Franz Boas and Tsimshian Mythology Ralph Maud Potlatch at Gitsegukla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-War Anthropology Andrew Nurse

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 17:02 Scientia Canadensis Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine Revue canadienne d'histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine The Ambiguities of Disciplinary Professionalization: The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-war Anthropology Andrew Nurse Volume 30, numéro 2, 2007 Résumé de l'article La professionnalisation de l’anthropologie canadienne dans la première moitié URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/800546ar du 20e siècle fut étroitement liée à la matrice de l’État fédéral, tout d’abord par DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/800546ar l’entremise de la division anthropologique de la Comission géologique du Canada, et ensuite par le biais du Musée national. Les anthropologues de l’État Aller au sommaire du numéro possèdent alors un statut professionnel ambigu à la fois comme fonctionnaires et comme anthropologues dévoués aux impératifs méthodologiques et disciplinaires de la science sociale moderne, mais limités et guidés par les Éditeur(s) exigences du service civil. Leur position au sein de l’État a favorisé le développement de la discipline, mais a également compromis l’autonomie CSTHA/AHSTC disciplinaire. Pour faire face aux limites imposées par l’État au soutien de leur discipline, les anthropologues de la fonction publique ont entretenu différents ISSN réseaux culturels, intellectuels, et comercialement-orientés qui ont servi à soutenir les nouveaux développements de leur champ, particulièrement dans 0829-2507 (imprimé) l’étude du folklore. Le présent essai examine ces dynamiques et suggère que le 1918-7750 (numérique) développement disciplinaire de l’anthropologie ne crée pas de dislocations entre la recherche professionnelle et la société civile. -

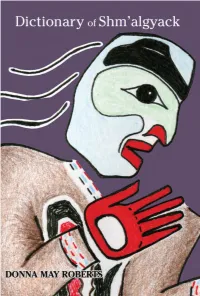

Tsimshian Dictionary

Dictionary of Shm’algyack Donna May Roberts Sealaska Heritage Institute Juneau, Alaska © 2009 by Sealaska Heritage Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 1440401195 EAN-13:9781440401190 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939132 Sealaska Heritage Institute One Sealaska Plaza, Suite 301 Juneau, Alaska 99801 907-463-4844 www.sealaskaheritage.org Printing: Create Space, Scotts Valley, CA, U.S.A. Front cover design: Kathy Dye Front cover artwork: Robert Hoffmann Book design and computational lexicography: Sean M. Burke Copy editing: Suzanne G. Fox, Red Bird Publishing, Inc., Bozeman, MT Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................... 1 Introduction ..................................... 3 Dictionary of Shm’algyack Shm’algyack to English ................ 7 English to Shm’algyack ............... 67 Dictionary of Shm'algyack - 1 aam verb to be fine, good, well PLURAL: am'aam Shm'algyack to ·Aam wila howyu. I’m feeling good. ·Na sheepg nakshu ashda 'guulda English shada dowl mahlda doctor hla aam wila waald gya'win. My wife was sick the other day but the doctor said she’s aab noun my father good now. ·Yagwa goom wunsh aabdu. My aamggashgaawt verb to be of father is hunting for deer. medium size, of a good size aad noun; verb net; to seine ·Aamggashgaawt ga yeeh. The King PLURAL: ga'aad salmon was of a good size. ·Geegsh Dzon shu aad dm hoyt hla aamhalaayt noun headdress, aadmhoant. John bought a new net mask, regalia, shaman’s mask; shaman for fishing. -

The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-War Anthropology Andrew Nurse

