Appendix: Machiavelli in Post-Stalin Russia, 1953–98

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Monita Secreta Or, As It Was Also Known As, The

James Bernauer, S.J. Boston College From European Anti-Jesuitism to German Anti-Jewishness: A Tale of Two Texts “Jews and Jesuits will move heaven and hell against you.” --Kurt Lüdecke, in conversation with Adolf Hitleri A Presentation at the Conference “Honoring Stanislaw Musial” Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland (March 5, 2009) The current intense debate about the significance of “political religion” as a mode of analyzing fascism leads us to the core of the crisis in understanding the Holocaust.ii Saul Friedländer has written of an “historian‟s paralysis” that “arises from the simultaneity and the interaction of entirely heterogeneous phenomena: messianic fanaticism and bureaucratic structures, pathological impulses and administrative decrees, archaic attitudes within an advanced industrial society.”iii Despite the conflicting voices in the discussion of political religion, the debate does acknowledge two relevant facts: the obvious intermingling in Nazism of religious and secular phenomena; secondly, the underestimated role exercised by Munich Catholicism in the early life of the Nazi party.iv My essay is an effort to illumine one thread in this complex territory of political religion and Nazism and my title conveys its hypotheses. First, that the centuries long polemic against the Roman Catholic religious order the Jesuits, namely, its fabrication of the Jesuit image as cynical corrupter of Christianity and European culture, provided an important template for the Nazi imagining of Jewry after its emancipation.v This claim will be exhibited in a consideration of two historically influential texts: the Monita 1 secreta which demonized the Jesuits and the Protocols of the Sages of Zion which diabolized the Jews.vi In the light of this examination, I shall claim that an intermingled rhetoric of Jesuit and Jewish wills to power operated in the imagination of some within the Nazi leadership, the most important of whom was Adolf Hitler himself. -

E Conspiracy Eory to Rule Em

8/23/2020 The Conspiracy Theory to Rule Them All - The Atlantic Give a Gift e Conspiracy eory to Rule em All What explains the strange, long life of e Protocols of the Elders of Zion? Tereza Zelenkova Story by Steven J. Zipperstein NONE SHADOWLAND Like The Atlantic? Subscribe to The Atlantic Daily, our free weekday email newsletter. Enter your email Sign up Photography by Tereza Zelenkova https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/1857/11/conspiracy-theory-rule-them-all/615550/?preview=TcuaT5ZaZmqDeMMyDONAXVilKqE 1/8 8/23/2020 The Conspiracy Theory to Rule Them All - The Atlantic is article is part of “Shadowland,” a project about conspiracy thinking in America. ’ most consequential conspiracy text entered the world barely noticed, when it appeared in a little-read Russian newspaper in T 1903. The message of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is straightforward, and terrifying: The rise of liberalism had provided Jews with the tools to destroy institutions—the nobility, the church, the sanctity of marriage—whole. Soon, they would take control of the world, as part of a revenge plot dating back to the ascendancy of Christendom. The text, ostensibly narrated by a Jewish leader, describes this plan in detail, relying on centuries-old anti-Jewish tropes, and including lengthy expositions on monetary, media, and electoral manipulation. It announces Jewry’s triumph as imminent: The world order will fall into the hands of a cunning elite, who have schemed forever and are now fated to rule until the end of time. It was a fabrication, and a clumsy one, largely copied from the obscure, French- language political satire Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu, or The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu, by Maurice Joly. -

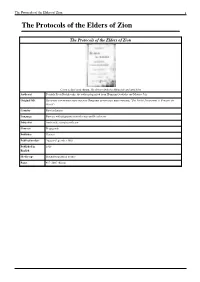

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion (Russian: "Протоколы сионских мудрецов" or "Сионские протоколы") is one of many titles given to an antisemitic text purporting to describe a plan to achieve global domination by the Jewish people. Following its first public publication in 1903 in the Russian Empire, a series of articles printed in The Times in 1921 revealed that much of the material was directly plagiarized from earlier works of political satire unrelated to Jews. [1] Publication history The Protocols appeared in print in the Russian Empire as early as 1903. The anti-Semitic tract was published in Znamya , a Black Hundreds newspaper owned by Pavel Krushevan, as a serialized set of articles. It appeared again in 1905 as a final chapter (Chapter XII) of a second edition of Velikoe v malom i antikhrist (The Great in the Small & Antichrist), a book by Serge Nilus. In 1906 it appeared in pamphlet form edited by G. Butmi. [1] These first three (and subsequently more) Russian language imprints were published and circulated in the Russian Empire during 1903–1906 period as a tool for scapegoating Jews, blamed by the monarchists for the defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and the 1905 Russian Revolution. Common to all three texts is the idea that Jews aim for world domination. Since The Protocols are presented as merely a document, the front matter and back matter are needed to explain its alleged origin. The diverse imprints, however, are mutually inconsistent. The general claim is that the document was stolen from a secret Jewish organization. -

