Heichler, Lucian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mautner, Karl.Toc.Pdf

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project KARL F. MAUTNER Interviewed by: Thomas J. Dunnigan Initial interview date: May 12, 1993 opyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Austria Austrian Army 1 35-1 36 Emigrated to US 1 40 US Army, World War II Berlin 1 45-1 5, Divided Berlin Soviet Blockade and US Airlift .urrency Reform- Westmark Elections, 01 4,1 Federal Basic 2a3 and Berlin East vs. West Berlin Revolt in East Berlin With Brandt and Other Personalities Bureau of .ultural Affairs - State Department 1 5,-1 61 European E5change Program Officer Berlin Task Force 1 61-1 65 Berlin Wall 6ice President 7ohnson8s visit to Berlin 9hartoum, Sudan 1 63-1 65 .hief of political Section Sudan8s North-South Rivalry .oup d8etat Department of State, Detailed to NASA 1 65 Negotiating Facilities Abroad Retirement 1 General .omments of .areer INTERVIEW %: Karl, my first (uestion to you is, give me your background. I understand that you were born in Austria and that you were engaged in what I would call political work from your early days and that you were active in opposition to the Na,is. ould you tell us something about that- MAUTNER: Well, that is an oversimplification. I 3as born on the 1st of February 1 15 in 6ienna and 3orked there, 3ent to school there, 3as a very poor student, and joined the Austrian army in 1 35 for a year. In 1 36 I got a job as accountant in a printing firm. I certainly couldn8t call myself an active opposition participant after the Anschluss. -

Ciprnet Deliverable D6.3

FP7 Grant Agreement N° 312450 Project type: Network of Excellence (NoE) Thematic Priority: FP7 Cooperation, Theme 10: Security Start date of project: March 1, 2013 Duration: 48 months Due date of deliverable: 31/08/2015 Actual submission date: 31/08/2015 Revision: Version 1 Fraunhofer Institute for Intelligent Analysis and Information Systems (Fraunhofer) Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme (2007–2013) Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Author(s) Erich Rome, Josef Börding Stefan Rilling, Norman Voß (Fraunhofer) Contributor(s) Betim Sojeva, Rainer Worst, Jingquan Xie, Thomas Doll, (Fraunhofer) Andreas Burzel (Deltares), Nikolas Flourentzou (UCY), Rafal Kozik (UTP) Security Assessment D. Sérafin (CEA) Approval Date 31.08.2015 Remarks No security issues The project CIPRNet has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Pro- gramme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 312450. The contents of this publication do not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the authors. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. -

Yale University Library Digital Repository Contact Information

Yale University Library Digital Repository Collection Name: Henry A. Kissinger papers, part II Series Title: Series I. Early Career and Harvard University Box: 9 Folder: 21 Folder Title: Brandt, Willy Persistent URL: http://yul-fi-prd1.library.yale.internal/catalog/digcoll:554986 Repository: Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library Contact Information Phone: (203) 432-1735 Email: [email protected] Mail: Manuscripts and Archives Sterling Memorial Library Sterling Memorial Library P.O. Box 208240 New Haven, CT 06520 Your use of Yale University Library Digital Repository indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use http://guides.library.yale.edu/about/policies/copyright Find additional works at: http://yul-fi-prd1.library.yale.internal February 4, 1959 Mayor Willy Brandt Berlin ;ermany Dear Mayor Brandt: I returned to the United States a few days ago, and want to lose no time in thanking you for the extraordinary und interesting experience afforded to me in Berlin. It was of course a pleasure to have the chance to meet you. It seems to me that the courage and matter-of-factne$s of the Berliners should be an inspiration for the rest of the free world, and in this respect Berlin may well be the conscience of all of us. I want you to know that whatever I can do within my limited iowers here will U.) done. All good wishes and kind regards. ,Ancerely yours, iienryrt. Kissinger 2ZRI .4 xlsaldel Ibnala x1114; xamtneL abasme noyAM 11590 eydeb wel a ap.ts.ta be4inU ea pi benlidvi I ea lol pox anlAnadI n1 salt on pool od. -

The Importance of Osthandel: West German-Soviet Trade and the End of the Cold War, 1969-1991