Document generated on 09/30/2021 5:47 p.m. Scientia Canadensis Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine Revue canadienne d'histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine The Ambiguities of Disciplinary Professionalization: The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-war Anthropology Andrew Nurse Volume 30, Number 2, 2007 Article abstract The professionalization of Canadian anthropology in the first half of the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/800546ar twentieth century was tied closely to the matrix of the federal state, first DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/800546ar though the Anthropology Division of the Geological Survey of Canada and then the National Museum. State anthropologists occupied an ambiguous See table of contents professional status as both civil servants and anthropologists committed to the methodological and disciplinary imperatives of modern social science but bounded and guided by the operation of the civil service. Their position within Publisher(s) the state served to both advance disciplinary development but also compromised disciplinary autonomy. To address the boundaries the state CSTHA/AHSTC imposed on its support for anthropology, state anthropologists cultivated cultural, intellectual, and commercially-oriented networks that served to ISSN sustain new developments in their field, particularly in folklore. This essay examines these dynamics and suggests that anthropology's disciplinary 0829-2507 (print) development did not create a disjunctive between professionalized scholarship 1918-7750 (digital) and civil society. Explore this journal Cite this article Nurse, A. (2007). The Ambiguities of Disciplinary Professionalization: The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-war Anthropology. Scientia Canadensis, 30(2), 37–53. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

George Woodcock's Peoples of the Coast: a Review Article* ROBERT D

George Woodcock's Peoples of the Coast: A Review Article* ROBERT D. LEVINE AND PETER L. MAGNAIR The appearance of George Woodcock's Peoples of the Coast ought to be a source of dismay for social scientists throughout the Northwest — and beyond the Northwest as well, for the willingness of publishers to print such volumes is certainly not confined to this one region. Woodcock's survey of cultures and culture categories on the Northwest Coast is one of the worst discussions of this subject matter available. Thus the need still exists for a non-technical book on Native peoples of the Coast, written for an intelligent lay audience willing to read with thought and care, synthe sizing the knowledge gained by investigators during the past century. Some of the finest fieldworkers in the history of North American ethnology carried out their best research in the Pacific Northwest: Franz Boas, Frederica de Laguna, Viola Garfield, John Swanton and Erna Gunther. Much of this work has been inaccessible to the non-specialist both because of the relative rareness of the original publications outside university libraries and because of the technical difficulty of the publications them selves, whose authors recorded, in minute detail, the tremendous com plexity of coastal societies. A summary and integration of the incredible mass of information we currently possess — and the questions which are still open and seriously debated — obviously would be very welcome. It is impossible for Woodcock's book to fulfill this role. Peoples of the Coast is so shot through with basic errors of fact and major misinterpre tations that another fair-sized volume would be required to list and discuss them all. -

Gitxaała Use and Occupancy in the Area of the Proposed Northern Gateway Pipeline Tanker Routes

Gitxaała Use and Occupancy in the area of the proposed Northern Gateway Pipeline Tanker Routes Prepared on behalf of Gitxaała Nation Charles R. Menzies, PhD December 18, 2011 Table of Contents Gitxaała Use and Occupancy in the area of the proposed Northern Gateway Pipeline Tanker Routes......................................................................................................... 0 1. Qualifications.................................................................................................................................2 2. Major sources of knowledge with respect to Gitxaała .....................................................3 3. The transmission of Gitxaala oral history, culture, language and knowledge ........6 3.1 Basis of evidence......................................................................................................................................6 3.2 Oral history and the transmission of narratives ........................................................................7 4. An overview of the early history of contact between Europeans and the Gitxaała. .............................................................................................................................................................. 10 5. An Ethnographic Description of Gitxaała.......................................................................... 11 5.1 Gitxaała Language ................................................................................................................................ 11 5.2 Social organization -

