Monguor; Sketch Grammar of the Karlong Variety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Festschrift for Robert Blust

Austronesian historical linguistics and culture history: a festschrift for Robert Blust Edited by Alexander Adelaar and Andrew Pawley Pacific Linguistics Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Table of contents Contributors to this volume x Acknowledgements xiii Parti: About Bob 1 Reflections on Bob Blust's career Alexander ADELAAR and Andrew PAWLEY 3 2 Feting Bob's career to date Byron W. BENDER 17 3 Thoughts on learning that Bob Blust has reached festschrift age George W. GRACE 19 4 The publications of Robert A. Blust 23 Part 2: Sound change 5 Structure-preserving sound change: a look at unstressed vowel syncope in Austronesian Juliette BLEVINS 39 6 Irregular sound change and the post-velars in some Malakula languages John LYNCH 57 7 In search of an historical Sea-People Malay dialect with -aba- Waruno MAHDI 73 8 The sounds of Southeast Babar Hein STE1NHAUER 91 9 Motherese and historical implications Shigeru TSUCHIDA 107 10 The Proto Austronesian laryngeal John WOLFF 115 vii Vlll Part 3: Grammatical change and typology 11 The various origins of the passive prefix di- Alexander ADELAAR 129 12 Relative-clause bracketing in Oceanic languages around the Huon Gulf of New Guinea Joel BRADSHAW 143 13 The history of the Tukang Besi pronominals MarkDONOHUE 163 14 Verbal aspect and personal pronouns: the history of aorist markers in north Vanuatu Alexandre FRANCOIS 179 15 Austronesian typology and the nominalist hypothesis Daniel KAUFMAN 197 16 Start and finish: some grammatical changes in Toqabaqita Frantisek -

Inyo National Forest Visitor Guide

>>> >>> Inyo National Forest >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> Visitor Guide >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> $1.00 Suggested Donation FRED RICHTER Inspiring Destinations © Inyo National Forest Facts “Inyo” is a Paiute xtending 165 miles Bound ary Peak, South Si er ra, lakes and 1,100 miles of streams Indian word meaning along the California/ White Mountain, and Owens River that provide habitat for golden, ENevada border between Headwaters wildernesses. Devils brook, brown and rainbow trout. “Dwelling Place of Los Angeles and Reno, the Inyo Postpile Nation al Mon ument, Mam moth Mountain Ski Area National Forest, established May ad min is tered by the National Park becomes a sum mer destination for the Great Spirit.” 25, 1907, in cludes over two million Ser vice, is also located within the mountain bike en thu si asts as they acres of pris tine lakes, fragile Inyo Na tion al For est in the Reds ride the chal leng ing Ka mi ka ze Contents Trail from the top of the 11,053-foot mead ows, wind ing streams, rugged Mead ow area west of Mam moth Wildlife 2 Sierra Ne va da peaks and arid Great Lakes. In addition, the Inyo is home high Mam moth Moun tain or one of Basin moun tains. El e va tions range to the tallest peak in the low er 48 the many other trails that transect Wildflowers 3 from 3,900 to 14,494 feet, pro vid states, Mt. Whitney (14,494 feet) the front coun try of the forest. Wilderness 4-5 ing diverse habitats that sup port and is adjacent to the lowest point Sixty-five trailheads provide Regional Map - North 6 vegetation patterns ranging from in North America at Badwater in ac cess to over 1,200 miles of trail Mono Lake 7 semiarid deserts to high al pine Death Val ley Nation al Park (282 in the 1.2 million acres of wil der- meadows. -

LUGGAGE Sometimes a Little Added Storage Capacity Is Just What You Need to Make Your Ride More Enjoyable

LUGGAGE Sometimes a little added storage capacity is just what you need to make your ride more enjoyable. Rain gear, extra clothing and basic supplies are easy to take along when you add luggage to your bike. NOT ALL PRODUCTS ARE AVAILABLE IN ALL COUNTRIES - PLEASE CONSULT YOUR DEALER FOR DETAILS. 733 734 LUGGAGE ONYX PREMIUM LUGGAGE COLLECTION Designed by riders for riders, the Onyx Premium Luggage Collection is constructed from heavy-weight, UV-stable ballistic nylon that will protect your belongings from the elements while maintaining their shape and color so they look as good off the bike as on. SECURE MOLLE MOUNTING SYSTEM The versatile MOLLE (Modular Lightweight Load- Carrying Equipment) mounting system allows for modular pouch attachment. Slip-resistant bottom UV-RESISTANT FINISH keeps the bag in place on your bike. Solution-dyed during fabric production for long-life UV-resistance even when exposed to the sun's harshest rays. 2-YEAR HARLEY-DAVIDSON® WARRANTY REFLECTIVE TRIM Reflective trim adds an extra touch of visibility to other motorists. DURABLE BALLISTIC NYLON 1680 denier ballistic polyester material maintains its sturdy shape and protects your belongings for the long haul. LOCKING QUICK-RELEASE MOUNTING STRAPS Convenient straps simplify installation and removal and provide a secure no-shift fit. Not all products are available in all countries – please consult your dealer for details. ORANGE INTERIOR OVERSIZE HANDLES GLOVE-FRIENDLY ZIPPER PULLS INTEGRATED RAIN COVER Orange interior fabric makes it easy to Soft-touch ergonomic handle is shaped Ergonomically contoured rubberized Features elastic bungee cord with a see bag contents in almost any light. -

