To Appear in Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth Algonquian Conference, Edited by C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

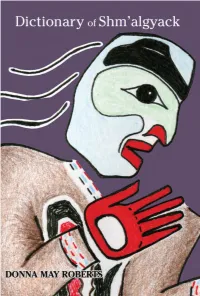

Tsimshian Dictionary

Dictionary of Shm’algyack Donna May Roberts Sealaska Heritage Institute Juneau, Alaska © 2009 by Sealaska Heritage Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 1440401195 EAN-13:9781440401190 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939132 Sealaska Heritage Institute One Sealaska Plaza, Suite 301 Juneau, Alaska 99801 907-463-4844 www.sealaskaheritage.org Printing: Create Space, Scotts Valley, CA, U.S.A. Front cover design: Kathy Dye Front cover artwork: Robert Hoffmann Book design and computational lexicography: Sean M. Burke Copy editing: Suzanne G. Fox, Red Bird Publishing, Inc., Bozeman, MT Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................... 1 Introduction ..................................... 3 Dictionary of Shm’algyack Shm’algyack to English ................ 7 English to Shm’algyack ............... 67 Dictionary of Shm'algyack - 1 aam verb to be fine, good, well PLURAL: am'aam Shm'algyack to ·Aam wila howyu. I’m feeling good. ·Na sheepg nakshu ashda 'guulda English shada dowl mahlda doctor hla aam wila waald gya'win. My wife was sick the other day but the doctor said she’s aab noun my father good now. ·Yagwa goom wunsh aabdu. My aamggashgaawt verb to be of father is hunting for deer. medium size, of a good size aad noun; verb net; to seine ·Aamggashgaawt ga yeeh. The King PLURAL: ga'aad salmon was of a good size. ·Geegsh Dzon shu aad dm hoyt hla aamhalaayt noun headdress, aadmhoant. John bought a new net mask, regalia, shaman’s mask; shaman for fishing. -

Toward the Reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: the Algonquian-Wakashan 110-Item Wordlist

Sergei L. Nikolaev Institute of Slavic studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow/Novosibirsk); [email protected] Toward the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: The Algonquian-Wakashan 110-item wordlist In the third part of my complex study of the historical relations between several language families of North America and the Nivkh language in the Far East, I present an annotated demonstration of the comparative data that was used in the lexicostatistical calculations to determine the branching and approximate glottochronological dating of Proto-Algonquian- Wakashan and its offspring; because of volume considerations, this data could not be in- cluded in the previous two parts of the present work and has to be presented autonomously. Additionally, several new Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan and Proto-Nivkh-Algonquian roots have been set up in this part of study. Lexicostatistical calculations have been conducted for the following languages: the reconstructed Proto-North Wakashan (approximately dated to ca. 800 AD) and modern or historically attested variants of Nootka (Nuuchahnulth), Amur Nivkh, Sakhalin Nivkh, Western Abenaki, Miami-Peoria, Fort Severn Cree, Wiyot, and Yurok. Keywords: Algonquian-Wakashan languages, Nivkh-Algonquian languages, Algic languages, Wakashan languages, Chimakuan-Wakashan languages, Nivkh language, historical phonol- ogy, comparative dictionary, lexicostatistics. The classification and preliminary glottochronological dating of Algonquian-Wakashan currently remain the same as presented in Nikolaev 2015a, Fig. 1 1. That scheme was generated based on the lexicostatistical analysis of 110-item basic word lists2 for one reconstructed (Proto-Northern Wakashan, ca. 800 A.D.) and several modern Algonquian-Wakashan lan- guages, performed with the aid of StarLing software 3. -

Language in the USA

This page intentionally left blank Language in the USA This textbook provides a comprehensive survey of current language issues in the USA. Through a series of specially commissioned chapters by lead- ing scholars, it explores the nature of language variation in the United States and its social, historical, and political significance. Part 1, “American English,” explores the history and distinctiveness of American English, as well as looking at regional and social varieties, African American Vernacular English, and the Dictionary of American Regional English. Part 2, “Other language varieties,” looks at Creole and Native American languages, Spanish, American Sign Language, Asian American varieties, multilingualism, linguistic diversity, and English acquisition. Part 3, “The sociolinguistic situation,” includes chapters on attitudes to language, ideology and prejudice, language and education, adolescent language, slang, Hip Hop Nation Language, the language of cyberspace, doctor–patient communication, language and identity in liter- ature, and how language relates to gender and sexuality. It also explores recent issues such as the Ebonics controversy, the Bilingual Education debate, and the English-Only movement. Clear, accessible, and broad in its coverage, Language in the USA will be welcomed by students across the disciplines of English, Linguistics, Communication Studies, American Studies and Popular Culture, as well as anyone interested more generally in language and related issues. edward finegan is Professor of Linguistics and Law at the Uni- versity of Southern California. He has published articles in a variety of journals, and his previous books include Attitudes toward English Usage (1980), Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register (co-edited with Douglas Biber, 1994), and Language: Its Structure and Use, 4th edn. -