Fhe Truth About U the Protocols"

Vf ; fhe Truth About u The Protocols" A LITERARY FORGERY From he Ctmes California jgional ,cility LONDON: PRINTING HOUSE SQUARE, E.C.4. ONE SHILLING NET. The Truth About "The Protocols" A LITERARY FORGERY From Cfje Cimeg of August 16, 17, and 18, 1921 LONDON: PRINTING HOUSE SQUARE, E.C.4. PREFACE. " The so-called Protocols of the Elders of " Sion were published in London in 1920 " under the title of The Jewish Peril." This book is a translation of a book pub- lished in Russia, in 1905, by Sergei Nilus, a Government official, who professed to have received from a friend a copy of a summary of the minutes of a secret meeting, held in Paris by a Jewish organization that was plotting to overthrow civilization in order to establish a Jewish world state. " " These Protocols attracted little atten- tion until after the Russian Revolution of 1917, when the appearance of the Bolshevists, among whom were many Jews professing and practising political doctrines that in some points resembled those advocated in " the Protocols," led many to believe that Nilus's alleged discovery was genuine. The " " Protocols were widely discussed and translated into several European languages. Their authenticity has been frequently at- tacked and many arguments have been adduced for the theory that they are a forgery. In the following three articles the Con- stantinople Correspondent of The Times presents for the first time conclusive proof that the document is in the main a clumsy plagiarism. He has forwarded to The Times a copy of the French book from which the A2 plagiarism is made. -

Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust

This page intentionally left blank P1: FpQ CY257/Brustein-FM 0 52177308 3 July 1, 2003 5:15 Roots of Hate On the eve of the Holocaust, antipathy toward Europe’s Jews reached epidemic proportions. Jews fleeing Nazi Germany’s increasingly anti- Semitic measures encountered closed doors everywhere they turned. Why had enmity toward European Jewry reached such extreme heights? How did the levels of anti-Semitism in the 1930s compare to those of earlier decades? Did anti-Semitism vary in content and intensity across societies? For example, were Germans more anti-Semitic than their European neighbors, and, if so, why? How does anti-Semitism differ from other forms of religious, racial, and ethnic prejudice? In pursuit of answers to these questions, William I. Brustein offers the first truly systematic comparative and empirical examination of anti-Semitism in Europe before the Holocaust. Brustein proposes that European anti-Semitism flowed from religious, racial, economic, and po- litical roots, which became enflamed by economic distress, rising Jewish immigration, and socialist success. To support his arguments, Brustein draws upon a careful and extensive examination of the annual volumes of the American Jewish Year Book and more than forty years of newspaper reportage from Europe’s major dailies. The findings of this informative book offer a fresh perspective on the roots of society’s longest hatred. William I. Brustein is Professor of Sociology, Political Science, and His- tory and the director of the University Center for International Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. His previous books include The Logic of Evil (1996) and The Social Origins of Political Regionalism (1988). -

288361069.Pdf

LOUGHBOROUGH UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY LIBRARY AUTHOR/FILING TITLE ---------- ----~~-~-~:.<='?~-.>--~- ------------ -------------------------------- -).- ---------·------ ' ACCESSION/COPY NO. '1 . I _!?_~-':\:~-~:1_\':?~---------- ------ VOL. NO. CLASS MARK ~~ .-1 Ovls91J ~·- / ------- -- -~------------------------------ - --- -~--~-~----------- ----, ANTI-SEMITIC JOURNALISM AND AUTHORSHIP IN BRITAIN 1914-21 by David Beeston A Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of the Loughborough University of Technology (December 1988) - --------------------- ~ DECLARATION This thesis is a record of research work carried out by the author in the Department of Economics of Loughborough University of Technology and represents the independent work of the author; the work of others has been referenced where appropriate. The author also certifies that neither this thesis nor the original work contained herein has been submitted to any other institutions for a degree. DAVID BEESTON ----------------------------------------------------------~ ABSTRACT ANTI-SEMITIC JOURNALISM AND AUTHORSHIP IN BRITAIN. 1914-21 by DAVID BEESTON This thesis illustrates how anti-semitism has found favour, comparatively recently, among influential sectors of the journalistic and literary establishment, and also how periods of intense national and international crisis can create the conditions in which conspiratorial explanations of major events will surface with relative ease. During the seven years following -