CORE STRENGTH WITHIN MONGOL DIASPORA COMMUNITIES Archaeological Evidence Places Early Stone Age Human Habitation in the Southern

CORE STRENGTH WITHIN MONGOL DIASPORA COMMUNITIES Archaeological evidence places early Stone Age human habitation in the southern Gobi between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago 1. While they were nomadic hunter-gatherers it is believed that they migrated to southern Asia, Australia, and America through Beringia 50,000 BP. This prehistoric migration played a major role in fundamental dispersion of world population. As human migration was an essential part of human evolution in prehistoric era the historical mass dispersions in Middle Age and Modern times brought a significant influence on political and socioeconomic progress throughout the world and the latter has been studied under the Theory of Diaspora. This article attempts to analyze Mongol Diaspora and its characteristics. The Middle Age-Mongol Diaspora started by the time of the Great Mongol Empire was expanding from present-day Poland in the west to Korea in the east and from Siberia in the north to the Gulf of Oman and Vietnam in the south. Mongols were scattered throughout the territory of the Great Empire, but the disproportionately small number of Mongol conquerors compared with the masses of subject peoples and the change in Mongol cultural patterns along with influence of foreign religions caused them to fell prey to alien cultures after the decline of the Empire. As a result, modern days Hazara communities in northeastern Afghanistan and a small group of Mohol/Mohgul in India, Daur, Dongxiang (Santa), Monguor or Chagaan Monggol, Yunnan Mongols, Sichuan Mongols, Sogwo Arig, Yugur and Bonan people in China are considered as descendants of Mongol soldiers, who obeyed their Khaan’s order to safeguard the conquered area and waited in exceptional loyalty. -

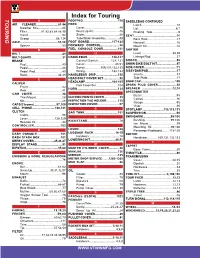

Index for Touring TOURING a FOOTPEG

Index for Touring TOURING A FOOTPEG...........................................125 SADDLEBAG CONTINUED AIR CLEANER...........................81-94 FORK Latch....................................10 Breather Kits..............................85 Cover........................................49 Lid..............................................6,7 Filter.................81,82,83,84,86,95 Dress Up Kit.................................46 Riveting Tool................................6 Insert.....................................92 Slider......................................48 SEAT.............................................16 Scoop.............................86,134 Tube/Slider Assembly..................48 Back Rest....................................17 AXLE..........................................55,56 FOOT BOARD............................117-124 Handrail......................................16 Spacer....................................55 FORWARD CONTROL.......................36 Mount Kit.....................................16 B FUEL CONSOLE DOOR..................101 SHIFTER BELT................................................41 H Lever.....................................38,39 BELT GUARD......................................31 HANDLEBAR.............................126-127 Linkage/Rod...............................37 BRAKE Control/Switch.............129,131 SHOCK........................................50 Pad........................................43 Cover..................................48,51 SHOW BIKE BOLT KIT........................97 Pedal........................................40 -

Toponymic Culture of China's Ethnic Minorities' Languages

E/CONF.94/CRP.24 7 June 2002 English only Eighth United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names Berlin, 27 August-5 September 2002 Item 9 (c) of the provisional agenda* National standardization: treatment of names in multilingual areas Toponymic culture of China’s ethnic minorities’ languages Submitted by China** * E/CONF.94/1. ** Prepared by Wang Jitong, General-Director, China Institute of Toponymy. 02-41902 (E) *0241902* E/CONF.94/CRP.24 Toponymic Culture of China’s Ethnic Minorities’ Languages Geographical names are fossil of history and culture. Many important meanings are contained in the geographical names of China’s Ethnic Minorities’ languages. I. The number and distribution of China’s Ethnic Minorities There are 55 minorities in China have been determined now. 53 of them have their own languages, which belong to 5 language families, but the Hui and the Man use Chinese (Han language). There are 29 nationalities’ languages belong to Sino-Tibetan family, including Zang, Menba, Zhuang, Bouyei, Dai, Dong, Mulam, Shui, Maonan, Li, Yi, Lisu, Naxi, Hani, Lahu, Jino, Bai, Jingpo, Derung, Qiang, Primi, Lhoba, Nu, Aching, Miao, Yao, She, Tujia and Gelao. These nationalities distribute mainly in west and center of Southern China. There are 17 minority nationalities’ languages belong to Altaic family, including Uygul, Kazak, Uzbek, Salar, Tatar, Yugur, Kirgiz, Mongol, Tu, Dongxiang, Baoan, Daur, Xibe, Hezhen, Oroqin, Ewenki and Chaoxian. These nationalities distribute mainly in west and east of Northern China. There are 3 minority nationalities’ languages belong to South- Asian family, including Va, Benglong and Blang. These nationalities distribute mainly in Southwest China’s Yunnan Province. -

Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Law, Language and Discourse

Proceedings of The Fifth International Conference on Law, Language and Discourse Sept. 27 – Oct. 1, 2015 Örebro University, Sweden The American Scholars Press Editors: Cheng Le, Laura Ervo, Jian Li, Lisa Hale and Jin Zhang Cover Designer: Xin Wang Published by The American Scholars Press, Inc. The Proceedings of The Fifth International Conference on Law, Language and Discourse is published by the American Scholars Press, Inc., Marietta, Georgia, USA. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Copyright © 2015 by the American Scholars Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-9861817-6-4 Printed in the United States of America 2 Preface Internationally, there is a growing interest from the academia and legal professionals in the study of the interface between language and law. Locally, Language and Law is one of the core postgraduate programs, which can be traced back to the early 1990s at City University of Hong Kong. In recent years, exchanges and collaborations in language and law between the City University of Hong Kong and other universities, including Aston University, China University of Political Science and Law, Columbia Law School, Georgetown University, and Peking University, have been frequent and productive. With Hong Kong, as an international city, playing an important role of the meeting point of different cultures and with China being the convergence of various jurisdictions, a new association – the Multicultural Association of Law and Language (hereafter, as MALL) was founded in 2009 with the Secretariat located in Hong Kong. -

Alexander Vovin 1 Curriculum Vitae for Alexander Vovin

Alexander Vovin Curriculum Vitae for Alexander Vovin ADDRESSES home address: work address: 1, rue de Jean-François Lépine EHESS-CRLAO 75018 Paris FRANCE 131, bd Saint-Michel 75005 Paris, FRANCE [email protected] [email protected] PERSONAL DATA Born 01/27/1961 in St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad), Russia US citizen, married (spouse: Sambi Ishisaki Vovin (石崎(ボビン)賛美), two children EDUCATION Leningrad State U. "Kandidat filologicheskikh nauk"(=Ph.D.) 10/29/87 Dissertation: The Language of the Japanese prose of the second half of the XI Century. 189 pp. In Russian. Leningrad State U. "Vysshee Obrazovanie" (=MA) June, 1983 Philological Faculty, Department of Structural and Applied Linguistics. Thesis: The Dictionary Bongo zōmyō (『梵語雑名』) as a Source for the Description of some Peculiarities of the Phonetics of Early 18th Century Japanese. 73 pp. In Russian. EMPLOYMENT 01/01/2014 Directeur d’études, linguistique historique du Japon et de l’Asie du Nord- present Est, EHESS/CRLAO, Paris, France 08/01/2003 - Professor of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Department of 01/10/2014 East Asian Languages and Literatures, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, USA 08/01/1997- Associate Professor of Japanese, Department of 07/31/2003 East Asian Languages and Literatures, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, USA 08/01/1995- Assistant Professor of Japanese, Department of 07/31/1997 East Asian Languages and Literatures, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, USA 08/01/1994- Assistant Professor of Japanese, Department of 07/31/1995 German, Russian, and East Asian Languages, Miami University, USA 9/1/1990 - Assistant Professor of Japanese Language & 06/30/1994 Linguistics, Department of Asian Languages & Cultures, University of Michigan, USA 1 Alexander Vovin 6/1/1990 - Visiting Lecturer in Japanese, Department of Asian Languages 8/31/1990 & Cultures, University of Michigan, USA 3/1/1989 - Junior Scientific Researcher, Far East Sector, May, 1990 Japanese Group, Inst. -

A Grammar of Bao'an Tu, a Mongolic Language Of

A GRAMMAR OF BAO’AN TU, A MONGOLIC LANGUAGE OF NORTHWEST CHINA by Robert Wayne Fried June 1, 2010 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Buffalo, State University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics UMI Number: 3407976 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3407976 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 Copyright by Robert Wayne Fried 2010 ii Acknowledgements I wish to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Matthew Dryer for his guidance and for his detailed comments on numerous drafts of this dissertation. I would also like to thank my committee members, Karin Michelson and Robert VanValin, Jr., for their patience, flexibility, and helpful feedback. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to be a part of the linguistics department at the University at Buffalo. I have benefited in ways too numerous to recount from my interactions with the UB linguistics faculty and with my fellow graduate students. I am also grateful for the tireless help of Carole Orsolitz, Jodi Reiner, and Sharon Sell, without whose help I could not have successfully navigated a study program spanning nine years and multiple international locations. -

