Searching for the Semantic Boundaries of the Japanese Colour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I Have Been

Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I have been unconsciously entangled in a historical process of the making of modern Buddhism. There was a Chinese temple beside my house in Penang, Malaysia. The main deity was likely a deified imperial court officer, though no historical record documented his origin. A mosque serenely resided along the main street approximately 50 meters from my house. At the end of the street was a Hindu temple decorated with colorful statues. Less than five minutes’ walk from my house was a Buddhist association in a two-storey terrace. During my childhood, the Chinese temple was a playground. My friends and I respected the deities worshipped there but sometimes innocently stole sweets and fruits donated by worshippers as offerings. Each year, three major religious events were organized by the temple committee: the end of the first lunar month marked the spring celebration of a deity in the temple; the seventh lunar month was the Hungry Ghost Festival; and the eighth month honored, She Fu Da Ren, the temple deity’s birthday. The temple was busy throughout the year. Neighbors gathered there to chat about national politics and local gossip. The traditional Chinese temple was thus deeply rooted in the community. In terms of religious intimacy with different nearby temples, the Chinese temple ranked first, followed by the Hindu temple and finally, the mosque, which had a psychological distant demarcated by racial boundaries. I accompanied my mother several times to the Hindu temple. Once, I asked her why she prayed to a Hindu deity. -

From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature

From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature Nan Ma Hartmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Nan Ma Hartmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature Nan Ma Hartmann This dissertation examines the reception of Chinese language and literature during Tokugawa period Japan, highlighting the importation of vernacular Chinese, the transformation of literary styles, and the translation of narrative fiction. By analyzing the social and linguistic influences of the reception and adaptation of Chinese vernacular fiction, I hope to improve our understanding of genre development and linguistic diversification in early modern Japanese literature. This dissertation historically and linguistically contextualizes the vernacularization movements and adaptations of Chinese texts in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries, showing how literary importation and localization were essential stimulants and also a paradigmatic shift that generated new platforms for Japanese literature. Chapter 1 places the early introduction of vernacular Chinese language in its social and cultural contexts, focusing on its route of propagation from the Nagasaki translator community to literati and scholars in Edo, and its elevation from a utilitarian language to an object of literary and political interest. Central figures include Okajima Kazan (1674-1728) and Ogyû Sorai (1666-1728). Chapter 2 continues the discussion of the popularization of vernacular Chinese among elite intellectuals, represented by the Ken’en School of scholars and their Chinese study group, “the Translation Society.” This chapter discusses the methodology of the study of Chinese by surveying a number of primers and dictionaries compiled for reading vernacular Chinese and comparing such material with methodologies for reading classical Chinese. -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15Th ICAL 2021 WELCOME

15TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AUSTRONESIAN LINGUISTICS BOOK OF ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15th ICAL 2021 WELCOME The Austronesian languages are a family of languages widely dispersed throughout the islands of The name Austronesian comes from Latin auster ICAL The 15-ICAL wan, Philippines 15th ICAL 2021 ORGANIZERS Department of Asian Studies Sinophone Borderlands CONTACTS: [email protected] [email protected] 15th ICAL 2021 PROGRAMME Monday, June 28 8:30–9:00 WELCOME 9:00–10:00 EARLY CAREER PLENARY | Victoria Chen et al | CHANNEL 1 Is Malayo-Polynesian a primary branch of Austronesian? A view from morphosyntax 10:00–10:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL 2 S2: S1: 10:30-11:00 Owen Edwards and Charles Grimes Yoshimi Miyake A preliminary description of Belitung Malay languages of eastern Indonesia and Timor-Leste Atsuko Kanda Utsumi and Sri Budi Lestari 11:00-11:30 Luis Ximenes Santos Language Use and Language Attitude of Kemak dialects in Timor-Leste Ethnic groups in Indonesia 11:30-11:30 Yunus Sulistyono Kristina Gallego Linking oral history and historical linguistics: Reconstructing population dynamics, The case of Alorese in east Indonesia agentivity, and dominance: 150 years of language contact and change in Babuyan Claro, Philippines 12:00–12:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 12:30–13:30 PLENARY | Olinda Lucas and Catharina Williams-van Klinken | CHANNEL 1 Modern poetry in Tetun Dili CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL -

Hardening Alternation in the Mitsukaido Dialect of Japanese

言語研究(Gengo Kenkyu)134: 85–118(2008) 85 Hardening Alternation in the Mitsukaido Dialect of Japanese Kan Sasaki Sapporo Gakuin University Abstract: Th e Mitsukaido dialect of Japanese has a phenomenon in which a stem-initial fricative turns into a stop (or an aff ricate) when the stem is the second member of a compound. Th is hardening alternation results from opaque interactions among four phonological processes: sequential voicing, debuccaliza- tion (p→h), continuancy neutralization and consonant devoicing. Consonant devoicing counterfeeds sequential voicing and p→h, and counterbleeds continu- ancy neutralization. Classic Optimality Th eory cannot deal with the phonologi- cal opacity behind the hardening alternation. Stratal OT, a weak parallelist OT extension which incorporates level ordering, provides a solution for this phe- nomenon. Strict parallelist extensions such as Sympathy theory and Candidate Chain theory make the wrong prediction for the hardening alternation.* Key words: devoicing, hardening, Optimality Th eory, phonological opacity, Stratal OT 1. Introduction Th e Mitsukaido dialect of Japanese, spoken in the southwestern part of Ibaraki Prefecture, has a mixed phonological system displaying both Tohoku dialect prop- erties, such as intervocalic voicing and consonant devoicing, and southern Kanto dialect properties, such as lack of prenasal consonants. Its mixed nature is also found in morphosyntactic properties like the presence of the dative/allative case particle -sa peculiar to Tohoku dialects and the absence of productive anticausative voice, as in southern Kanto dialects. Due to this mixed character, the Mitsukaido dialect is often referred to as Kanto no Tohoku-hogen ‘Tohoku dialect spoken in Kanto’. Th e phenomenon I analyze in this paper is the hardening alternation exemplifi ed in (1), a phonological alternation derived from the mixed nature of this dialect. -

Swahili-English Dictionary, the First New Lexical Work for English Speakers

S W AHILI-E N GLISH DICTIONARY Charles W. Rechenbach Assisted by Angelica Wanjinu Gesuga Leslie R. Leinone Harold M. Onyango Josiah Florence G. Kuipers Bureau of Special Research in Modern Languages The Catholic University of Americ a Prei Washington. B. C. 20017 1967 INTRODUCTION The compilers of this Swahili-English dictionary, the first new lexical work for English speakers in many years, hope that they are offering to students and translators a more reliable and certainly a more up-to-date working tool than any previously available. They trust that it will prove to be of value to libraries, researchers, scholars, and governmental and commercial agencies alike, whose in- terests and concerns will benefit from a better understanding and closer communication with peoples of Africa. The Swahili language (Kisuiahili) is a Bantu language spoken by perhaps as many as forty mil- lion people throughout a large part of East and Central Africa. It is, however, a native or 'first' lan- guage only in a nnitp restricted area consisting of the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba and the oppo- site coast, roughly from Dar es Salaam to Mombasa, Outside this relatively small territory, elsewhere in Kenya, in Tanzania (formerly Tanganyika), Copyright © 1968 and to a lesser degree in Uganda, in the Republic of the Congo, and in other fringe regions hard to delimit, Swahili is a lingua franca of long standing, a 'second' (or 'third' or 'fourth') language enjoy- ing a reasonably well accepted status as a supra-tribal or supra-regional medium of communication. THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA PRESS, INC. -

Papers in Pidgin and Creole Linguistics No. 5

Papers in pidgin and creole linguistics No.5 Mühlhäusler, P. editor. Papers in Pidgin and Creole Linguistics No. 5. A-91, v + 213 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1998. DOI:10.15144/PL-A91.cover ©1998 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurrn EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), Thomas E. Dutton, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financedlargely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. To date Pacific Linguistics has published over 400 volumes in four series: -Series A: Occasional Papers; collections of shorter papers, usually on a single topic or area. -