Marius Barbeau and Musical Performers Elaine Keillor

Marius Barbeau and Musical Performers Elaine Keillor Abstract: One of Marius Barbeau’s important contributions to heightening awareness of folk music traditions in Canada was his organization and promotion of concerts. These concerts took different forms and involved a range of performers. Concert presentations of folk music, such as those that Barbeau initiated called the Veillées du bon vieux temps, often and typically included a combination of performers. This article examines Barbeau’s “performers,” including classically educated musicians and some of his most prolific, talented informants. Barbeau and Juliette Gaultier Throughout Barbeau’s career as a folklorist, one of his goals was to use trained Canadian classical musicians as folk music performers, thereby introducing Canada’s rich folk music heritage to a broader public. This practice met with some mixed reviews. There are suggestions that he was criticized for depending on an American singer, Loraine Wyman,1 in his early presentations. Certainly, in his first Veillées du bon vieux temps, he used Sarah Fischer (1896-1975), a French-born singer who had made a highly praised operatic debut in 1918 at the Monument national in Montreal. But in 1919, she returned to Europe to pursue her career. Since she was no longer readily available for Barbeau’s efforts, he had to look elsewhere. One of Barbeau’s most prominent Canadian, classically trained singers was Juliette Gauthier de la Verendrye2 (1888-1972). Born in Ottawa, Juliette Gauthier attended McGill University, studied music in Europe, and made her debut with the Boston Opera in the United States. The younger sister of the singer Eva Gauthier,3 Juliette Gauthier made her professional career performing French, Inuit, and Native music. -

Proquest Dissertations

Singing to Remember, Singing to Heal: Ts'msyen Music in Public Schools Anne B. Hill B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 1999 A.R.C.T., Royal Conservatory of Music, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Master of Arts In Interdisciplinary Studies The University of Northern British Columbia April 2009 © Anne B. Hill, 2009 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48789-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48789-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

First Nations Pronunciations

A Basic Guide to Names* Listed below are the First Nations Peoples as they are generally known today with a phonetic guide to common pronunciation. Also included here are names formerly given these groups, and the language families to which they belong. People Pronunciation Have Been Called Language Family Haida Hydah Haida Haida Ktunaxa Tun-ah-hah Kootenay Ktunaxa Tsimshian Sim-she-an Tsimshian Tsimshian Gitxsan Git-k-san Tsimshian Tsimshian Nisga'a Nis-gaa Tsimshian Tsimshian Haisla Hyzlah Kitimat Wakashan Heiltsuk Hel-sic Bella Bella Wakashan Oweekeno O-wik-en-o Kwakiutl Wakashan Kwakwaka'wakw Kwak-wak-ya-wak Kwakiutl Wakashan Nuu-chah-nulth New-chan-luth Nootka Wakashan Tsilhqot'in Chil-co-teen Chilcotin Athapaskan Dakelh Ka-kelh Carrier Athapaskan Wet'suwet'en Wet-so-wet-en Carrier Athapaskan Sekani Sik-an-ee Sekani Athapaskan Dunne-za De-ney-za Beaver Athapaskan Dene-thah De-ney-ta Slave(y) Athapaskan Tahltan Tall-ten Tahltan Athapaskan Kaska Kas-ka Kaska Athapaskan Tagish Ta-gish Tagish Athapaskan Tutchone Tuchon-ee Tuchone Athapaskan Nuxalk Nu-halk Bella Coola Coast Salish Coast Salish** Coast Salish Coast Salish Stl'atl'imc Stat-liem Lillooet Interior Salish Nlaka'pamux Ing-khla-kap-muh Thompson/Couteau Interior Salish Okanagan O-kan-a-gan Okanagan Interior Salish Secwepemc She-whep-m Shuswap Interior Salish Tlingit Kling-kit Tlingit Tlingit *Adapted from Cheryl Coull's "A Traveller's Guide to Aboriginal B.C." with permission of the publisher, Whitecap Books ** Although Coast Salish is not the traditional First Nations name for the people occupying this region, this term is used to encompass a number of First Nations Peoples including Klahoose, Homalco, Sliammon, Sechelth, Squamish, Halq'emeylem, Ostlq'emeylem, Hul'qumi'num, Pentlatch, Straits. -

The Pacific Historian, Volume 30, Number 1 (1986)