1. French Republican Philosophy of Science and Sorel’S Path to Marx

Georges Sorel, Autonomy and Violence in the Third Republic by Eric Wendeborn Brandom Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Malachi Haim Hacohen, Supervisor ___________________________ Roberto Dainotto ___________________________ Laurent M. Dubois ___________________________ Michael Hardt ___________________________ Christophe Prochasson ___________________________ William M. Reddy ___________________________ K. Steven Vincent Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 i v ABSTRACT Georges Sorel, Autonomy and Violence in the Third Republic by Eric Wendeborn Brandom Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Malachi Haim Hacohen, Supervisor ___________________________ Roberto Dainotto ___________________________ Laurent M. Dubois ___________________________ Michael Hardt ___________________________ Christophe Prochasson ___________________________ William M. Reddy ___________________________ K. Steven Vincent An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Eric Wendeborn Brandom 2012 Abstract How did Georges Sorel’s philosophy of violence emerge from the moderate, reformist, and liberal philosophy of the French Third Republic? This dissertation answers the question through a contextual intellectual history of Sorel’s writings from the 1880s until 1908. Drawing on a variety of archives and printed sources, this dissertation situates Sorel in terms of the intellectual field of the early Third Republic. I locate the roots of Sorel’s problematic at once in a broadly European late 19th century philosophy of science and in the liberal values and the political culture of the French 1870s. -

The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-516956-5

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion 1 The Protocols of the Elders of Zion The Protocols of the Elders of Zion Cover of first book edition, The Great within the Minuscule and Antichrist Author(s) Possibly Pyotr Rachkovsky; the author plagiarised from Hermann Goedsche and Maurice Joly Original title Програма завоевания мира евреями (Programa zavoevaniya mira evreyami, "The Jewish Programme to Conquer the World") Country Russian Empire Language Russian, with plagiarism from German and French texts Subject(s) Antisemitic conspiracy theory Genre(s) Propaganda Publisher Znamya Publication date August–September 1903 Published in 1919 English Media type Fraudulent political treatise Pages 417 (1905 edition) The Protocols of the Elders of Zion 2 A reproduction of the 1905 Russian edition by Serge Nilus, appearing in Praemonitus Praemunitus (1920). Part of a series on Antisemitism Part of Jewish history • History • Timeline • Resources Category The Protocols of the Elders of Zion or The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion is an antisemitic hoax purporting to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. It was first published in Russia in 1903, translated into multiple languages, and disseminated internationally in the early part of the 20th century. Henry Ford funded printing of 500,000 copies that were distributed throughout the US in the 1920s. Adolf Hitler and the Nazis publicized the text as if it were a valid document, although it had already been exposed as fraudulent. After the Nazi Party came to power in 1933, it ordered the text to be studied in German classrooms. The historian Norman Cohn suggested that Hitler used the Protocols as his primary justification for initiating the Holocaust—his "warrant for genocide".[1] The Protocols purports to document the minutes of a late 19th-century meeting of Jewish leaders discussing their goal of global Jewish hegemony by subverting the morals of Gentiles, and by controlling the press and the world's economies. -

Waters Flowing Eastward

WATERS FLOWING EASTWARD The War Against the Kingship of Christ by L. FRY Edited and Revised by The Rev. Denis Fahey, C.S.S.P., B.A., D.Ph., D.D. (Professor of Philosophy and Church History) FLANDERS HALL PUBLISHING COMPANY P.O. Box 10726 New Orleans, LA. 70181 THE LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL THE REVEREND DENIS FAHEY, Afterward he brought me again unto the door of the house ; C.S.SP., D.D, and behold waters issued out under the threshold of the D.PH., M.A house eastward . Then said he unto me, These waters Editor of Waters issue out toward the east country, and go down into the Flowing Eastward desert, and go into the sea. EZEK. XLVII. 1, 8. It was in the 1950-5 that the Catholic theologian and writer, the Reverend Denis Fahey of Dublin offered to edit a new edition of Mrs. Fry's book. During his lifetime he was unable to allow his name to appear as its submission for Eccleiastial Censorship might have led to complications. The foreword and appendices and a number of notes to the present edition were the work of Father Fahey. The authoress, Mrs. L. Fry, was married to one of the aristocrats of Czarist Russia and she suffered harrowing experiences in the days of the Bolshevist Revolution. This first hand knowledge of Communism in action has given authority to her writings. For many years she was associated with the work of the late French priest Monseigneur Jouin, helping hime in his researches into the atheistic and Judeo-Bolshevist plot against Christianity. -