An Early St'at'imcets-Chinook Jargon Bilingual' Text 1 Introduction 1 2 About the Newspaper

"Fox and Cayooty": an early St'at'imcets-Chinook Jargon bilingual' text Henry Davis and David Robertson University of British Columbia and CHINOOK List This paper contains a transliteration (from the original Duployan shorthand) and . translation of an early bilingual St'at'imcets-Chinook Jargon text, with accompanying historical, orthographical and grammatical notes. The story was first published in 1892 in the Kamloops Wawa newspaper by the oblate priest J-M.R. Le Jeune; it thus counts as one of the earliest texts in either language. 1 Introduction 1 It is well known to the student of Salishan languages and cultures that before the time of Franz Boas, extremely few coherent texts, as opposed to relatively numerous fragmentary word-lists, of northwest Native American languages were collected and published. The nascent modern disciplines of anthropology and linguistics demanded such documentation. However, another force besides science played a considerable role in the earliest recordings of indigenous languages of this region: The activities of Christian missionaries, which led to work allowing in some cases (viz. Joseph Giorda, S1's 1871 dictionary of Kalispel) an excellent view of historical stages in the lives of these languages otherwise lost to us.2 An example of the same phenomenon is available to us also in the Kamloops Wawa newspaper published by Oblate father J.-M.R. Le Jeune from 1891 to about 19043, primarily in the Chinook Jargon, of which it is an extensive and often overlooked document. In volume 2, Issue 47 of Kamloops Wawa, dated October 16 [sic], 18924, we find under the English heading "Recreative" the following: Kopa Pavilion ilihi nsaika tlap ukuk hloima syisim kopa Lilwat wawa[:] Fox and Cayooty.~. -

“Viewpoints” on Reconciliation: Indigenous Perspectives for Post-Secondary Education in the Southern Interior of Bc

“VIEWPOINTS” ON RECONCILIATION: INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES FOR POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION IN THE SOUTHERN INTERIOR OF BC 2020 Project Synopsis By Christopher Horsethief, PhD, Dallas Good Water, MA, Harron Hall, BA, Jessica Morin, MA, Michele Morin, BSW, Roy Pogorzelski, MA September 1, 2020 Research Funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Executive Summary This research project synopsis presents diverse Indigenous community perspectives regarding the efforts needed to enable systemic change toward reconciliation within a public post-secondary educational institution in the Southern Interior of British Columbia. The main research question for this project was “How does a community college respectfully engage in reconciliation through education with the First Nations and Métis communities in the traditional territories in which it operates?” This research was realized by a team of six Indigenous researchers, representing distinct Indigenous groups within the region. It offers Indigenous perspectives, insights, and recommendations that can help guide post-secondary education toward systemic change. This research project was Indigenous led within an Indigenous research paradigm and done in collaboration with multiple communities throughout the Southern Interior region of British Columbia. Keywords: Indigenous-led research, Indigenous research methodologies, truth and reconciliation, Indigenous education, decolonization, systemic change, public post- secondary education in BC, Southern Interior of BC ii Acknowledgements This research was made possible through funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada. The important contributions from the Sinixt, Ktunaxa, Syilx, and Métis Elders, Knowledge Keepers, youth, men, and women within this project are essential to restoring important aspects of education that have been largely omitted from the public education system. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians Cynthia J. Manning The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Manning, Cynthia J., "Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5855. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5855 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished m a n u s c r ip t in w h ic h c o p y r ig h t su b s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s c o n ten ts must be a ppro ved BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD L ib r a r y Un iv e r s it y of Montana D a te : 1 9 8 3 AN ETHNOHISTORY OF THE KOOTENAI INDIANS By Cynthia J. Manning B.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1978 Presented in partial fu lfillm en t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Approved by: Chair, Board of Examiners Fan, Graduate Sch __________^ ^ c Z 3 ^ ^ 3 Date UMI Number: EP36656 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Fpcc-Newsletter-Spring-Summer-2014