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons The aP cific iH storian Western Americana 1986 The aP cific iH storian, Volume 30, Number 1 (1986) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pac-historian Recommended Citation "The aP cific iH storian, Volume 30, Number 1 (1986)" (1986). The Pacific isH torian. 116. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pac-historian/116 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Americana at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP cific Historian by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Native Missionaries of the North Pacific Coast Philip McKay and Others E. Palmer Patterson Indian: A History Since 1500 (1972) and Mis sion on the Nass: The Evangelization of the Nishga (1860-1890) (1982). His current re E. Palmer Patterson is Associate Professor search is on the history of the Nishga Indi of History at the University of Waterloo, ans of British Columbia in contact with Ontario, Canada. Among his works on Europeans during the second half of the Canadian native peoples are The Canadian nineteenth century. White missionaries and their native converts. N WRITING THE HISTORY of nineteenth sion is seen as an example of European or Euro century Christian missions the tendency has American/Euro-Canadian cultural expansion and Ibeen to deal primarily with the European and its techniques of dissemination. However, native Euro-American or Euro-Canadian missionarie·s cultures have not always been destroyed, though and their exploits- as adventure, devotion , sac they have often been drastically altered . -

The Cult of the Folk: Ideas and Strategies After Ernest Gagnon Gordon E

Document generated on 10/01/2021 7:19 a.m. Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes The Cult of the Folk: Ideas and Strategies after Ernest Gagnon Gordon E. Smith Canadian Perspectives in Ethnomusicology Article abstract Perspectives canadiennes en ethnomusicologie In this paper I discuss ideas of collectors (Édouard-Zotique Massicotte and Volume 19, Number 2, 1999 Marius Barbeau) vis-à-vis the song collection of Ernest Gagnon. The Chansons populaires repertoire is viewed in different ways by Gagnon's successors as URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014443ar historically significant and/or insignificant, and/or an exhaustive, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1014443ar representative "canon" of songs. Approaches to fieldwork, transcription, and the "selection" of repertoire in these collectors' works are also studied. The second part of the paper sets up a critical frame of reference for these See table of contents strategies based on current literature (e.g., Philip Bohlman, Ian MacKay). Within this discussion, Gagnon's nineteenth-century ideology of "le peuple" is considered alongside the preservationist "cult of the folk" inspiration of his Publisher(s) successors. Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (print) 2291-2436 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Smith, G. E. (1999). The Cult of the Folk: Ideas and Strategies after Ernest Gagnon. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 19(2), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014443ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique This document is protected by copyright law. -

Boas, Hunt, and the Ethnographic Silencing of First Nations Women

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Anthropology Papers Department of Anthropology 2014 My Sisters Will Not Speak: Boas, Hunt, and the Ethnographic Silencing of First Nations Women Margaret Bruchac University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Bruchac, M. (2014). My Sisters Will Not Speak: Boas, Hunt, and the Ethnographic Silencing of First Nations Women. Curator: The Museum Journal, 57 (2), 153-171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12058 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/170 For more information, please contact [email protected]. My Sisters Will Not Speak: Boas, Hunt, and the Ethnographic Silencing of First Nations Women Abstract First Nations women were instrumental to the collection of Northwest Coast Indigenous culture, yet their voices are nearly invisible in the published record. The contributions of George Hunt, the Tlingit/British culture broker who collaborated with anthropologist Franz Boas, overshadow the intellectual influence of his mother, Anislaga Mary Ebbetts, his sisters, and particularly his Kwakwaka'wakw wives, Lucy Homikanis and Tsukwani Francine. In his correspondence with Boas, Hunt admitted his dependence upon high-status Indigenous women, and he gave his female relatives visual prominence in film, photographs, and staged performances, but their voices are largely absent from anthropological texts. Hunt faced many unexpected challenges (disease, death, arrest, financial hardship, and the suspicions of his neighbors), yet he consistently placed Boas' demands, perspectives, and editorial choices foremost.