The Importance of Osthandel: West German-Soviet Trade and the End of the Cold War, 1969-1991 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Charles William Carter, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Carole Fink, Advisor Professor Mansel Blackford Professor Peter Hahn Copyright by Charles William Carter 2012 Abstract Although the 1970s was the era of U.S.-Soviet détente, the decade also saw West Germany implement its own form of détente: Ostpolitik. Trade with the Soviet Union (Osthandel) was a major feature of Ostpolitik. Osthandel, whose main feature was the development of the Soviet energy-export infrastructure, was part of a broader West German effort aimed at promoting intimate interaction with the Soviets in order to reduce tension and resolve outstanding Cold War issues. Thanks to Osthandel, West Germany became the USSR’s most important capitalist trading partner, and several oil and natural gas pipelines came into existence because of the work of such firms as Mannesmann and Thyssen. At the same time, Moscow’s growing emphasis on developing energy for exports was not a prudent move. A lack of economic diversification resulted, a development that helped devastate the USSR’s economy after the oil price collapse of 1986 and, in the process, destabilize the communist bloc. Against this backdrop, the goals of some West German Ostpolitik advocates—especially German reunification and a peaceful resolution to the Cold War—occurred. ii Dedication Dedicated to my father, Charles William Carter iii Acknowledgements This project has been several years in the making, and many individuals have contributed to its completion. -

Yale University Library Digital Repository Contact Information

Yale University Library Digital Repository Collection Name: Henry A. Kissinger papers, part II Series Title: Series I. Early Career and Harvard University Box: 9 Folder: 21 Folder Title: Brandt, Willy Persistent URL: http://yul-fi-uat1.library.yale.internal/catalog/digcoll:554986 Repository: Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library Contact Information Phone: (203) 432-1735 Email: [email protected] Mail: Manuscripts and Archives Sterling Memorial Library Sterling Memorial Library P.O. Box 208240 New Haven, CT 06520 Your use of Yale University Library Digital Repository indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use http://guides.library.yale.edu/about/policies/copyright Find additional works at: http://yul-fi-uat1.library.yale.internal February 4, 1959 Mayor Willy Brandt Berlin ;ermany Dear Mayor Brandt: I returned to the United States a few days ago, and want to lose no time in thanking you for the extraordinary und interesting experience afforded to me in Berlin. It was of course a pleasure to have the chance to meet you. It seems to me that the courage and matter-of-factne$s of the Berliners should be an inspiration for the rest of the free world, and in this respect Berlin may well be the conscience of all of us. I want you to know that whatever I can do within my limited iowers here will U.) done. All good wishes and kind regards. ,Ancerely yours, iienryrt. Kissinger 2ZRI .4 xlsaldel Ibnala x1114; xamtneL abasme noyAM 11590 eydeb wel a ap.ts.ta be4inU ea pi benlidvi I ea lol pox anlAnadI n1 salt on pool od. -

Address Given by Willy Brandt to the Bundestag on the Building of the Berlin Wall (Bonn, 18 August 1961)

Address given by Willy Brandt to the Bundestag on the building of the Berlin Wall (Bonn, 18 August 1961) Caption: On 18 November 1961, Willy Brandt, Governing Mayor of Berlin, addresses the Bundestag and denounces the building of the Berlin Wall and the violation by the Soviet Union of the city’s four-power status. Source: Verhandlungen des deutschen Bundestages. 3. Wahlperiode. 167. Sitzung vom 18. August 1961. Stenographische Berichte. Hrsg. Deutscher Bundestag und Bundesrat. 1961, Nr. 49. Bonn. "Rede von Willy Brandt", p. 9773-9777. Copyright: (c) Translation CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/address_given_by_willy_brandt_to_the_bundestag_on_the _building_of_the_berlin_wall_bonn_18_august_1961-en-8c749afa-e8ac-4840-ac25- 3568a2d1a4d9.html Last updated: 05/07/2016 1/7 Address given by Willy Brandt to the Bundestag on the building of the Berlin Wall (Bonn, 18 August 1961) Brandt, Governing Mayor of Berlin (greeted with applause by the SPD): Mr Speaker, ladies and gentlemen, it is fairly rare for a component part of the Bundesrat to address this House. The fact that I appear before you today on behalf of the State of Berlin is a reflection of the extraordinary position in which we now find ourselves. It is not just Berlin that concerns us here, it is the cold menace which has settled over the other part of Germany and the Eastern sector of my city, as it once did over Hungary: you have all seen the pictures of the barbed wire, concrete posts and concrete walls, the tanks, the tank traps and the troops in full battle gear. -