first peoples’ news spring /summer 2014 first peoples’ cultural council IN THIS ISSUE New Museum Exhibition 2 New Arts Funding from FPCC Available for First Nations Youth SHOWCASING B.C.’S LIVING in B.C. FIRST NATIONS LANGUAGES 3 New Resources Available for First Nations Languages in B.C. Most people are unaware of the variety approaches with contemporary storytell- and richness of languages in this prov- ing. It will make use of audio and visual 4 FirstVoices Resources: Flash Card ince. With 34 Indigenous languages and media, artwork and narrative text in Eng- and Label Maker 61 dialects, B.C. is the most linguistically lish as well as First Nations languages. diverse region in Canada. Most importantly, it will demonstrate 4 Geek Alert! PC Keyboard In an inspiring new partnership, the the diversity and resilience of languages Software Update First Peoples’ Cultural Council (FPCC) in B.C. by showcasing languages by has been working with the Royal BC region as well as individual efforts to 5 Seabird Island Language Nests is Museum to create the innovative rejuvenate languages through hard work Engaging Young Language Learners Our Living Languages exhibition, which and perseverance. will provide an opportunity to celebrate “This is exciting for us and a progressive 6 Mentor-Apprentice Teams Creating these First Nations languages and the move on behalf of the Royal BC Museum,” a New Generation of Speakers people who are working to preserve says FPCC Chair Lorna Williams. “The and revitalize them. museum is a wonderful venue in which to 8 In Conversation with AADA Recipient The exhibition will fuse traditional share the stories and perspectives of First Kevin Loring Continued next page… 9 Upgrades to the FirstVoices Language Tutor Now Available to Communities 10 Community Success Story: SECWEPEMCTSÍN Language Tutor Lessons 11 FirstVoices Coordinator Peter Brand Retires…Or Does He? Our Living Languages: First Peoples' Voices in B.C. -

Lillooet Between Sechelt and Shuswap Jan P. Van Eijk First

Lillooet between Sechelt and Shuswap Jan P. van Eijk First Nations University of Canada Although most details of the grammatical and lexical structure of Lillooet put this language firmly within the Interior branch of the Salish language family, Lillooet also shares some features with the Coast or Central branch. In this paper we describe some of the similarities between Lillooet and one of its closest Interior relatives, viz., Shuswap, and we also note some similarities be tween Lillooet and Sechelt, one of Lillooet' s western neighbours but belonging to the Coast branch. Particular attention is paid to some obvious loans between Lillooet and Sechelt. 1 Introduction Lillooet belongs with Shuswap to the Interior branch of the Salish language family, while Sechelt belongs to the Coast or Central branch. In what follows we describe the similarities and differences between Lillooet and both Shuswap and Sechelt, under the following headings: Phonology (section 2), Morphology (3), Lexicon (4), and Lillooet-Sechelt borrowings (5). Conclusions are given in 6. I omit a comparison between the syntactic patterns of these three languages, since my information on Sechelt syntax is limited to a brief text (Timmers 1974), and Beaumont 1985 is currently unavailable to me. Although borrowings between Lillooet and Shuswap have obviously taken place, many of these will be impossible to trace due to the close over-all resemblance between these two languages. Shuswap data are mainly drawn from the western dialects, as described in Kuipers 1974 and 1975. (For a description of the eastern dialects I refer to Kuipers 1989.) Lillooet data are from Van Eijk 1997, while Sechelt data are from Timmers 1973, 1974, 1977. -

Published in Papers of the Twenty-Third Algonquian Conference, 1992, Edited by William Cowan