THE PROTOCOLS: Myth and History

THE PROTOCOLS: Myth and History ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B'NAI B'RITH This publication was prepared by Kenneth Jacobson, Director, Middle Eastern Affairs Department, Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith 1981 THE PROTOCOLS: MYTH AND HISTORY he document known as the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, said to be the secret plans of Jewish leaders for the attainment of Tworld domination, is, in fact, the most famous and vicious forgery of modern times. Though thoroughly discredited, the Protocols have succeeded time and time again in stirring up hatred and racism in the twentieth century. The document consists of 24 sections, each called a "Protocol," and professes to be the confidential minutes of a Jewish conclave con vened in the last years of the nineteenth century. This forged material places in the mouths of the "Jewish conspirators" a host of incredible statements and plans. Thus, for example, in the very first Protocol we see the Jews secretly subverting the morals of the Gentile world: "The peoples of the goyim [non-Jews] are bemused with alcoholic liquors; their youth has grown stupid on classicism and from early immorality, into which it has been inducted by our special agents — by tutors, lackeys, governesses in the houses of the wealthy, by clerks and others, by our women in the places of dissipation frequented by the goyim." The third Protocol tells of Jewish control of the world's gold supply and, with it, the world's economies: "We shall create by all the secret subterranean methods open to us and with the aid of gold, which is all in our hands, a universal economic crisis whereby we shall throw upon the streets whole mobs of workers simultaneously in all the countries of Europe." Plans for a World Government under a despotic Jewish King emerge from the fifth Protocol: "In the place of the rulers of today we shall set up a bogey which will be called the Super-Government Ad ministration. -

Protocols of Zion

THE PROTOCOLS OF ZION WITH PREFACE AND EXPLANATORY NOTES United We Stand, Divided We FalL The Protocols OF THE MEETINGS OF THE LEARNED ELDERS OF ZION WITH PREFACE AND EXPLANATORY NOTES Translated from the Russian Text by VICTOR E, MARSDEN Formerly Russian Correspondent of "The Morning Post" 1934 INDEX: PART I Page The Jewish Question—Pact or Fancy 7 Does a Definite Jewish World Program Exist? . _ 19 An Introduction to the Jewish Protocols 32 How the "Jewish Question"' Touches the Farm ......... 41 Dr. Levy, a Jew, Admits His People's Error 49 Jewish Idea of Central Bank for America 61 Jewish "Kol Nidre'* and "Eli, Eli" Explained 74 Judaism 86 PART n How the Protocols Came to Russia 9S How an American Edition was Suppressed 103 More Attempts at Refutation 118 Text and Commentary , . 136 PART III Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion . 142 Concluding Passage From the Epilogue of Nilus 227 A Few Illustrative Facts 229 Indepeiiden!: Order of B'Nai B'Rith—L O. B. B. 239 L'Alliance Israelite Universelle _ . _ 241 PART IV Fabianism 245 A 10- Year-Plan for .Socialists .257 Excerpts from Gongressman L. T. McFadden's Speech . .26^ The Organization on British Slavery 266 Conclusion 287 Appendix . , . 291 Victor E. Marsden. The author of this translation of the famous PROTOCOLS was himself a victim of the Revolution. He had lived for many years in Russia and was marri-ed to a Russian lady. Among his other activities in Russia he had been* for a number of years Russian Correspondent of the Morning Post, a position which he occupied when the Revolution broke out, and his vivid descriptions of events in Russia will still be in the recollection of many of the readers of that journal. -

EPIC of Survivat':

= .... lo'• - EPIC OF SURVIVAt': .. ' .' . Twenty-Fi¥,E:,:, . Centuries df' Anti -SemitisrIl~!i \ ,', )' c,"._ , ',: Samuel Glassman Bloch Publishing Company • New York I • ,_.,"""... _,...;,..1.< ...."''''>•• , {ntensijication of Jew-Hatred in Russia: I 281 ,,: < dishonest methods. Joly introduced the spirits .. .' philosophers engaged in calm discussion. One was the very ··2··············~···4·· Italian, Niccolo Machiavelli, who died in 1527. His writi~, became a guide for all the world's dictators, deal with the"pro how a ruler can maintain his power. William.I;.Qsnstein in Great Political Thinkers wrote: Jntensification of A ruler must try to make himself beloved of his SUbjects. necessary in order to keep his power. But if a ruler. is faced choice of being "good" and well-liked or offrightening and. .... Jew ..Hatred in Russia: his people, then the latter is a much better course of action, becal,l.Se is more effective. I .. ,. "",,'~J::- . "'I ',> ~ The Protocols According to Machiavelli, the greatest sin a.' ruler com~it;~i~I1qt I in being inhuman but in losing his power. Machiavelli's feUq:w .. , discussant is another famous philosopher. the French encyclop~di~J,<)/,~;! of the Elders of Zion Montesquieu, who died in 1755. Also a student of the pro~!e~s.:'ij associated with power, he believed that "power corrupts .... ~ul:fS:~·: , must not be given too much power. Of course, in order to goy,~rIl~!~:;:):1 As a result of the defeat inflicted upon Russia by Japan, and the I ruler does need a certain amount of power. bunhis po.wer fi\lJ~tl?t:b),.i?, upsurge ofrevolutionary unrest in the country, the Black Hundreds , controlled by law.