Deutscheallgemeınezeitung

Общая Немецкая Газета DeutscheAllgemeıneZseit 1966eitung DIE DEUTSCH-RUSSISCHE WOCHENZEITUNG IN ZENTRALASIEN 07. bis 13. August 2009 Nr. 31/8391 Glühbirne Schritt für Schritt schaff t die Europäische Union die klassi- schen Glühbirnen ab – Desi- gner protestieren. 5 Hauptstadt Bild: http://idt-2009.de/ Berlin, die Weltmetropole der „Wenn die Deutschen sich nicht mehr für ihre Sprache engagieren, wird die Zahl der Deutschsprachigen weiter zurückgehen“, darin Gefühlsschwankungen – eine waren sich die Deutschlehrer aus 116 Ländern in Jena einig. Liebeserklärung von Autorin SPRACHPOLITIK Merle Hilbk. 9 DEUTSCHLEHRER FÜR MEHR DEUTSCH IM AUSLAND Sechs Tage lang diskutierten in der ersten Augustwoche rund 3.000 Deutschlehrer aus 116 Ländern über die Entwicklung der deutschen Sprache und die optimale Vermittlung von Deutsch als Fremdsprache. Die soll von deutschen Politikern im Ausland häufi ger gebraucht werden, fordern die Pädagogen. Der internationale Verband der Deutsch- Politiker und Wirtschaftsführer hätten dabei Sprachen. Rund 17 Millionen Ausländer lehrer hat deutsche Politiker aufgefordert, eine Vorbildfunktion – und oft sei das Deut- lernen Deutsch. Allerdings sei deren Zahl im Ausland öfter Deutsch zu sprechen. sche im Ausland die bessere Wahl: „Oft leiden in den vergangenen Jahren stark zurück- ЯЗЫК „Wenn die Deutschen bei offi ziellen Anläs- die Tiefe und die Klarheit der Gedanken, wenn gegangen. Немецкая республиканская sen im Ausland nicht ihre Muttersprache jemand versucht, die englische Sprache zu Besonders in Osteuropa, wo Deutsch benutzen, schaden sie der deutschen benutzen – ohne es zu können.“ lange stärker als Englisch gewesen sei, газета предлагает своим Sprache im Wettbewerb der Sprachen werde die deutsche Sprache zuneh- читателям возможность in einer globalen und mehrsprachigen Schwund in Osteuropa am größten mend verdrängt, sagte Hanuljaková. -

Und Ostpolitik Der Ersten Großen Koalition in Der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (1966-1969)

Die Deutschland- und Ostpolitik der ersten Großen Koalition in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (1966-1969) Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Martin Winkels aus Erkelenz Bonn 2009 2 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät Der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission Vorsitzender: PD Dr. Volker Kronenberg Betreuer: Hon. Prof. Dr. Michael Schneider Gutacher: Prof. Dr. Tilman Mayer Weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied: Hon. Prof. Dr. Gerd Langguth Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 11.11.2009 Diese Dissertation ist auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/diss_online elektonisch publiziert 3 Danksagung: Ich danke Herrn Professor Dr. Michael Schneider für die ausgezeichnete Betreuung dieser Arbeit und für die sehr konstruktiven Ratschläge und Anregungen im Ent- stehungsprozess. Ebenso danke ich Herrn Professor Dr. Tilman Mayer sehr dafür, dass er als Gutachter zur Verfügung gestanden hat. Mein Dank gilt auch den beiden anderen Mitgliedern der Prüfungskommission, Herrn PD Dr. Volker Kronenberg und Herrn Prof. Dr. Gerd Langguth. 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 7 1. Der Beginn der Außenpolitik der Bundesrepublik Deutschland ab 1949 und 23 die deutsche Frage 1.1. Die Deutschland- und Ostpolitik der Bundesregierung Adenauer zwischen 25 Westintegration und Kaltem Krieg (1949-1963) 1.2. Die Deutschland- und Ostpolitik unter Kanzler Erhard: Politik der 31 Bewegung (1963-1966) 1.3. Die deutschland- und ostpolitischen Gegenentwürfe der SPD im Span- 40 nungsfeld des Baus der Berliner Mauer: “Wandel durch Annäherung“ 2. Die Bildung der Großen Koalition: Ein Bündnis auf Zeit 50 2.1. Die unterschiedlichen Politiker-Biographien in der Großen Koalition im 62 Hinblick auf das Dritte Reich 2.2. -

Implementation Plan

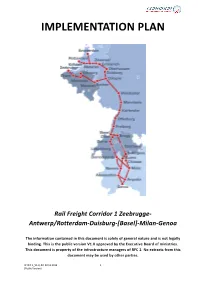

IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Rail Freight Corridor 1 Zeebrugge- Antwerp/Rotterdam-Duisburg-[Basel]-Milan-Genoa The information contained in this document is solely of general nature and is not legally binding. This is the public version V1.0 approved by the Executive Board of ministries. This document is property of the infrastructure managers of RFC 1. No extracts from this document may be used by other parties. IP RFC 1_V1.0, dd. 03.12.2013 1 (Public Version) Implementation Plan RFC 1 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 8 2 CORRIDOR DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 CORRIDOR LINES ............................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.1 Routing ........................................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2 Traffic Demand ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 2.1.3 Bottlenecks ................................................................................................................................................................... 18 2.1.4 Available Capacity ........................................................................................................................................................ -