Published in Papers of the Twenty-Third Algonquian Conference, 1992, edited by William Cowan. Ottawa: Carleton University, pp. 119-163 A Comparison of the Obviation Systems of Kutenai and Algonquian Matthew S. Dryer SUNY at Buffalo 1. Introduction In recent years, the term ‘obviation’ has been applied to phenomena in a variety of languages on the basis of perceived similarity to the phenomenon in Algonquian languages to which, I assume, the term was originally applied. An example of a descriptive use of the term occurs in Dayley (1989: 136), who applies the terms ‘obviative’ and ‘proximate’ to two categories of demonstratives in Tümpisa Shoshone, the obviative category being used to introduce new information or to reference given participants which are nontopics, the proximate category for topics. But unlike the obviative and proximate categories of Algonquian languages, the Shoshone categories for which Dayley uses the terms are categories only of a class of words he calls ‘demonstratives’, and are not inflectional categories of nouns or verbs. Similarly, Simpson and Bresnan (1983) use the term ‘obviation’ to refer to a system in Warlpiri in which certain nonfinite verbs occur in forms that indicate that their subjects are nonsubjects in the matrix clause. These phenomena in non-Algonquian languages to which the term ‘obviation’ has been applied may bear some remote resemblance to the Algonquian phenomenon, but I suspect that most Algonquianists examining them would conclude that the resemblance is at best a remote one. The purpose of this paper is to describe an obviation system in Kutenai, a language isolate of southeastern British Columbia and adjacent areas of Idaho and Montana, and to compare it to the obviation system of Algonquian languages. -

Growing up Indian: an Emic Perspective

GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTIVE By GEORGE BUNDY WASSON, JR. A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy june 2001 ii "Growing Up Indian: An Ernie Perspective," a dissertation prepared by George B. Wasson, Jr. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. This dissertation is approved and accepted by: Committee in charge: Dr. jon M. Erlandson, Chair Dr. C. Melvin Aikens Dr. Madonna L. Moss Dr. Rennard Strickland (outside member) Dr. Barre Toelken Accepted by: ------------------------------�------------------ Dean of the Graduate School iii Copyright 2001 George B. Wasson, Jr. iv An Abstract of the Dissertation of George Bundy Wasson, Jr. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology to be taken June 2001 Title: GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTN E Approved: My dissertation, GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTN E describes the historical and contemporary experiences of the Coquille Indian Tribe and their close neighbors (as manifested in my own family), in relation to their shared cultures, languages, and spiritual practices. I relate various tribal reactions to the tragedy of cultural genocide as experienced by those indigenous groups within the "Black Hole" of Southwest Oregon. My desire is to provide an "inside" (ernie) perspective on the history and cultural changes of Southwest Oregon. I explain Native responses to living primarily in a non-Indian world, after the nearly total loss of aboriginal Coquelle culture and tribal identity through v decimation by disease, warfare, extermination, and cultural genocide through the educational policies of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. -

Reconstructing Proto-Sahaptian Sounds

Reconstructing Proto-Sahaptian Sounds Noel Rude Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Sahaptin and the mutually unintelligible Nez Perce comprise the Sahaptian language family. This paper attempts to reconstruct the sound system of the parent language of that family. There is little dialect variation in the available data for Nez Perce, whereas Sahaptin divides into three definable dialect clusters: Columbia River (Umatilla, Tenino, Celilo, etc.); Northwest (Klickitat, Upper Cowlitz, Yakima, etc.); Northeast (Priest Rapids, Walla Walla, Palouse, etc.). Various features distinguish the dialects, e.g., long vowels derived from certain VCV sequences are more common in the Northern dialects and in Nez Perce, the Northeast dialects and Nez Perce are more likely to preserve the glottal stop, and the palatalization of *k is most extensive in the Columbia River dialects. The reconstructions proposed here are, as always, more or less tentative. Unless otherwise indicated the examples labeled Sahaptin (S) are from Umatilla.1 Figure 1. The Sahaptian language family Proto-Sahaptian Nez Perce Sahaptin Columbia River Northern Northwest Northeast 1 For the connection between Sahaptin and Nez Perce, see Aoki (1962), Rigsby (1965), Rigsby and Silverstein (1969), and Rude (1996, 2006). For the relationship with Plateau Penutian, see Aoki (1963), Rude (1987), and Pharis (2006). For a possible relationship within the broader Penutian macro-family, see DeLancey & Golla (1979) and Mithun (1999), also Rude (2000) for a possible connection with Uto-Aztecan. For Sahaptin grammars, see Jacobs (1931), Millstein (ca. 1990a), Rigsby and Rude (1996), Rude (2009), and for published NW Sahaptin texts, see Jacobs (1929, 1934, 1937). Beavert and Hargus (2010) provide a dictionary of Yakima Sahaptin, Millstein (ca.