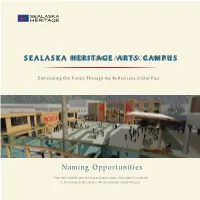

Naming Opportunities

SEALASKA HERITAGE ARTS CAMPUS Envisioning Our Future Through the Reflections of Our Past Naming Opportunities From the handheld adze to the grand cedar posts, every piece is essential in the making of the campus. We are honored to build with you. FIRST FLOOR Dear Friend: Thank you for your interest in joining with us to reach our goal to make Juneau the Northwest Coast Arts Capital and to designate Northwest Coast art a national treasure. In phase one, we built the Walter Soboleff Building, an educational space for the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian, as well as the general public, that opened 3 1 in 2015. Phase two, the Sealaska Heritage Arts Campus, will include classrooms and studio spaces that will bear the names of significant Alaska Native people who 4 have contributed to our state. The campus will also include plaques identifying the 2 people and entities who generously donated to make these spaces possible.* We offer the following options for your consideration: GIFT VALUE SPACE MAP NUMBER Atrium $150,000 $2,000,000 Courtyard & Totem Pole 12 Donor will be supporting a display of exquisite examples of Northwest Coast art in a very prominent area. $1,000,000 Robert Davidson Wood Carving Studio 1 $1,000,000 Jennie Thlunaut Fiber & Textile Studio 4 $750,000 Outdoor Covered Performing Space 11 Robert Davidson Wood Carving Studio Jennie Thlunaut Fiber & Textile Studio $500,000 Metal Arts Studio 5 $250,000 David A. Boxley Artist-in-Residence Studio 2 $1,000,000 $1,000,000 Donor will be supporting art practices such Donor will be supporting art practices such as $150,000 Atrium 3 as the making of totem poles, dugout canoes, the making of basketry and Chilkat and Ravenstail masks, and bentwood boxes, art forms for which robes, art forms unique to the Tlingit, Haida, and $50,000 (per piece) Faces of Alaska 10 the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian are known Tsimshian. -

Tsimshian Involvement in the Forest Sector

Forests for the Future Unit 4 Tsimshian Involvement in the Forest Sector by Paul Orlowski Tsimshian Involvement in the Forest Sector by Paul Orlowski Forests for the Future, Unit 4 © 2003 The University of British Columbia This is one of a series of curriculum materials developed as part of the Forests for the Future project, funded by Forest Renewal BC Research Award PAR02002-23 Project Leader: Charles R. Menzies, Ph.D Information about the project is available at www.ecoknow.ca Design and Production: Half Moon Communications Permission is granted for teachers to download and make copies for their own use, and to make use of the blackline master for use in their own classrooms. Any other use requires permission of the Department of Anthropology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC. Acknowledgements: Thanks to the Forests for the Future project team and all of the various teachers, students, community members, and others who have contributed to making this project a success. A special thanks to Ken Campbell for his work preparing for publication. Forests for the Future ¥ Unit 4 Contents Introduction . .4 Prescribed Learning Outcomes . .7 Unit Outline . .9 Lesson 1 The History of Tsimshian Involvement in Forestry . .10 Lesson 2 Tsimshian Women and Forestry . .20 Lesson 3 The Pros and Cons of Waged Labour . .27 Lesson 4 Forestry and the Future: The Tsimshian in a Post-Treaty Environment . .32 3 Forests for the Future ¥ Unit 4 Tsimshian Involvement in the Forest Sector by Paul Orlowski INTRODUCTION Rationale Knowledge of First Nations cultures among non-Aboriginal Canadians has increased in recent years. -

David Boxley Tsimshian Artist

David Boxley Tsimshian Artist "Artists from long ago inspire new generations of Native people to carry on the traditions which they began. I’m determined and dedicated to become the finest artist I can be, while at the same time helping to revitalize and carry on the rich culture of my tribe." !David Boxley is a Tsimshian artist from Metlakatla, Alaska. Born in 1952, he was raised by his grandparents. From them he learned many Tsimshian traditions including S’malgyak (the Tsimshian language). In 1974, he earned his Bachelor of Science degree from Seattle Pacific University and began his professional career as a teacher and basketball coach at middle schools and high schools in Alaska and Washington. In 1979, while teaching in Metlakatla, David began devoting a considerable amount of time to the study of traditional Tsimshian carving. Researching ethnographic material and studying artifacts in museum collections, David learned the traditional carving methods of his ancestors. In 1986, he made a career decision to leave the job security of teaching and to devote all of his energy toward carving and research, and revitalizing the cultural traditions of his people. !David Boxley has become a nationally recognized artist who has shown in the United States and Europe. He is the first Alaskan Tsimshian artist to achieve national and international prominence. In all of David’s work he emphasizes Tsimshian style. Having carved 46 totem poles in the last twenty five years, David is particularly well respected for his totem pole carving. !Most important to David is his deep involvement in the rebirth of Tsimshian culture.