UC Berkeley Working Papers

UC Berkeley Working Papers Title The demand for referendums in West Germany : bringing the people back in? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8dk5p1fk Author Luthardt, Wolfgang Publication Date 1990 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California s/ A/^5S no. •7// /? THE DEMAND FOR REFERENDDMS IN WEST 6ERMANT "BRINGING THE PEOPLE BACK IN?" y Wolfgang Luthardt 7 Free University of Berlin Department of Political Science Ihnestrasse 21 D-1000 Berlin 33 Working Paper 90-21 mmm OF SOVeRNMgNTAl STUDIES LIBRARY Jl L 131990 UNIVERSIY OF CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF GOVERNMENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY THE DEMAND FOR REFERENDDMS IN WEST GERMANY: "BRINGING THE PEOPLE BACK IN?" Wolfgang Luthardt Free University of Berlin Department of Political Science Ihnestrasse 21 D-1000 Berlin 33 Current U.S. Address: Harvard University Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies 27 Kirkland Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Working Paper 90-21 Working Papers published by the Institute of Governmental Studies provide quick dissemination of draft reports and papers, preliminary analyses, and papers with a limited audience. The objective is to assist authors in refining their ideas by circulating research results and to stimulate discussion about public policy. Working Papers are reproduced unedited directly from the author's pages. II. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM The demand for "more direct democracy"^ in the form of initiatives and referendums has, since the early 1980s, again emerged as an important institutional and political theme in public debate in West Germany^. With the entrance of this theme intomany arena of discussion, the advocates of such tactics have widely varying aims. -

Overseas Railways July 2019

The R.C.T.S. is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation registered with The Charities Commission Registered No. 1169995. THE RAILWAY CORRESPONDENCE AND TRAVEL SOCIETY PHOTOGRAPHIC LIST LIST 8 - OVERSEAS RAILWAYS JULY 2019 The R.C.T.S. is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation registered with The Charities Commission Registered No. 1169995. www.rcts.org.uk VAT REGISTERED No. 197 3433 35 R.C.T.S. PHOTOGRAPHS – ORDERING INFORMATION The Society has a collection of images dating from pre-war up to the present day. The images, which are mainly the work of late members, are arranged in in fourteen lists shown below. The full set of lists covers upwards of 46,900 images. They are : List 1A Steam locomotives (BR & Miscellaneous Companies) List 1B Steam locomotives (GWR & Constituent Companies) List 1C Steam locomotives (LMS & Constituent Companies) List 1D Steam locomotives (LNER & Constituent Companies) List 1E Steam locomotives (SR & Constituent Companies) List 2 Diesel locomotives, DMUs & Gas Turbine Locomotives List 3 Electric Locomotives, EMUs, Trams & Trolleybuses List 4 Coaching stock List 5 Rolling stock (other than coaches) List 6 Buildings & Infrastructure (including signalling) List 7 Industrial Railways List 8 Overseas Railways & Trams List 9 Miscellaneous Subjects (including Railway Coats of Arms) List 10 Reserve List (Including unidentified images) LISTS Lists may be downloaded from the website http://www.rcts.org.uk/features/archive/. PRICING AND ORDERING INFORMATION Prints and images are now produced by ZenFolio via the website. Refer to the website (http://www.rcts.org.uk/features/archive/) for current prices and information. NOTES ON THE LISTS 1. Colour photographs are identified by a ‘C’ after the reference number. -

National NOTE 132P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 275 570 SO 017 314 AUTHOR Glasrud, Clarence A., Ed. TITLE A Special Relationship: Germany and Minnesota, 1945-1985=Brucken Uber Grenzen: Minnesota und Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1945-1985. INSTITUTION Concordia Coll., Moorhead, Minn. SPONS AGENCY Minnesota Humanities Commission, St. Paul.; National Endowment Zor the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 83 NOTE 132p.; Papers presented at a conference entitled "A Heritage Fulfilled: German Americans" (Minneapolis, MN, April 22, 1982). Some photographs may not reproduce well. AVAILABLE FROM International Language Villages, Concordia College, Moorhead, MN 56560 (write for price). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021)-- Historical Materials (060) -- Reports- General (140) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Ethnic Groups; *Ethnicity; Foreign Countries; *Global Approach; Group Unity; Higher Education; *Intercultural Programs; *International Cooperation; *International Relations; International Trade; Resource Materials; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Minnesota; *West Germaay ABSTRACT This collection of conference papers describes the post-World War II relationship between Germany and Minnesota. The relationship with the Federal Republic of West Germany is emphasized but East Germany is not ignored. The papers include: "Current Issues in German-American Relations" (P. Hermes); "The Cult of Talent and Genius: A German Specialty" (F. R. Stern with R. W. Franklin); "West Germany: Economic Power--Political Power" (L. J. Rippley); "The Image of the German in Contemporary Minnesota" (G. H. Weiss); "Cultural Exchange, Germany-Minnesota: A Case Study in Education" (N. Benzel); "The German Theological and Liturgical Influence in Minnesota: St. John's Abbey and the Liturgical Revival" (R. W. Franklin); "The German Impact on Modernism in Art" (M.