Toponymic Guidelines for Map and Other Editors Japan

Contents Page 1. Language 1.1 National language・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・2 1.2 The Japanese language・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・2 1.3 Common alphabet・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 3 1.4 Rules for spelling Japanese geographical names ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・6 1.4.1 Spelling rules for the romanization of Japanese geographical names・・・・6 1.5 Pronunciation of Japanese geographical names・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・7 1.6 Basic knowledge of Japanese geographical names・・・・・・・・・・・・・・8 2. Committee on the standardization and method of the standardization of geographical names 2.1 Committee on the standardization of geographical names・・・・・・・・・・・8 2.2 The method of the standardization of geographical names・・・・・・・・・・8 3. Source materials 3.1 Maps・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・9 3.2 Gazetteers・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・9 4. Glossary of generic terms necessary for the understanding maps of Japan・・・・・9 5. Administrative divisions・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・11 1. Language 1.1 National language Japan is a unilingual country, and has used Japanese as its official language since its beginning. The northern regions of Japan have been inhabited by a small number of Ainu people who in the past had spoken their own language. They had no letters or characters of their own. Now, Ainu people no longer speak in their aboriginal language, however, a trace of the vanished Ainu language survives in geographical names and epics or "Yûkara" which have been handed down in the oral tradition for generations. Many people speak in their own dialects in Japan, but the standard Japanese language is normally used on official occasions. 1.2 The Japanese language The Japanese language has been spoken by Japanese people since ancient times. Historically, the Japanese language has been largely influenced by the Chinese language adapting many of its characters and its vocabulary. -

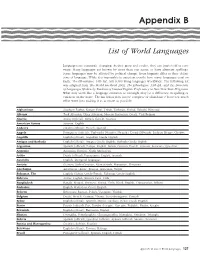

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages

Appendix B bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages Languages are constantly changing. As they grow and evolve, they can branch off or con- verge. Many languages are known by more than one name, or have alternate spellings. Some languages may be affected by political change. Even linguists differ in their defini- tions of language. While it is impossible to ascertain exactly how many languages exist on Earth, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., lists 6,809 living languages worldwide. The following list was adapted from The World Factbook 2002, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., and the Directory of Languages Spoken by Students of Limited English Proficiency in New York State Programs. What may seem like a language omission or oversight may be a difference in spelling or variation on the name. The list below may not be complete or all-inclusive; however, much effort went into making it as accurate as possible. Afghanistan Southern Pashto, Eastern Farsi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Brahui, Balochi, Hazaragi Albania Tosk Albanian, Gheg Albanian, Macedo-Romanian, Greek, Vlax Romani Algeria Arabic (official), French, Kabyle, Chaouia American Samoa Samoan, English Andorra Catalán (official), French, Spanish Angola Portuguese (official), Umbundu, Nyemba, Nyaneka, Loanda-Mbundu, Luchazi, Kongo, Chokwe Anguilla English (official), Anguillan Creole English Antigua and Barbuda English (official), Antigua Creole English, Barbuda Creole English Argentina Spanish (official), Pampa, English, Italian, German, French, Guaraní, Araucano, Quechua Armenia Armenian, Russian, North Azerbaijani -

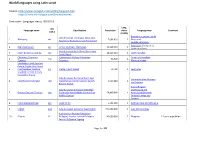

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

English Version

早稲田大学 GLCA/ACM ジャパン・ スタディ・プログラム 春の実習情告書 z 2019 ○年 2020 Japan Study at Waseda University Cultural Internship Program Report Table of Contents Opening Remarks (Sam Pack)………………………………………………… ii CI Site Location Map………………………………………………………… iii Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture……………………………………………… 1 Hakuba, Nagano Prefecture…………………………………………………2 Fujikawaguchiko, Yamanashi Prefecture……………………………………3 Minakami, Gunma Prefecture ……………………………...…………………4 Fukui, Fukui Prefecture ………………………………………………………5 Daito, Osaka Prefecture ….……………………...……………………………7 Iiyama, Nagano Prefecture .…………………………………………………9 Sogenji, Okayama Prefecture ……………………………………………..10 Taku, Saga Prefecture……………………………………………………… 15 Miyazaki, Miyazaki Prefecture ……………………………………………16 Unnan, Shimane Prefecture ………………………………………………18 Mashiko, Tochigi Prefecture ………………………………………………22 Closing Remarks (Michiyo Nagayama)……………………………………25 | i Opening Remarks For more than two decades, the Cultural Internship has been one of the defining features of the Japan Study Program. For one month, students are provided the opportunity to leave the familiar cocoon of Tokyo and to immerse themselves in more remote locations throughout the country. Through varied work assignments, extended home stays, and everyday interactions, they become acquainted with new ways of life. Indeed, the Cultural Internship is a remarkable and unparalleled experience that is not possible to replicate in any other way. On behalf of the Japan Study Program, I wish to extend my heartfelt gratitude to all of our CI partners for inviting our students -