Tibet Outside the TAR Page 2159

CFP-W, Chentsa Chinese: Jianza Xian Alliance for Research in Tibet (ART) Tibet Outside the TAR page 2159 roll/neg: 54:15 subject: wide angle view of the town location: Chentsa Dzong CFP-W-éE,, Malho -é, Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Tsongön UWê-¢éP, [Ch: Jianza , Huangnan TAP, Qinghai Province] approx. date: winter 1995/1996 comment: In the distance is the Machu (Huanghe, Yellow R.). Across the river is Haidong Prefecture with two million inhabitants, at least two thirds of them Chinese and Hui. Official population in Chentsa is about 49,000, with a 60% Tibetan majority claimed. The true Tibetan proportion is probably lower. Demographic pressure is intense: population density in Chentsa, the nearest to Xining and Haidong, is 28 persons/km2 . The next county, the capital, Regong, has 21. In Tsekhog it is 7 and only 4 in Yülgan. (Viewed from the south.) © 1997 Alliance for Research in Tibet (ART), all rights reserved Alliance for Research in Tibet (ART) Tibet Outside the TAR page 2161 b. Chentsa [Ch: Jianza] i. Brief description and impressions Chentsa CFP-W-éE, (Ch. Jianza Xian ) is one of the most vulnerable of all the Tibetan counties to patterns of development preferred by China. Only the Yellow River (Ma Chu), edging its northern border, now divides it from the densely-populated Chinese and Hui region of Haidong Prefecture. This geographical feature once served as a clear and formidable marker between a totally Tibetan world to the south and a region which, though sinicizing gradually over the centuries, did not overleap the Yellow River until the Communist Chinese occupation. -

1 Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I Have Been

Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I have been unconsciously entangled in a historical process of the making of modern Buddhism. There was a Chinese temple beside my house in Penang, Malaysia. The main deity was likely a deified imperial court officer, though no historical record documented his origin. A mosque serenely resided along the main street approximately 50 meters from my house. At the end of the street was a Hindu temple decorated with colorful statues. Less than five minutes’ walk from my house was a Buddhist association in a two-storey terrace. During my childhood, the Chinese temple was a playground. My friends and I respected the deities worshipped there but sometimes innocently stole sweets and fruits donated by worshippers as offerings. Each year, three major religious events were organized by the temple committee: the end of the first lunar month marked the spring celebration of a deity in the temple; the seventh lunar month was the Hungry Ghost Festival; and the eighth month honored, She Fu Da Ren, the temple deity’s birthday. The temple was busy throughout the year. Neighbors gathered there to chat about national politics and local gossip. The traditional Chinese temple was thus deeply rooted in the community. In terms of religious intimacy with different nearby temples, the Chinese temple ranked first, followed by the Hindu temple and finally, the mosque, which had a psychological distant demarcated by racial boundaries. I accompanied my mother several times to the Hindu temple. Once, I asked her why she prayed to a Hindu deity. -

Typological Interaction in the Qinghai Linguistic Complex

TYPOLOGICAL INTERACTION IN THE QINGHAI LINGUISTIC COMPLEX Juha Janhunen The Gansu or Hexi Corridor in the Upper Yellow River region forms the natural contact zone between four major cultural and linguistic realms: China þroper) in the east, Mongolia in the north, Turkestan in the west, and Tibet in the south. Populations and languages from these four regions have since ancient times penehated into Gansu, where they have been integrated into the local network of ethnolinguistic variation. In particular, the fragmentated landscape of the southem part of the region, historically known as the Amdo (Written TibetanxA.mdo)Pro- vince of Tibet and today mainly administered as the Qinghai Province of China, has recurrently provided a refuge for intrusive populations speaking a variety of different tongues. The greatest diversity of languages is found in a relatively small territory located to the east and north of Lake Qinghai, or Kuku Nor (Written Mongol Guiganaqhur), areas today known as Haidong and Haibei, respectively. A general characteristic of all the languages involved is that they have undergone rapid differentiation as compared with their genetic relatives spoken elsewhere. At the same time, they have developed conìmon features shared areally across genetic boundaries. Moreover, many of these common features are structurally so import- ant and typologically so idiosyncratic that it is well motivated to view them as manifestations of a single areal entity. This entity may be termed the Qinghai Linguistic Complex, or also the Qinghai Sprachbund. Other equally possible names include the Amdo Sprachbund, the Amdo Linguistic Region, or the Yellow River Plateau Language Union. Geographically it has to be noted that the Qinghai Linguistic Complex is not fully congruous with the borders of Qinghai Province, nor with those of the historical Amdo Province of Tibet.