The Liquid and Stem-Final Vowel Alternations of Verbs in Ancient Japanese*

言 語 研 究(Gengo Kenkyu)118(2000),5~27 5 The Liquid and Stem-final Vowel Alternations of Verbs in Ancient Japanese* Teruhiro HAYATA (Daitobunka University) Key words: liquid, verb inflection, vowel alternation, regressive assimilation, Ancient Japanese The aim of this paper is to clarify the phonological motivation for the stem-final /i-u/ and /e-u/ alternations of verbs, as well as properties of liquids in Ancient Japanese. I explore the possibility of a connection between the stem-final vowel alternations in verbs and certain proper- ties of liquid consonants. Present-day Japanese, at least the Tookyoo dialect, does not exhibit stem-final /i-u/ and /e-u/ alternations of verbs. Some modern dialects, e.g., those in Kyuushuu, exhibit alternation only in /e/-stem verbs, but not in /i/-stem verbs. This /e-u/ alternation is a relic of Ancient Japanese. There has been only one liquid phoneme in Japanese throughout its history, whose phonetic realization remains an issue for phonologists. 1. Partial paradigms of Ancient Japanese verbs In Ancient Japanese, verbs are divided into consonant-stem verbs and vowel-stem verbs with or without vowel-alternation. Stem-final sylla- bles of vowel-stem verbs are of three types, namely, /Ci1/, /Ci2/ and * An inaugural lecture given in Japanese at Chiba University on June 17, 2000. The original title was "Phonology of r and 1: especially in Ancient Japanese" 6 TeruhiroHAYATA /Ce2/1). Verbs consisting of a monosyllabic stem in the form /Cil/ exhibit no vowel alternation, and will not be treated in this paper. -

Milli Mála 1-218 6/28/11 1:39 PM Page 281

Milli mála 2011_Milli mála 1-218 6/28/11 1:39 PM Page 281 KaOru uMEZaWa unIVErSITY OF ICELanD Transliterating Icelandic names into Japanese Katakana Words an Exploratory Study 1. Introduction ranscribing sounds of one language into another can be prob - Tlematic, especially with languages that use very different alpha - bets and sound systems, such as Japanese and English, or arabic and English. 1 Japanese uses three orthographic systems concurrent - ly; one of them, katakana , is used primarily for transcribing loan words and foreign names. However, katanaka is a syllabary . T his mirrors the Japanese intuition of the sound-shape of words: in seg - mental phonemic terms, Japanese has phonotactic constraints of an entirely different character from Icelandic ones. This difference forms the background to the discussion in this essay. Thus when foreign names are transliterated into Japanese, the sounds are changed phonologically to fit into the Japanese sound system before being transcribed into katakana .2 The national Language Council of Japan has published a series of guidelines for transcribing loan words, recognising at the same time that a tran - scription which follows the original sound too closely may not be ideal. as the Japanese sound system continues to develop, the set of sounds used to transcribe foreign words may tend either towards simplification or the enrichment of the Japanese sound system 1 Kevin Knight and Jonathan graehl, “Machine Transliteration”, Computational Linguistic 24(4)/1998, pp. 599– 612, here p. 599. 2 石井久雄他、 言葉 に関する 問題集―外来語編― 、東京:文化庁 、1997, pp. 18–19. 石綿敏雄、外来語 の総合的研究、東京:東京堂出版、 2001, p.